1 0 0 0 OA 建設的民族論のために : 名和克郎氏の批判に応える

- 著者

- 綾部 恒雄

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.58, no.1, pp.88-93, 1993-06-30 (Released:2018-03-27)

1 0 0 0 OA 障害の文化分析 : 日本文化における『盲目のパラドクス』

- 著者

- 杉野 昭博

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.54, no.4, pp.439-463, 1990-03-30 (Released:2018-03-27)

本論の目的は「障害」についての文化分析の視点を検討することである。まず第一に, この視点の成立経緯をたどることによりその特徴を明らかにし, 次にこの視点から従来の日本の障害研究を批判的に検討することによってこの視点の意義が明らかにされる。さらに縁起や説話を題材としてそこに見出される盲目あるいは盲人の表象形態を日本における盲人文化としてとらえ, これに文化分析を適用する。つづけてこれらの盲人文化を担った日本の伝統的盲人職能集団の社会的性格に考察をすすめ, 「障害」を社会的=文化的コンテクストの中で全体的にとらえることにより「障害」を抱摂する社会の<民俗福祉文化>を明らかにする人類学的アプローチの可能性が検討される。結論としてゴフマンのスティグマ論について批判的検討が加えられる。

1 0 0 0 OA 「肉の政治学」 : サダン・トラジャの死者祭宴

- 著者

- 山下 晋司

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.44, no.1, pp.1-33, 1979-06-30 (Released:2018-03-27)

The people of the Sa'dan Toraja, the southern branch of the mountain people ("Toraja") in Central Sulawesi of Indoncsia, often say, "We live to die." An anthropologist who studies their society would understand that these words carry crucial implications. The ritual of the dead is their central concern and every effort during life is directed toward death. They accumulate wealth to spend it almost all on the occasion of death. The people who live as members of Toraja society cannot abandon this custom, because the obligation to hold a ritual for the deceased and to participate in the rituals for the relatives or neighbours forms an essential part of their own identity. Even the villagers who have been converted to Christianity or received modern education cannot despise these conventions. If they neglect this "old-fashioned and "irrational" practice they will lose their position in the village community. Thus it may not be an exaggeration to say that their society revolves around "death". This paper aims first to describe the death ritual of the Sa'dan Toraja in detail and, second, to discuss several important problems it contains, based on the data collected during my field research from September 1976 unti January 1978. Although the economy is now founded upon wet rice cultivation in the beautifully terraced fields on the mountain slopes at 800 to 1, 600 meters above sea level, the culture of the Sa'dan Toraja shows striking features of the swidden cultivators in Southeast Asia, that is to say, feasts with the sacrifice of cocks, pigs and water buffaloes, the erection of megaliths, head hunting practices, the use of ship motifs and so on. In particular their death ritual has much in common with the "feast of merit" as it is found among the upland peoples of mainland Southeast Asia. This fact leads me to the assumption that the death ritual of the Sa'dan Toraja is a kind of transformation or developed form of "feast of merit" with pompous stage-setting and elaborate arrangement which is attained by the increase of wealth through the introduction of wet rice cultivation. Therefore, it seems to me more relevant to call their ritual of the dead "death feast", the "feast of merit' on the occasion of death. The death feast is strictly ranked, according to their custom. The rank and scale of the feast, measured by the amount of sacrificed water buffaloes and the main feast, which is counted by the day, depends upon the social rank and wealth of the deceased and his family. In the death feast named dirapa'i, the highest rank, scores of water buffaloes and more than one hundred pigs are consumed for the period of the feast that covers in total one or more years. In the "autocratic" southern villages of the regency of Toraja Land it is the threefold division of social classes the nobles or chief class (puang) , commoners (to makaka) and "slaves" (kaunan) that plays an important role in determining which rank of the feast to hold. Thus, the wealthy noble or the man of the chief class hopes, or is required, to hold a great feast of high rank, because the funeral ceremony gives him the opportunity to reaffirm his socio-political status or rather promote his prestige in his village community. In order to give the full picture of the death feast in the Sa'dan Toraja, the argument of this paper is presented through three main stages of discussion. The theme in each stage is as follows: (1) examination of the ritual categories of the Sa'dan Toraja, (2) a case study on a death feast, and (3) the presentation of some important problems which the death feast contains.

