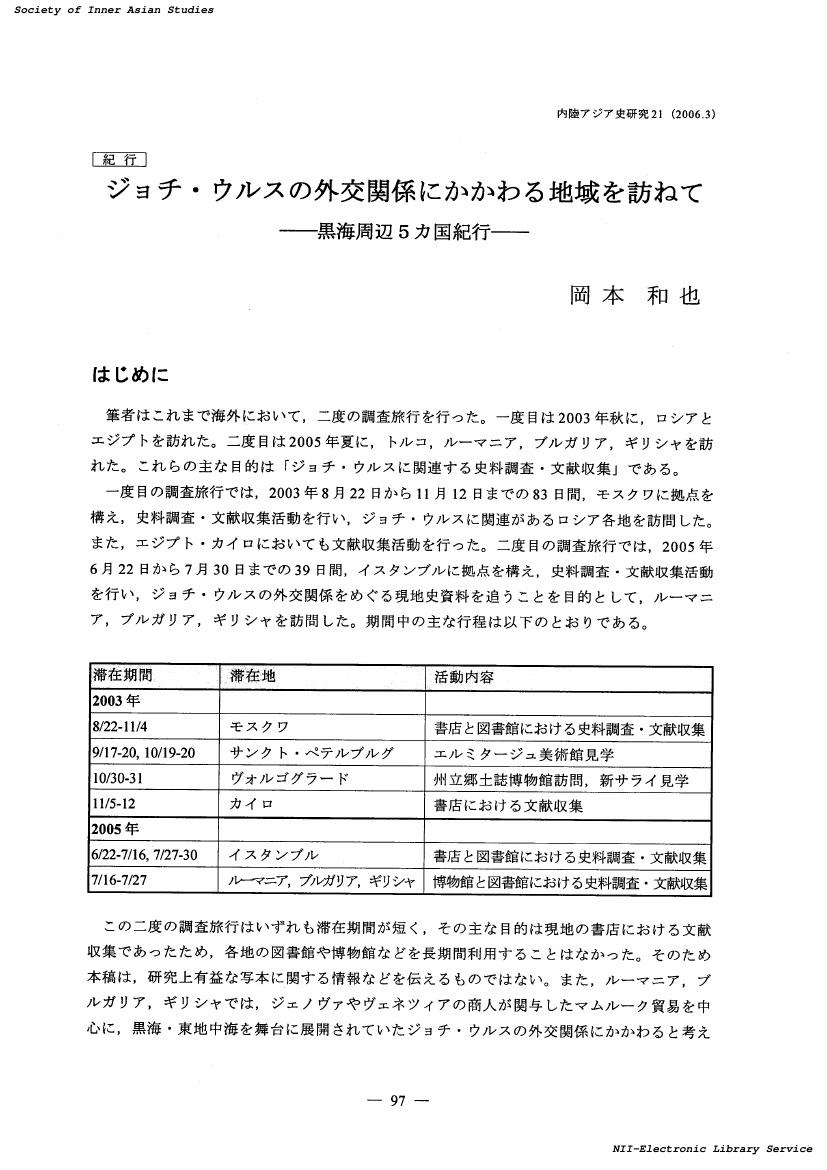

1 0 0 0 OA ジョチ・ウルスの外交関係にかかわる地域を訪ねて : 黒海周辺5カ国紀行(紀行)

- 著者

- 岡本 和也

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.21, pp.97-105, 2006-03-31 (Released:2017-10-10)

1 0 0 0 OA 最近,海外で開催された注目すべき中央ユーラシア史関係展覧会について(動向)

- 著者

- 中見 立夫

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.21, pp.107-113, 2006-03-31 (Released:2017-10-10)

1 0 0 0 OA 中国新疆維吾爾自治区档案館所蔵史料の閲覧について(動向)

- 著者

- 梅村 坦

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.21, pp.115-116, 2006-03-31 (Released:2017-10-10)

1 0 0 0 OA カシュガル・ホージャ家アーファーク統の活動に関する一考察 : 聖者伝に見るホージャ・ハサンの生涯と活動(公開講演・研究発表要旨,2005(平成17)年度内陸アジア史学会大会記事,彙報)

- 著者

- 河原 弥生

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.21, pp.135-136, 2006-03-31 (Released:2017-10-10)

- 著者

- 大出 尚子

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.25, pp.121-142, 2010

This paper examines the history of the National Museum of "Manchukuo" in terms of both political and scientific histories. The possession of the National Museum was initially comprised of three distinctive collections: property of the former Qing court, cultural artifacts of Chinese civilization, and excavated items. Over the years, however, the items in display changed. The scientific results of the Far Eastern Archaeological Society began to be reflected in the National Museum's exhibits, so the cultural artifacts of the Koguryo, Bohai, and Liao dynasties began to be featured prominently. The archaeological surveys conducted in the northeastern region of China at that time were intended to give substance to the history of "Manchukuo." In "Manchukuo," archaeological surveys of Bohai were given priority, because its exchanges with Japan could be historically confirmed this way. Furthermore, as the heartland of the Liao Dynasty situated in the region occupied by the Kwantung Army in the Battle of Rehe, archaeological results that would create the history of "Manchukuo" were expected from the survey. The exhibits of the National Museum reflecting the, excavation surveys conducted in line with the aforementioned political agendas were the exhibits that served to deliberately create the "Manchurian characteristics."

