1 0 0 0 OA 龍眠会研究初探 ―彷徨する六朝書道をめぐって―

- 著者

- 中村 史朗

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2016, no.26, pp.31-44,117-116, 2016-10-30 (Released:2017-04-04)

As moves towards establishing institutional systems for art accelerated on the part of the administration during the Meiji 明治 era, calligraphy too underwent major changes. The realities of these changes were strikingly demonstrated by the emergence of the so-called Six Dynasties school of calligraphy. It is generally acknowledged that the Chinese scholar-collector Yang Shoujing 楊守敬 came to Japan with a large corpus of materials related to bronze and stone inscriptions, whereupon Kusakabe Meikaku 日下部鳴鶴 and other Japanese calligraphers who were stimulated by their contact with him established the new style of Six Dynasties calligraphy, sweeping away old calligraphic conventions. But this does not necessarily accord with actual developments thereafter. The new style of calligraphy proposed by Meikaku and others had a strong correlation with existing Tang-style calligraphy, and its character was such that it could be better referred to as “new Japanese-style calligraphy.” Subsequently the direction taken by Meikaku and others came to form the central axis of calligraphy during the Meiji era, but it was only natural that calligraphers and groups advocating a different orientation should have appeared, and the Six Dynasties school of calligraphy assumed a multilayered character. In this article, I first examine the actual substance of the Six Dynasties school of calligraphy as advocated by Meikaku and others, and then I undertake an examination of the activities of the Ryūminkai 龍眠会 (Society of the Slumbering Dragon) founded by Nakamura Fusetsu 中村不折 and others who lay at the opposite pole among the various parties espousing Six Dynasties calligraphy. Research into the history of Japanese calligraphy during the modern period has until now been primarily concerned with publicly recognizing outstanding calligraphers individually, and a stance that would clarify their relationships and trace historical developments has been wanting. In this article, I compare ideas of differing character that were put forward in relation to the Six Dynasties school of calligraphy while also ascertaining changes in calligraphy over time and the circumstances surrounding calligraphy with a view to making a start on forging links between past individual studies.