1 0 0 0 OA 第 14 回 日本人類学会・日本民族学協会連合大会

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.23, no.4, pp.343-347, 1959-11-25 (Released:2018-03-27)

- 著者

- 今村 豊 池田 次郎

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.14, no.4, pp.311-318, 1950 (Released:2018-03-27)

According to Dr. Kiyono, the modern Japanese are the result of physical change, having developed out of a prehistortc type, through a protohistoric intermediate type, with some Korean admixture. The Ainu, being different from the peoples either of prehistoric or protohistoric periods, had nothing to do with the formation of the modern Japanese. These conclusions are said to be derived, with statistical procedures, from a survey of skeletons of all those periods. Thus, if there were defects in his chronology of skeletons and his anthropometrical methods, his conclusions would be questionable. In the first place, because of insufficient description of the excavations and the relation to other relics excavated, the chronology of skeletons is ambiguous. Furthermore, several errors can be pointed out. In the second place, there are defects in his anthropometric methods. When measurements are compared, the characteristics compared are not always of the same kind, and therefore the basis of comparison fluctuates. The "mittlere Typendifferenz" is calculated only between the most convenient materials, and general conclusions are drawn in spite of the fact that the interrelations between all materials have not been exhaustively worked out. On the basis of Dr. Kiyono's own anthropometrical data, the reviewers have calculated the "Typendiffirenz" between all materials exhaustively, and reached the following results : 1) Though Dr. Kiyono concludes that the difference between the modern Japanese and their adjacent peoples is greater than that between local types of the modern Japanese, his evidence, especially with reference to the relation of the modern Japanese to the Koreans and Northern Chinese, cannot be validated. 2) On the basis of Dr. Kiyono's anthropometrical data, the Ainu, rather than the protohistoric Japanese, would more probably be regarded as the intermediate type between the modern Japanese and the prehistoric people. 3) Statistical evidence as to the mixture with the Koreans is lacking. In short, even provided that the chronology of materials were exact, it would be impossible to draw Dr. Kiyono's own conclusions from his own statistics.

