1 0 0 0 OA パネルディスカッション1「翻刻の未来」概要

- 著者

- 川平 敏文

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.101, pp.49-58, 2015 (Released:2017-04-28)

1 0 0 0 OA 『当世敵討武道穐寝覚』成立考

- 著者

- 川元 ひとみ

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.62, pp.13-27, 1995 (Released:2017-04-28)

1 0 0 0 OA 馬琴の吉凶観 ―『後の為乃記』を中心に―

- 著者

- 黄 智暉

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.85, pp.45-59, 2007 (Released:2017-04-28)

1 0 0 0 OA 近松と『愈愚随筆』 ―和製類書の介在―

- 著者

- 神谷 勝広

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.67, pp.24-32, 1998 (Released:2017-04-28)

1 0 0 0 OA 古松軒の林子平批判

- 著者

- 板坂 耀子

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.31, pp.20-30, 1979 (Released:2017-04-28)

1 0 0 0 OA 薄雪物語板本考

- 著者

- 松原 秀江

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.27.28, pp.48-64, 1977 (Released:2017-04-28)

1 0 0 0 OA 「助六所縁江戸桜」考 ―上演史からみた「ゆかり」の意味―

- 著者

- 齊藤 千恵

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.95, pp.1-14, 2012 (Released:2017-04-28)

1 0 0 0 OA 『月氷奇縁』の成立

- 著者

- 大高 洋司

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.25.26, pp.35-49, 1976 (Released:2017-04-28)

1 0 0 0 樵夫横尾時陰:―『英草紙』第三篇再考―

- 著者

- 木越 秀子

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.91, pp.44-56, 2010

1 0 0 0 賀茂真淵と田安宗武:―有職故実研究をめぐって―

- 著者

- 高松 亮太

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.114, pp.17-30, 2021

The aim of this paper is to explore the cultural significance of the collaboration of Kamo-no-Mabuchi and Tayasu-Munetake in the study of "yūsoku-kojitsu" or usages and practices of the ancient court and the samurai class. Referring to his other writings, postscripts, and marginal notes, here I chronologically trace Mabuchi's progress in research to foreground the important role played by Munetake in the study. Indeed their collaboration affected Mabuchi's study of classical literature as is typically seen in <i>Genji-monogarari-shinshaku</i>. Finally it is pointed out that Mabuchi and Munetake worked together on "yūsoku-kojitsu" in the historical context of reconciliation between the imperial court and the Tokugawa shogunate.

1 0 0 0 OA 実録『播磨国書写敵討』の成立 ―地方実録の創作方法の一事例―

- 著者

- 土居 文人

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.74, pp.13-25, 2001 (Released:2017-04-28)

1 0 0 0 OA 『南総里見八犬伝』と聖徳太子伝

- 著者

- 湯浅 佳子

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.71, pp.40-49, 2000 (Released:2017-04-28)

1 0 0 0 『椿説弓張月』の七五調

- 著者

- 野口 隆

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.72, pp.29-40, 2000

1 0 0 0 近世歌風史論序説:―十八世紀から十九世紀へ―

- 著者

- 浅田 徹

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.112, pp.55-67, 2020

Fujitani-Nariakira and Banbayashi-Mitsuhira, the "kokugaku" scholars of the Edo Period, divided the history of the styles of early modern <i>waka</i> poetry into two periods. While <i>Sangyoku-shū</i> established an elegant and ethereal style of poetry from the Muromachi Period to the late eighteenth century, the plain style of <i>Ruidai-fukugyoku-shū</i> became more dominant in the nineteenth century. In the eighteenth century the Jige poetical circles were explosively on the rise. Under the influence of the Dōjō school they usually referred to <i>Shin-dairin-waka-shū</i> and other poetry collections of the school which were modeled after the works of Emperor Go-Mizunoo's circle. In this way the trend of eighteenth-century poetics was created through the publishing media. In the nineteenth century, however, the school's ambiguous tone became out of fashion. Instead, as the number of lay poets was on the increase, the Jige school developed its own plain style more suitable for topics from their daily life. This is the goal of early modern poetics.

1 0 0 0 決断をめぐる物語:―『武家義理物語』の再評価へ―

- 著者

- 井上 泰至

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.104, pp.57-69, 2016

<i>Buke-giri-monogatari</i>, a collection of tragicomical episodes about samurai ethics, is acclaimed for its psychological insight but unfortunately quite unpopular. Why do we think it uninteresting and how can we enjoy reading it? If we find the collection rather boring, it is because we fail to appreciate Ihara-Saikaku's thrilling touch with which each episode is elaborated. Moreover for further appreciation we need to learn the habitus of the samurai class from such primary sources as <i>Oritaku-shiba-no-ki</i> and other diaries by samurai warriors as well as from historical documents of Japanese chivalry. In other words, we must try to re-live a samurai life to have the pleasure of reading the narratives, all of which culminate in the act of decision-making entailed by "giri" or feudal obligations.

