- 著者

- 山添 博史

- 出版者

- 国際安全保障学会

- 雑誌

- 国際安全保障 (ISSN:13467573)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.39, no.1, pp.12-27, 2011-06-30 (Released:2022-04-14)

- 著者

- ⼭添 博史

- 出版者

- ロシア・東欧学会

- 雑誌

- ロシア・東欧研究 (ISSN:13486497)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2020, no.49, pp.182-185, 2020 (Released:2021-06-12)

- 著者

- 山添 博史

- 出版者

- ロシア・東欧学会

- 雑誌

- ロシア・東欧研究 (ISSN:13486497)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2017, no.46, pp.129-131, 2017 (Released:2019-02-01)

- 著者

- 山添 博史

- 出版者

- ロシア・東欧学会

- 雑誌

- ロシア・東欧研究 (ISSN:13486497)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2014, no.43, pp.185-187, 2014 (Released:2016-09-09)

1 0 0 0 OA ロシアの安全保障分野における対中関係 ―リスク回避と実益の追求―

- 著者

- 山添 博史

- 出版者

- ロシア・東欧学会

- 雑誌

- ロシア・東欧研究 (ISSN:13486497)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2011, no.40, pp.79-90, 2011 (Released:2013-05-31)

- 参考文献数

- 46

The aim of this article is to provide an analysis of the nature of Russia’s security issues with China by focusing on two areas. Firstly, the study will see examples from Russia’s bilateral security relationship with China. Secondly, the analysis will subsequently provide an overview of the countries’ wider global interests. Resultantly, the article hopes to show that there exists no governing principle per se in Moscow’s relationship with Beijing but rather a cautious case-by-case approach. Reconciliation over border demarcation, an issue that spilled over into the actual conflict in 1969, has been critical in assuaging security relations between Moscow and Beijing. In their settlements of 1997 and 2004, both China and Russia made significant concessions on this issue despite fierce opposition within each country. This negotiation process was combined with the development of their relationship from reconciliation towards “strategic partnership.” However, Moscow’s efforts were driven by a longstanding desire to remove unstable elements on the border rather than an actual aspiration for greater security cooperation. Furthermore, Russian arms sales to China were a significant factor in their relationship and did reinforce China’s modern military capabilities especially towards the sea. However, arms trade has declined since 2007, largely due to the changing interests of Russian manufacturers and the Chinese equipment program. An export of RD-93 engines to China was suspended following the claim from a military industry executive that such components would be used in the construction of FC-1 fighters, a major export competitor to Russia’s own MiG-29. A dichotomy therefore exists in Russia between those seeking export income and those who wish to keep Chinese military capability below their own. Interestingly, Russian exports to India, a potential rival to China, are not so constrained. The first joint military exercise between China and Russia called “Peace Mission 2005” involved thousands of troops and was partly driven by a desire to show power and solidarity. Yet recent military exercises correspond to each country’s practical needs. In the “Peace Mission 2010” joint exercise, China for example focused on long-range flight capabilities. Russia meanwhile devotes more time and resources to joint exercises with former Soviet partners within the Collective Security Treaty Organization than it does with China. Finally, China and Russia share resistance to Western humanitarian intervention and pressure for democracy yet both countries found it hard to coordinate their opposition efforts in the 1990s due to varying interests. In the late 2000s each of Russia and China increasingly conducted independent foreign policies, confident in their increased international influence. But whilst common interests make both countries take similar approaches, coordination between them remains scant. In conclusion, the progress of each security issue depends on practical situations related to it rather than an overarching concept between Beijing and Moscow, such as that which used to determine relations during the Cold War. Whilst both share common non-interventionist policies, these are more often sought independently rather than cooperatively. In essence, a deeply embedded fear of China makes Russian bilateral policy cautious, eager not to turn China into a security concern.

- 著者

- 山添 博史

- 出版者

- The Japanese Association for Russian and East European Studies

- 雑誌

- ロシア・東欧研究 (ISSN:13486497)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2009, no.38, pp.104-106, 2009 (Released:2011-10-14)

- 被引用文献数

- 2 4

- 著者

- 山添 博史

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2021, no.203, pp.203_110-203_125, 2021-03-30 (Released:2022-03-31)

