4 0 0 0 OA 方言調査法の方法論的検討-方言調査データの信頼性の測定-

同一のインフォーマントに同じ方言調査を繰り返し実施した場合,その調査結果はどの程度安定するのだろうか。本研究は方言調査データの「信頼性」(調査データがどの程度安定するのか)を明らかにすることを目的とする。宮城県角田市と伊具郡丸森町および福島県田村郡小野町において実験的調査を実施し,方言調査データの信頼性を把握した。伊具地方の調査では,多くの項目の安定性(2回の調査の一致度)は80%程度との結果が得られた。他のデータについても今後も分析を進め,結果を公表する予定である。

1 0 0 0 OA ある方言地図の解釈

- 著者

- 加藤 正信

- 出版者

- The Linguistic Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1962, no.42, pp.31-46, 1962-10-31 (Released:2010-11-26)

As an experiment in linguistc geography, the writer takes up in the present paper the distribution of a variety of forms denoting salix caprea in the Island of Sado. This word may not belong to the basic Japanes vocabulary, nor can its variation constitute such an important dialectological feature as the word for “bought”, which divides Japan into two areas, one (east) with the form katta and the other (west) with the form kota. Even the conclusion about the changes the word has undergone in that island may have little significance in itself. The writer's aim here is to present the procedures that have led him to his conclusion and invite critical comments from his colleagues.In actual field work, the writer was assisted by Mrs. Sadako Kato. They visited almost all the communities (160 communities in all) in the island except the northern region, from 1959 to 1962. In each community, they examined one informent, who was native to the community and born in the Meiji Era i. e. before 1912. As a result of the survey, 34 different forms have been recorded. If we represent these forms on the maps as they are, their distribution would look so complicated that it would be impossible to know where to draw a dividing line. Matters can be made much simpler, however, by classifying our forms into two groups, one containing the element inu ‘dog’ and one containing the element neko ‘cat’. Thus we find the ‘dog’ group distributed in the central part, and the ‘cat’ group along the seacoast.With respect to the history of the island, we know that it was the central part that was prosperous untill the sixteenth century, and, only later, important lines of communications developed along the coast. On the other hand, the ‘dog’ group contains certain forms affected by a law of vocalic change that must have been completed in the seventeenth or eighteenth century. These two considerations have led the writer to the conclusion that the ‘dog’ group belong to an older layer than the ‘cat’ group. If so, how did some forms of the ‘dog’ group come to be replaced by those of the ‘cat’ group? In order to answer this question, the writer reconstructs an approximate process of innovation on the basis of further material provided by his map, and considers factors involved in each case.

- 著者

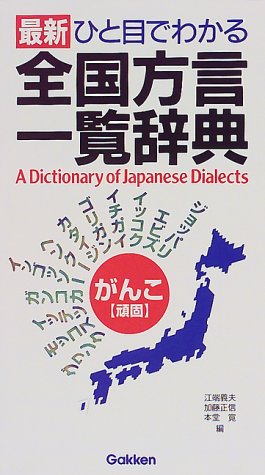

- 江端義夫 加藤正信 本堂寛編

- 出版者

- 学習研究社

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 1998