1 0 0 0 IR Gertrude Steinと「風景」

- 著者

- 三芳 康義

- 出版者

- 駒澤大学外国語部

- 雑誌

- 駒沢大学外国語部論集 (ISSN:03899837)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.47, pp.63-80, 1998-03

It is well known that Gertrude Stein's intelligent playfulness towards breaking the literary conventions that had been established traditional syntax and punctuation, led to a close relationship between literature and painting as she pursued creating her own style. Stein always claimed that Cezanne and, especially, Picasso had the greatest influence on her writing, saying that she was doing in writing what Picasso at the time was doing in painting. Stein's creative works-novels, prose poems, the body of short works called 'portraits,' and operas - were, as a result, products that mainly came from an aesthetic desire for abstraction. But when Stein expressed "landscape" in the real world, she put a special emphasis on 'realistic impressionism.' The purpose of this paper is to search for Stein's space of words, "anti-context," through the clue to "landscape" from especially 'The Good Anna' and 'Melanctha' in Three Lives (1909), Tender Buttons (1914), Lucy Church Amiably (1930) and Four Saints in Three Acts (1934). The style of 'The Good Anna' is a realistic expression of the American South's landscape on the model of Gustave Flaubert. But there is a clearly stylistic distinctiveness between 'The Good Anna' and 'Melanctha.' The former is typical of novel based on ninteenth century's realism while the latter indicates that Stein consciously began to make further simplification in words or phrases, and fragmentally represented bits of all things in landscape. Beginning with the prose poem, Tender Buttons, Stein consciously enhanced an eccentric tendency of the irrational combination of words and phrases. When we try to appreciate this poem by viewpoints of the conception of language as a rational means of conveying thought, the meanings of each word become very obscure and mostly meaningless. Stein's literary experimentations might be seen as washing off the dust from a language which accumulated with the stale usage of words in traditional conventions. As for Stein, the rose is not necessarily red. In a way, Tender Buttons represents the final stage of development towards abstraction in words. But Stein's attitude towards the fragmentation of words was delicately changed in the 1920's. A romantic novel, Lucy Church Amiably attains a lyrical beauty that had never appeared before in her writing, and which is compared in popular criticism to Greek romance, Daphne and Chloe. This pastoral novel demonstrates that Stein started to express rather realistically the objects such as the earth, the air, trees, birds and so forth. Unexpectedly, they appear as clearly impressionistic images which make up a part of "landscape" in the foundation of 'anti-context.' Finally, Stein wrote an anti-opera, Four Saints in Three Acts, where the characters, Saint Therese and Saint Ignatius are presented neither plot nor story. In one scene, Saint Ignatius sings a famous aria, "the pigeons on the grass alas and the magpie in the sky on the sky," that lays his heart bare as he becomes deeply moved to see the Holy Spirit, in particular, "magpie." The image of "magpie" is represented two-dimentionally in Stein's verbal landscape like Georgia O'Keeffe's painting titled A Blackbird with Snow-covered Red Hills (1946). What Stein did in this librette was not to recognize simply realistic "magpie" but to reorganize it into a purely formed design. As a result, this aria contains considerable beauty with which Stein revivified sacredly vital qualities of words, transforming them from merely secular cliches.

1 0 0 0 ガートルード・スタイン : 「戯曲」の始まり

- 著者

- 三芳 康義

- 出版者

- 城西大学

- 雑誌

- 城西人文研究 (ISSN:02872064)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.19, no.2, pp.59-80, 1992-01-25

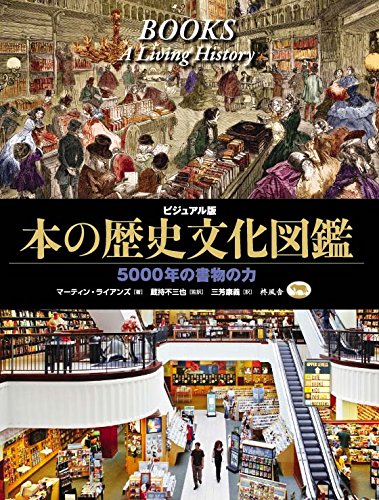

1 0 0 0 本の歴史文化図鑑 : ビジュアル版 : 5000年の書物の力

- 著者

- マーティン・ライアンズ著 三芳康義訳

- 出版者

- 柊風舎

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 2012