2 0 0 0 OA 章草の名義をめぐる一試論

- 著者

- 山元 宣宏

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2008, no.18, pp.87-102, 2008-09-30 (Released:2010-02-22)

- 著者

- 青山 由起子

- 出版者

- ASSOCIATION FOR CALLIGRAPHIC STUDIES

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.15, pp.71-87, 2005

2 0 0 0 近衛本『和漢朗詠集』の性格:粘葉本系統との関係を中心に

- 著者

- 山本 まり子

- 出版者

- ASSOCIATION FOR CALLIGRAPHIC STUDIES

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2014, no.24, pp.29-41,118, 2014

Previous studies on the text of the Konoe 近衛 manuscript of the <i>Wakan rōeishū</i> 和漢朗詠集 have been published by Horibe Shōji 堀部正二 and Katagiri Yōichi 片桐洋一. Horibe argued that the Konoe manuscript and the Detchōbon 粘葉本, Iyo-gire 伊予切, and Hōrinji-gire 法輪寺切 manuscripts belong to "completely the same line" of manuscripts, while Katagiri too wrote that "the texts of the Detchōbon manuscript and Konoe manuscript coincide even in minor points" and are "completely similar."<br> In this article, having been able to examine some materials not consulted by Horibe and Katagiri, I reexamine with respect to both format and text the position of the Konoe manuscript among manuscripts considered to have been copied during the Heian period, with a focus on its relationship with the Detchōbon, Iyo-gire, and Hōrinji-gire manuscripts. My findings can be summarized under the following three points.<br> (1) Regarding the presence or absence of particular lines of verse, if one excludes special cases, the Konoe manuscript coincides with the Detchōbon, Iyo-gire, and Hōrinji-gire manuscripts. However, some minor differences were found between the Konoe manuscript and the Detchōbon and Iyo-gire manuscripts.<br> (2) As for the arrangement of the poems, the Konoe manuscript coincides completely with the Detchōbon, Iyo-gire, and Hōrinji-gire manuscripts.<br> (3) As regards individual textual differences, the Konoe manuscript and the Det-chōbon, Iyo-gire, and Hōrinji-gire manuscripts share many identical passages, but some differences were also found, and in content too it would seem that the Konoe manuscript is different in character from the other manuscripts.<br> It has thus become clear that while the Konoe manuscript belongs to the same line of manuscripts as the Detchōbon, Iyo-gire, and Hōrinji-gire manuscripts, it differs somewhat in character from these three manuscripts.

2 0 0 0 銭痩鉄と谷崎潤一郎の周辺

- 著者

- 柿木原 くみ

- 出版者

- ASSOCIATION FOR CALLIGRAPHIC STUDIES

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2009, no.19, pp.9-22, 2009

The Chinese seal engraver Qian Shoutie 銭痩鉄 met in Shanghai the Japanese painter Hashimoto Kansetsu 橋本関雪, who invited him to his home in Kyoto, where Qian Shoutie resided for a time, carving seals for Kansetsu and his acquaintances and gaining a good reputation and trust among Japanese men of culture. Around the same time, the popular Japanese author Tanizaki Jun'ichiro 谷崎潤一郎 had asked a friend living in Shanghai to have an address seal and name seal made for him. The engraver commissioned by Tanizaki's friend was Qian Shoutie, and upon receiving the seals, Tanizaki extended his interests to the field of seal engraving. Tanizaki amused himself in the miniature world of seals and came into contact with a great many seal engravers.<br> Donald Keene has written of Tanizaki's works that they should be savoured in their individually published editions rather than in the form of his collected works. This is because Tanizaki's almost obsessive passion was poured into every aspect of the content and binding of his works. <br> In this article, basing myself on the association between the three artists Hashimoto, Qian Shoutie and Tanizaki and the inner depth of this association, I inquire into the engraver of the author's seals on the colophons of first editions of Tanizaki's works, and I also consider the seals used by Tanizaki for his personal use.

