2 0 0 0 OA 三味線声曲における旋律型の研究

- 著者

- 町田 佳聲

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1983, no.47Appendix, pp.33-36, 1982-08-25 (Released:2010-02-25)

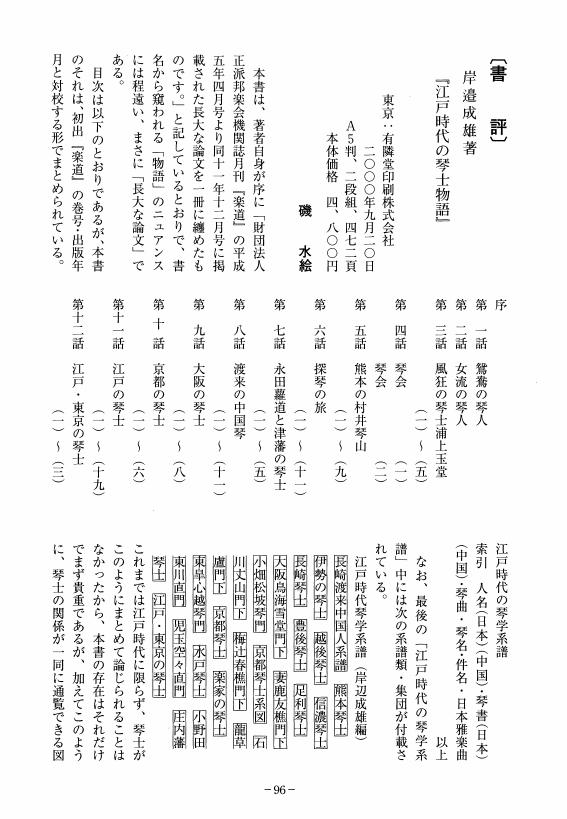

2 0 0 0 OA 岸邉成雄著『江戸時代の琴士物語』

- 著者

- 磯 水絵

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2001, no.66, pp.96-99, 2001-08-20 (Released:2010-02-25)

1 0 0 0 OA 台湾客家山歌の旋律の同一性

- 著者

- 東 暁子

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1988, no.52, pp.79-97,L8, 1987-11-30 (Released:2010-02-25)

- 参考文献数

- 17

The primary aim of this article is to clarify the ways in which the framework of melodic construction and the linguistic tones of a text interact in the process by which a melody maintains its melodic identity, and takes as its object a genre of folk-song of the Hakka _??__??_(Ch. Kèjia) of Taiwan, the mountain song (Ch. shange _??__??_). Secondly, an examination has been made of the present distribution of the mountain song, which originally spread from the regions inhabited by the Hakka in the northern part of the island, and treatment has also been made of the special characteristics of the musical activity of the Hakka of Taiwan, which centres on folk-song. This can be viewed as an attempt firstly to analyse the musical phenomena of a particular music-cultural sphere as a sound idiom that includes a model for the making of music, and further to grasp anew the meaning that these sound phenomena hold within the overall context that gives birth to the music.Within the mountain song, texts variable in nature are set according to fixed principles of melodic construction. Of three types into which the mountain songs of the Hakka are divided, the type called sankotsú _??__??__??_ (Ch. shangezi) has been dealt with here. After a brief examination of the elements that constitute the framework of melodic construction—the form that performance takes, musical form, verse structure of the texts, and the methods of text-setting, etc. —analysis has been made of the correspondence between melody and linguistic tone pattern, in the cases of two-word phrases and single-word phrases, and in terms of the treatment of the entering tone (_??__??_ Ch. rùsheng) that exists in Hakka languages as it does in many other southern variants of Chinese.As a result of this analysis, it has been shown that the melodies of sankotsú folk-songs basically correspond with the linguistic tones of their texts. This does not mean, however, that the movement of the melody agrees completely with the rising and falling intonation of the linguistic tones. At certain points where movement of the melody is limited by the maintenance of its identity as a single song, the influence of linguistic tone is hardly felt. In the case of two-word phrases, there are numerous examples when the second word does not retain the rising and falling movement of the appropriate linguistic tone. Speaking generally, it is rare for the melody to be able to represent all characteristics of any single linguistic tone; it is by expressing part of those characteristics, sometimes by means of rhythm and sometimes by means of pitch change, that contrast with other linguistic tones is effected.Consequent upon the results of this analysis is the supposition that the melodies of sankotsú folk-songs are sung according to the linguistic tones of the. Sìxiàn _??__??_ dialect of Hakka. Even those who speak in Hailù _??__??_ dialect appear to conform to the linguistic principles of Sìxiàn dialect as their “sung language”. Since folk-songs of the mountain song variety intrinsically possess many elements that are prescribed by the language of their particular region of origin, it is often said that it is difficult for them to overcome the barrier of language and spread further in geographical terms. If so, the mountain song of the Hakka of Taiwan, which is distributed among people who speak in different dialects of Hakka, would seem to have changed somewhat in character from the original mountain song.Next, consideration has been made of the historical process responsible for this distinctive geographical distribution, and of the central role that folk-song, mainly that of the mountain-song type, plays in the traditional musical activity of the people. The Hakka people of Taiwan are immigrants from a number of places on the continent. We may speculate that

