11 0 0 0 OA 神津仙三郎『音楽利害』(明治二四年) と明治前期の音楽思想-一九世紀音楽思想史再考のために-

- 著者

- 吉田 寛

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2001, no.66, pp.17-36,L3, 2001-08-20 (Released:2010-02-25)

Kozu Senzaburo (1852-97) is known as one of the central figures of Ongaku-torishirabe-gakari (Institute of Music) in Tokyo, and also famous for his major writing, Ongaku-no-rigai (Interests of Music), which has been recognized as one of the earliest works of modern Japanese musicology. Quoting no less than four hundred and fifty documents, ranging from time-honored Japanese and Chinese books to the newest Western writings, this compilation shows us plenty of musical anecdotes and episodes taken from various places and periods in the world. Arguing fully the influences and effects of music on human nature, it established a solid basis in theory for the educational policies of the Institute. Although this writing has been examined within the cultural contexts in Japan and Asia, few scholars have argued it in relation to the Western musical thoughts. This article examines the following: (1) the sorts of Western documents Kozu quoted, (2) the reasons for his selection, and (3) the ways in which he appropriated them for his own purpose.Born in Shinano, young Kozu cultivated himself within the circumstances of the Confucian tradition. He went up to Tokyo in 1869 and then studied English at private schools. When the new government determined to send young talents abroad to survey the educational systems in the modern nations, he was selected as one of members sent to the United States. Kozu seems to have been a student of the New York State Normal School at Albany from 1875 to 1877. There he learned the modern methods of artistic education such as vocal music and drawing, and gained knowledge of contemporary Western literatures on music, especially by British and American writers, and therefore established his own view on music, chiefly based on theories of music education in America (L. Mason), anthropology (Ch. Darwin) and comparative musicology (C. Engel and A. J. Ellis) in England. He is distinguished from the twentieth-century Japanese musicologists, who were mostly attracted by the German aesthetics of music.Kozu's view on music fostered in his Albany years had a definitive effect on the policy of Torishirabe-gakari and subsequent music education in modern Japan. In 1881, he was appointed to one of the supervisors of Torishirabe-gakari, founded two years before. At the Institute, he taught English, translated foreign books on musical grammar and harmony and gave lectures on music theory and history. His first theoretical work appeared in Ongaku-torishirabe-seiseki-shinposho (Report on the Result of the Investigations Concerning Music), which is a collaborative work with Izawa Shuji, the head director of the Institute. It includes “Ongaku-enkaku-taiko (Outlines on the History of Music)” and “Meiji-sho-sentei-no-koto (On the Selection of National Anthem for the Meiji Era)”, both of which are brief but comprehensive. In the former the author argues, chiefly referring to C. Engel's An Introduction to the Study of National Music (1866), that the Western diatonic scale and the Eastern pentatonic scale both originate in the pentatonic scale of Ancient India, as the Indo-European languages do, and emphasizes that the effect and interests of music has universal values. Here, however, he altered Engel's original arguments to accommodate them into the so-called “eclectic” policy of the Institute. In the latter essay, while summarizing the history of national anthems in European countries, Kozu examines how we can make an effective song that attracts people's attention and make their temperament obedient to the government. This report can be regarded as an important step to his more elaborate plan of Rigai.Ongaku-no-rigai (1891) consists of three parts with twenty-four volumes and three hundred fifty chapters. Each part shows, from the beginning, “Music and People, ” “Music and National Government” and

9 0 0 0 口伝の行進曲:維新期における山国隊の西洋ドラム奏法受容とその継承

- 著者

- 奥中 康人

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.70, pp.1-17,L1, 2005

Western military music or the drum and fife corps was diffused in every corner of the earth with expansion of colonization in the late 19th century. It was not the art music but the new technology of maintaining the order in an army, especially in drill of an infantry. Since this technology was often mixed with different cultures of music, it assimilated into local community. In Japan, a number of Western-style drum corps with Japanese bamboo flute were founded in the end of Edo period.<br>In the first part of this paper, I made clear the social context and role of drum and drummer in a platoon <i>Yamaguni</i>-<i>tai</i> which was organized voluntarily to enter into the Boshin Civil War (1868). The leader Itsuki Fujino's daily war report serves to attain this purpose. Because the drum call and march were essential to the stable operation of modern tactics, they must be trained elaboratively during the War under the signal of drummer boy, who was employed from outside. Snare drum made them develop their physical ability as soldiers. Just before the end of the War members of <i>Yamaguni</i>-<i>tai</i> had learned how to play the snare drum or flute in order to participate in a triumphant return from Edo to Kyoto. They handed down two repertories for this parade on the next generation: "<i>Koshinkyoku</i> [March]" and "<i>Reishiki</i> [Ceremony], " which would have represented the legitimacy of the new Meiji Government backing up the Mikado.<br>In the second part, I focused on their drumming. Although at the present time <i>Yamaguni</i>-<i>tai</i> dresses in period military costume and blows pentatonic melodies on the bamboo flutes, we can point out some evidences enough to prove that their playing manner have its roots on Western music. In <i>Yamaguni</i>-<i>tai</i> the performance has been memorized by means of the onomatopoeic words and graphic notation for drum. Based on careful observation and analysis of their presentation, it is obvious that these two tools indicated exactly player's bodily movements of both arms rather than the sound itself. This onomatopoeia including "<i>Hororon</i>" (=once five stroke roll) and "<i>En Tei</i>" (=twice flam; "<i>En Tei</i>" is derive from Dutch "een twee") corresponds to well-known drum exercises for stick control: Drum Rudiments. For that reason we can conclude <i>Yamaguni</i>-<i>tai</i> to be a fine example of acculturation of Western Music in Japan. It should be stressed that they have been able to continue their oral tradition since the Meiji Restoration just because of unawareness of the origin of their own drum method. If we tried to translate their music into Western musical notation which was familiar to us, their physical movements could never survive no longer.