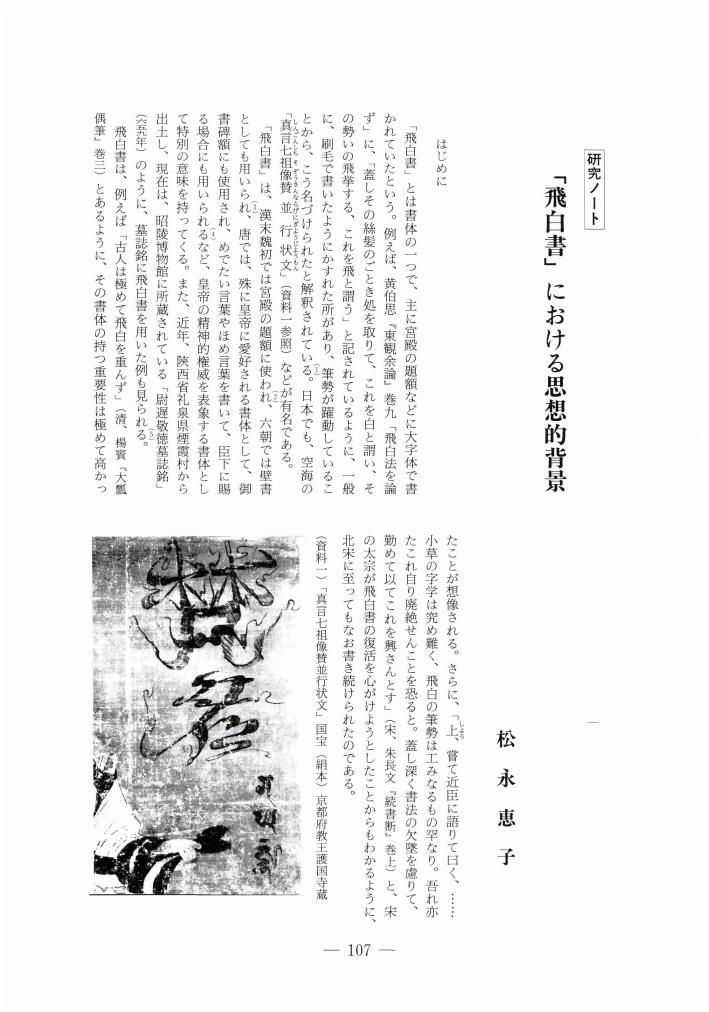

1 0 0 0 OA 「飛白書」における思想的背景

- 著者

- 松永 恵子

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.14, pp.107-121, 2004-09-30 (Released:2010-02-22)

1 0 0 0 OA 「扶桑再遊記」にみる羅振玉と日本人 ―社会的ネットワーク分析の視点から―

- 著者

- 菅野 智明 猿渡 康文

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2017, no.27, pp.1-16,83, 2017-11-30 (Released:2018-03-23)

The influx of vast quantities of Chinese painting and calligraphy following the 1911 Revolution has long attracted attention as an epoch-making event in terms of the history of artwork collections and the history of cultural intercourse. Luo Zhenyu 羅振玉 (1866-1940), who had moved to Kyoto to escape the upheavals of the Revolution, has been regarded as one of those who played a central role in this influx of Chinese painting and calligraphy into Japan, and he also deserves special mention in view of the fact that he took a lead in publishing photographic reproductions of these works. But prior to the Revolution Luo Zhenyu had made a tour of inspection of Japan in his capacity as an official of the Qing dynasty, and chiefly through his contacts with Japanese living in Tokyo who were well versed in Chinese culture he had managed to view various Chinese artefacts that had come to Japan, such as painting and calligraphy, stone and metal inscriptions, and books. Details of this are recorded in his diary, “Fusang zaiyouji” 扶桑再遊記 (1909). When analyzing the social network to be seen in this diary, the application of objective methods such as quantification becomes an issue. It would seem that it was the very structure of the network which was formed that had a greater influence on Luo Zhenyuʼs achievements during this visit to Japan than did the nature of his relations with individual Japanese with whom he came into contact. We consider the elucidation of this point to be also indispensable for gaining an understanding of his movements after he settled in Kyoto. In view of the above, in this article we apply the method of “social network analysis,” a quantitative method of analysis that has proven to be successful in the social sciences, with the aim of clarifying the structural characteristics of Luo Zhenyuʼs network of Japanese acquaintances to be seen in the “Fusang zaiyouji.” We also examine the possibility that the structure of this network may have had an influence on the achievements of his visit to Japan.

1 0 0 0 OA 初期羅振玉書画碑帖コレクションの日本への流入

- 著者

- 下田 章平

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2022, no.32, pp.57-70,128, 2022-10-31 (Released:2023-03-31)

In this paper, we mainly analyzed materials in the Naito Collection in Kansai University Library as part of Luo Zhenyu's research collection and examined the background of Luo Zhenyu's retreat to Kyoto to pursue his collection activities. We then further examined the Luo Zhenyu calligraphy, painting, and inscription rubbing collection (hereinafter the “Early Luo Zhenyu Collection”) and discussed the methods used to promote and sell them to Japanese collectors. As a result of the study, we found that Luo Zhenyu's decision to retreat to Kyoto was based on the arrangement by Fujita Kenpo, who determined that he would be able to raise the funds necessary to afford the expenses for the retreat and academic publishing. In fact, the initial cost of the Kyoto retreat was financed by the Uenobon Jushichijo. The sale of the Early Luo Zhenyu Collection also served to educate Japan about the reality of Ming and Qing calligraphy, paintings, and the good inscription rubbings and formed the core of the Ueno Yuchikusai and Onishi Kenzan collections. Yamamoto Jiho seemed to be inspired by such a movement and expanded the Ming and Qing calligraphy and paintings collection in a short period of time. Furthermore, the Luo Zhenyu collection was cataloged for sale in advance, and an exhibition of the collection was held. It should be noted that this later became a guideline for the collection group led by Inukai Bokudo in terms of methods of promotion and sale. In addition, we also found that Luo Zhenyu not only purchased the collection from Chinese collectors but also widely engaged in sales on their behalf and sales intermediation when the collection was transferred to the east. This suggests that a portion of the many calligraphy, paintings, and inscription rubbings released by the financially impoverished Qing imperial family and high-ranking officials flowed out through Luo Zhenyu to Japan, seeking a sales channel.