1 0 0 0 OA 明治初期の巌谷一六とその書法〈概要〉

- 著者

- 杉村 邦彦

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2017, no.27, pp.73-78, 2017-11-30 (Released:2018-03-23)

1 0 0 0 OA 天發神讖碑の筆法とその伝承について

- 著者

- 佐藤 法雄

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2005, no.15, pp.89-102, 2005-09-30 (Released:2010-02-22)

1 0 0 0 OA 龍眠会研究初探 ―彷徨する六朝書道をめぐって―

- 著者

- 中村 史朗

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2016, no.26, pp.31-44,117-116, 2016-10-30 (Released:2017-04-04)

As moves towards establishing institutional systems for art accelerated on the part of the administration during the Meiji 明治 era, calligraphy too underwent major changes. The realities of these changes were strikingly demonstrated by the emergence of the so-called Six Dynasties school of calligraphy. It is generally acknowledged that the Chinese scholar-collector Yang Shoujing 楊守敬 came to Japan with a large corpus of materials related to bronze and stone inscriptions, whereupon Kusakabe Meikaku 日下部鳴鶴 and other Japanese calligraphers who were stimulated by their contact with him established the new style of Six Dynasties calligraphy, sweeping away old calligraphic conventions. But this does not necessarily accord with actual developments thereafter. The new style of calligraphy proposed by Meikaku and others had a strong correlation with existing Tang-style calligraphy, and its character was such that it could be better referred to as “new Japanese-style calligraphy.” Subsequently the direction taken by Meikaku and others came to form the central axis of calligraphy during the Meiji era, but it was only natural that calligraphers and groups advocating a different orientation should have appeared, and the Six Dynasties school of calligraphy assumed a multilayered character. In this article, I first examine the actual substance of the Six Dynasties school of calligraphy as advocated by Meikaku and others, and then I undertake an examination of the activities of the Ryūminkai 龍眠会 (Society of the Slumbering Dragon) founded by Nakamura Fusetsu 中村不折 and others who lay at the opposite pole among the various parties espousing Six Dynasties calligraphy. Research into the history of Japanese calligraphy during the modern period has until now been primarily concerned with publicly recognizing outstanding calligraphers individually, and a stance that would clarify their relationships and trace historical developments has been wanting. In this article, I compare ideas of differing character that were put forward in relation to the Six Dynasties school of calligraphy while also ascertaining changes in calligraphy over time and the circumstances surrounding calligraphy with a view to making a start on forging links between past individual studies.