8 0 0 0 OA 二重イーミックス理論に向けて

- 著者

- 山口 修

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1983, no.48, pp.189-190,L16, 1983-09-30 (Released:2010-02-25)

During the last four years, two of which were spent in West Germany as a Humboldt scholar and two of which have been spent back here in Japan, my various experiences and research projects have given me a new insight into approaches to two problems, the further development of which seems to be my immediate task at the present moment. The first of all is the construction of a theory of “double emics”, which will become a central part of a topic with which I have been concerned for many years, namely, ethnomusicology as an ethnoscience. The second deals with the possibility of a new type of historical ethnomusicology, using diatronic indicators derived from ethnoscience, that will be inherently different from historical and musico-historical studies of the past.My time spent overseas was perhaps most valuable in that it forced me to reexamine my attitudes towards the so-called “etic” (scientific and objective) methods supposedly employed in studies of foreign music cultures. I have become rather suspicious of the supposed “objectiveness” that we are capable of employing in these situations. It seems unlikely to me that there is anyone who can thoroughly ignore the perspectives and methods of thinking that he has developed over the years and which have been shaped by his personal experience. If it is impossible to escape the binds of this acquired method of viewing things, then we cannot help being subjective in our perspectives. If it is true that only culture-carriers (i.e. members of a given culture) can have a truly “emic” perspective of that culture, students of the music of cultures other than their own face a difficult task in either trying to become temporary members of the society that they are studying, or in reverse, maintaining an independent perspective, although this often leads to the unfortunate phenomenon often seen in Western studies whereby a student of another culture uses the standards of his own culture to perform a so-called “etic” and “objective” evaluation of that culture. I think that it is necessary for us to strive towards the development of a double-layered “emic” approach, in which, while applying an emic approach to the music of a certain culture (or even sub-culture within a culture), we retain our own subjectivity as Japanese (or whatever), developing a Japanese method of thinking that will function as an emic approach on a second layer.The second problem, that of developing an historical ethnomusicology using diatronic indicators derived from ethnoscience, is one I have only begun formulating, the concrete realization of which is still incomplete. What can be said at the moment, however, is that aside from the written documents—historical records, musical manuscripts, etc.—that have been used in historical studies of music until now, there exists an enormous, perhaps even more important body of unwritten materials, such as oral tradition and transmission as reflected in the knowledge of the performers of the music and the actual performance itself, which can and must be used as historical source material. The historical perspectives sought for using this material do not necessarily denote those developed in the West, that is, the tracing of an absolute chronology of an aspect of culture, but may be more of the nature of a relative study of the large-scale cultural shifts to be seen within the culture. A planned study of the music of Oceania may prove to be an invaluable opportunity for developing an appropriate methodology for using non-written historical materials.

8 0 0 0 OA 博覧会の舞踊にみる近代日本の植民地主義

- 著者

- 葛西 周

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2008, no.73, pp.21-40, 2008-08-31 (Released:2012-09-05)

- 参考文献数

- 19

本論文は、国家イベントとして近代盛んに行われた博覧会における音楽を、日本の植民地主義という視点から考察することを目的としたものである。西洋とは異なる状況下で進められた日本の植民地主義とその文化的影響について考察する上では、西洋/非西洋=支配/被支配という構図から離れ、個々の事例から植民地政策による波紋や同時代の社会的思潮を汲み取ることが特に必要である。そのような問題意識を踏まえ、本稿では明治三六年の内国勧業博覧会における琉球手踊および昭和一〇年の台湾博覧会における高砂族舞踊という二つの対象について考察した。「見世物」として諸民族の生活が展示された内国勧業博覧会の学術人類館では、地域特有の風俗を、「普通」という基準を作る内地の人々の前で披露するのは「恥ずべきこと」という発想が、琉球に顕著に生まれていたことを確認した。主催側の内地から見れば「他者」の「展示」になるが、「展示」される側から見ると、同じ「自己」であると教育されてきた内地に「他者」としてラベリングされたことを意味する。これによって、内地から見た植民地像と植民地の側の自己イメージとの間にずれが生じ、植民地は「不当」なイメージに対峙すると同時に、自己の再認識を迫られたと指摘できる。他方で、台湾博覧会における高砂族舞踊のような伝統的な演目は、支配層によって娯楽として消費されていたが、その一方で高砂族舞踊の出演者が支配層の前での上演に対して拒絶反応をあらわにせず、少なくとも表向きは肯定的な反応を示していたことも確認できた。日本の植民地主義という文脈から文化イデオロギーについてアプローチする際には、「同化」のみならず「異化」が持つ暴力性もまた軽視せざる問題であり、エキゾチシズムをもって植民地の舞踊を眼差すことへの内地人の欲求が「異化」を生み出したと言える。政策レベル/精神レベルで行われた「同化」と「異化」との間の歪みが、植民地時代に披露された芸能にも顕著に見られることを本論文では実証した。

