4 0 0 0 OA 財産保有形体としてのワクフ:「自己受益ワクフ」の理論と実態

- 著者

- 五十嵐 大介

- 出版者

- 東洋文庫

- 雑誌

- 東洋学報 = The Toyo Gakuho (ISSN:03869067)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.91, no.1, pp.75-102, 2009-06

During the Mamluk period, powerful figures, especially the Mamluk military aristocracy, began to convert their private property into waqfs (Islamic religious endowments) for the purpose of securing the endowers’ private sources of revenue. The growth of the so-called “self-benefiting” waqf, that is、 a waqf earmarked for the endowers themselves as the main beneficiaries of the revenue earned from the waqf, reflected such circumstances. This article attempts to show the realities behind the “self-benefiting waqf,” examining 1) the ways by which endowers could include themselves as waqf’s beneficiaries, 2) the social stratum of such endowers, 3) the size of the waqfs in question, and 4) stipulations providing for beneficiaries after the death of the endowers contained in waqf deeds.Theoretically, the three schools of Islamic law, except the Hanafi school, denied the legitimacy of the “self-benefiting waqf,” however, in reality, the practice became widespread in both Mamluk Egypt and Syria. There were three methods by which waqf endowers could include themselves as beneficiaries. The first was to expend all earnings from the waqf’s assets on the endower himself; the second was to expend the surplus from waqf earnings after expenditures on the maintenance of waqf-financed religious or educational institutions, salaries and other compensation for the staff, etc; and the third was to divide waqf earnings between the endower and his charitable activities.Among the three methods, the first was the most popular, no doubt because it was a way by which the endower could benefit most directly from his waqf. In this ease, anyone who donated his private property as waqf, which involved the abandonment of all rights of ownership over it, could, nevertheless, continue to oversee the endowed property and pay himself compensation as the waqf’s controller (nazir). It can be said that there was no change in the de facto relationship between the property and its “ex”-owner before and after the endowment was made. In short, the “self-benefiting waqf” of this type could be seen as a way of securing the actual “possession” of one’s estate against such emergency circumstances as sudden political upheavals, sudden death by natural disaster, outbreak of war, or political intrigue, situations under which the subsequent confiscation of property could have occurred at any moment.

3 0 0 0 IR マムルーク体制とワクフ--イクター制衰退期の軍人支配の構造

- 著者

- 五十嵐 大介

- 出版者

- 東洋史研究会

- 雑誌

- 東洋史研究 (ISSN:03869059)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.66, no.3, pp.505-475, 2007-12

With the implementation of the highly systematic and well organized Iqta system, which depended on the completion of the cadastral survey (1313-25), referred to as al-rawk al-Nasiri, in Mamluk ruled Egypt and Syria (1250-1517), the Mamluk state and political system were constructed on this foundation. In this manner, the regimes of foreign military rulers, which were based on the Iqta system, which had been developed in the Arab-Muslim world since the latter half of the tenth century, reached an apex in the highly systematized Mamluk regime. As the fundamental land system of the period, the Iqta system served as the axis of political, military and governmental systems and formed the system that was the core of the ruling structure in which the Mamluks, who comprised the ruling class, controlled rural areas through possession of the Iqta lands and thereby held a grip on the supply of food, public works, economic and religious activities of the cities through the redistribution of the wealth obtained from the rural areas, and this influence reached throughout the entire society. However, the rapid expansion of the amount of land designated as waqf (religious endowment) following the latter half of the fourteenth century had a great influence on the Mamluk regime. This was not limited to the fact that due to the transformation of the state's land (amlak bayt ai-mal) into the waqf, the amount of land that could be distributed for the Iqta's was decreased and the economic foundation of the Mamluks continued to shrink. The increasing importance of the waqf, which was fundamentally independent from state control, as a self-regulating system for the redistribution of wealth that linked the cities and rural areas is thought to be link to the problem of relativizing and reduction of the social role of the Iqta system. From this point of view, I employ narrative and archival sources in this study to consider the sudden expansion of the waqf, whose social role from the late fourteenth century to the early sixteenth century in Egypt and Syria reached a stage that could not be ignored, the influence of the expansion of the waqf on the Mamluk regime, and amidst these factors, how the Mamluk military ruling class maintained the ruling structure, particularly in regard to the economic aspect. As a result, I make clear that they were involved at various levels in the waqf system as donators and beneficiaries, as administrators, and as leaseholders of waqf land, and thereby they were able to obtain wealth and social influence and were also able to maintain the Mamluk regime of ruling structure by incorporating the waqf system within it.

