14 0 0 0 OA 古い言語学と新しい言語学

- 著者

- 服部 四郎

- 出版者

- The Linguistic Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1975, no.68, pp.1-14, 1975-12-25 (Released:2010-11-26)

In the history of linguistics, several revolutionary developments in method have occurred, e. g. comparative grammar versus philology, synchronical linguistics versus historical linguistics, phonology versus phonetics, generative transformational grammar versus structural linguistics, etc. It is a peculiar feature of linguistics, however, that the new does not completely invalidate the old, and in the course of time the old and the new turn out to be comlementary.[The presidential inaugural lecture given at the 70 th general meeting of the Society held on 14 June 1975.]

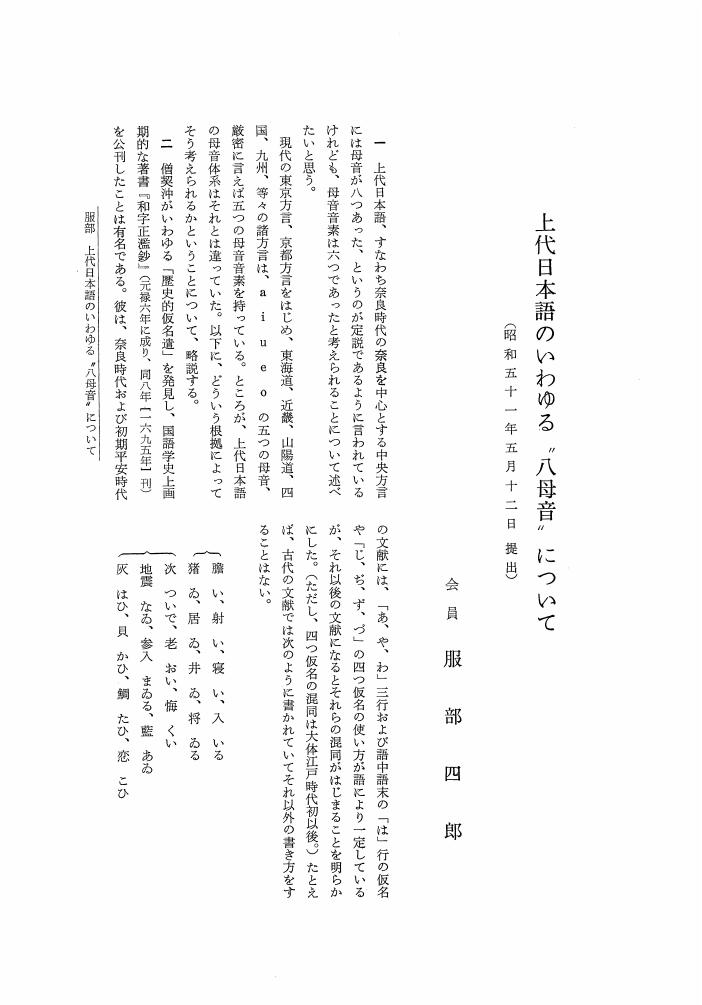

13 0 0 0 OA 上代日本語のいわゆる "八母音" について (昭和五十一年五月十二日 提出)

- 著者

- 服部 四郎

- 出版者

- 日本学士院

- 雑誌

- 日本學士院紀要 (ISSN:03880036)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.34, no.1, pp.1-16, 1976 (Released:2007-05-30)

- 被引用文献数

- 1

7 0 0 0 OA アイヌ語諸方言の基礎語彙統計学的研究

- 著者

- 服部 四郎 知里 真志保

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.24, no.4, pp.307-342, 1960-11-30 (Released:2018-03-27)