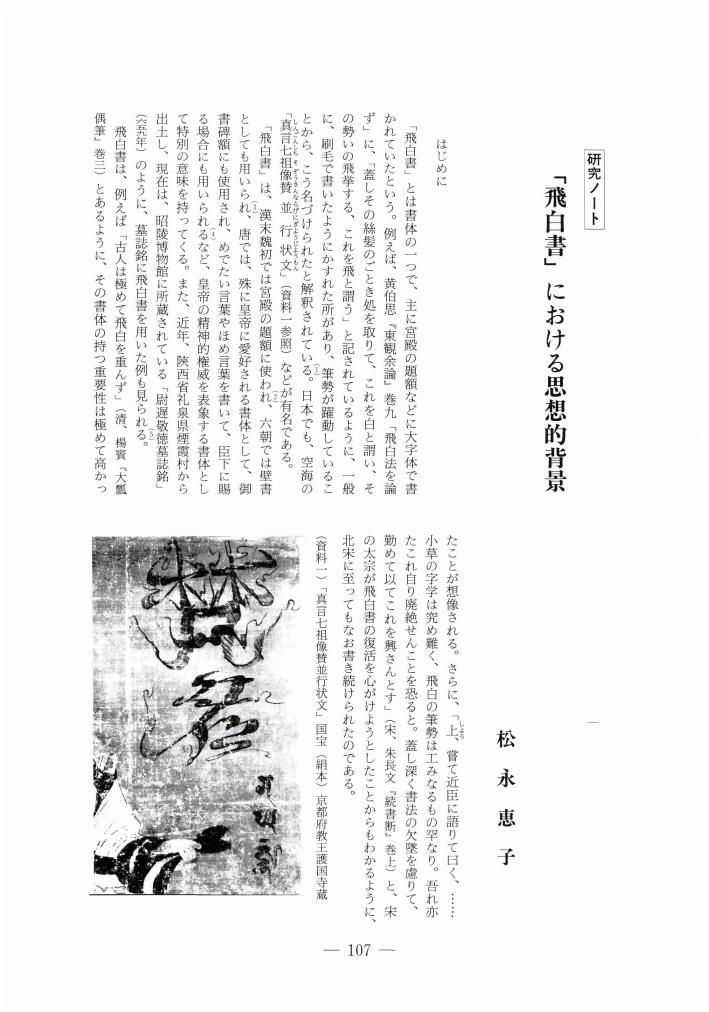

1 0 0 0 OA 「飛白書」における思想的背景

- 著者

- 松永 恵子

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.14, pp.107-121, 2004-09-30 (Released:2010-02-22)

1 0 0 0 OA 「扶桑再遊記」にみる羅振玉と日本人 ―社会的ネットワーク分析の視点から―

- 著者

- 菅野 智明 猿渡 康文

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2017, no.27, pp.1-16,83, 2017-11-30 (Released:2018-03-23)

The influx of vast quantities of Chinese painting and calligraphy following the 1911 Revolution has long attracted attention as an epoch-making event in terms of the history of artwork collections and the history of cultural intercourse. Luo Zhenyu 羅振玉 (1866-1940), who had moved to Kyoto to escape the upheavals of the Revolution, has been regarded as one of those who played a central role in this influx of Chinese painting and calligraphy into Japan, and he also deserves special mention in view of the fact that he took a lead in publishing photographic reproductions of these works. But prior to the Revolution Luo Zhenyu had made a tour of inspection of Japan in his capacity as an official of the Qing dynasty, and chiefly through his contacts with Japanese living in Tokyo who were well versed in Chinese culture he had managed to view various Chinese artefacts that had come to Japan, such as painting and calligraphy, stone and metal inscriptions, and books. Details of this are recorded in his diary, “Fusang zaiyouji” 扶桑再遊記 (1909). When analyzing the social network to be seen in this diary, the application of objective methods such as quantification becomes an issue. It would seem that it was the very structure of the network which was formed that had a greater influence on Luo Zhenyuʼs achievements during this visit to Japan than did the nature of his relations with individual Japanese with whom he came into contact. We consider the elucidation of this point to be also indispensable for gaining an understanding of his movements after he settled in Kyoto. In view of the above, in this article we apply the method of “social network analysis,” a quantitative method of analysis that has proven to be successful in the social sciences, with the aim of clarifying the structural characteristics of Luo Zhenyuʼs network of Japanese acquaintances to be seen in the “Fusang zaiyouji.” We also examine the possibility that the structure of this network may have had an influence on the achievements of his visit to Japan.

1 0 0 0 OA 初期羅振玉書画碑帖コレクションの日本への流入

- 著者

- 下田 章平

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2022, no.32, pp.57-70,128, 2022-10-31 (Released:2023-03-31)

In this paper, we mainly analyzed materials in the Naito Collection in Kansai University Library as part of Luo Zhenyu's research collection and examined the background of Luo Zhenyu's retreat to Kyoto to pursue his collection activities. We then further examined the Luo Zhenyu calligraphy, painting, and inscription rubbing collection (hereinafter the “Early Luo Zhenyu Collection”) and discussed the methods used to promote and sell them to Japanese collectors. As a result of the study, we found that Luo Zhenyu's decision to retreat to Kyoto was based on the arrangement by Fujita Kenpo, who determined that he would be able to raise the funds necessary to afford the expenses for the retreat and academic publishing. In fact, the initial cost of the Kyoto retreat was financed by the Uenobon Jushichijo. The sale of the Early Luo Zhenyu Collection also served to educate Japan about the reality of Ming and Qing calligraphy, paintings, and the good inscription rubbings and formed the core of the Ueno Yuchikusai and Onishi Kenzan collections. Yamamoto Jiho seemed to be inspired by such a movement and expanded the Ming and Qing calligraphy and paintings collection in a short period of time. Furthermore, the Luo Zhenyu collection was cataloged for sale in advance, and an exhibition of the collection was held. It should be noted that this later became a guideline for the collection group led by Inukai Bokudo in terms of methods of promotion and sale. In addition, we also found that Luo Zhenyu not only purchased the collection from Chinese collectors but also widely engaged in sales on their behalf and sales intermediation when the collection was transferred to the east. This suggests that a portion of the many calligraphy, paintings, and inscription rubbings released by the financially impoverished Qing imperial family and high-ranking officials flowed out through Luo Zhenyu to Japan, seeking a sales channel.