7 0 0 0 OA アル・キンデイーの音楽論

- 著者

- 新井 裕子

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1994, no.59, pp.1-22,L1, 1994-08-31 (Released:2010-02-25)

Al-Kindi (Alkindus in Latin, ca. 801-866), the first philosopher of the Islamic world, was a man of encyclopedic knowledge and wrote many treatises under the influence of ancient Greek philosophers. Thereby he built up a sound foundation of Islamic philosophy, which would be succeeded and developed by muslim philosopers such as al-Farabi (Alfarabius in Latin, ca. 870-950) and Ibn Sina (Avicennna in Latin, 980-1038), and by European scholars after the twelfth century. Music was regarded as a science adjacent to philosophy in ancient Greece and the Islamic world as well. Al-Kind's musical theory must hence not be neglected from such viewpoints.I have tried, in the course of the present paper, to give the full picture of al-Kindi's musical theory through analyzing all his extant treatises on music. These are the following four texts: 1) MS London: British Museum, Oriental Manuscript 2361, fols. 165r-168r; 2) MS Berlin: Staatsbibliothek, Wetzstein II, 1240, fols. 22r-35v; 3) MS Manisa: II Halk Kütüphanesi, Ms. 1705, fols. 107r-109v; 4) MS Oxford: Bodleian Library, Marsh 663, pp. 203-204, 226-238.The paper is divided into five parts dealing with lute ('ud in Arabic), various elements of music, compositional technique, the perfecting of musicianship, and theory of ethos. The first part describes al-Kindi's explanations on the strings, the method of tuning the strings, execution, the method of practice of 'ud as well as the size and the construction of this instrument. The second part deals with musical tone, interval, tune, transposition, and rhythm. The focus of the third part lies in types of composition; that of the fourth does in what is required to composers. The last part is divided into three sections: the strings of 'ud, colour, and smell.Throwing light upon the musical theory of al-Kindi, the paper have demonstrated that al-Kindi was not only an introducer of the Greek musical theory to the Islamic world but also an original theorist. He connected, for example, the four strings of 'ud with cosmology, and thought about the influence each string exerted upon the soul.Another grave issue have come up in the course of the paper: the importance of studying manuscripts and text critique. F. Rosenthal had already pointed out, in his article (1966), the possibility of the mixture of a work of al-Kindi and that of false-Euclid in some folios of MS Berlin. A newly discovered text, MS Manisa, was proved to be a different edition of some parts of MS Berlin. In addition, according to my opinion, MS London, the text being most popular among researchers, has some problems too.Certainly, MS London deals with various topics of music, but it is much different from the other texts in its contents. The number of strings of 'ud, for example, is five, like the later philosophers such as al-Farabi and Ibn Sina, according to MS London, whereas the number is four in the other texts; diagrams are included only in MS London; unlike the other texts, no idea of astrology is found in MS London.To settle this problem, the date of copying MS London may yield some clues. The manuscript was copied on November 29, 1662 from a manuscript written at Damascus in the middle of November 1224 based on “an imperfect and undependable” manuscript according to the copyist of MS London. It may therefore well be that there are some interpolations of copyists in MS London. One must hence be careful in citing this text for arguing al-Kind's theory; the full picture of his musical theory described in the present paper must also be renewed whenever the text critique is advanced and a new text is discovered.

6 0 0 0 OA 琉球音階再考

- 著者

- 金城 厚

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1990, no.55, pp.91-118,L8, 1990-08-31 (Released:2010-02-25)