In 1955 and 1956, the authors and others were able to investigate the Ainu dialects, which were on the point of dying out. Some of the informants were the last surviving speaker or speakers of the dialects, and all of them were very old people. Some of them even have died since our investigation. In this article, we present the lexicostatistic data of 19 dialects, of which 13 are those of Hokkaido and 6 are those of Sakhalin. All the field work was done in Hokkaido. Some informants spoke Ainu fluently, but others spoke imperfectly and were unable to remember several words. In §4 (Table I on p.37∿p.59), the Ainu words are arranged according to Swadesh's 200 item list. In §5 (cf. Table II inserted), cognate residues are marked with +; non-cognates with -; cognates and non-cognates with±(when one or both of the dialects have two forms, and the inperfectness of the record does not allow us to decide which is more basic); questionable etymology or choice with ○; doubtful record with?; no answer given with・; lacuna of record with ( ). On Table II, all + have been omitted, except for ±. In §6, problematic points in the computation of residues are discussed. In §7 (Table III and Fig.2), the percentages of the residual cognates are shown in figures and graphs. In §8, the significance of the figures on Table III (Fig.2) is discussed. It is pointed out among other things that there is a remarkable gap between Hokkaido dialects and those of Sakhalin, Soya, the northernmost of Hokkaido, being the closest to the Sakhalin dialects. A significant gap is also seen between Samani on the one hand, and Niikappu, Hiratori, and Nukkibetsu on the other, which coincides with the discrepancies in other culture and customs, etc. In §9, the data on Table I are examined from the view-point of linguistic geography. In §10, questions concerning the computation of time-depth are referred to. In §11, the items, with regard to which the Hokkaido and Sakhalin dialects diverge from each other, are compared with those with regard to which the Ryukyuan and the Japanese dialects diverge from each other. It is found that the only common item in the two lists is 47. knee. Thus, it is possible to state that Ainu and Japanese have had the tendency to change in different directions, in so far as the 200 item list is concerned. In §12, it is pointed out that Japanese loanwords in Ainu and Chinese loan-words in Japanese are very few in so far as the list is concerned. Hattori does not think it impossible that the root √<kur> of Ainu and the forms of Japanese, Korean, Tunguse, and Turkic (on p.66) are cognates from the possible parent language of all these languages. It is hoped to promote comparative study of this kind.

6 0 0 0 OA 蒙古語文語の起源について

- 著者

- 服部 四郎

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1939, no.3, pp.1-27, 1939-09-25 (Released:2011-11-29)

- 参考文献数

- 17

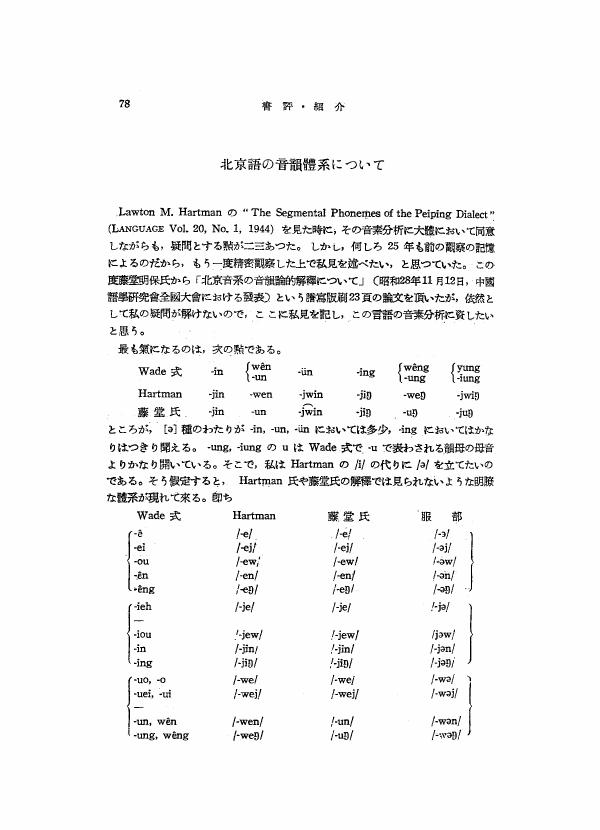

4 0 0 0 OA 北京語の昔韻膿系について

- 著者

- 服部 四郎

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1954, no.25, pp.78-79, 1954-03-31 (Released:2010-11-26)

