8 0 0 0 OA 近世陸奥中村藩における浄土真宗信徒移民の導入

- 著者

- 岩本 由輝

- 出版者

- 日本村落研究学会

- 雑誌

- 村落社会研究ジャーナル (ISSN:18824560)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.17, no.2, pp.18-29, 2011 (Released:2013-04-20)

- 参考文献数

- 13

Population decline, caused by increasing social mobility, and the related immigration of Hokuriku Jodo Shinshu-sect Buddhists were precipitated by the need to redevelop agriculture, reduce poverty and restore the Mutsu-Nakamura domain’s troubled finances in the latter part of the Tokugawa period. In the following paper, the memoranda of Kowata Hikobei (a rural administrator with the social position of samurai, who, along with his father, worked to organize the immigration) are used to explore the intelligence network by which 301 individuals from 57 households of the Jodo Shinshu religious community immigrated to the Mutsu-Nakamura domain during the period from 1815 to 1832. The arrival of some 3,000 or so immigrants in the Mutsu-Nakamura domain from 1813 to 1871 was seen as a great “success”, particularly in terms of re-invigorating the domain’s finances. It should be noted, however, that this internal migration neither assisted the contemporary strengthening of the shogunate nor hastened its collapse. Rather, having a strong intelligence network the Jodo Shinshu religious community removed itself from the framework of the shogunate, and in the process they served their own organization by, in effect, making the whole Japanese archipelago “borderless”.

3 0 0 0 OA 『栃木県史』史料編などにみる中世の遠野

- 著者

- 岩本 由輝

- 出版者

- 日本村落研究学会

- 雑誌

- 村落社会研究 (ISSN:13408240)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.8, no.2, pp.1-11, 2002 (Released:2013-08-10)

The name “Tono” was first recorded in 1334, one year after the collapse of the Kamakura Regime, just prior to the split of the royal dynasty into Northern and Southern courts in the so-called “Nanpoku-cho” period. At that time, an agent dispatched by the Asonuma clan, whose main fief was in Shimotsuke province, ruled the Tono fief of Mutsu province. According to historical materials from 1350, the Asonuma clan ruled the fiefs of seven provinces by dispatching various administrative agents, and by aligning themselves at first with Southern court, and then with the Northern court, in order to maintain control over their fiefs. Around 1382, however, the Asonuma clan were uprooted from their main fief in Shimotsuke province by the Oyama clan, and in that process the Asonuma clan moved to strengthen their position in Tono, becoming the Tono-Asonuma clan. Henceforth, the Tono-Asonuma clan maintained an effective control over Tono until the end of the 16th century. During 1600, however, with the creation of the Morioka fief by the Sannohe-Nanbu clan, and in accordance with the process of establishing daimyo throughout the Japanese archipelago, the Tono-Asonuma clan was banished from Tono and disappeared from the main stage of history.

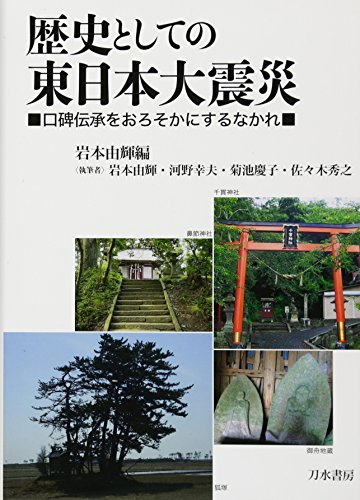

3 0 0 0 歴史としての東日本大震災 : 口碑伝承をおろそかにするなかれ

- 著者

- 岩本由輝編 岩本由輝 [ほか] 執筆

- 出版者

- 刀水書房

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 2013

1 0 0 0 本石米と仙台藩の経済

- 著者

- 岩本由輝著

- 出版者

- 大崎八幡宮仙台・江戸学実行委員会

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 2009