1 0 0 0 OA 何君閣道摩崖の書 ―四川省刻石に見る一形態―

- 著者

- 高澤 浩一

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2007, no.17, pp.13-28, 2007-09-30 (Released:2010-02-22)

1 0 0 0 OA 難波津の歌の享受史覚書 ―上代から『古今集』まで―

- 著者

- 安國 宏紀

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2009, no.19, pp.53-62, 2009 (Released:2012-02-29)

The Naniwazu 難波津 poem is known for the fact that it is associated with calligraphy practice in the kana 仮名 preface to the Kokinshu 古今集. But it is difficult to imagine that it was perceived as a poem for the practice of calligraphy from the time when it first began to be recited by people in ancient times. One needs to posit a process of reception, such that a poem which was originally unrelated to calligraphy practice was gradually associated with new functions as it gained acceptance, and then at a certain stage came to be understood in connection with the function of calligraphy practice. This article presents from such a viewpoint an overview of the reception and dissemination of the Naniwazu poem from ancient times to the Kokinshu. In Section 1, I first ascertain the fact that, judging from the repetition to be seen in its wording, the Naniwazu poem may be considered to have originally been a song from the district of Naniwa 難波. I also point out, again on the basis of its wording, that, by associating it with a ruler, it had the makings of a poem extolling his prosperity. Further, in view of the fact that "Naniwa" is used in connection with the emperor Kotoku 孝徳 and that importance was attached to Naniwa Palace and Naniwazu as centres of the reformist government centred on the emperor, I point out that the first ruler associated with the Naniwazu poem would have been Kotoku, and I suggest that the history of the reception of the Naniwazu poem began with its acceptance as a folk song, and during the reign of Kotoku it changed into a poem glorifying the emperor. In Section 2, I take up for consideration the attitude of obstructiveness towards Kotoku that is quite pronounced in the Man'yoshu 万葉集, and I argue that there is a strong possibility that from the late seventh century to the eighth century the Naniwazu poem was dissociated from Kotoku and came to be accepted by people in general. This dissociation of the Naniwazu poem from Kotoku may have added a degree of freedom to the poem's acceptance, resulting in the phenomenon of the multilinear coexistence of the Naniwazu poem with diverse functions, including calligraphy practice and wooden slips (mokkan 木簡) inscribed with poems, as can be seen in unearthed materials. I surmise that this multipurpose character of the Naniwazu poem is linked to the large quantity of unearthed materials from this period related to the Naniwazu poem. In Section 3, dealing with the references to the Naniwazu poem in the Kokinshu, its first recorded instantiation, I discuss as separate, independent materials relating to the reception of the Naniwazu poem the kana preface, which identifies it as a poem presented to the emperor Nintoku仁徳, the Chinese preface, which identifies it simply as a poem presented to an unnamed emperor, and an interpolated note, which views it as a poem that was composed by Wani 王仁 and presented to Nintoku. I conclude that the references to the Naniwazu poem in the Kokinshu have a multistratified structure in which there was superimposed on the Naniwazu poem's foundations of a poem extolling a ruler a connection with Nintoku by Ki no Tsurayuki 紀貫之, who was seeking to describe in the kana preface the ideals of waka 和歌 poetry, and a connection with Wani was further imposed by the interpolated note, which was based on the kana preface. In this article, I ascertain the character of the Naniwazu poem, which began as a song of the Naniwa district and, on the basis of its underlying potential to be associated with a ruler, developed in a multistratified manner as it formed connections with rulers such as the emperors Kotoku and Nintoku. At the same time, with regard to its functions, I show that the Naniwazu poem existed in a multilinear fashion, possessing a variety of functions that were not limited to the practice of calligraphy.