- 著者

- 三船 温尚

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.27, pp.123-124, 2012

1 0 0 0 突厥チョイル碑文再考

- 著者

- 鈴木 宏節

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.24, pp.1-24, 2009

1 0 0 0 「金帳汗国」史の解体--ジュチ裔諸政権史の再構成のために

- 著者

- 赤坂 恒明

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.19, pp.23-41, 2004-03

1 0 0 0 OA チンギス・ハーン祭祀の政治構造

- 著者

- 楊 海英

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.10, pp.27-54, 1995-03

- 著者

- 上村 明

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.31, pp.119-143, 2016

<p>In June 1930, over 430 Altai-Urianhai families moved across the Altai Mountains to Xinjiang, China. This "escape" triggered a chain of cross-border movements going out of Mongolia, initially in the region of western Mongolia and then spreading all along the border areas close to China. Altai-Urianhai's reports presented at the national congress meetings, as well as maps they produced and submitted to the governments, show that their territory had shrunk due to Kazakh domination of the region and unfavorable governmental policies. They stated that their motherland was the Chingel River to the west of the Altai Mountains, pleading for the government to return it to them. Furthermore, the government of the People's Republic of Mongolia, which was undertaking nation-state building, had started to introduce the school-education system and the conscription system. The Altai-Urianhai people considered not only those systems but also the government to be those of "Halha's", "red", and therefore "evil". In this context, they did not "escape" from their motherland, but rather returned to their homeland. Those suffering in other areas of Mongolia took the incident to be an "escape from the motherland" or a "form of resistance" rather than a "return home". In other words, they "de-contextualized" the incident from Altai-Urianhais' historical contexts, and "re-contextualized" it into their own positions in the situation of that time. Thus developed the mass refugee movements in the early 1930s in Mongolia.</p>

- 著者

- アローハン(阿如汗)

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.31, pp.93-117, 2016

<p>This paper discusses the case that a Japanese soldier, <i>Ryutaro Ito</i>, was invited as an instructor in the <i>Töb-i Sakikü Tangkim</i> school established by a noble of Kharchin Mongol's Right Banner, <i>Güngsangnorbu</i>. I then examined the circumstances and the historical background of this case, using materials of the National Institute for Defense Studies Library and the Japan Center for Asian Historical Records, Japanese newspaper articles and the Mongolian newspaper <i>Mongγol-un sonin bičig</i>, which had been published in Harbin. The schools founded by <i>Güngsangnorbu</i> had been discussed by many scholars from the viewpoints of Japanese intelligence activities and the domestic development of the Kharchin Mongol's Right Banner. Previous researchers evaluated founding schools in Kharchin Mongol as a modernization policy of <i>Güngsangnorbu</i>. However, in this paper I concluded that it had been carried out under a strategy of the Japanese Army. In addition, the Japanese Army was developing intelligence activities in Mongolia on the eve of Russo- Japanese War. This paper pointed out that <i>Ryutaro Ito</i> was dispatched for the military purposes of the Japanese Army against Russia.</p>

1 0 0 0 ロシア帝国の「イラン民族主義者」アーフンドザーデの帰属意識

- 著者

- 塩野﨑 信也

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.31, pp.49-72, 2016

<p>This article discusses the complex self-consciousness of Mirza Fatali Akhundzadeh (1812-1878). He is esteemed as one of founders of the Azerbaijani identity in the presentday Republic of Azerbaijan, but he is also regarded as one of the first 'Iran nationalists' in the context of the history of Iran. </p><p>It is true that he thought of Iran as his homeland and was proud to be an Iranian, but he also noticed non-Iranian elements in himself. For instance, he was not a native Persian speaker—he grew up speaking Turkic; he was an inhabitant of the Caucasus as well as a subject of the Russian Empire. Thus, he defined Iranians as descendants of the Ancient Persian Empires and insisted that his distant ancestors were connected to them.</p><p>He did not always recognize himself as Iranian. He used different group names depending on each situation. For example, when he spoke to Turkish people in the Ottoman Empire to enlighten them, he used 'Mellat-e Eslām (Muslims)' as a group name to communicate that he was one of them. He also called himself a 'Tatar' when he wrote letters to Russian officials. 'Tatar' was a Russian term applied to Turkic-speaking people in the Empire.</p>