3 0 0 0 OA ソスュールのlangueと言語過程説

- 著者

- 服部 四郎

- 出版者

- The Linguistic Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1957, no.32, pp.1-42, 1957-12-31 (Released:2013-05-23)

- 参考文献数

- 11

Analyzing and criticizing de Saussure's theory on langage, langue and parole', the author introduces his own distinction between the features of social habit and the individual features (which include the f. of individual habit, disposition and constitution and the casual f.), both of which, he maintains, are found in de Saussure's ‘parole’ and ‘la partie passive du circuit’, i. e. the psychological and physiological activity of the utterer, the sounds produced thereby and the physiological and psychological activity of the hearer (s).He criticizes Professor Tokieda's linguistic theory in terms of his own concepts ‘utterance’, ‘sentence’, ‘form’;‘utterer’, ‘expresser’, ‘first personer’ and ‘indefinite personer’.The ‘utterance’ is a unique speech-event, which includes the psychological and physiological activity of the utterer and the sounds produced thereby.The recurrent features of social habit in the utterances which are recognized as the repetions of ‘the same words’ by every speaker of a speechcommunity are defined as the ‘linguistic production’. A linguistic production consists of one or more ‘sentences’. A sentence is composed of an ‘intonation-pattern’ marking its end, one or more ‘taxemes’ and ‘forms’.(Cf. the, author's article ‘The analysis of meaning’ in For Roman Jakobson, 1956)The ‘expresser’ of a sentence is, according to the author, theoretically independent from the utterer of the utterance corresponding to the sentence.The ‘word’ is a minimal ‘free form’. The phonetic side of a word is called its ‘shape’, and its semantic side its ‘sememe’.In Japanese, nouns ‘indicate’, verbs and adjectives ‘indicate and express, ’ and enclitics and some suffixes ‘express.’ With relation to the expressing words and forms, it is necessary to discriminate between the ‘first personer’ and the ‘indefinite personer’. For instance, the form sizuka da «(it is) quiet» expresses the first personer's judgment, while the adjective atatakai «warm»expresses the indefinite personer's. The latter can take an interrogative intonation-pattern and make an interrogative sentence, while the former can not.

2 0 0 0 金と銀のさいころ : アルタイ系諸族の昔話

2 0 0 0 OA 言語の構造と体系

- 著者

- 服部 四郎

- 出版者

- The Linguistic Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1989, no.95, pp.1-31, 1989-03-25 (Released:2010-11-26)

- 参考文献数

- 21

Language, i. e. spoken language, is one aspect of human activity. A human being communicates with others in daily life, and language is one of the media of their communication. However, it is not a thing outside of him, but a phonomenon found in his activity itself.It is a social custom learned after his birth, but his mother influences him not only after the birth, but also possibly when he is still in her womb.A human being can easily become bilingual, trilingual, etc, if he learns the languages probably before his puberty. Adult people, however, find it difficult to learn a foreign language. It is necessary to scientifically confirm when and how his ability of learning his mother tongue solidifies.There are a few people who can exactly recite extremely long poems or historical legends, but everyone does not have such an ability. However, everyone can freely speak his native language.The languages in the world have various structures and systems, but certain circumstances necessitate them to have common features.Utterances can be short, long, or extremely long. One utterance includes one or more sentences, and one sentence includes one or more words. Why has an utterance such a structure?It is impossible to memorize whole sentences uttered by various people, to say nothing of whole utterances, because kinds of sentences are almost infinite and there is no limit of the length of sentences. However, one language has a finite set of words, and everyone can learn before his puberty the basic vocabulary at least with the grammatical rules which combine words into sentences.Words are combinations of a meaning (a concept) with a sound-shape. Children automatically acquire the concepts of the things and events in daily life, and they learn to combine a concept with a sound-shape which is approved by the linguistic community.In order to discriminate several thousand words of one language, the sound-shapes of words necessarily have some definite structure. Therefore, they are combinations of syllables, which consist of one or more consonants plus a vowel or a diphthong (plus one or more consonants).The set of consonants or vowels (and diphthongs) is not a random one, but a systematic one, so that it is easy to memorize them.The sets of consonants and vowels can be systematic on account of the distictive features, which are very easy for a human being to memorize, because they are due to the articulations which are innately possible for him.