1 0 0 0 OA 〓石如の篆書に関する考察 ―李陽冰の影響を中心に―

- 著者

- 大迫 正一

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.14, pp.123-138, 2004-09-30 (Released:2010-02-22)

1 0 0 0 OA 庾肩吾『書品』攷 ―「天然」・「工夫」の淵源をめぐって―

- 著者

- 関 俊史

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2018, no.28, pp.1-14,104, 2018-10-31 (Released:2019-03-29)

Grading by “pin” was integrated in the form of “Xing san pin shuo” by the Dong Zhong shu school in the Han period, before being adopted by the government for employment and promotion under the name “Jiu pin zhong zheng System.” Since then, similar grading systems based on “pin” have been used in various fields, with the Shu pin by Yu Jian wu being one of the first among them. Several critical writings based on “pin” were subsequently published in rapid succession; extant studies have focused on the differences between Shu pin by Yu Jian wu and Shi pin by Zhong Rong. Shi pin by Zhong Rong explains that “qi” triggers the “xing qing” of a person into motion and encourages the person to sing and dance, evoking poetry. In other words, Shi pin argues that “qi” determines the grade of a text, a theory based on the chapter Yue ji of Li ji and Lun wen of Dian lun by Cao Pi. Shu pin introduces the grading ideas of “tian ran” and “gong fu” to determine “pin,” an approach that contrasts significantly with the Shi pin of Zhong Rong, who develops his theory around the idea of “qi.” Previous studies have indicated that the concepts of “tian ran” and “gong fu” were shaped by the influence of preceding theories of calligraphy. This article attempts to establish the origin of “tian ran” and “gong fu” in terms of character assessment. Furthermore, it redefines Shu pin as an activity of qing tan practiced throughout the six-dynasty period, and concludes that Yu Jian wu wrote Shu pin, influenced by qing tan.

1 0 0 0 OA 昭和初期における菊池惺堂の収蔵ネットワーク ―大橋廉堂先生入蜀画会を中心として―

- 著者

- 下田 章平

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2019, no.29, pp.73-87,103, 2019-10-31 (Released:2020-01-31)

This paper deals with Seido Kikuchi and Rendo Ohashi, who seem to have taken over the network of art collectors of Seido. I primarily examine Kikuchi Seido Nikki and some rare materials kept by the Ohashi family to reveal the network of Seido in the early Showa era. As a result of my examination, I conclude that Seido had a close relationship with the group of art collectors led by Bokudo Inukai in the early Showa era. In addition, I identify two important points that will help to reveal the bigger picture of the network of art collectors in the period from the Xinhai Revolution to the end of World War II, a transitional period in the history of art collection. First, the activities of collectors between Japan and China after Luo Zhenyu's return to China need to be researched. Second, the roles of the collectors in the network who were contemporaries of Seido Kikuchi (Senro Kawai, Rokkyo Sugitani, Sentaro Yamaoka, Kyozan Yamamoto, Hekido Tanabe, Ginjiro Fujiwara and Tatsujiro Hashimoto), as well as the roles of the collectors who led the next generation (Kikujiro Takashima, Yasunosuke Ogiwara and Tsuneichi Inoue) and of those in China (Choji Sasaki and Shunzaburo Kuroki), need to be considered. The network of Seido included many Japanese art collectors other than those mentioned above, but few points of contact between Chinese/Korean and Japanese art collectors, including their social relationships, have been confirmed; consequently, Chinese/Korean and Japanese art collectors are likely to have had separate networks. This fact will have to be taken into account when Chinese paintings, calligraphy and calligraphic rubbings are studied.