- 著者

- 藤田 隆則

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2003, no.68, pp.85-90, 2003-08-20 (Released:2010-02-25)

1 0 0 0 OA 下北の村落共同体の音楽文化

- 著者

- 甲地 利恵

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1989, no.54, pp.1-45,L4, 1989-08-31 (Released:2010-02-25)

- 参考文献数

- 14

The purpose of this paper is to examine the social function of music transmitted in the village communities in the Shimokita region of Aomori Prefecture, in particular from the perspective of enculturation. The learning of a music within a community involves not only that music, but also the learning of various matters that are concomitant with it. This paper will therefore clarify the social structure of the communities in an attempt to understand the state of their music culture. It will then present an interpretation of how music has functioned within communal society, taking as an example the nomai of Ori in Higashidori-mura.A variety of types of folk music are transmitted in the Shimokita region. Almost all of them take the style of geino, that is performing arts, in which music, dance, and theatre come together. These include shishi-kagura (nomai and kagura), kabuki, matsuribayashi, nenbutsu (a type of wasan, colloquial Buddhist music), and several teodori. It is in the latter that the tendencies of the folk music of Shimokita are most clearly reflected. In the neighbouring regions of Tsugaru and Nanbu, folksongs developed as solo vocal pieces into what may be called a stage vocal art. In contrast, in Shimokita, folksongs are sung as an accompaniment to teodori, generally by a number of people together. Percussion instruments, taiko (drums) and kane (a type of small cymbal), are always used as well.The inclination of the music of Shimokita towards geino style is connected closely to the characteristic social structure of the communities of the region.Firstly, the primary industries of Shimokita were restricted by its cool climate and, up to the Second World War, did not produce adequately. For that reason, differences in economic well-being did not develop to the extent of dividing the society into classes. Within the community, the principle of not producing bunke (branch families) was observed, so that the division of property should not result in further poverty. Since the community is made up only of honke (head families), the status within the communities of each ie (family) is equal.One force that brings together these equal ie as a single community is that of the system of communal economy. (For instance, in a fishing community, the catch is sold through the community's fishing cooperative, and the profit is distributed equally between each ie, or used for communal purposes.)Another force is the existence of the ‘age group’. In Shimokita, a type of age grade system can be observed. The members of each ie participate in an appropriate group in accordance with their position in the ie. By doing this, they perform their roles as members of the community. Functions essential to communal life are traditionally distributed between the age groups. Those in festivals and ceremonies are especially well-defined.We may construe here that strong communal relationships of this type are reflected in the music culture of the communities, and further that the people living in them learn of ‘community’ (and, in turn, culture) by means of learning the music. Strong communal relationships between members of equal status were indispensable in the daily life of the Shimokita communities. The people play their part in this ‘community’ by participating in their appropriate age group, where they perform the music of festivals and ceremonies. This music, furthermore, takes the geino style. It is, in other words, music performed not alone but with others of the same age group. What is important in this case is not whether an individual is more skilled than his fellows, but rather whether he can participate in the realization of a geino by adjusting to them. The sense of collectivity or community that can be discerned in the style of the music