- 参考文献数

- 52

Russia, perceiving the U.S. political actions in Eastern Europe as threats to its vital interests there, developed the concept of ‘Strategic Deterrence.’ According to Russia’s ‘Military Doctrine’ of 2014, this concept means countering non-military and military threats to Russia’s interests by non-military, conventional, and nuclear means. Nuclear weapons can serve three purposes within this concept: ultimate means, conflict localization means, and narrative offensive means. Russia officially shows its readiness to use strategic nuclear forces as ultimate means to counter conventional threats to the existence of the state, and to develop conventional forces for local conflicts. When Russian officials mention the use of nuclear weapons, it serves as a narrative offensive means, which they expect will incite fear among the adversaries’ populations and weaken their united will to confront Russia, and thus fulfill the role of a non-military means of the ‘Strategic Deterrence’ framework. Russian military might think of what I call ‘conflict localization means’ in this paper, popularly known as an ‘escalate to de-escalate’ doctrine, a posture of using nuclear weapons to persuade adversaries to cease further military actions in a local conflict. ‘Military Doctrine’ of 2014 and other factors show little evidence of the existence of such a posture, but do not necessarily exclude the possibility. Partly to enhance a nuclear ‘narrative offensive,’ the possibility of use of nuclear weapons as a conflict localization means is made deliberately ambiguous. The Russian military did officially seek to realize the conflict localization means in the 2003 reform document, and debates on this matter continue. The ‘Grom-2019’ military exercise in October 2019 showed a possibility of forming a unified command and control not only of strategic nuclear forces but also of local-level weapons such as Kalibr and Iskander cruise missile systems with nuclear warheads. The issues of the nuclear threshold and strategic stability will depend on further development of forces and doctrines of Russia and the United States.

1 0 0 0 OA 「ポスト・プーチンのロシアの展望」(平成30年度 ロシア研究会)

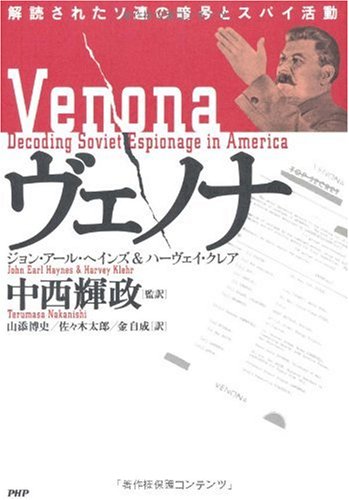

1 0 0 0 ヴェノナ : 解読されたソ連の暗号とスパイ活動

- 著者

- ジョン・アール・ヘインズ & ハーヴェイ・クレア [著] 山添博史 佐々木太郎 金自成訳

- 出版者

- PHP研究所

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 2010

- 著者

- 山添 博史

- 出版者

- JAPAN ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.139, pp.13-28,L6, 2004

This paper will examine Russo-Japanese diplomacy in the late 18th and the mid 19th centuries in order to understand the Japanese view of international order before being assimilated into the western international order.<br>As the Russians were approaching Ezo, now the northern islands of Japan, the Japanese recognised that Russia might capture Ezo and insisted on protecting it, whether the method was by trade with Russia or naval defence. Russia was an object to be examined as a counterpart, not an inferior barbarian under hierarchy in 'the Chinese World Order.' Matsudaira Sadanobu, the chancellor in 1787-93, regarded foreign countries as equal to Japan, and maintained that idea in order to understand them as potential enemies against Japan. When Russian envoy Laxman arrived at Ezo in 1792, Sadanobu dealt with his demand for direct communication to Edo and commerce, according to "politeness and rules", at the same time leading him to Nagasaki, which could avoid a Russian intrigue against Japan, and preparing the defence. Sadanobu paid attention to the potential threat posed by Russia and other states, coping with that threat by satisfying them and rejecting them according to law, as a means both practical and moral. In the Japanese view of international order, hierarchy was not a basis in the sense that Japan ruled the surrounding order. Rather nations were equal and tended to expand without moral constraints. In Sadanobu's case, the common language was politeness and rules, and the Chinese order and Western order were also recognised as separate international systems in the same world. In this sense, the Japanese view of international order was already "modernised" in advance of intense interactions with the West, and also had developed as a unique one of the Japanese origin.<br>Reflecting the appearance of western ships and the Opium War, the Japanese recognised that the Western threat was strong enough to assimilate China and Japan. This threat intensified the emphasis on competitive aspects of the Japanese view of international order, thus splitting sharply arguments for trade and those for exclusion. Even in views of <i>Jo-i</i> exclusionists, the international order consisted not of hierarchy with Japan on the top, but of warring equal states. Kawaji Toshiakira, negotiating the border with the Russian envoy Putiatin in 1853, also regarded European states as equal enemies to be studied in order to oppose. In his view of international order, though the evil intentions of European states were emphasised in comparison with the views in the 18th century, the "modernised" aspects such as equality among nations and rational thinking without moral restraints were inherited.