- 参考文献数

- 17

It is the intention of this article to review the ryukyu scale, about which various theories have been proposed to date, and to make some propositions that may serve as the basis for future research on the subject.The first point at issue is the structure of the ryukyu scale. Koizumi Fumio has interpreted the ryukyu scale (do mi fa sol si do) as being formed from two disjunct tetrachords, each of which is, in his terminology, comprised of two nuclear tones at the interval of a fourth with one infixed tone. In this interpretation, the nuclear tones are do, fa, sol and do.On the other hand, Kakinoki Goro has proposed another interpretation, according to which the melodic movement of Okinawan folksong is ruled by a tertial nucleic structure. In his interpretation, the nuclear tones are do, mi, sol, and si.The second point at issue is the question of which of the ryukyu and ritsu scales is the older. Kojima Tomiko has concluded that the ritsu scale (including the ryo scale as a variant of the ritsu) is the older because it is seen in old-fashioned myth songs in certain remote villages in the Ryukyu region. On the other hand, Koizumi insisted that the ryukyu scale was far older than the ritsu.In the present author's view, there seem to be two different kinds of ryukyu scale in Okinawan music: one is a scale based on a tetrachordal nucleic structure (do mi fa sol si do), in which the nuclear notes locate at do, fa, sol and do; and the other is a scale based on a pentachordal nucleic structure (mi fa sol si do mi), in which the nuclear notes locate at mi, sol and si.The present author has undertaken an investigation of the finalis of all pieces in the repertoire of Okinawan classical songs accompanied by the sanshin (long-necked plucked lute), whose melodies are notated in kunkunshii notation in four volumes. Within the 195 pieces investigated, there are 83 pieces (43%) whose finalis is located at the fourth, while there are 42 pieces (22%) whose finalis is located at the third, fifth, or seventh. The former are based on the tetrachordal nucleic ryukyu scale. However, in the latter the fourth is not stable enough to be thought of as a nuclear note. The present author proposes a pentachordal nucleic ryukyu scale which has its tonic at the third, because through investigation it is possible to recognize that the third, fifth, and seventh function as nuclear notes, and among these the third is most frequently the finalis.It is possible to suppose that the ryo scale (do re mi sol la do) and the pentachordal nucleic ryukyu scale (mi fa sol si do mi) are parallel with each other. In both cases the scale consists of the following intervals: narrow, narrow, wide, narrow, wide, in ascending order. The pentachordal nucleic ryukyu scale, however, displays a little more contrast in terms of the width of its intervals.In the case of certain folksongs of Yaeyama, some of which are dealt with in this article, the pitch of notes in the melody as performed is subtly heightened or lowered, so that it is difficult to identify the scale as being ryo or pentachordal nucleic ryukyu. Therefore, the relationship between these two scales, which appear to be opposites, is, in fact, not dualistic but monistic in nature.Such a relationship is analogous to that of slendro and pelog in Javanese music. This is worthy of note for the purposes of future comparative research.The conclusions of the present author are as follows. In Okinawan music there are five scales: min' yo and ritsu, both based on a tetrachordal nucleic structure, are dominant in the Amami and Okinawa Islands; while ryo and pentachordal nucleic ryukyu, both based on a pentachordal nucleic structure, are dominant in the Yaeyama, Miyako and Okinawa Islands. A complex of these scales is

5 0 0 0 OA 地歌「黒髪」・長唄「黒髪」に関する一考察

- 著者

- 宮崎 まゆみ

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1984, no.49, pp.39-70,L2, 1984-09-30 (Released:2010-02-25)

This article deals with a musical study of the accompanied vocal piece “Kurokami” as it exists in the two different Edo-period vocal music genres, jiuta and nagauta, and reaches the conclusion that the jiuta piece is the older or original version of the two. The basic reason for this result lies in the fact that the jiuta shamisen and vocal parts as well as the nagauta shamisen part are basically identical in melodic movement, and this movement has been demonstrated to be based on the accent of Edo-period Japanese in the Kansai area. The setting of the text in this way indicates that the piece was most likely composed in the Kansai area. Jiuta was the music of the Kansai and nagauta that of the Kanto (Edo) areas, and it would appear unlikely that the nagauta version of the piece was the original since, if that was the case, it should be expected that the nagauta shamisen and vocal part should agree in melodic movement and present a version based on the accent of Japanese in the Edo region.

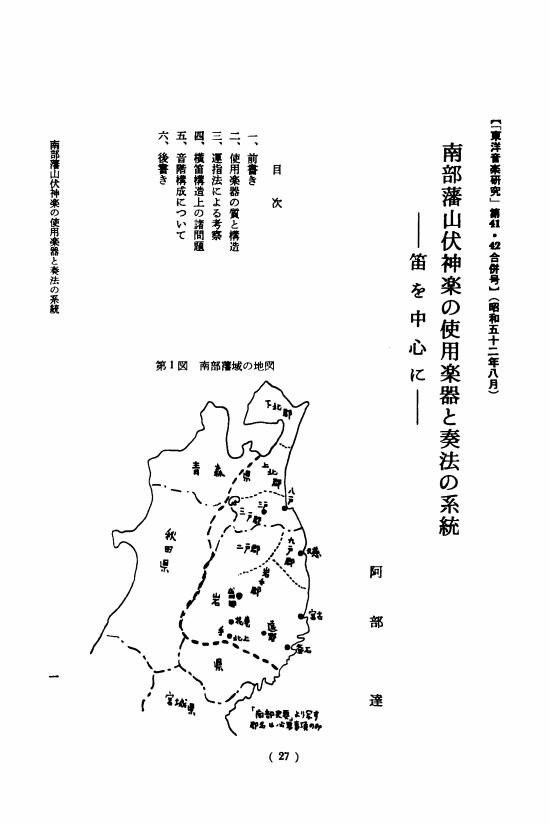

5 0 0 0 OA 南部藩山伏神楽の使用楽器と奏法の系統

- 著者

- 阿部 達

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1977, no.41-42, pp.27-56,en4, 1977-08-31 (Released:2010-11-30)

5 0 0 0 OA 口伝の行進曲

- 著者

- 奥中 康人

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2005, no.70, pp.1-17,L1, 2005-08-20 (Released:2010-02-25)