1 0 0 0 OA 長唄における「楽」の概念

- 著者

- 小塩 さとみ

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.64, pp.1-22,L1, 1999-08-25 (Released:2010-02-25)

- 参考文献数

- 21

The aim of this paper is to clarify the concept of “gaku” in nagauta. Some nagauta pieces include a section labeled as “gaku”. The “gaku” sections are usually interpreted as representing or musically describing gagaku, court music, though it has been pointed out that the “gaku” sections do not imitate the musical style of gagaku. This paper considers 1) the types of music represented in the gaku, and 2) musical characteristics which create the gaku-likeness.It is not only nagauta that uses the term “gaku”: other genres such as music in the no theater, offstage music (geza ongaku) in the kabuki theater, and Yamada school koto music also use this term. However, the meaning of the term “gaku” varies in each genre. In the case of music in the no theater, the gaku is a type of dance mostly performed by the main actor (shite) who plays the role of “China man”, and the accompanying hayashi ensemble plays a special rhythmic/melodic pattern which is also called gaku. The gaku section is recognizeable by this pattern and can be considered to be representing Chinese music. In the case of kabuki offstage music, a short shamisen piece named gaku is performed as a kind of background music during the opening scene of a palace or at the entrance of a nobleman on stage. Different from the case of no, the gaku in the kabuki theater has a strong connotation with the aristocracy and does not represent Chinese music. But, when the gaku pieces are played, the hayashi part accompanies the same gaku pattern as no music. Some Yamada school koto music also includes a gaku section, where the gagaku koto technique called shizugaki is often used. The gaku here represents or imitates Japanese court music gagaku.The types of music represented in the gaku sections of nagauta have a wider range since they adopt the concepts of gaku from other genres and add nagauta's original meaning to them. In addition to Chinese music, background music for the opening scene at the palace and Japanese court music, some gaku sections represent exquisite music heard in “Western Paradise”, and some are used as background music for a Buddhist saint's appearance.Then, what kind of musical characteristics make a section sound gaku-like? In order to extract the common musical features of the gaku sections of nagauta, twenty-four nagauta gaku sections and seven gaku pieces of kabuki offstage music, which have a close musical relationship with the gaku section of nagauta, have been analyzed. As a result of the musical analysis, the following eight features have been found: 1) slow tempo; 2) continuous pizzicatos (hajiki); 3) double stop technique; 4) special techniques such as kaeshi bachi, and urahajiki; 5) unnatural melodic movement; 6) coexistence of the plural melodies; 7) regular phrasing of four- or eight-bar; 8) the rhythmic/melodic pattern performed by the hayashi part named gaku. Of these eight points, 2), 3) and 4) create the “elegant” and “solemn” atmosphere by using special tone colors, while 5) and 6) produce the gaku-likeness by using melodic movements different from nagauta's usual melodic movements.Creating gaku-likeness can be related to two ways of giving certain meanings to a melody which are widely employed in nagauta pieces: one is to quote a phrase from or to imitate the style of other musical genres, and this is considered to bring the musical atmosphere of the original genre into a nagauta piece; the

1 0 0 0 OA 吉川英史、金田一春彦、小泉文夫、横道萬里雄監修『日本古典音楽大系』

- 著者

- 柘植 元一

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1984, no.49, pp.155-158,L26, 1984-09-30 (Released:2010-02-25)

1 0 0 0 OA 日本樂律論

- 著者

- 田邊 尚雄

- 出版者

- 社団法人 東洋音楽学会

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1936, no.1, pp.3-25, 1936 (Released:2010-11-30)

本稿は私が嘗て都山流尺八師匠の研究資科の爲めに、金澤市の大師範藤井隆山氏が編輯發行せる『都山流尺八教授資料』の第四號乃至第八號に流載したものを墓とし、之を補訂、抜萃して纒めたものである。

