1 0 0 0 IR 江陵鳳凰山漢簡再考

- 著者

- 佐原 康夫

- 出版者

- 東洋史研究會

- 雑誌

- 東洋史研究 (ISSN:03869059)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.61, no.3, pp.405-432, 2002-12

Many tombs from the age of the emperors Wen and Ying of the early period of the Former Han throughout the Fenghuang-shan 鳳凰山 area of the Jiangling District of Hubei Province 湖北省江陵縣 were investigated from 1973 to 1975. Within several of the excavated tombs organic objects such as wooden and woven artifacts had been particularly well preserved by the effects of ground water. Furthermore, lists of furnishings 遣策,were also excavated from several of the tombs, and the objects listed there in can be checked against the existing furnishings. This study aims at a comprehensive interpretation of the Han-dynasty wooden slips 簡牘 excavated from theses tombs. In general the slips excavated from Han-era tombs can be categorized as either funerary documents or those that are not. The former are intimately linked with the burial ceremony itself, including letters addressed to the officials of the underworld designed to assist the deceased in addition to the list of funerary objects. The latter were often written by the deceased in his or her lifetime, varied in content, and displayed little ceremonial character. My analysis of the funerary documents proceeds on the basis of this categorization. First, the following points may be specified on the basis of a comparison of the items in the list of furnishings with the many wooden figurines among the furnishings buried m the Fenghuang-shan tombs in Jiangling. In short, each and every of these wooden figurines had a personal name written on the list and had been placed in the tomb to serve the deceased as a slave. Among them can be seen various occupations, carriage drivers, outriders, chamberlains, domestic and farm laborers, but these are idealized version of a wealthy household. As the deceased journeyed off to the world of the afterlife with his household possessions including his slaves, he sometimes carried letters addressed to the officials of the underworld. This kind of funerary document was composed separately from the list of furnishings and displays specific characteristics according to period and region. Next, I examine the slips that recounted the life of the deceased. In the wooden slips excavated from Tomb No. Ten at Fenghuang-shan in Jiangling, one sees various items related to the collection of land rents, hay, and head taxes as well as commercial activities, revealing that the deceased was a village chief, lizheng 里正. Based on this evidence, one can analyze the role of the village chief and the character of his village. First, the residents of the villages of Shiyang 市陽里 and Dangli 當利里 in the Xixiang 西鄉 of Jiangling were of the farming class, but their area of cultivation was very small, and it appears that they had to depend on other methods to make a living. In this regard, these villages were communities with an urban character, unlike the typical Han village. The village chief who was buried in Tomb No. Ten had been charged with parceling out corvee labor assignments and the collection of land rents, hay and the head tax and its payment to the county 鄉 authorities. This variety of public service was carried out under direct order of the county, but itis thought that in practice the village chief was granted great latitude in fulfilling his duties. The village chief regulated the burden of corvee labor and taxes within his village and at times in cooperation with neighboring villages, in order to satisfy the demands of the government. Therefore the Han village can be regarded as one sort of social community that was complementary to the govemental administration. The wooden slips from the Fenghuang-shan in Jiangling strongly reflect the period of emperors Wen through Ying and the regional flavor of Nanjun 南郡 Jiangling District. Although they are historical materials related to the history of the Han-dynastic system, they cannot easily be generalized to provide a comprehensive interpretation. Nevertheless, their most outstanding character is that they provide a vertical section of a society from the poor peasant on the land to the wealthy in the underworld of a particular period and place.