- 参考文献数

- 29

Western military music or the drum and fife corps was diffused in every corner of the earth with expansion of colonization in the late 19th century. It was not the art music but the new technology of maintaining the order in an army, especially in drill of an infantry. Since this technology was often mixed with different cultures of music, it assimilated into local community. In Japan, a number of Western-style drum corps with Japanese bamboo flute were founded in the end of Edo period.In the first part of this paper, I made clear the social context and role of drum and drummer in a platoon Yamaguni-tai which was organized voluntarily to enter into the Boshin Civil War (1868). The leader Itsuki Fujino's daily war report serves to attain this purpose. Because the drum call and march were essential to the stable operation of modern tactics, they must be trained elaboratively during the War under the signal of drummer boy, who was employed from outside. Snare drum made them develop their physical ability as soldiers. Just before the end of the War members of Yamaguni-tai had learned how to play the snare drum or flute in order to participate in a triumphant return from Edo to Kyoto. They handed down two repertories for this parade on the next generation: “Koshinkyoku [March]” and “Reishiki [Ceremony], ” which would have represented the legitimacy of the new Meiji Government backing up the Mikado.In the second part, I focused on their drumming. Although at the present time Yamaguni-tai dresses in period military costume and blows pentatonic melodies on the bamboo flutes, we can point out some evidences enough to prove that their playing manner have its roots on Western music. In Yamaguni-tai the performance has been memorized by means of the onomatopoeic words and graphic notation for drum. Based on careful observation and analysis of their presentation, it is obvious that these two tools indicated exactly player's bodily movements of both arms rather than the sound itself. This onomatopoeia including “Hororon” (=once five stroke roll) and “En Tei” (=twice flam; “En Tei” is derive from Dutch “een twee”) corresponds to well-known drum exercises for stick control: Drum Rudiments. For that reason we can conclude Yamaguni-tai to be a fine example of acculturation of Western Music in Japan. It should be stressed that they have been able to continue their oral tradition since the Meiji Restoration just because of unawareness of the origin of their own drum method. If we tried to translate their music into Western musical notation which was familiar to us, their physical movements could never survive no longer.

4 0 0 0 OA 一中節の旋律型分析-初世都太夫一中の作品を中心として-

- 著者

- 田中 悠美子

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2002, no.67, pp.1-22,L1, 2002-08-20 (Released:2010-02-25)

- 参考文献数

- 26

Itchu-bushi, a genre of joruri narrative, was originated by Miyako Itchu I in Kyoto in the Genroku era (1688-1703). There is debate as to whether pieces in the contemporary repertoire were composed by Itchu: some scholars feel that some of them may have been composed or revised by Miyako Kunitayu Hanchu (a student of Itchu I who later became independent and started bungo-bushi, another school of joruri narrative). Other pieces are thought to be compositions or revisions by Itchu V who revived itchu-bushi with the help of a kato-bushi shamisen player, Sugano Joyu I. Kato-bushi is also another school of joruri. Two factors make it difficult to identify the composers of joruri. Firstly, published texts are limited in number. Secondly, few records of performances exist due to the fact that compositions were not performed in the theater but in the salon.Nonetheless, there exist a core of pieces which are generally identified as Itchu's compositions. For this purpose of this paper, I selected twelve pieces, the names of melody types of which are identified in published texts. Ten pieces included in the staff notation form, compiled by the Hogaku Chosa-gakari (Department of Research in Japanese Traditional Music) which was attached to the Tokyo Ongaku Gakko (Tokyo Academy of Music) in the first half of 20th century; or in numeral notation form transcribed by Asada Shotetsu. I transcribed the remaining two pieces from sound recordings. Analysis of these twelve pieces in those contemporary notation has enabled me to classify melody types used by Itchu I in terms of their musical functions, identify the basic melodies (kihon-ji) which are used frequently in itchu-bushi narrative style, and observe the frequency of borrowings from other schools and arrangements of melody types used in each piece.The results of the analysis are as follows.(1) An itchu-bushi piece centers on the basic units (jishitsu tangen), is divided into sections by its connecting units (kessetsu tangen), and is varied musically by inserting figurative units (moyo tangen). Lots of melody types are related to other schools of joruri.(2) The basic units are classified into basic and borrowed motives. The former corresponds to the basic melodies (kihon-ji), and the latter comes from the other schools of joruri such as bungo-bushi, gidayu-bushi. Representative patterns of kihon-ji which listeners may perceive as typical itchu-bushi style are the patterns E, I and J of ‘futsu-ji’ in Score 2. The patterns named ‘haya-ji’ (hE, hI, hJ hK, hM, ) in Score 2 are also typical, and they are often quoted in the other shamisen music as typical itchu-bushi melody.(3) After studying the arrangements of melody types used in each piece, I can conclude that all twelve pieces analyzed contain melodies borrowed from other narrative genres. It is safe to say that the descendants of Itchu I (Hanchu, Itchu V and Joyu I) have added some revisions to the original pieces.

4 0 0 0 OA 琵琶秘曲伝授作法の成立と背景

- 著者

- 磯 水絵

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1983, no.48, pp.5-41,L1, 1983-09-30 (Released:2010-02-25)