1 0 0 0 OA 藤内鶴了著『続・日本近代琵琶の研究-鳥口・調口を中心とした「さわり」の音響構造-』

- 著者

- 島津 正

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2000, no.65, pp.79-82, 2000-08-20 (Released:2010-02-25)

1 0 0 0 博覧会の舞踊にみる近代日本の植民地主義:琉球・台湾に焦点をあてて

- 著者

- 葛西 周

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2008, no.73, pp.21-40, 2008

本論文は、国家イベントとして近代盛んに行われた博覧会における音楽を、日本の植民地主義という視点から考察することを目的としたものである。西洋とは異なる状況下で進められた日本の植民地主義とその文化的影響について考察する上では、西洋/非西洋=支配/被支配という構図から離れ、個々の事例から植民地政策による波紋や同時代の社会的思潮を汲み取ることが特に必要である。そのような問題意識を踏まえ、本稿では明治三六年の内国勧業博覧会における琉球手踊および昭和一〇年の台湾博覧会における高砂族舞踊という二つの対象について考察した。<br>「見世物」として諸民族の生活が展示された内国勧業博覧会の学術人類館では、地域特有の風俗を、「普通」という基準を作る内地の人々の前で披露するのは「恥ずべきこと」という発想が、琉球に顕著に生まれていたことを確認した。主催側の内地から見れば「他者」の「展示」になるが、「展示」される側から見ると、同じ「自己」であると教育されてきた内地に「他者」としてラベリングされたことを意味する。これによって、内地から見た植民地像と植民地の側の自己イメージとの間にずれが生じ、植民地は「不当」なイメージに対峙すると同時に、自己の再認識を迫られたと指摘できる。他方で、台湾博覧会における高砂族舞踊のような伝統的な演目は、支配層によって娯楽として消費されていたが、その一方で高砂族舞踊の出演者が支配層の前での上演に対して拒絶反応をあらわにせず、少なくとも表向きは肯定的な反応を示していたことも確認できた。<br>日本の植民地主義という文脈から文化イデオロギーについてアプローチする際には、「同化」のみならず「異化」が持つ暴力性もまた軽視せざる問題であり、エキゾチシズムをもって植民地の舞踊を眼差すことへの内地人の欲求が「異化」を生み出したと言える。政策レベル/精神レベルで行われた「同化」と「異化」との間の歪みが、植民地時代に披露された芸能にも顕著に見られることを本論文では実証した。

1 0 0 0 OA 中国古代音楽思想研究 第一集

- 著者

- 水原 渭江

- 出版者

- 社団法人 東洋音楽学会

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1965, no.18, pp.207-231, 1965-08-20 (Released:2010-11-30)

殷〓の発堀とそのト辞の放釈が試みられて以来、殷人の物質文化、あるいは、精神文化の一端が窺知されるに至うたが、要するに、段の王朝とは、黒陶を作り、農耕を生業とした一民族であって、盤庚に引率されて、山東の基部の曲阜より河南の安陽に移住し、彩陶の夏民族を征服して建てた所の王朝であるといえる。その殷の王朝の頃に、どのような形式内容の音楽が存在していたかについて、卜辞とか金文資料並びに後時史料等によって、多少の考察を加えたのが、中国古代音楽思想研究の第一集である。

1 0 0 0 総論 (海外における日本音楽研究)

- 著者

- 柘植 元一

- 出版者

- 東洋音楽学会

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.59, pp.p102-107, 1994-08

1 0 0 0 日本歌謡研究資料集成

- 著者

- 竹内 道敬

- 出版者

- 社団法人 東洋音楽学会

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1984, no.49, pp.139-142,L7, 1984