1 0 0 0 文字統一と秦漢の史書

- 著者

- 大西 克也

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2014, no.24, pp.93-103, 2014

1 0 0 0 OA 鋳物の技術と文字 —殷周金文の鋳造法をめぐって—

- 著者

- 山本 尭

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2020, no.30, pp.1-23,160, 2020-10-31 (Released:2021-03-16)

Despite a long history of research into the casting methods used for Jinwen in the Yin Zhou period—with a variety of hypotheses suggested to date—the actual methods used remained unclear. In light of this situation, the author has conducted multiple casting experiments with the cooperation of the Ashiyagamanosato Museum for the purpose of elucidating the casting methods used for Jinwen. This paper reports the results of the experiments and gives several preconsiderations against the background of changes in the lettering style used on Jinwen from the perspective of casting techniques. The results of our experiments conducted revealed that the so-called slip method, in which slip is applied repeatedly using a brush onto a plate buried in a core, most logically answers the questions about the casting methods used for Jinwen. Historically, this method was first suggested by RUAN Yuan of the Qing dynasty; in a sense, our experiments proved the validity of his suggestion after more than 200 years. Based on the success of our experiments in indicating the technical logicality of the burial method, the author also suggests that the casting method used for Jinwen introduced in this paper be named the “slip-plate method.” The experiment results do not rule out the possibility of other Jinwen casting methods. On the contrary, variations in technique are very likely depending on locations and time periods. During the Eastern Zhou period, some Jinwen letterings deviated from the typical Western Zhou style to show a significant proximity to the Zhuanshu style. These changes in lettering style suggest the historical background of changes in the casting method used from the slurry-plate to the model-carving method. Based on the above findings, further detailed examination of variations in Jinwen lettering styles is awaited in order to obtain detailed knowledge about the dissemination of the lettering culture during the Yin Zhou period along with the actual prevailing conditions. This will be an extremely important and significant research theme not only with respect to the history of the technique, but also for the histories of calligraphy and palaeography.

1 0 0 0 OA 中国古書論にみられる用筆理念の変遷 ―蔵鋒用筆を中心として―

- 著者

- 森 常雄

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1991, no.1, pp.103-124, 1991-06-30 (Released:2010-02-22)

1 0 0 0 OA 北大路魯山人と良寛書《縦読洹沙書》

- 著者

- 角田 勝久

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2018, no.28, pp.71-84,101, 2018-10-31 (Released:2019-03-29)

Ryokan (1758-1831), a Zen monk in the Edo period, is famous for his masterpieces such as “Hifumi, Iroha” and “Tenjotaifu.” However, his other large-scale work, “Judoku Goshasho” written on a large piece of paper (62.5 centimeters long and 329.4 centimeters wide) in large letters as high as 25 centimeters, remains relatively unknown. After its introduction in Ryokansama Meihinten published in 1963, “Judoku Goshasho” disappeared from all following collections of Ryokan works and exhibitions. However, once it was listed in Ryokan Ibokushu, published by Tankosha Publishing Co. Ltd. in 2015 and exhibited after an interval of half a century at the exhibition “Jiaino Hito Ryokan” held at Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art in September the same year, the work attracted wide attention. “Judoku Goshasho” is also noticeable as it was obtained by an artist Rosanjin Kitaokoji (1883-1959) in 1938, who, inspired by the work, completed “Ryokan Shibyobu” written in large kaisho letters in 1941. Against the traditional view that Rosanjin was deeply attached to Ryokan around 1938, reviews of Rosanjinʼs works listed in his collections of works revealed that he was already interested in Ryokan before 1927. After drawing a series of works which show his obsession to Ryokan, however, Rosanjin freed himself from the influence of calligraphies by Ryokan and completed “Iroha Byobu” with his original style in 1953 at the age of 70. This article concludes that Rosanjin’s “Iroha Byobu” is a result of close and detailed study of Ryokanʼs “Judoku Goshasho” by his side.