This article has two aims: firstly, to investigate the procedures used in the transmission of secret pieces in the biwa (lute) tradition of the early medieval period, based on the examination of a number of written works describing the details of the ceremony performed for such transmission; and secondly, from the writer's standpoint as a researcher on Bunki-dan (a collection of tales concerning music history and focussing on the biwa, compiled around 1270 by Bunkibo Ryuen, a student of Fujiwara no Takamichi), to undertake a detailed description of the Nishi (lit, west) school of the biwa tradition which was founded by Fujiwara no Takamichi, student of the Myoon'in, Fujiwara no Moronaga (1138-1192), from its initial establishment until its eventual decay.The three manuscripts concerning the ceremony for transmission of secret pieces used as material in this study are as follows:1. Gakka dengyo shiki, myo (a manuscript in the Fushiminomiya collection of the Archives and Mausolea Department of the Imperial Household; also, included in Gunsho ruiju, 2)2. Biwa dengyo shidai (a manuscript in the Fushiminomiya collection of the Historiographical Institute of the University of Tokyo; also in Fushiminomiya gokiroku, 7)3. Biwa dengyo shidai (a manuscript in the collection of the Research Archives for Japanese Music, Ueno Gakuen College)The first manuscript is an Edo-period copy of a copy made by Saionji no Sanekane of the original proceedings of the ceremony written by the Myoon'in (Moronaga); the second is described in its colophon as the procedure handed down by Sanekane to his son Kanesue; and the third is described on its outside cover as being in the hand of Emperor Komyo (emperor of the Northern Dynasty, reigned 1336-1348, died 1380). Aside from the one important distinction concerning the site of the ceremony (i. e. whether it was held at the Myoondo, a temple dedicated to Myoonten [a variant name for Benzaiten, the goddess Sarasvati], or the house of the person receiving instruction into the secret tradition), there is no great difference between the proceedings written in each manuscript. It seems clear that the procedure defined by Moronaga continued to be employed in later centuries.The oldest record in extant historical sources concerning the proceedings of the ceremony is that of Shoji 2nd year (1200), 18th March, when Nijo no Sadasuke transmitted secret pieces to Morisada Shinno. Sadasuke himself was a student of Morinaga's, and it seems likely that the proceedings for the ceremony that he used were based on a precedent set by Moronaga, and that the ceremony itself was probably already an established practice at this time. Inferring from the evidence provided by the three manuscripts above, it is possible to say that the ceremonies practiced in the middle ages were all based on an original formula for the proceedings established at the end of the Heian period by Moronaga. Further inquiries into the later history of the secret piece tradition has shown that its central school was that of the Saionji family, and that two other schools, the Nijo school founded by Sadasuke and the Nishi school founded by Takamichi, existed as side branches.

4 0 0 0 OA 絵画資料に見る貞享以前の「三曲合奏」

- 著者

- 蒲生 郷昭

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2008, no.73, pp.43-61, 2008-08-31 (Released:2012-09-05)

本稿は、絵画資料にもとづきながら、「三曲合奏」はいつごろから行われていたのか、という問題を考察するものである。明暦元年 (一六五五) 刊の遊女評判記『難波物語』には、床に並べて置かれた三味線、箏、尺八を描いた挿絵がある。年代の明確な資料としては、箏の加わった三楽器の組み合わせの初見である。しかし、それより早い「元和~寛永年間初期」の作とされる相国寺蔵『花下遊楽図屏風』には、三味線と胡弓による合奏と、三味線と箏、胡弓による合奏とが、描かれている。さらに、ほぼおなじ時期の合奏を示すと考えられる、つぎの資料がある。すなわち、『声曲類纂』巻之一に「寛永正保の頃の古画六枚屏風の内縮図」として掲げられている二つの挿絵のうちの、遊里の遊興を描いているほうの挿絵である。これは模写であり、「古画六枚屏風」は現存しない。しかし、かつて吉川英史が『乙部屏風』として紹介した模本が別に存在する。二つの模写は構図と人物配置が違っていて、その点では『乙部屏風』のほうが、原本に忠実であると考えられる。『乙部屏風』でいえば、遊里場面の中ほどにいる十一人は、一つのグループを形成している。つまり、三味線、胡弓、尺八が伴奏する歌に合わせて踊られている踊りを見ながら、客が飲食している様子が描かれているのである。踊りを度外視すれば、そこで演奏されている音楽も、後の三曲の楽器による合奏にほかならない。すなわち、これらの楽器による合奏は、こんにちいうところの「三曲」が確立するよりかなり前の寛永ごろには、すでに行われていたことがわかる。これらの楽器をさまざまに組み合わせた絵はその後も描かれ、こういった合奏が早い時期から盛んに行われていたことをよく示している。その流れをうけて、こんにちの三曲合奏につながる合奏が行われるようになるのである。

3 0 0 0 OA 東亜の音楽

- 著者

- 梅田 英春

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1998, no.63, pp.170-173, 1998-08-20 (Released:2010-02-25)

3 0 0 0 OA 仏教打楽器の音響学的研究 (その一) 木魚・魚板・拍子木・板木・雲板・馨・鐃〓について

- 著者

- 栗原 正次

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1974, no.34-37, pp.19-51, 1974 (Released:2010-11-30)

3 0 0 0 OA 加賀藩の瞽女と瞽女唄

- 著者

- ジェラルド グローマー

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1994, no.59, pp.23-42,L2, 1994-08-31 (Released:2010-02-25)

The Kaga domain of the Tokugawa period (1603-1868) comprises what are today Toyama and Ishikawa Prefectures. In the past, many blind female performers known as goze wandered throughout this area, singing songs and playing the shamisen. Although the goze of neighboring Niigata Prefecture have been the subject of much research and documentation, the goze of the Kaga domain have as yet received almost no scholarly attention. This study seeks to fill this gap.Records of goze in the Kaga domain go back to 1619, when blind entertainers were sent to entertain the widow of the first head of the domain. Records of goze living in rural villages around Kanazawa also exist from the early seventeenth century.In the Toyama area, goze are recorded as being affiliated with a temple in the city of Takaoka. Later, these goze appear to have entertained visitors to the city's pleasure quarters. Both in Toyama and Ishikawa Prefectures, goze seem not to have formed the types of guilds that one finds in Niigata Prefecture.The last renowned goze of the Toyama area was Matsukura Chiyo (1884-1946, also known as “Chiima”). Recordings of her performances are almost entirely lacking, but people of the area still remember her songs and her activities. The latter half of this study attempts to reconstruct Matsukura's life, tours, and repertory. Several musical examples of performances as remembered by natives of Toyama Prefecture are presented, as is a photograph of Matsukura and her daughter Hana.