Historical source material of good quality, valuable as it as an endless source of stimulation for researchers, is almost invariably high in price and difficult to obtain. For that reason, we must turn most often to the facilities offered by libraries, but in the case of important primary material, the rarer it is the more likely it is to be available for use only under strict regulations, and it is often impossible for younger researchers to actually touch and inspect at close range. In many cases, there is often no alternative to using typographical reprints of certain sources, an alternative that of course involves a number of other difficult problems. It is most important, however, that basic primary sources should be viewed in their original forms whenever possible.<br>Accordingly, the publication of this ten-volume series of basic source material in photographic reproduction, which makes possible an appreciation of the sources in the closest form to the actual object itself, should be highly welcomed. The contents of each volume in the series are as follows:<br>(Translator's note: It should be noted that there are certain problems associated with reading the names of these sources, some of which will be outlined below, and that not all possibilities have been included here; in most cases, the generally-accepted reading of the name in modern Japanese has been adopted.)<br>In all a total of 39 items are reproduced in full photographic facsimile, with commentary on the sources included at the end of each volume. The collection of such an amount of material was obviously quite a difficult task, and gratitude should be expressed towards those involved with publication, as well as the four supervisors of the series, Asano Kenji, Shida Nobuyoshi, Hirano Kenji and Yokoyama Shigeru.<br>A quick glance at the contents of the volumes reveals firstly that these source materials are all from the Edo period (<i>Kinsei</i>), and that the collection is therefore a collection of vocal sources of the Edo period. The first problem with the collection is, then, that its name is too wide, since there are of course a large number of source materials for vocal genres from earlier periods. A table of contents of the series given at the back of each volume (except for some reason Vols. 7, 9 and 10) includes the information that this is a collection of Edo-period sources, although this is not stated on the cover-box or spine of each volume.<br>There is a problem too with the range of material included in the publication. It would seem clear from earlier research in the field and from the title of the publication that more source material dealing with <i>shamisen</i> music should be included. It would be helpful if there was some sort of explanation for the reasons behind the choice of the 39 items, but unfortunately no such text can be found. Without such an explanation it is hard to evaluate the choice of materials and the editorial policy behind the publication. It would be helpful to have this included if there is any possibility for publication of a second edition.<br>Below is a short listing in no special order of a number of other problems associated with the publication, although it should be noted that these do not effect the value of the series as a whole; indeed they are likely to be problems that the supervisors and other contributors to the series have already noticed.

- 著者

- 塚原 康子

- 出版者

- 社団法人 東洋音楽学会

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1988, no.52, pp.43-77,L6, 1987

This article provides a detailed introduction to the musical materials of Udagawa Yoan (1798-1846) and undertakes an examination of them from the perspective of the introduction and reception of foreign culture. Although Yoan is well known as a scholar of European studies involved in the introduction of chemistry and botany from the West, little work has been done on his written works dealing with music. In this article, an examination of his draft translations that deal with European music, and their Dutch-language originals, has been undertaken, and comparison has also been made to his works that deal with the music of the Chinese Qing (Ch'ing) dynasty. Two of his draft translations of special importance, one entitled <i>Oranda hoyaku</i>: <i>Yogaku nyumon</i> (‘Translation into Japanese from the Dutch: Introduction to European music’) and one comprising sections dealing with music in <i>Oranda shiryaku</i> (‘Record of Dutch matters’), have been reprinted typographically and appended to the article as reference material (see pp 59-71 and 71-77 of the Japanese text).<br>The major results of this examination can be summarized as follows:<br>1. In addition to those of Yoan's autograph manuscripts dealing with music that have been mentioned in earlier research, namely <i>Shingaku-ko</i> (‘Examination of the music of the Qing [Ch'ing] dynasty’), <i>Oranda hoyaku</i>: <i>Yogaku nyumon</i> (see above), <i>Taisei gakuritsu-ko</i> (‘Examination of the musical pitches of the Great West’), <i>Gakuritsu kenkyu shiryo</i> (‘Materials for research on musical pitches’), and <i>Teito hiko tozai gakuritsu</i> (‘Secret manuscript on the musical pitches of East and West’), it was ascertained that major accounts dealing with European music can also be found in parts of <i>Oranda shiryaku</i> (see above). In addition, Yoan copied parts of the 16th-century <i>gagaku</i> compendium <i>Taigen-sho</i>, and possessed for reference purposes <i>Onritsu-ron</i> (‘Treatise on musical pitch’) of the Japanese Edo-period Confucian scholar Kondo Seigai. All of Yoan's manuscripts dealing with music are first drafts, and it is clear that he was not a specialist in musical matters. The materials are valuable, however, since there are no other materials from the late Edo period of this scope that are indicative in concrete terms of the various aspects of the contemporary reception of foreign music, especially that of Europe.<br>2. The musical materials of Yoan dealt with in this article can be broadly divided into three groups: manuscripts dealing with music of Qing (Ch'ing) dynasty China; draft translations dealing with European music; and Japanese materials on musical pitch either copied or used as reference sources.<br>3. Comparison of the two groups of materials dealing with non-Japanese music has shown that those dealing with the music of China are more practical, reflecting Yoan's contact with actual musical activity, since they include traced diagrams of instruments and a collection of texts with musical notation (a manuscript copy of <i>Seishin gakui</i> compiled by Egawa Ren). In contrast to this, his draft translations dealing with European music center on explanations of instruments and pitch theory, matters that can be argued without reference to actual musical practice.<br>4. In rendering technical terms used for European music, Yoan limited himself basically to transliteration of the sounds of the words in Japanese, although at the same time contrasting them with the notational signs of Qing (Ch'ing) music and the pitch-names used in <i>gagaku</i>, and making reference to the text <i>Onritsu-ron</i> mentioned above. Although isolated in nature because they deal with Western music, Yoan's draft translations can be viewed as a continuation of the tradition of research on musical pitch as undertaken by the Confucian scholars of Japan's Edo period.<br>5. The

