11 0 0 0 OA ロールズを非理想化する 修正された第一原理の制度化に向けて

- 著者

- 福間 聡

- 出版者

- 東北哲学会

- 雑誌

- 東北哲学会年報 (ISSN:09139354)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.39, pp.65-87, 2023 (Released:2023-05-19)

8 0 0 0 IR 「死者に鞭打つ」ことは可能か--死者に対する危害に関する一考察

- 著者

- 福間 聡

- 出版者

- 東京大学大学院人文社会系研究科

- 雑誌

- 死生学研究 (ISSN:18826024)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.12, pp.149-129, 2009-10

There is a Japanese expression "whipping the dead." This derives from a historical event in China. Wu Zixu, whose father and brothers had been killed by King Ping of Chu, exhumed the dead body of the King from his tomb and whipped it three hundred times as a kind of revenge. In Japan, this expression became an idiom that refers to when we blame and attack the antemonem words and deeds of the deceased. We use this idiom to teach that we have to refrain from blaming the deceased if it diminishes his or her memory; for example, "Because the professor has already died, you should not blame his remarks in his later years. This is because you whip the dead if you blame him." Why should we care about the deceased in this way? Do we harm the dead by blaming them now? Can we harm a person who has already died? Ifwe can, what harm is it ?<改行> To begin with, in order that a person can receive profit or injury from an event, he or she must exist when it happens. That is, if "the Existence Condition" nothing bad can happen to a person unless he or she exists at that time - is valid, no harm will be caused to the dead. However, does not this conclusion contradict our intuition that even the dead can be subjected to the negative effects of our actions ? It seems that we generally think that we should avoid condemning the deceased's antemonem words, deeds, and achievements. Then, does the precept that we should not blame the dead imply that we should not blame a person (though he or she is living) who is presently absent? That is, do we think of it as proper etiquette that we should not blame a person who cannot argue against us? Or, do we think that we should not out of consideration for the bereaved family ?<改行> However, the reason that it is important for the absent living to argue against condemning him or her is that there are real interests that he or she wants to protect. But there are no such interests for the deceased because he or she now is not a subject who can have them. So the reason that it is impossible to rebut blame is begging the question in the case of the deceased if the Existence Condition is valid. Moreover, if the bereaved family and related parties are now non-existent, can we be permitted to deliver any blame on the deceased? If so, do we need not respect the wishes of the deceased who has no relatives at all ? <改行> In order to defend our intuition, there are two ways in which we can insist that people can receive harm and profit from events that happen posthumously. One way is that we can argue that some interests of the deceased can survive his or her death, and their fulfillment being obstmcted harms the antemortem person. The other is that we can argue that, because the will of the deceased does not continue to exist in the mode of interests, he or she cannot undergo "real change" by posthumous events-but can undergo a "Cambridge change (relational change)." <改行> In this article, through examining these two standpoints, I consider whether our (Japanese) intuition that we should not condemn the deceased and that we should respect the living will of the deceased is valid from the perspective of the philosophy of death. Then, in light of these considerations, I make a proposal on some of the issues surrounding organ transplantation in Japanese society. I insist that we cannot harm the deceased, but can wrong him or her.

4 0 0 0 OA 「真正な」善・悪はどこにあるのか?―道徳を教育するという視座から―

- 著者

- 福間 聡

- 出版者

- 国士舘大学哲学会

- 雑誌

- 国士舘哲学 (ISSN:13432389)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.17, 2013-03

2 0 0 0 OA 自己所有権から自己所有へ ―二つの能力概念の差異に基づいた転換―

- 著者

- 福間 聡

- 出版者

- 日本イギリス哲学会

- 雑誌

- イギリス哲学研究 (ISSN:03877450)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.24, pp.49-62, 2001-03-20 (Released:2018-04-25)

- 参考文献数

- 25

This article focuses on sell-ownership and articulates it. Libertarians insist that my person is my property, and I have exclusive rights to determine the course of its use and disposal, and further to enjoy full income gained by its use. But self-ownership is an obscure conception inasmuch as the very concept of person and the legal concept of property in themselves allow for varied interpretations. Through examining what a person is, and by noting our abilities, I divide them into two concepts, which may be called ‘intrinsic ability’ and ‘extrinsic one’. According to this division, in order to redefine self-ownership, I argue that we claim only the ‘right to integrity of person’ to the intrinsic ability, and ‘control right and restricted income right’ to extrinsic ability.