- 著者

- 佐原 康夫

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

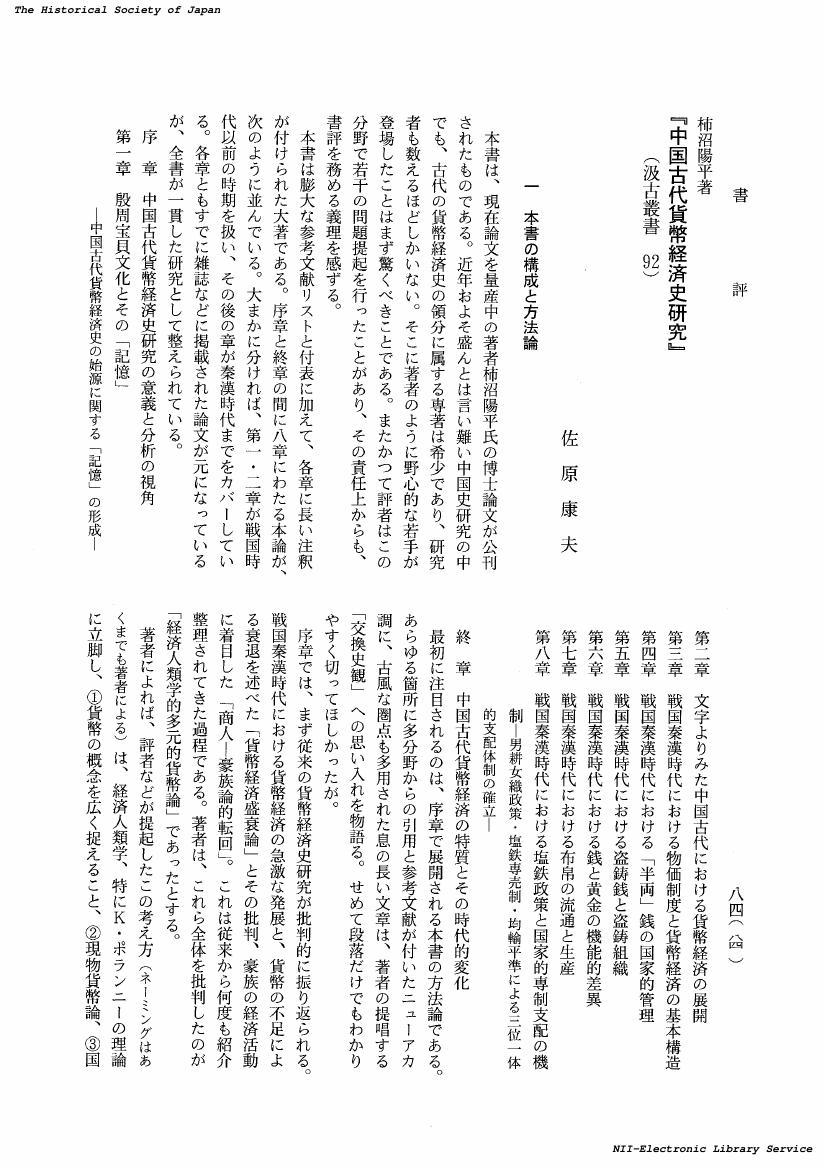

- vol.121, no.1, pp.84-90, 2012-01-20 (Released:2017-12-01)

- 著者

- 佐原 康夫

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.121, no.1, pp.84-90, 2012

1 0 0 0 IR 戰國諸子の士論と漢初の社會

- 著者

- 佐原 康夫

- 出版者

- 東洋史研究会

- 雑誌

- 東洋史研究 (ISSN:03869059)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.71, no.4, pp.619-645, 2013-03

1 0 0 0 IR 戰國諸子の士論と漢初の社會

- 著者

- 佐原 康夫

- 出版者

- 東洋史研究会

- 雑誌

- 東洋史研究 (ISSN:03869059)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.71, no.4, pp.619-645, 2013-03

In the fourth century BCE, politic reform in various states, beginning with the reforms of Shang Yang, was carried out, and the formation of bureaucratic despotic states progressed. In this process, the social character of the shi 士, who were to become leading figures in the next historical period, changed greatly. The scholars of the Hundred Schools of Thought, who treated the Mengzi as a classic, assembled many disciples who sought official posts as shi and traveled through many states expounding their theories in order to become active reformers of state policy. However, the idealized government bureaucratic structures organized to systematically select and train high-level bureaucrats with advanced decision-making and governing skills did not yet exist. Powerful figures and rulers, who competed to attract shi, and the shi who struggled to overcome difficult realities to become government officials developed a mutually supportive relationship and triggered an unrealistic vogue for righteous shi, yishi 義士, chiefly in the cities. With this historical period as a backdrop, in regard to the question, posed under the rubric of "experiencing insult and not feeling shame" 見侮不辱, whether one should retaliate violently when shamed, personal retaliation was in fact recognized as a valid act for the shi. This signifies that there existed in the society of the time a private sphere of justice which the rule of law could not reach. In the society in which the rule of law was based on popular sentiment and overflowed with violent activity, the worlds of the shi and the chivalrous ruffians, renxia 任俠, often overlapped. In local society that was subdivided into prefectural units, influential figures, such as local despots, hao li 豪吏, and the chivalrous ruffians, were entangled in the most intimate level of local rule. It can be surmised that the warlords, qunxiong 群雄, of the late Qin and early Han also obtained power premised on the basis of this political structure.

1 0 0 0 IR 文学部における初年次導入教育へのとりくみ

- 著者

- 佐原 康夫 山辺 規子 成瀬 九実

- 出版者

- 奈良女子大学

- 雑誌

- 奈良女子大学文学部研究教育年報 (ISSN:13499882)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1, pp.5-10, 2005-03-31