1 0 0 0 OA 真言声明における反音曲の記譜法について -四智梵語讃を中心に-

- 著者

- 新井 弘順

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1983, no.48, pp.42-90,L2, 1983-09-30 (Released:2010-02-25)

The shomyo of the Shingon sect is divided into four classes according to modal usage:1. Rokyoku (pieces in the ryo mode)2. Rikkyoku (pieces in the ritsu mode)3. Hanryo-hanrikkyoku (pieces half ryo and half ritsu)4. HennonkyokuThe first three classes are distinctions based simply on modal usage, but pieces of the fourth class employ modulations of mode. Pieces of this class begin in one mode, be it ryo or ritsu, and change to the other mode, and finish after modulating back to the original mode. They are most common in the san (hymn) repertoire (comprising Sanscrit hymns [bongo no san] and Chinese hymns [kango no san], which have texts set in verses of four phrases) of which the Shichi bongo no san (“Sanscrit hymn of the Four Wisdoms”) is a representative example.The basic notation manual of Shingon shomyo (which includes the Nanzan shinryu, Shingi-ha chizan shomyo and Shingi-ha buzan shomyo styles) which has been transmitted until the present day, is based on the Gyosan taigai-shu (also called Gyosan shisho or more simply Gyosan-shu, compiled by Joe in 1496, revised in 1514 and printed in 1646) which is written in the goin-bakase (five-note notation) developed by Kakui in the 1270s (see photograph 1). In addition to this notation, referred to as hon-bakase or basic notation, each school uses its own supplementary system which transliterates and facilitates the reading of the original notation, and which is variously called kari-bakase or tsukuri-bakase (makeshift or fabricated notation). The tuning of each piece in the repertoire is based on the practice of the Shomyo ryakuju-mon of Ryuzen (1258-?). According to this source, the Shichi bongo no san is a hennonkyoku in ryo-ichikotsucho (ryo mode on D) or ryo-sojo (ryo mode on G). Beginning on sho or the second degree (i. e. E) of ryo-ichikotsucho, the piece modulates twice at intermediate points to ritsu-banshikicho (ritsu mode on B), and ends on the second degree (E) of ryo-ichikotsucho.The scale of Shingon shomyo is based fundamentally on the goin (five-note) scale structure (note names in ascending order kyu, sho, kaku, chi, u), and the special characteristics of each note in the scale depend on the mode of the piece (i. e. whether it is ritsu or ryo). A characteristic melodic ornamental figure called yu (or yuri), for instance, occurs on the kyu scale degree in ryo, and the chi scale degree in both ritsu and ryo. Pieces in the ryo mode characteristically begin and end on the kyu or chi degrees of the scale, while ritsu pieces begin and end on the sho or u degrees of the scale. However, the Shichi bongo no san appears to be an exception to this rule, since notwithstanding the fact that the piece begins and ends in a ryo mode (ryo-ichikotsucho), its initial and final notes are both the sho degree of the scale. In addition, the ornamental figure yu (yuri) is also found on the same degree of the scale, thus contradicting the usual practices of pieces in ryo modes. This contradiction is not only characteristic of this single piece, but can be seen in other pieces in the hennonkyoku group.Dr. Kindaichi Haruhiko has in his article “Shingon shomyo” (“Buddhist ritual chant of the Shingon sect”, Bukkyo Ongaku, Toyo Ongaku Sensho Vol. VI, 1972) attempted to explain the reason for the occurrence of these unusual features of the pieces in the hennonkyoku group. According to Kindaichi, the shomyo of the Nanzan shinryu school