1 0 0 0 OA 何君閣道摩崖の書 ―四川省刻石に見る一形態―

- 著者

- 高澤 浩一

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2007, no.17, pp.13-28, 2007-09-30 (Released:2010-02-22)

1 0 0 0 OA 難波津の歌の享受史覚書 ―上代から『古今集』まで―

- 著者

- 安國 宏紀

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2009, no.19, pp.53-62, 2009 (Released:2012-02-29)

The Naniwazu 難波津 poem is known for the fact that it is associated with calligraphy practice in the kana 仮名 preface to the Kokinshu 古今集. But it is difficult to imagine that it was perceived as a poem for the practice of calligraphy from the time when it first began to be recited by people in ancient times. One needs to posit a process of reception, such that a poem which was originally unrelated to calligraphy practice was gradually associated with new functions as it gained acceptance, and then at a certain stage came to be understood in connection with the function of calligraphy practice. This article presents from such a viewpoint an overview of the reception and dissemination of the Naniwazu poem from ancient times to the Kokinshu. In Section 1, I first ascertain the fact that, judging from the repetition to be seen in its wording, the Naniwazu poem may be considered to have originally been a song from the district of Naniwa 難波. I also point out, again on the basis of its wording, that, by associating it with a ruler, it had the makings of a poem extolling his prosperity. Further, in view of the fact that "Naniwa" is used in connection with the emperor Kotoku 孝徳 and that importance was attached to Naniwa Palace and Naniwazu as centres of the reformist government centred on the emperor, I point out that the first ruler associated with the Naniwazu poem would have been Kotoku, and I suggest that the history of the reception of the Naniwazu poem began with its acceptance as a folk song, and during the reign of Kotoku it changed into a poem glorifying the emperor. In Section 2, I take up for consideration the attitude of obstructiveness towards Kotoku that is quite pronounced in the Man'yoshu 万葉集, and I argue that there is a strong possibility that from the late seventh century to the eighth century the Naniwazu poem was dissociated from Kotoku and came to be accepted by people in general. This dissociation of the Naniwazu poem from Kotoku may have added a degree of freedom to the poem's acceptance, resulting in the phenomenon of the multilinear coexistence of the Naniwazu poem with diverse functions, including calligraphy practice and wooden slips (mokkan 木簡) inscribed with poems, as can be seen in unearthed materials. I surmise that this multipurpose character of the Naniwazu poem is linked to the large quantity of unearthed materials from this period related to the Naniwazu poem. In Section 3, dealing with the references to the Naniwazu poem in the Kokinshu, its first recorded instantiation, I discuss as separate, independent materials relating to the reception of the Naniwazu poem the kana preface, which identifies it as a poem presented to the emperor Nintoku仁徳, the Chinese preface, which identifies it simply as a poem presented to an unnamed emperor, and an interpolated note, which views it as a poem that was composed by Wani 王仁 and presented to Nintoku. I conclude that the references to the Naniwazu poem in the Kokinshu have a multistratified structure in which there was superimposed on the Naniwazu poem's foundations of a poem extolling a ruler a connection with Nintoku by Ki no Tsurayuki 紀貫之, who was seeking to describe in the kana preface the ideals of waka 和歌 poetry, and a connection with Wani was further imposed by the interpolated note, which was based on the kana preface. In this article, I ascertain the character of the Naniwazu poem, which began as a song of the Naniwa district and, on the basis of its underlying potential to be associated with a ruler, developed in a multistratified manner as it formed connections with rulers such as the emperors Kotoku and Nintoku. At the same time, with regard to its functions, I show that the Naniwazu poem existed in a multilinear fashion, possessing a variety of functions that were not limited to the practice of calligraphy.