2 0 0 0 IR ロールズによるアリストテレス批判の変遷について : 差異と共通性についての探求

- 著者

- 福間 聡 Satoshi Fukuma 高崎経済大学地域系策学部

- 出版者

- 高崎経済大学地域政策学会

- 雑誌

- 地域政策研究 (ISSN:13443666)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.22, no.2, pp.15-30, 2019-12

2 0 0 0 IR 国家の正統性について : ロールズ的な視座から (地域科学研究所発足記念号)

- 著者

- 福間 聡

- 出版者

- 高崎経済大学

- 雑誌

- 産業研究 : 高崎経済大学地域科学研究所紀要 : bulletin of the Institute of Regional Science (ISSN:09155996)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.51, no.1, pp.55-70, 2016-03-25

1 0 0 0 OA 書評

- 著者

- 福間 聡

- 出版者

- 東北哲学会

- 雑誌

- 東北哲学会年報 (ISSN:09139354)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.23, pp.105-106, 2007-05-10 (Released:2018-02-28)

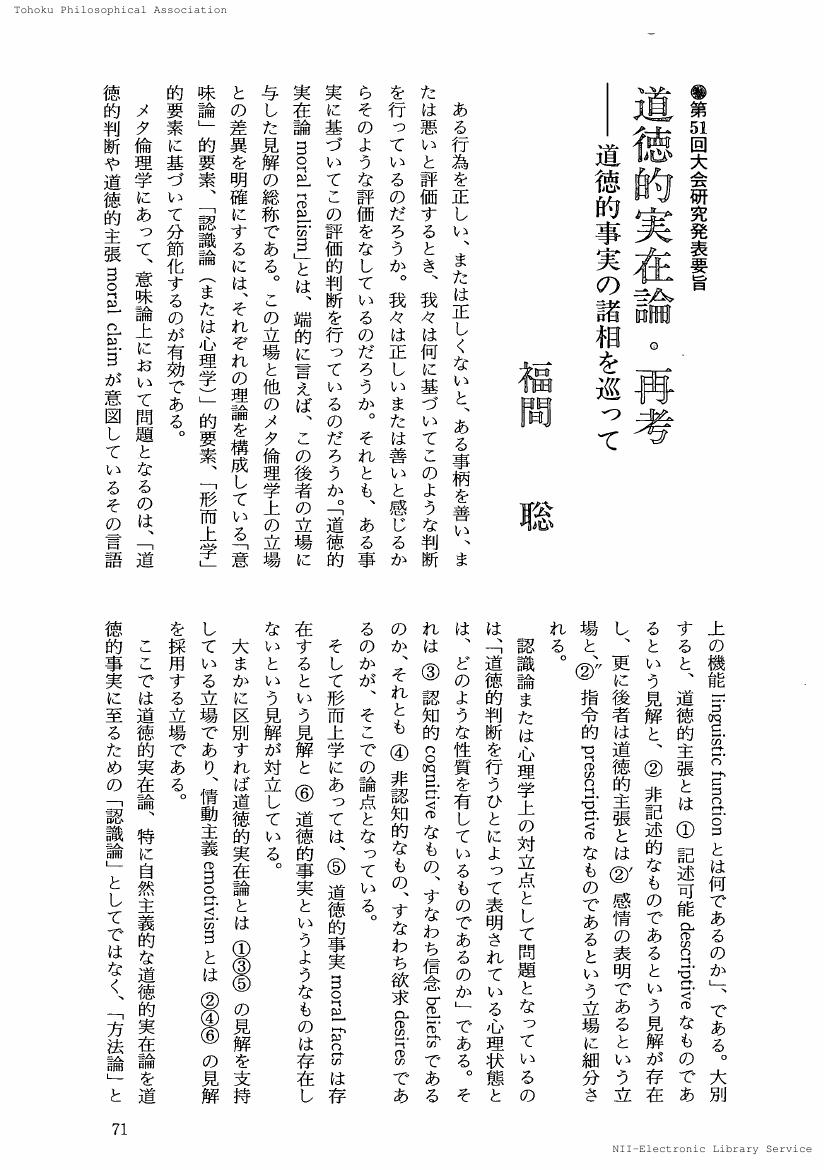

1 0 0 0 OA 道徳的実在論・再考 : 道徳的事実の諸相を巡って(第51回大会研究発表要旨)

- 著者

- 福間 聡

- 出版者

- 東北哲学会

- 雑誌

- 東北哲学会年報 (ISSN:09139354)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.18, pp.71-72, 2002-04-30 (Released:2018-02-28)

- 著者

- 福間 聡

- 出版者

- 理想社

- 雑誌

- 理想 (ISSN:03873250)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.685, pp.85-98, 2010

1 0 0 0 IR 人生の意味と幸福 : 労働の終わりにおいて

- 著者

- 福間 聡 Satoshi Fukuma 高崎経済大学地域政策学部

- 出版者

- 高崎経済大学地域政策学会

- 雑誌

- 地域政策研究 (ISSN:13443666)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.20, no.1, pp.15-33, 2017-08