1 0 0 0 OA 偽刻家Xの形影 ―同手の偽刻北魏洛陽墓誌群―

- 著者

- 澤田 雅弘

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2005, no.15, pp.3-21, 2005-09-30 (Released:2010-02-22)

1 0 0 0 OA 明清時代の「顔真卿」 ―宋元時代の評価などとの比較を中心に―

- 著者

- 宮崎 洋一

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2017, no.27, pp.15-28,86-85, 2017-11-30 (Released:2018-03-23)

I have been examining Yan Zhenqing 顔真卿 of the Tang from the perspective of the reception of works of calligraphy in later times, and in my article “Sō-Gen jidai no ʻGan Shinkeiʼ” 宋元時代の「顔真卿」(“ʻYan Zhenqingʼ in the Song-Yuan period”; in Kokusai shogaku kenkyū / 2000 国際書学研究/2000, Tokyo: Kayahara Shobō 萱原書房, 2000), focusing on the Song-Yuan period, I examined accounts of Yan Zhenqing in abridged histories, his ancestral temple (Yan Lu Gong ci 顔魯公祠 ), his calligraphic works recorded in historical sources, and their assessment. In this article, I take up the assessment of his works, focusing in particular on the three phrases “silkworm heads and swallow tails” (cantou yanwei 蚕頭燕尾), “sinews of Yan, bones of Liu,” and zhuanzhou 篆籀 (seal script), and adding some new materials, I reexamine their usage during the Song and consider their dissemination and changes in their usage from the Ming period onwards. As a result, I clarify the following points. (1) Usage of the expression “silkworm heads and swallow tails” to describe the characteristics of Yan Zhenqingʼs calligraphy appears from the Northern Song, although this characterization was rejected in contemporary treatises on calligraphy; from the Ming period onwards it came to be used to describe the distinguishing features of the style of calligraphy in which he excelled, and in addition there are examples of its use from the Song period to comment on his clerical script (lishu 隷書). (2) The phrase “sinews of Yan, bones of Liu” referred to the calligraphic skills of Yan Zhenqing and Liu Gongquan 柳公権 and was not an assessment of Yan Zhenqingʼs calligraphy; although some instances of “sinews” being linked to Yan Zhenqingʼs calligraphy appear from the Southern Song and extend to the Ming, they are few in number, and examples of the use of this phrase in its initial meaning are also found from the Ming period onwards. (3) There are examples of the use of the term zhuanzhou in the Song, but it is questionable whether it was used in its present-day sense of explaining the provenance of Yan Zhenqingʼs calligraphy; examples of its use in its current meaning appear in the Yuan period and increase from the Ming period onwards. In addition, I point out that background factors in these changes in the usage of these terms and their entrenchment may have been the existence of the Yanshi jiamiao bei 顔氏家廟碑 and other works in regular script, references to which increase rapidly from the Ming period onwards, and the fact that there were few Song rubbings of Yan Zhenqingʼs works that might serve as benchmarks and people were seeing many rubbings from the Ming period onwards.