3 0 0 0 OA 馬淵卯三郎著『糸竹初心集の研究-近世邦楽史研究序説-』

- 著者

- 野川 美穂子

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1994, no.59, pp.125-127, 1994-08-31 (Released:2010-02-25)

3 0 0 0 井野辺潔・網干毅編著 『天神祭-なにわの響き』

- 著者

- 小西 潤子

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.60, pp.111-114, 1995

3 0 0 0 OA 貴人と楽人

- 著者

- 石田 百合子

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1989, no.53, pp.43-71,L8, 1988-12-31 (Released:2010-02-25)

This article is a chronological record of the life of Nakahara Ariyasu, written in the form of Ariyasu's diary. This diary itself does not actually exist, and in this sense the account is fictional.Nakahara Ariyasu was a musician who served under Kujo Kanezane (1149-1207) from the end of the Heian period to the beginning of the Kamakura period. He taught the biwa to Kanezane, as well as to Kamo no Chomei. A record of his statements and teaching about the biwa, organized and classified by one of his students, exists in the form of Kokin kyoroku. The present author has described its contents and expression in Vols. 1 and 3 of Jochi daigaku kokubunka kiyo (“Bulletin of the Japanese Literature Department of Sophia University”). This article follows on these previous articles as a chronological record of Ariyasu's life. The reasons why it has been written in the form of a diary are, firstly, to demonstrate the close connection between the range of Ariyasu's life and art, and the political stance as well as religious and cultural activities of the Kujo clan, and secondly, by superimposing the daily activities of Ariyasu and Kanezane, to contrast in concrete terms the difference in meaning that music and dance had to the two men, a musician and a noble respectively.Kujo Kanezane was the son of the Kanpaku (Regent) Fujiwara no Tadamichi, and became Utaisho (Major Captain of the Right) in Oho 1st year (1161) at the age of thirteen, later ascending to Naidaijin (Great Minister of the Centre), Udaijin (Great Minister of the Right), Sessho (Regent for an Emperor who is still a minor) in Bunji 2nd year (1186) and finally Kanpaku (Regent) in Kenkyu 2nd year (1191). He fell from power in Kenkyu 7th year (1196), and died in Jogen 1st year (1207) at the age of 59.Ariyasu served in the Kujo clan from the time when Kanezane was Utaisho, but at the same time held a number of official posts. According to surviving records, he held at various times the following posts: Minbu-no-jo, Minbu-no-daifu Hida-no-kami, Chikuzenno-kami, and Gakusho-no-azukari.The time during which this master and servant lived was one of great disturbances. The Hogen and Heiji Insurrections (1156 and 1160 respectively) were followed by the Genpei War, the great war between the Minamoto and Taira clans of 1180-85 that resulted in the victory of the Minamoto. The capital Kyoto was ravaged by great fires, earthquakes, and famines, and political power was steadily passing from the hands of the nobles to those of the warrior class. Kanezane's diary, Gyokuyo, gives a detailed description of movements in the contemporary political scene, and is of immeasurable value as historical source material. There is no source more valuable than this, too, for investigating the state of cultural aspects of the time, such as ceremony, religion, waka poetry, and music.Kanezane's concept of the ideal member of the noble class envisaged a person with grace who balanced equal ability in the fields of politics, ceremony, literature and the performing arts. Looking at examples from the latter field at the end of the Heian period, we can note the Cloistered Emperor Goshirakawa, who showed an almost deranged fascination for the popular vocal form imayo, while the famous musician Myonon-in Fujiwara no Moronaga devoted all of his energies to completing a comprehensive study and documentation of the gagaku, especially kangen, tradition. This attitude of becoming overly preoccupied with a single thing differed from Kanezane's ideal. This was rather a person who possessed the finest knowledge, understanding and discernment in a wide range of fields, from politics to literature and music, and who showed no special partiality towards any of them. He tried to educate his sons in this way. Kanazane himself pursued this image of the ideal Heian-period noble, and almost realized it; the one great difference between his

2 0 0 0 OA 明治・大正期の演歌における洋楽受容

- 著者

- 権藤 敦子

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1989, no.53, pp.1-27,L4, 1988-12-31 (Released:2010-02-25)