1 0 0 0 OA 〓石如の篆書に関する考察 ―李陽冰の影響を中心に―

- 著者

- 大迫 正一

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.14, pp.123-138, 2004-09-30 (Released:2010-02-22)

1 0 0 0 OA 庾肩吾『書品』攷 ―「天然」・「工夫」の淵源をめぐって―

- 著者

- 関 俊史

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2018, no.28, pp.1-14,104, 2018-10-31 (Released:2019-03-29)

Grading by “pin” was integrated in the form of “Xing san pin shuo” by the Dong Zhong shu school in the Han period, before being adopted by the government for employment and promotion under the name “Jiu pin zhong zheng System.” Since then, similar grading systems based on “pin” have been used in various fields, with the Shu pin by Yu Jian wu being one of the first among them. Several critical writings based on “pin” were subsequently published in rapid succession; extant studies have focused on the differences between Shu pin by Yu Jian wu and Shi pin by Zhong Rong. Shi pin by Zhong Rong explains that “qi” triggers the “xing qing” of a person into motion and encourages the person to sing and dance, evoking poetry. In other words, Shi pin argues that “qi” determines the grade of a text, a theory based on the chapter Yue ji of Li ji and Lun wen of Dian lun by Cao Pi. Shu pin introduces the grading ideas of “tian ran” and “gong fu” to determine “pin,” an approach that contrasts significantly with the Shi pin of Zhong Rong, who develops his theory around the idea of “qi.” Previous studies have indicated that the concepts of “tian ran” and “gong fu” were shaped by the influence of preceding theories of calligraphy. This article attempts to establish the origin of “tian ran” and “gong fu” in terms of character assessment. Furthermore, it redefines Shu pin as an activity of qing tan practiced throughout the six-dynasty period, and concludes that Yu Jian wu wrote Shu pin, influenced by qing tan.

1 0 0 0 OA 昭和初期における菊池惺堂の収蔵ネットワーク ―大橋廉堂先生入蜀画会を中心として―

- 著者

- 下田 章平

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2019, no.29, pp.73-87,103, 2019-10-31 (Released:2020-01-31)

This paper deals with Seido Kikuchi and Rendo Ohashi, who seem to have taken over the network of art collectors of Seido. I primarily examine Kikuchi Seido Nikki and some rare materials kept by the Ohashi family to reveal the network of Seido in the early Showa era. As a result of my examination, I conclude that Seido had a close relationship with the group of art collectors led by Bokudo Inukai in the early Showa era. In addition, I identify two important points that will help to reveal the bigger picture of the network of art collectors in the period from the Xinhai Revolution to the end of World War II, a transitional period in the history of art collection. First, the activities of collectors between Japan and China after Luo Zhenyu's return to China need to be researched. Second, the roles of the collectors in the network who were contemporaries of Seido Kikuchi (Senro Kawai, Rokkyo Sugitani, Sentaro Yamaoka, Kyozan Yamamoto, Hekido Tanabe, Ginjiro Fujiwara and Tatsujiro Hashimoto), as well as the roles of the collectors who led the next generation (Kikujiro Takashima, Yasunosuke Ogiwara and Tsuneichi Inoue) and of those in China (Choji Sasaki and Shunzaburo Kuroki), need to be considered. The network of Seido included many Japanese art collectors other than those mentioned above, but few points of contact between Chinese/Korean and Japanese art collectors, including their social relationships, have been confirmed; consequently, Chinese/Korean and Japanese art collectors are likely to have had separate networks. This fact will have to be taken into account when Chinese paintings, calligraphy and calligraphic rubbings are studied.