1 0 0 0 小島成斎の用印

- 著者

- 田村 南海子

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2012, no.22, pp.81-94, 2012

Kojima Seisai 小島成齋 (1796-1862) is referred to as one of the four great calligraphers of the <i>bakumatsu</i> 幕末 period, but there is much about his calligraphy and achievements that remains unclear. I have been conducting research on his works of calligraphy and his views on calligraphy, and in this article I focus on his signatures and seals added to completed works and the manner in which they were applied as part of an investigation into his calligraphic works.<br> First, I take up thirty-seven dated calligraphic specimens among publications and inscriptions and forty-two dated works bearing seals, and I carefully investigate the seal impressions of thirty-one seals used by Seisai, their wording and measurements, and the frequency with which they were used. I further undertook examinations of seals that were used especially frequently, and I determined that seals bearing his surname, his given name Chikanaga 親長, and his literary name Shisho 子祥 (島, 親長, 島親長, 子祥氏) may be considered to have been used from the age of seventeen to his early twenties when he was studying under Ichikawa Beian 市河米庵 (1779-1858); the seal 庫司馬印 is a seal carved in imitation of the <i>Qianziwen</i> 千字文 in cursive script by Huaisu 懷素 and may be supposed to have been used during his fifties; and the seals 源氏子節 and 源知足章 may be regarded as representative seals of his later years in view of the fact that both of these seals have been affixed to works mounted on hanging scrolls dating from when he was sixty-seven. Since there also exist forgeries of these last two seals, I point out that works attributed to Seisai may include forgeries, but the elucidation of further details will be a task for the future.<br> Next, I examined a distinctive method of affixing seals used by Seisai, namely, that of first writing his name or literary name and then affixing his seal on top of it. In view of the fact that similar examples can be found in the works of the Song-period Ouyang Xiu 歐陽脩, Su Dongpo 蘇東坡, Huang Tingjian 黄庭堅, and Mi Fu 米〓 and in Japanese works of calligraphy, I infer that Seisai followed this method because he regarded it as a traditional style of affixing seals. This can be understood as an example of his basing himself on revivalist thought and taking the Chinese classics as his norm in seals and methods of affixing seals too, just as he did in works of calligraphy in which he followed classical works. I believe that this examination of Seisai's use of seals will be useful for inferring the dates of his undated works too.

1 0 0 0 OA 日本書論史序説

- 著者

- 永由 徳夫

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2018, no.28, pp.29-42,103, 2018-10-31 (Released:2019-03-29)

This article tries to construct “A History of Japanese calligraphic theories.” When observed from the perspective of the history of calligraphic theories, calligraphic theories in Japan have three distinctive periods: “budding of calligraphic theories” in the early Heian period, “establishment of the theory of Jubokudo” from the late Heian to the Nanbokucho periods, and “prosperity of the theory of Karayo” in the Edo period. In the process of writing the article titled “An Introduction to the History of Japanese Calligraphic Theories” based on these three periods, the following three themes were identified:1. Systematization of calligraphic theories in the Mid-Ancient/Middle ages centered on the theory by the Sesonji family2. Relevance between calligraphic theories in the Mid-Ancient/Middle ages and those in the Early-Modern age3. Relationship between the theories of Wayo and Karayo in the Early-Modern age This article addresses the first theme—systematization of calligraphic theories in the Mid-Ancient/Middle ages centered on the theory by the Sesonji family. Focusing on Yakaku Shosatsusho written by the 8th head of the Sesonji family Yukiyoshi Fujiwara and its supposed source text Yakaku Teikinsho written by Koreyuki Fujiwara, the 6th head of the family, this article discusses the differences between the two texts and illustrates the nature of Yakaku Shosatsusho as a plainer version of the calligraphic theory by the Sesonji family. In contrast, Shinteisho by Tsunetomo Fujiwara or the 9th head of the family, remained a mere list of formalities and old practices, revealing the situation that the familyʼs calligraphic theory had fallen into formalization. It is inferred that the stereotypical view of Japanese calligraphic theories such as “humble books of hijisodens preaching family calligraphy with a list of formalities and old practices” originates mainly from their emasculation following Shinteisho. The author intends to continue dealing with other themes such as the relevance between calligraphic theories in the Mid-Ancient/Middle ages and those in the Early-Modern age, as well as relationship between the theories of Wayo and Karayo in the Early-Modern age, to complete “A History of Japanese calligraphic theories” from the perspective of “Identifying the aesthetics of the Japanese people.”