2 0 0 0 OA 「言語年代學」即ち「語彙統計學」の方法について

- 著者

- 服部 四郎

- 出版者

- The Linguistic Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1954, no.26-27, pp.29-77, 1954-12-25 (Released:2010-11-26)

- 参考文献数

- 40

The author introduces Morris Swadesh's method of lexical statistics or glotnchronology to the linguistic circle of Japan, applying it to the comparative study of Old Japanese and modern dialects.He discusses its significance as a comparative method of related languages, and points out the following two major advancements. While the comparative method so far concerns the phonology and grammar rather than the vocabulary, Swadesh deals with the latter. Swadesh's method is statistical and accordingly more objective than the usual comparative method.Although it is possible to comment critically on the method at several points, its effectiveness in general should be acknowledged. For instance, there are no“concepts and experiences common to all human groups”(Salish Internal Relationships, 157), because the dispositions of the speakers of different languages are often different even to “the same things”, that is, the “sememes”(as the author calls them) of synonymous words of any two languages are often not identical. Thus, Japanese /me/«eye» denotes the eye which opens and closes rather than the eye-ball, while (Chakhar) Mongol/nüdä/ which is the only word for “eye” denotes the latter rather than the former. Nevertheless we can find words which refer to things and events common to all human groups, and thus we can generally fill Swadesh's questionnaire.

2 0 0 0 OA "言語年代学"即ち"語彙統計学"の方法について : 日本祖語の年代

- 著者

- 服部 四郎

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.19, no.1, pp.100-101, 1955-02-20 (Released:2018-03-27)

2 0 0 0 アイヌ語諸方言の基礎語彙統計学的研究

In 1955 and 1956, the authors and others were able to investigate the Ainu dialects, which were on the point of dying out. Some of the informants were the last surviving speaker or speakers of the dialects, and all of them were very old people. Some of them even have died since our investigation. In this article, we present the lexicostatistic data of 19 dialects, of which 13 are those of Hokkaido and 6 are those of Sakhalin. All the field work was done in Hokkaido. Some informants spoke Ainu fluently, but others spoke imperfectly and were unable to remember several words. In §4 (Table I on p.37∿p.59), the Ainu words are arranged according to Swadesh's 200 item list. In §5 (cf. Table II inserted), cognate residues are marked with +; non-cognates with -; cognates and non-cognates with±(when one or both of the dialects have two forms, and the inperfectness of the record does not allow us to decide which is more basic); questionable etymology or choice with ○; doubtful record with?; no answer given with・; lacuna of record with ( ). On Table II, all + have been omitted, except for ±. In §6, problematic points in the computation of residues are discussed. In §7 (Table III and Fig.2), the percentages of the residual cognates are shown in figures and graphs. In §8, the significance of the figures on Table III (Fig.2) is discussed. It is pointed out among other things that there is a remarkable gap between Hokkaido dialects and those of Sakhalin, Soya, the northernmost of Hokkaido, being the closest to the Sakhalin dialects. A significant gap is also seen between Samani on the one hand, and Niikappu, Hiratori, and Nukkibetsu on the other, which coincides with the discrepancies in other culture and customs, etc. In §9, the data on Table I are examined from the view-point of linguistic geography. In §10, questions concerning the computation of time-depth are referred to. In §11, the items, with regard to which the Hokkaido and Sakhalin dialects diverge from each other, are compared with those with regard to which the Ryukyuan and the Japanese dialects diverge from each other. It is found that the only common item in the two lists is 47. knee. Thus, it is possible to state that Ainu and Japanese have had the tendency to change in different directions, in so far as the 200 item list is concerned. In §12, it is pointed out that Japanese loanwords in Ainu and Chinese loan-words in Japanese are very few in so far as the list is concerned. Hattori does not think it impossible that the root √<kur> of Ainu and the forms of Japanese, Korean, Tunguse, and Turkic (on p.66) are cognates from the possible parent language of all these languages. It is hoped to promote comparative study of this kind.