1 0 0 0 OA 道徳的価値の規範性 構成主義に基づく一解釈

- 著者

- 福間 聡

- 出版者

- 日本哲学会

- 雑誌

- 哲学 (ISSN:03873358)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2008, no.59, pp.293-308,L22, 2008-04-01 (Released:2010-07-01)

- 参考文献数

- 15

Constructivism can usefully be seen as a view about normativity. It denies both that normativity is a constraint based on a fact which is prior to and independent of our stance (realism), and also that it is a merely causation originating in our conative attitudes (noncognitivism). It takes normativity to be a requirement which is derived from our rational choices and which is constructed by our practical reason. On this constructivist view, it becomes clear that normativity is constitutive of those who ‘are agents who make choices and judgments on the basis of reasons’. In this article, by examining moral judgments about the good from the viewpoint of Korsgaard's constructivism, I consider how it explains the normativity of moral value, and how it presents a possible means of dissolving the controversy between realism and non-cognitivism about moral value. First of all, I clearly specify what it is to be constructivist (sec. 2). Secondly, through examining a constructivist criticism of realism (sec. 3-4) and the rationalist theory about the good which constructivism advocates (sec. 5), I show that an important feature of the constructivist account of the normativity of moral value is that it emphasizes the procedure of making moral judgments in the light of our multiple agency. Thirdly, I set out what it is to be a reason-a concept which constructivism presupposes (sec. 6). Lastly, I reply to some objections to constructivism (sec. 7). In this article, I particularly take up G. E. Moore's realism and investigate onstructivism's explanation of normativity by contrast with this.

1 0 0 0 OA 「死者に鞭打つ」ことは可能か : 死者に対する危害に関する一考察

- 著者

- 福間 聡

- 出版者

- 東京大学大学院人文社会系研究科

- 雑誌

- 死生学研究 (ISSN:18826024)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.12, 2009-10-31

There is a Japanese expression "whipping the dead." This derives from a historical event in China. Wu Zixu, whose father and brothers had been killed by King Ping of Chu, exhumed the dead body of the King from his tomb and whipped it three hundred times as a kind of revenge. In Japan, this expression became an idiom that refers to when we blame and attack the antemonem words and deeds of the deceased. We use this idiom to teach that we have to refrain from blaming the deceased if it diminishes his or her memory; for example, "Because the professor has already died, you should not blame his remarks in his later years. This is because you whip the dead if you blame him." Why should we care about the deceased in this way? Do we harm the dead by blaming them now? Can we harm a person who has already died? Ifwe can, what harm is it ?<改行> To begin with, in order that a person can receive profit or injury from an event, he or she must exist when it happens. That is, if "the Existence Condition" nothing bad can happen to a person unless he or she exists at that time - is valid, no harm will be caused to the dead. However, does not this conclusion contradict our intuition that even the dead can be subjected to the negative effects of our actions ? It seems that we generally think that we should avoid condemning the deceased's antemonem words, deeds, and achievements. Then, does the precept that we should not blame the dead imply that we should not blame a person (though he or she is living) who is presently absent? That is, do we think of it as proper etiquette that we should not blame a person who cannot argue against us? Or, do we think that we should not out of consideration for the bereaved family ?<改行> However, the reason that it is important for the absent living to argue against condemning him or her is that there are real interests that he or she wants to protect. But there are no such interests for the deceased because he or she now is not a subject who can have them. So the reason that it is impossible to rebut blame is begging the question in the case of the deceased if the Existence Condition is valid. Moreover, if the bereaved family and related parties are now non-existent, can we be permitted to deliver any blame on the deceased? If so, do we need not respect the wishes of the deceased who has no relatives at all ? <改行> In order to defend our intuition, there are two ways in which we can insist that people can receive harm and profit from events that happen posthumously. One way is that we can argue that some interests of the deceased can survive his or her death, and their fulfillment being obstmcted harms the antemortem person. The other is that we can argue that, because the will of the deceased does not continue to exist in the mode of interests, he or she cannot undergo "real change" by posthumous events-but can undergo a "Cambridge change (relational change)." <改行> In this article, through examining these two standpoints, I consider whether our (Japanese) intuition that we should not condemn the deceased and that we should respect the living will of the deceased is valid from the perspective of the philosophy of death. Then, in light of these considerations, I make a proposal on some of the issues surrounding organ transplantation in Japanese society. I insist that we cannot harm the deceased, but can wrong him or her.

1 0 0 0 OA 社会正義と善き生死 : 社会正義を支持するさらなる理由としての健康と善き死

- 著者

- 福間 聡

- 出版者

- 東京大学グローバルCOEプログラム「死生学の展開と組織化」

- 雑誌

- 死生学研究 (ISSN:18826024)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.10, 2008-09-30

講演