- 著者

- 柳田 さやか

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2015, no.25, pp.109-123,175, 2015

As part of an inquiry into changes in the modern concept of "art," in this article I examine the scope of "art" and the position of calligraphy in the Ryūchikai 龍池會, which was founded in 1879 as the first Japanese art association (and was later renamed Japan Art Association). Prompted by the Ryūchikai's treatment of calligraphy as art, in 1882 Koyama Shōtarō 小山正太郎 published an essay entitled "Calligraphy Is Not Art" ("Sho wa bijutsu narazu" 書ハ美術ナラス). But following a careful examination of the official organs of the Ryūchikai and Japan Art Association, it has become clear that already prior to the publication of this essay there were differences of opinion among members of the Ryūchikai about whether or not to include calligraphy in "art." Furthermore, while a small number of early pieces of calligraphy were exhibited as examples of old works in exhibitions sponsored by the Ryūchikai and Japan Art Association, no requests were made for exhibits of new pieces of calligraphy, and it was confirmed that in effect there was a strong tendency to exclude calligraphy from "art." <br> In response to this state of affairs, calligraphers led by Watanabe Saō 渡邊沙鷗 established the Rikusho Kyōkai 六書協會 within the Japan Art Association with the aim of having calligraphy treated in the same way as painting. But the Japan Art Association instructed them to disband four years later, and so the calligraphers decided to resign from the Japan Art Association. The following year they established their own Japan Calligraphy Association and actively campaigned to have calligraphy exhibited at art exhibitions sponsored by the Ministry of Education and at other exhibitions and expositions. The Rikusho Kyōkai merits renewed attention as a pioneering group that aspired to have calligraphy recognized as a form of "art" and held exhibitions of only calligraphy on a continuing basis.

1 0 0 0 OA 三井本十七帖考

- 著者

- 澤田 雅弘

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2017, no.27, pp.1-14,86, 2017-11-30 (Released:2018-03-23)

It can be inferred at first sight that there is a close relationship between the version of the Shiqi tie 十七帖 held by the Art Museum of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (hereafter Hong Kong version) and the Mitsui 三井 version, but there is no generally accepted theory about the relationship between these two versions. Wang Zhuanghong 王壮弘 has asserted that the Mitsui version is a reproduction of the Hong Kong version, while Wang Yuchi 王玉池 considers both to have been produced from the same woodblocks, with the Mitsui version having further “developed” the characteristics of lifting the brush between strokes (duanbi 断筆) and regularity of brush strokes. He Biqi 何碧琪 also considers both to have been produced from the same woodblocks and suggests that the differences between them arose because the Mitsui version was “retouched” or “re-inked.” The main new findings obtained through the investigations described in this articles are as follows. (1) In view of the fact that not only do the scratches and cracks coincide in both versions, but the grooves of the carved strokes that happen to have been preserved in the rubbings also tally, it is obvious that both were produced from the same woodblocks, and the view that the Mitsui version is a reproduction of the Hong Kong version is wrong. (2) Some of the reasons for the differences that have arisen between the strokes in both versions lie in each version, but most of the differences are due to the ink and whitewash that were applied to the Hong Kong version. (3) The lifting of the brush between strokes, which stands out in the Mitsui version, is all the more noticeable because of measures taken to reduce it in the Hong Kong version, and claims by Chinese scholars that the Mitsui version has marred the intent of the original woodblocks are untenable. (4) Among Japanese scholars it has been argued that, while the lifting of the brush between strokes in the Mitsui version is unnatural, it was deliberately trace-copied to clarify the brushwork or else is a reflection of the intent of the original woodblocks, but this is a misconception based on a dearth of information about the Ueno 上野 version with which the Mitsui version has been compared, and the lifting of the brush between strokes can be widely seen in other versions too, notwithstanding differences of degree and frequency, and is by no means a reflection of aims peculiar to the Mitsui version. (5) The lifting of the brush between strokes is a technique that can be seen already around the time of the Western Jin, and since it may be considered to represent one aspect of Wang Xizhi's 王羲之 universal calligraphic techniques, the lifting of the brush between strokes in the Mitsui version preserves to a high degree the state of the original woodblocks and one aspect of Wang Xizhi's calligraphy.

1 0 0 0 OA 董其昌の歴代法帖に対する見解について

- 著者

- 大鹿 まゆみ

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2008, no.18, pp.61-71, 2008-09-30 (Released:2010-02-22)