1 0 0 0 文字統一と秦漢の史書

- 著者

- 大西 克也

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2014, no.24, pp.93-103, 2014

1 0 0 0 OA 鋳物の技術と文字 —殷周金文の鋳造法をめぐって—

- 著者

- 山本 尭

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2020, no.30, pp.1-23,160, 2020-10-31 (Released:2021-03-16)

Despite a long history of research into the casting methods used for Jinwen in the Yin Zhou period—with a variety of hypotheses suggested to date—the actual methods used remained unclear. In light of this situation, the author has conducted multiple casting experiments with the cooperation of the Ashiyagamanosato Museum for the purpose of elucidating the casting methods used for Jinwen. This paper reports the results of the experiments and gives several preconsiderations against the background of changes in the lettering style used on Jinwen from the perspective of casting techniques. The results of our experiments conducted revealed that the so-called slip method, in which slip is applied repeatedly using a brush onto a plate buried in a core, most logically answers the questions about the casting methods used for Jinwen. Historically, this method was first suggested by RUAN Yuan of the Qing dynasty; in a sense, our experiments proved the validity of his suggestion after more than 200 years. Based on the success of our experiments in indicating the technical logicality of the burial method, the author also suggests that the casting method used for Jinwen introduced in this paper be named the “slip-plate method.” The experiment results do not rule out the possibility of other Jinwen casting methods. On the contrary, variations in technique are very likely depending on locations and time periods. During the Eastern Zhou period, some Jinwen letterings deviated from the typical Western Zhou style to show a significant proximity to the Zhuanshu style. These changes in lettering style suggest the historical background of changes in the casting method used from the slurry-plate to the model-carving method. Based on the above findings, further detailed examination of variations in Jinwen lettering styles is awaited in order to obtain detailed knowledge about the dissemination of the lettering culture during the Yin Zhou period along with the actual prevailing conditions. This will be an extremely important and significant research theme not only with respect to the history of the technique, but also for the histories of calligraphy and palaeography.

1 0 0 0 OA 中国古書論にみられる用筆理念の変遷 ―蔵鋒用筆を中心として―

- 著者

- 森 常雄

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1991, no.1, pp.103-124, 1991-06-30 (Released:2010-02-22)

1 0 0 0 OA 北大路魯山人と良寛書《縦読洹沙書》

- 著者

- 角田 勝久

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2018, no.28, pp.71-84,101, 2018-10-31 (Released:2019-03-29)

Ryokan (1758-1831), a Zen monk in the Edo period, is famous for his masterpieces such as “Hifumi, Iroha” and “Tenjotaifu.” However, his other large-scale work, “Judoku Goshasho” written on a large piece of paper (62.5 centimeters long and 329.4 centimeters wide) in large letters as high as 25 centimeters, remains relatively unknown. After its introduction in Ryokansama Meihinten published in 1963, “Judoku Goshasho” disappeared from all following collections of Ryokan works and exhibitions. However, once it was listed in Ryokan Ibokushu, published by Tankosha Publishing Co. Ltd. in 2015 and exhibited after an interval of half a century at the exhibition “Jiaino Hito Ryokan” held at Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art in September the same year, the work attracted wide attention. “Judoku Goshasho” is also noticeable as it was obtained by an artist Rosanjin Kitaokoji (1883-1959) in 1938, who, inspired by the work, completed “Ryokan Shibyobu” written in large kaisho letters in 1941. Against the traditional view that Rosanjin was deeply attached to Ryokan around 1938, reviews of Rosanjinʼs works listed in his collections of works revealed that he was already interested in Ryokan before 1927. After drawing a series of works which show his obsession to Ryokan, however, Rosanjin freed himself from the influence of calligraphies by Ryokan and completed “Iroha Byobu” with his original style in 1953 at the age of 70. This article concludes that Rosanjin’s “Iroha Byobu” is a result of close and detailed study of Ryokanʼs “Judoku Goshasho” by his side.

1 0 0 0 OA 偽刻家Xの形影 ―同手の偽刻北魏洛陽墓誌群―

- 著者

- 澤田 雅弘

- 出版者

- 書学書道史学会

- 雑誌

- 書学書道史研究 (ISSN:18832784)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2005, no.15, pp.3-21, 2005-09-30 (Released:2010-02-22)