2 0 0 0 附属語と附属形式

- 著者

- 服部 四郎

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1950, no.15, pp.1-26,103, 1950

The writer of this article classifies linguistic forms as follows _??_ is definition of various forms is as the following:<BR>A form which is never uttered separately (by means of pauses) from other. form (s) is a bound form; all others are free forms. A free form which cannot be uttered alone is a clitic; all others are independent forms.<BR>It is sometimes difficult, however, to distinguish clitics bound forms, because clitics are. generally, although not always, uttered jointly with other form (s)<BR>The author explains first how to identify various fractions of utterances as the same form. Then he proposes three points..s the criteria to determine whether a form-is a clitic or a bound form.<BR>I) If the form in question can be co: ined freely with various independent forms, which belong to different classes because their functions and inflections are different, it, is a free form, i. e. a clitic.<BR>2) If other word (s) or phrase (s) can be inserted freely. between two forms united semantically, both of them are free forms Accordingly the form in question is-a. clitic.<BR>3) If two forms combined can change their order of combination, the two forms are free forms. The phonological structure of a form cannot be utilised as a criterion, because many clitics have similar structtres to those of bound forms. Of course we cannot depend upon the_meaning, too.<BR>It must be noticed, however, that clitics have such phonological‘ structures as can be uttered separately from other forms, and they are very ‘regular’ in relation to the words, with which they enter into close combinations. Ehglish ’-s of the possessive case is a bound form, because it has not such a phonological structure as can be uttered alone. The-e of Latin puellae is a bound form, because i t is not regular. Compare puerT, hostis, cornas, diei.

2 0 0 0 OA アイヌ語における年長者層特殊語

- 著者

- 服部 四郎

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.21, no.3, pp.158-165, 1957-08-25 (Released:2018-03-27)

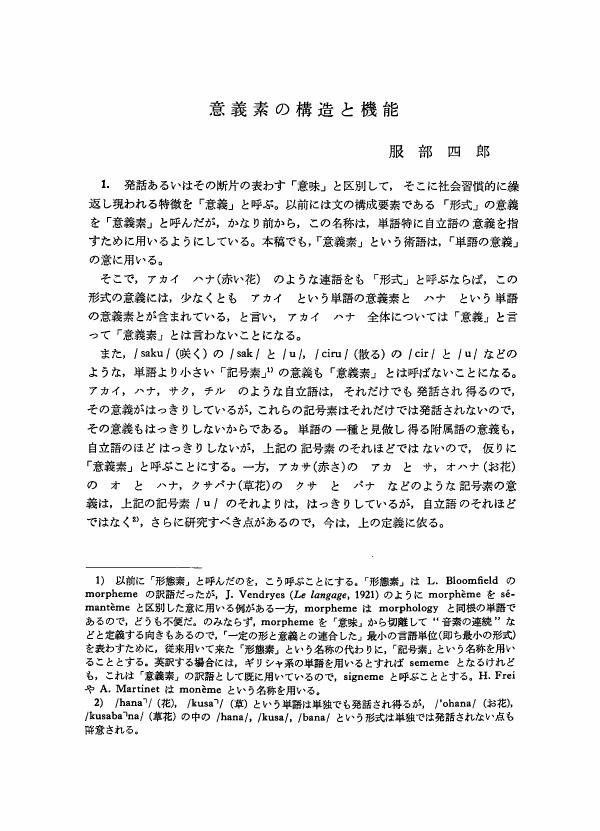

2 0 0 0 OA 意義素の構造と機能

- 著者

- 服部 四郎

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1964, no.45, pp.12-26, 1964-03-30 (Released:2010-11-26)