1 0 0 0 OA 山々亭有人ノート

- 著者

- 興津 要

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2, pp.23-35, 1955 (Released:2017-04-28)

1 0 0 0 OA 「おこよ源三郎」説話について

- 著者

- 今岡 謙太郎

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.57, pp.37-47, 1993 (Released:2017-04-28)

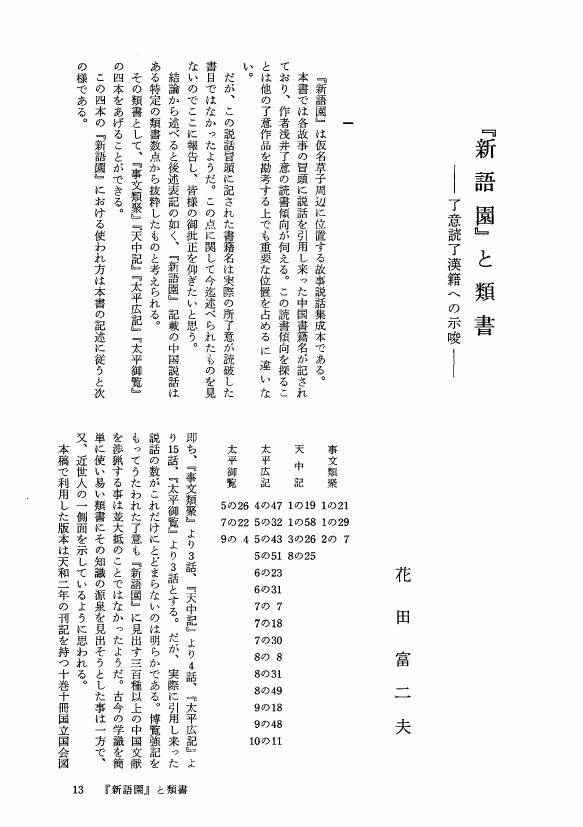

1 0 0 0 OA 『新語園』と類書 ―了意読了漢籍への示唆―

- 著者

- 花田 富二夫

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.34, pp.13-38, 1981 (Released:2017-04-28)

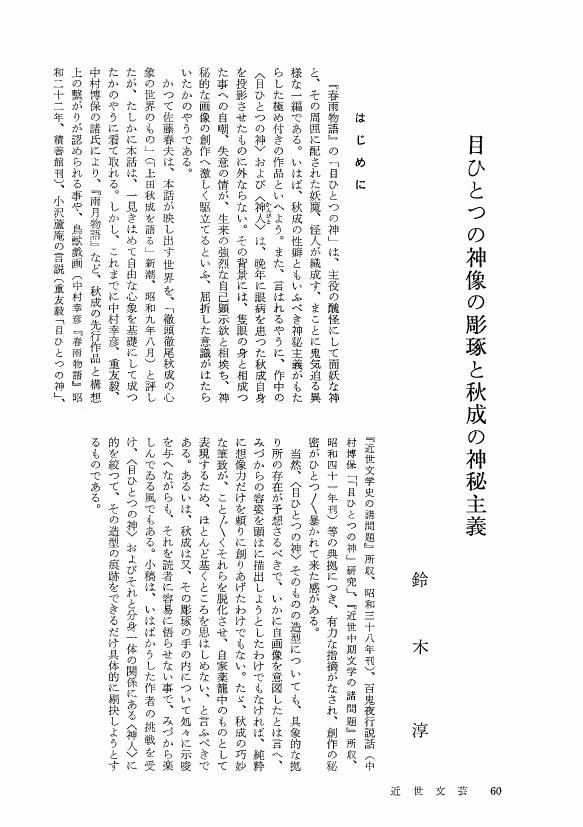

1 0 0 0 OA 目ひとつの神像の彫琢と秋成の神秘主義

- 著者

- 鈴木 淳

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.35, pp.60-70, 1981 (Released:2017-04-28)

1 0 0 0 OA 近世における曾我物語の軍談について

- 著者

- 浜田 啓介

- 出版者

- 日本近世文学会

- 雑誌

- 近世文藝 (ISSN:03873412)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.49, pp.1-20, 1988 (Released:2017-04-28)