2 0 0 0 OA マムルーク體制とワクフ--イクター制衰退期の軍人支配の構造

- 著者

- 五十嵐 大介

- 出版者

- 東洋史研究会

- 雑誌

- 東洋史研究 (ISSN:03869059)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.66, no.3, pp.505-475, 2007-12

With the implementation of the highly systematic and well organized Iqta system, which depended on the completion of the cadastral survey (1313-25), referred to as al-rawk al-Nasiri, in Mamluk ruled Egypt and Syria (1250-1517), the Mamluk state and political system were constructed on this foundation. In this manner, the regimes of foreign military rulers, which were based on the Iqta system, which had been developed in the Arab-Muslim world since the latter half of the tenth century, reached an apex in the highly systematized Mamluk regime. As the fundamental land system of the period, the Iqta system served as the axis of political, military and governmental systems and formed the system that was the core of the ruling structure in which the Mamluks, who comprised the ruling class, controlled rural areas through possession of the Iqta lands and thereby held a grip on the supply of food, public works, economic and religious activities of the cities through the redistribution of the wealth obtained from the rural areas, and this influence reached throughout the entire society. However, the rapid expansion of the amount of land designated as waqf (religious endowment) following the latter half of the fourteenth century had a great influence on the Mamluk regime. This was not limited to the fact that due to the transformation of the state's land (amlak bayt ai-mal) into the waqf, the amount of land that could be distributed for the Iqta's was decreased and the economic foundation of the Mamluks continued to shrink. The increasing importance of the waqf, which was fundamentally independent from state control, as a self-regulating system for the redistribution of wealth that linked the cities and rural areas is thought to be link to the problem of relativizing and reduction of the social role of the Iqta system. From this point of view, I employ narrative and archival sources in this study to consider the sudden expansion of the waqf, whose social role from the late fourteenth century to the early sixteenth century in Egypt and Syria reached a stage that could not be ignored, the influence of the expansion of the waqf on the Mamluk regime, and amidst these factors, how the Mamluk military ruling class maintained the ruling structure, particularly in regard to the economic aspect. As a result, I make clear that they were involved at various levels in the waqf system as donators and beneficiaries, as administrators, and as leaseholders of waqf land, and thereby they were able to obtain wealth and social influence and were also able to maintain the Mamluk regime of ruling structure by incorporating the waqf system within it.

2 0 0 0 IR 原典研究 イブン・ハルドゥーン自伝(8)

- 著者

- ハルドゥーン イブン 中村 妙子 柳谷 あゆみ 佐藤 健太郎 五十嵐 大介

- 出版者

- 早稲田大学イスラーム地域研究機構

- 雑誌

- イスラーム地域研究ジャーナル (ISSN:1883597X)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.8, pp.64-91, 2016

- 著者

- 五十嵐 大介

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.118, no.12, pp.2180-2181, 2009-12-20 (Released:2017-12-01)

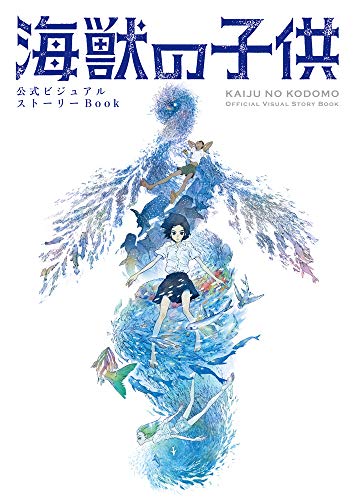

1 0 0 0 海獣の子供 : 公式ビジュアルストーリーBook

- 著者

- 五十嵐大介原作 「海獣の子供」製作委員会アニメーション製作

- 出版者

- 小学館

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 2019