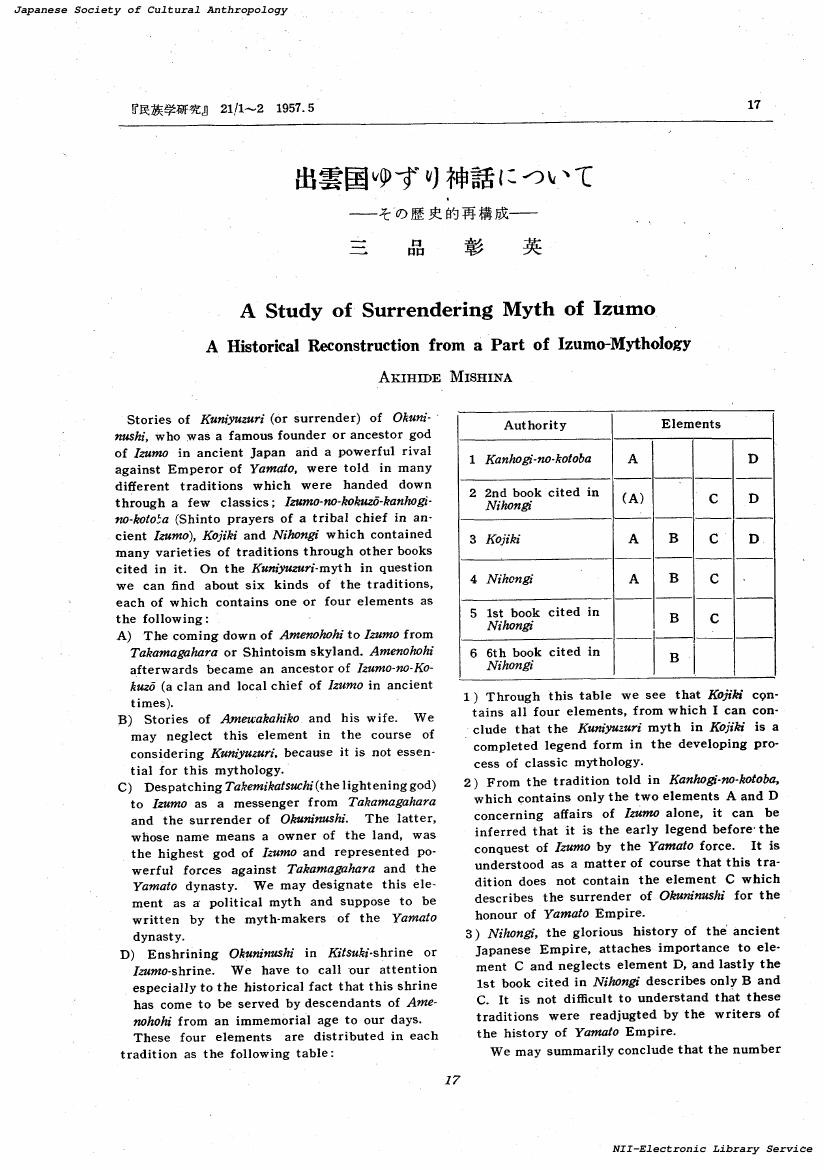

1 0 0 0 OA 出雲国ゆずり神話について : その歴史的再構成

- 著者

- 三品 彰英

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.21, no.1-2, pp.17-23, 1957-05-30 (Released:2018-03-27)

- 著者

- 池田 不二男

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.31, no.4, pp.292-293, 1967-03-31 (Released:2018-03-27)

- 著者

- 松園 万亀雄

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.32, no.3, pp.243-245, 1967-12-31 (Released:2018-03-27)

1 0 0 0 OA 北海道アイヌの葬制 : 沙流アイヌを中心として

- 著者

- 久保寺 逸彦

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.20, no.1-2, pp.1-35, 1956-08-10 (Released:2018-03-27)

1 0 0 0 OA 日本における育児様式の研究 : 長野県村の育児様式に就いて(修士・博士論文要約)

- 著者

- 須江 ひろ子

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.24, no.3, pp.267-274, 1960-09-05 (Released:2018-03-27)

1 0 0 0 OA ジェンダーからセクシャリティへ : イタリアの性に関する考察の試み

- 著者

- 宇田川 妙子

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.57, no.4, pp.411-436, 1993-03-30 (Released:2018-03-27)

フェミニスト人類学は,現在,多様な専門分化を遂げてきた反面,ある行き詰まりの状態にあるとも言われている。筆者は,その原因の一つとして,これまでそこで論じられてきた女性が,結局,社会的な意味での女性,即ち,ジェンダーとしての女性でしかなかったということに注目してみたい。性とは,ただ社会的な問題としてあるだけではない。男女の対面的な場,即ちセクシャリティの場で認識される男性および女性という問題もあり,それは社会的な場面での性差にも密接に係わっている。特にイタリアの文化社会における性の問題を考えるためには,この視点が必要となる。彼等は,性の本質を常に対面的な男女の関係が作り出す二元性として捉えている。つまり,彼等にとって性とは,基本的にセクシャリティなのである。それゆえ本稿では,イタリアにおけるこのような性のあり方を具体的に明らかにしてきながら,同時に,それを,フェミニスト人類学一般に対する新たな方向性を模索する試みとしても提示していく。

- 著者

- 丸川 仁夫

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.New1, no.10, pp.1009-1013, 1943-10-05 (Released:2018-03-27)

1 0 0 0 OA 沖縄における生理用品の変遷 : モノ・身体・意識の関係性を探る研究にむけて

- 著者

- 塩月 亮子

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.59, no.4, pp.464-469, 1995 (Released:2018-03-27)

1 0 0 0 OA 拂込票

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.6, no.3, pp.App2, 1940-11-10 (Released:2018-03-27)

1 0 0 0 OA 日本農村地域における「屋号」研究の可能性

- 著者

- 玉野井 麻利子

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.49, no.4, pp.343-351, 1985-03-31 (Released:2018-03-27)

1 0 0 0 OA ウェスターマークの訃

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.6, no.2, pp.303-304, 1940-07-20 (Released:2018-03-27)

1 0 0 0 OA Toan Anh, Tin Nguong Viet-Nam, ヴェトナム信仰, Vol.I, 475pp., Vol.II, 451pp., 380V.N., $ Saigon, 1968

- 著者

- 森 幹男

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.35, no.3, pp.239-240, 1970-12-31 (Released:2018-03-27)