1 0 0 0 琉球における中国戯曲の受容

- 著者

- 劉 富琳

- 出版者

- 社団法人 東洋音楽学会

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2007, no.72, pp.83-95, 2007

琉球は、一三七二年に中国と冊封朝貢関係を打ち立て、一六三四年に江戸上りが始まり、中国や日本からの文化を受けながら、さまざまな芸能を育んできた。<br>琉球組踊は、科白や音楽や舞踊などからなる琉球の伝統的歌舞劇である。組踊と日本芸能との比較についてはこれまで日本側の多くの研究者が言及し、組踊が能をはじめ日本芸能からの影響を受けたとみているが、これらの研究は中国戯曲との関連に触れていない。組踊と中国戯曲との繋がりは少数の研究者が言及しているが、琉球において中国戯曲はどのような状況にあったかについては、まだ研究が進んでいない。<br>本研究は、琉球に伝わった中国戯曲について記述した史料をめぐって、史料の面から琉球における中国戯曲の様相を明らかにしたいと思う。<br>本研究で使用する史料は主に使琉球録や江戸上り史料である。使琉球録は中国の冊封使が冊封活動の経過を書いた文書である。江戸上り史料は琉球江戸上りの経過を書いた記録である。<br>使琉球録については郭汝霖『使琉球録』(一五六一)、謝傑『琉球録撮要補遺』(一五七九)、夏子陽『使琉球録』(一六〇六)、胡靖『杜天策冊封琉球真記奇観』(一六三三) 及び袋中上人『琉球往来』(一六〇五) などの史料を調べ、一六世紀後半~一七世紀初頭、中国戯曲は琉球に伝わってきて上演されたことが分かった。<br>江戸上り史料について調べた結果、琉球の江戸上りの際に、琉球人が中国音楽 (戯曲) を演じたことが分かった。<br>以上の史料から見て、琉球における中国戯曲の受容は組踊に影響を与えただろうと考えている。

1 0 0 0 箏組歌本と砧物

- 著者

- 平野 健次 久保田 敏子

- 出版者

- 社団法人 東洋音楽学会

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1970, no.30, pp.41-83, 1970

1 0 0 0 OA 催馬楽の音階と旋法 和洋音楽の音階と旋法・各論のうち

- 著者

- 篠田 健三

- 出版者

- 社団法人 東洋音楽学会

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1965, no.18, pp.176-206, 1965-08-20 (Released:2010-11-30)

芝祐泰採譜「雅楽第二集催馬楽総譜」 (龍吟社、一九五六年) を用いて以下、催馬楽の旋法を考える。まず歌謡旋律の部分のみを対象として分析したい。

1 0 0 0 OA 筑紫舞の伝承について

- 著者

- 羽広 志信

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.64, pp.41-50,L5, 1999-08-25 (Released:2010-02-25)