- 参考文献数

- 12

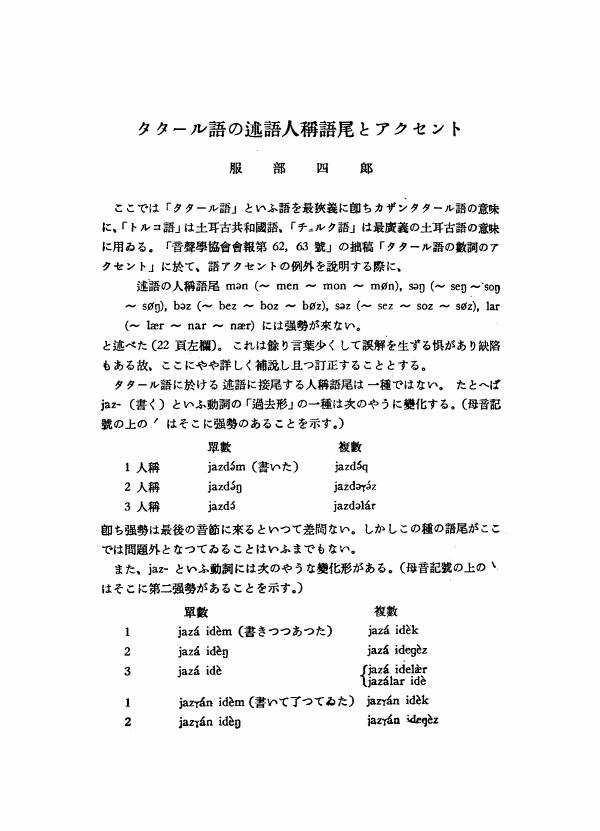

2 0 0 0 OA タタール語の述語人稱語尾とアクセント

- 著者

- 服部 四郎

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1941, no.7-8, pp.68-82, 1941-04-30 (Released:2010-11-26)

- 参考文献数

- 5

1 0 0 0 伊波普猷全集

- 著者

- 服部四郎 仲宗根政善 外間守善編

- 出版者

- 平凡社

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 1974

1 0 0 0 邪馬台国はどこか (昭和六十一年十一月十二日 提出)

- 著者

- 服部 四郎

- 出版者

- 日本学士院

- 雑誌

- 日本學士院紀要 (ISSN:03880036)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.42, no.2, pp.93-137, 1987

Firstly, the author agrees with Professor Taro Sakamoto's (M.J.A.) opinion to the effect that the ancestors of the Japanese nation came over to Japan from Siberia via the Mamiya Straits, Sakhalin, and Hokkaido in the early Stone Age. He also approves of Professor T. Sakamoto's theory that <i>Yamatai</i> Queendom was in Kyushu, not in Yamato (Nara Prefecture).<br>The author assumes that the distances described in the so-called <i>Gishi</i> <i>Wajinden</i> are those between the capitals of the kingdoms.<br>The author's hypothetic identification of the capitals of the kingdoms are as follows.<br><i>Matsura</i> Kingdom: Karatsu City including Sakura-no-baba.<br><i>Ito</i> Kingdom: Around the Mikumo-Iwara district in Maebaru Town.<br><i>Fumi</i> Kingdom: Umi City and the adjacent district.<br>As for the capital of <i>Na</i> Kingdom he advances a new theory that it must have been located in the area between Ko-no-su Hills and Mt. Higashi-Abura-yama in Fukuoka City.<br>In regard to <i>Toma</i> Kingdom, the author rejects all the theories advanced so far, and he proposes a new hypothesis that the capital was located around the consecrated spring of <i>Asaduma</i> in Kurume City.<br>The most problematic capital of <i>Yamatai</i> Queendom was located, according to the author, in Kumamoto City.<br>Probably around the end of the 3rd century A.D. it was destroyed to ashes by the Kumaso people (including that of <i>Kuna</i> Kingdom), a branch of the Japanese, who attacked <i>Yamatai</i> Queendom from the south, and the name <i>Yamatai</i> was abolished by them and passed into oblivion.

- 著者

- 服部 四郎

- 出版者

- 日本学士院

- 雑誌

- 日本學士院紀要 (ISSN:03880036)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.43, no.1, pp.21-27, 1988 (Released:2007-06-22)

- 被引用文献数

- 1