- 著者

- 塩谷 哲史

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.31, pp.73-92, 2016

<p>This article analyses the factors behind the failure of the Amu River diversion project initiated by the Grand Duke Nikolai Konstantinovich in the territories of the Khanate of Khiva at the end of the 1870s. Shioya (2014) argued the details of the Grand Duke's project and the response of the government of Khiva to them, but the response of the general-governorship of Turkestan, the then supreme military-administrative organ of the Russian Empire in Central Asia, to the project still needs to be analysed. From the correspondence between the governor-general K. P. von Kaufman and a zoologist, D. Alenitsyn, it is evident that the former's response concerned the militarily strategic importance of the navigation of the Amu River, and the contemporary situation in Afghanistan, that is, the ongoing Second Anglo-Afghan war. Within the war ministry, the logistics connecting the navigation of the major river with the planned railroad between Central Asia and Russia were highly evaluated. In addition, the influence of the Duke's activities on the Turkmens in Khiva was also considered to bring instability to the khanate, regarding which Alenitsyn pictured the worst-case scenario, namely, the collapse of Russian rule in Central Asia with the spread of native disturbances initiated by the British-Indian army, if the army were to march through the Amu River basin. These factors, in line with the Grand Duke's misapprehension of the history and irrigation of the lower basin of the Amu, led to the failure of his diversion project.</p>

- 著者

- 石濱 裕美子

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.31, pp.145-163, 2016

<p>Carl Gustaf Mannerheim (1867-1951) travelled across Asia from Bukhara to Beijing from 1907 to 1908 to collect military intelligence for Russia. The diary he kept during this journey provides much information about Tibetan Buddhists under the influence of the Qing dynasty, namely Kalmuk, Torgut, Sirayogur, and Tangut, and contains a report of interviews with Torgut Khan's mother and with the exiled thirteenth Dalai Lama at Wu-taishan. Based on this information, this article clarifies that many Russian Tibetan Buddhists freely travelled to Tibet and Amdo and built relationships with Tibetan Buddhists in these regions. It also provides an outline of the photographs taken by Mannerheim during his journey and the antiquities of Tibetan Buddhism currently in the possession of the Finnish National Board of Antiquities.</p>

- 著者

- 小松 久男

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.27, pp.96-97, 2012-03-31

1 0 0 0 OA ティムール朝期の「一日行程」と駅伝制

- 著者

- 早川 尚志

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.30, pp.23-49, 2015-03-31

As is usually the case with Inner Asian dynasties that ruled vast territories, the TimuridDynasty operated a postal system, which encompassed an extensive web of postal stations.This system was instrumental in allowing the Timurids to acquire information rapidly,and it also facilitated the movement of both military personnel and civilians. The system was also used for time-tracking: For instance, citing how many postal stations there were between two cities proved to be a relatively reliable way of calculating distance. This truly demonstrates the importance of the postal system under the TimuridDynasty, especially as far as transport is concerned. In this paper, I examine the postal station as a criterion of time-tracking and relateit to a unit called farsaḫ or farsang. I also discuss the way in which the Timurid Dynastycould retain and manage the postal station as a constant criterion. Specifically, I examinethe system of postal stations, the permission needed in order to conduct a journey, howsuch permission was acquired, who could supply such permission, the benefits of suchpermission, and the support of the šiqāʾūls.The results of my investigation demonstrate how the Timurid rulers kept this web ofpostal stations in their lands and how they used them in order to obtain valuable informationas quickly as possible, especially during emergencies.

1 0 0 0 IR ティムール朝期の「一日行程」と駅伝制

- 著者

- 早川 尚志

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.30, pp.23-49, 2015

As is usually the case with Inner Asian dynasties that ruled vast territories, the Timurid Dynasty operated a postal system, which encompassed an extensive web of postal stations. This system was instrumental in allowing the Timurids to acquire information rapidly, and it also facilitated the movement of both military personnel and civilians. The system was also used for time-tracking: For instance, citing how many postal stations there were between two cities proved to be a relatively reliable way of calculating distance. This truly demonstrates the importance of the postal system under the Timurid Dynasty, especially as far as transport is concerned. In this paper, I examine the postal station as a criterion of time-tracking and relate it to a unit called farsaḫ or farsang. I also discuss the way in which the Timurid Dynasty could retain and manage the postal station as a constant criterion. Specifically, I examine the system of postal stations, the permission needed in order to conduct a journey, how such permission was acquired, who could supply such permission, the benefits of such permission, and the support of the šiqāʾūls. The results of my investigation demonstrate how the Timurid rulers kept this web of postal stations in their lands and how they used them in order to obtain valuable information as quickly as possible, especially during emergencies.

1 0 0 0 OA 中国社会科学院民族学人類学研究所所蔵のチャガタイ語・ペルシア語写本(史料紹介)

- 著者

- イスマーイール(白海提) バフティヤール

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.23, pp.139-151, 2008-03-31

- 著者

- イスマーイール(白海提) バフティヤール

- 出版者

- 内陸アジア史学会

- 雑誌

- 内陸アジア史研究 (ISSN:09118993)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.23, pp.139-151, 2008