This research is to state my hypothesis about Tsukushi-Mai. Presently living in Fukuoka city. NISHIYAMAMURA Koujusai who is the head of the Tsukushi-Mai school has orally transmitted the traditions. And I have written them down. There are six locations in which the traditions of Tsukushi-Mai is presently being taught. Around students are working the art of Tsukushi-Mai in the following areas, Fukuoka city Sawaraku, Fukuokaken Asakura-gun, Fukuoka-ken Dazaifu city, Kanagawa-ken Kawasaki city, Tochigi-ken Tochigi city and Hyogo-ken Himeji city.This research took place from November 1995 through February 1997. There were 13 orally transmitted sessions. What is now known as Tsukushi-Mai was handed down to Koujusai from KIKUMURA kengyou in the early years of the Shouwa era. Up until that time it was known as the art of Kugutsu. Currently there are close to three hundred recordings of this unique art form. It is of great interest that Koujusai's recollection of the time and her detailed memories.·Tsukusi-Mai has some important characteristics in its performance, for example, : Tsukushi-Mai is the Japanese traditional performing art to employ various pieces of music, which are rarely used for other Japanese dancing, such as Samisen-Kumiuta and Koto-Kumiuta.·The lyrics and composition of Tsukushi-Mai music is different to conventional music in parts.To write the whole text of the interviews with Koujusai on Tsukushi-Mai is not possible due to space constraints, so in this paper I would like to concentrate on three major characteristics: (1) the classification, (2) the unique composition and lyrics, (3) the principal performance type.Research of (2) and (3) provides the base for section (1). However, it is not possible to look into all facets, because the research was conducted by putting together the contents of talks given by Koujusai. In (2) examples given include “Tobi”, “Etton”, “Ruson-ashi” and “Hashiratsuki”. In (3) examples “Hayafune” and “Shikinokyoku”.There are 4 themes for the future.1. To find historical material that would prove the existence of KIKUMURA kengyou and Kugutsu who were involved with Tsukushi-Mai.2. To find historical material that describes the showings of Tsukushi-Mai from the present to the past.3. To analyze and characterize the relationships between the different types and forms of Tsukushi-Mai.4. To reintroduce Sasara, a musicial instrument which was said to have been used in the past.There are still many unknown and unclear points in the study of the art of Tsukushi-Mai, and in the future I wish to continue this research from many different angles. After this presentation I would greatly appreciate any information or thoughts you may have about my research.

1 0 0 0 民族楽器の大量生産

- 著者

- 柚木 かおり

- 出版者

- 社団法人 東洋音楽学会

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2006, no.71, pp.65-83, 2006

バラライカは三角形の胴に三本の弦をはった有棹撥弦楽器で、ロシアの民族楽器として広く知られている。この楽器には、音楽事典などに見られるような、板を張り合わせて作った粗末な自作楽器あるいは職人が製作した楽器であるというイメージが先行しがちだが、数量から言えば、工場で大量生産されたものが圧倒的に多い。本稿は、民族楽器の大量生産が文化政策の一環として行われた経緯と理念を一九二〇~三〇年代の五ヵ年計画との関連において分析し、楽器大量生産の後世への影響を考察するものである。<br>ソ連は、「資本主義諸国に追いつき、追い越せ」をスローガンに様々な政策を打ち出した。五ヵ年計画はもともと工業部門の発展を目的とした国家規模の計画であるが、そのうち第二次五ヵ年計画 (一九三三~三八) には特に芸術部門の組織化が含まれた。その計画書の冒頭には「安価で良質な楽器の普及が、社会の文化水準の高さを示す」と述べられており、実にその理念にしたがって民族楽器の国を挙げての大量生産が行われるようになった。<br>世界初の社会主義国ソ連では、文化は国によって計画、運営、管理されるものであり、その意味で「国営文化」だった。工場製の楽器の生産と流通によって、より多くの人々が楽器を手にすることができるようになり、その楽器とともに、政策施行者側が推奨した「文化的な」音楽文化も組織的に普及することになった。しかし楽器の普及は、他方で、「非文化的である」として当局が排除しようとした農民の伝統的な器楽曲や世俗的なレパートリーを根絶するばかりか、政策被施行者側の工夫により、逆に生き残らせるという結果をもたらした。それらは、政策施行者側の推進した工場製楽器によって現在も鳴り響いている。