This article examines the way in which the music imported from the West during the Meiji (1868-1912) and Taisho (1912-1926) periods, as well as music that was formed in Japan under its influence, was incorporated into the enka of those periods. By viewing the change in this music during this long period of almost fifty years, it also seeks to clarify one aspect of the reception of Western music by the general populace of Japan.The introduction of Western music, which began around the end of the Tokugawa and beginning of the Meiji periods, has since exerted a substantial influence on the musical culture of Japan. However, although considerable research has been undertaken with regard to the reception of Western music by official bodies such as the Ongaku Torishirabegakari (‘Institute for musical investigation’, affiliated to the Ministry of Education), the question of how the general public received this music is one that has gained little attention. Among reasons for this are, firstly, that there are limits in terms of research material since data of relevance are unlikely to be found in official records, and secondly, that the term “general populace” includes a variety of peoples of differing cultural and social backgrounds, thus making it difficult to deal with the reception of music by the general populace as a single category.Accordingly, to bring about a detailed understanding of the various modes of reception of Western music, it is necessary to clarify each of them in turn by approaching it from a variety of angles. An attempt has been made in this article to survey one aspect of the reception of Western music by the general populace by means of examining changes in the music of the enka sung by enkashi (enka performers) during the Meiji and Taisho periods, which met with wide popularity at the time.In its present usage, the word “enka” refers in general terms to popular songs of the kayokyoku genre that are said to have “Japanese” musical and spiritual characteristics. Originally, however, enka were used along with kodan (narrative) and shibai (theatre) as a means of transmitting the message of the Meiji-period democratic movement to the general populace in a readily understandable form. Songs sung by the proponents of this movement were known as “soshi-bushi”. Later, they were taken over by street performers who sang the songs while selling copies of their texts. This article takes as its subject popular songs beginning with soshi-bushi and continuing through to the beginning of the Showa period (late 1920's to early 1930's), when recordings of these songs began to be made commercially.At first, enka played an extra-musical role in catching the attention of the populace to transmit to them the message of the democratic movement. For this reason it lacked any fixed musical form. It possessed, rather, a musical transcience and topicality, in that it freely set texts about any event that captured common attention to music that happened to be popular at the time, such as minshingaku (Chinese music of the Ming and Qing dynasties), shoka (songs in Western style used in education), Asakusa Opera and the like. Anticipating the preferences of the masses, enka reflected their contemporary attitudes towards music, and were widely appreciated by them.In this research, 280 songs verified from among those actually identified as enka have been listed according to the chronological order in which they were popular, and each song has been transcribed and analysed. As a result, it has become possible to divide the period from 1888 to 1932 into three sections. These are: a) the first period, 1888-1903, centring on a group of related pieces using traditional techniques, based on “Dainamaitobushi”

2 0 0 0 OA ジェンダーと音楽学

- 著者

- 井上 貴子

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1997, no.62, pp.21-38,L2, 1997-08-20 (Released:2010-02-25)

The purpose of this paper is to explore how one can apply the recent advances in gender theory to musicology, concentrating on concerns about feminist criticism and the historicizing of gender. I will use the post-structuralistic concept of gender, because I believe that this is a rigorous approach to theorizing gender and most effectively avoids ghettoization. This approach also transcends historical periods, areas and genre boundaries.Gender theory has been the most important concept for feminists, rallying many people to join the debate. Feminists have asserted that the subjective identity of men/women is a social and cultural construction. The wide acceptance of this conceptualization, however, has led to social and cultural determinism: producing descriptive accounts of gender roles as a static dichotomic order ruled by the inherent logic of a certain society or period, supporting the idea of cultural relativism. In the case of musicology, feminist musicologists who attempted to reestablish women as the subject, have discovered women composers and musicians who have been ignored or concealed by leading musicologists. It is at this moment important that women studies are not relegated to a marginal and supplemental sphere which would serve to reify the existing belief of unequal gender relations based on biological differences.To surmount such a static dichotomy, the strategic theory must be made based on the issues raised by feminism. In the larger field of art, linguistic and visual representations such as literatures, paintings, films, performances and so on, which can give concrete images of women, have drawn attention, but music has received much less. This might be due to the existence of strong belief in the autonomy of music because of the lack of concreteness in sound. Recent studies, however, have made it clear that music, which has been the last stronghold of autonomous art, is greatly influenced by ideologies and the larger societies. Without dispelling such a belief and recognizing the politics of art —any type of power related to the construction and practice of meanings in a society—, gender theory can not be effectively applied to musicology.In an important development, feminist criticism has been applied to music. The most specific feature of musicology might be the ability of analyzing musical sound itself as well as notations, visualized texts of music. Feminist music criticism tries to explicate how meanings of musical sound are constructed: the process of articulating musical discourses through gendered discourses. Susan McCraly, the most well-known musicologist in this field, starts by rejecting the idea of autonomous art and then tries to bring to light the idea that music and its processes operate within the larger political arena. She analyzes not only worded music such as opera but also absolute music.We should recognize gender issues raised by feminists are related to men as well as women: men as the transcendental or universal subject in a patriarchal society now become the mere male subject. Gender music criticism including feminist music criticism, has already started to be developed.History of women apparently seems to acquire a certain status, considering the numerous books and articles that have been recently published. Have the leading historians indeed neglected it as having nothing to do with economic and political history? Such a phenomenon is called ghettoization. As a strategy for surmounting this, the theory submitted by Joan W. Scott has inspired many scholars. She regards the historicizing of gender as the explicating the ways of producing the meanings of gender in different contexts; the exposing the concealed power relation through paying attention to the politics of constructing meanings.When her theory is applied to writing history of music,