2 0 0 0 OA ゴルギアス篇におけるプラトンの意図

- 著者

- 加来 彰俊

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典學研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.8, pp.28-42, 1960-03-29

What was the aim of Plato when he wrote his dialogue Gorgias? -It is the objective of my present article to clarify that aim of his by examining both the construction and content of that dialogue. First, as regards the construction of the dialogue, the questions we deal with here are as follows : What is the true theme of that work? How is the dialogue of three acts unified organically? To attain this unification, how are the interlocutors arranged and directed by the author? Next, as for the content, our problems are : How should we understand the difference of the criticism toward the rhetoric given in the Gorgias from that given in the Phaedrus? What is the real meaning of Plato's statement that Socrates is a politician in the true sense of the word? From my research made from the above viewpoints results the following conclusion concerning Plato's aim now at issue. In this dialogue Plato makes clear that he has given up ultimately his political ambition which has been cherished from his philosophical way of life which Socrates taught him. I. e. this work is Plato's so-called 'manifesto', in which he proclaims his conversion from politics to philosophy. Now Plato's criticism toward the actual politics at the time was founded upon Socrates' doctrine and way of life. It is really in this dialogue that he verifies. the validity of those words and deeds of Socrates reviewing them and thereby offers an apology for his master again, and at the same time he uses it as such for his own new life as well. Thus it is that we could call this dialogue the second 'Apologia Socratis' -nay, we should rather call it "Apologia Platonis (s. pro vita sua) " as its more appropriate byname. Having found the principle of the ideal politics in Socrates' philosophy, he has come to postulate that famous thesis in this dialogue for the first time, the thesis of the identification of philosophy with politics, which is afterwards to. be developed in the Respublica and the Epistula VII.

2 0 0 0 OA ヘラクレイトスの魂論 : 断片36における魂概念の生理学的解釈をめぐって

- 著者

- 木原 志乃

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典学研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.50, pp.12-23, 2002-03-05 (Released:2017-05-23)

In this paper, I would like to examine the change of the soul (psyche) in fr 36 and reconsider the significance of Heraclitus explaining the soul in the physical process In fr 36, Heraclitus says that the soul becomes the water, the water becomes the earth and vice versa There is little agreement as to what the changes of the soul should be It is a disputable question whether the reciprocal changes in fr 36 are in macrocosm (that is, the extinction or production of the soul from its relation to the sea and the earth cf fr 30 and 31) or in microcosm (that is, the physiological process of the soul from its relation to the blood and the flesh) Many commentators have interpreted it as being in macrocosm However, I do not share this interpretation First, I will examine the two typical interpretations in which the soul in macrocosm is supposed (Kirk and Kahn) According to Kirk, the soul is equated with cosmic fire and 'the death of the soul' means the death of individuals in an eschatological context However, this interpretation is unsound when Kirk must suppose the relation of two fires, between 'a fiery soul' of individuals and the 'cosmic fire' Although Herachtus indicated 'the soul out of water', Kirk discounted this point and supposed falsely the soul out of cosmic fire through respiration On the other hand, Kahn intended that the soul is equated with the air Inasmuch as Heraclitus described the soul as 'dry' or 'wet', so Kahn considered that 'fire' is not suitable as a substitute for the soul from the expressive viewpoint in the fragments Although Kahn's interpretation is a correct one in view of his insistence that the soul is not fire, he overcomplicated the relation between the 'airy soul' of individuals and (cosmic) fire or water The soul as the fire or the air, which is also macrocosmic, is not suitable for the explanation of 'the death of the soul' The important point is the relationship between life and death We must recognize that, for Helaclitus, the psyche has the fundamental meaning of 'life force' and that his 'life and death' is a unity of opposites Heraclitus did not uncritically accede to antecedent ideas of the soul The traditional problem of immortality is reconsidered by Heraclitus in fr 36 The 'death of the soul' is not the biological death of the individual Rather, his use of the soul enables him to combine these aspects of the life and death of individual I would like to emphasize this point and elucidate that the soul includes death and is incessantly renewed as life by death Heraclitus refused the traditional idea that the soul of individuals continues separate from the body after death For him, the soul is not a transcendental substance separate from the body, but constantly maintains the material aspects of the bodily force So for Heraclitus the soul is not like an airy or fiery element or a cosmic soul, but the constitutive principle of the life force That is the meaning of the physiological process This suggests that the soul in fr 36 is a principle for physiological activity as the subject of the life force Finally, I wish to conclude by referring briefly to two connected contents of the soul, as a subject of this physiological activity and of the cognitive activity in other fragments.

2 0 0 0 OA セネカの時代における政治と権力(シンポジウム「セネカとその時代」)

- 著者

- 島田 誠

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典学研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.56, pp.102-106, 2008-03-05 (Released:2017-05-23)

2 0 0 0 ノモスとロゴス : 『クリトン』のソクラテスを中心に

- 著者

- 内山 勝利

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典学研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.29, pp.41-52, 1981

The main purpose of this paper is to reconsider the true standpoint of Socrates in the Crito, one of the earlier dialogues of Plato, in order to remove misunderstandings about the Socratic attitude towards the city-state and the law. This attempt will at the same time clarify the substantial principle which is constantly held by Socrates throughout his life and death. From ancient times, it has been frequently considered that Socrates in the Crito puts the law of the city-state into the position of the absolute standard of ethical judgment. A series of discussions on this problem has recently again arisen from the papers of R. Martin("Socr. on Disob. to the Law", Rev. of Metaph., 24/1970, 21-38)and of A. D. Woozley("Socr. on Disob. the Law", G. Vlastos ed., Philos. of Socr., 1971, 299-318). Many of the writers debate it on the assumption that the central point of the assertion here stated by Socrates lies in the 'Destruction of the City' argument(so named by G. Young, whose paper in Phronesis 19/1974 is also referred to particularly in my paper) , whether they agree with or reject it. But, the author thinks, when we read the Crito following carefully the essential structure of the argument which is, as is explicitly stated at 48E-49E, already systematically methodised, and that in the same way as is formalised in the Phaedo, then it will become obvious that the 'Destruction of the City' argument is only a showy but untrue one, while Socrates' substantial assertion is stated duly with the 'hypothetical' procedure based exactly on the αρχαι(49D-E). The true reason for his refusal to escape is, accordingly, not because his escape might bring destruction of the law and then of the city-state, but just because it is not compatible with the αρχαι accepted by himself or, in other words, not compatible with "the logos which upon reflection appears to me to be the best"(46B). In short: when said in response to the subtitle to this dialogue, περι πρακτεου, it is asserted here by Socrates that we should make our conduct conform to the judgment of the logos, and not in obedience to the law.

- 著者

- 三浦 要

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会 = Classical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典学研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.50, pp.123-126, 2002

[書評]

2 0 0 0 OA アリストテレスの「第三の人間」論とイデア論批判

- 著者

- 牛田 徳子

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典学研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.31, pp.19-31, 1983-03-30 (Released:2017-05-23)

The most important locus classicus of the 'Third Man Argument' (TMA) in Corpus Aristotelicum is found in the Sophistici Elenchi(178b36-179a10). There the TMA, the last example of sophistical refutations depending on the form of expression, is said to presuppose the admission that the common predicate, like 'man', expresses, because of its form, just what is a 'this' (hoper tode ti), that is, the substantial essence of a being (e.g. Callias) , in spite of the very fact that it expresses a quality, a quantity or some one of the other non-substantial attributes. Depending on Alexander's report of the lost work De Ideis and on his comment on Metaphysics 991a2 ff. that the Platonic Form is a 'universal' essentially predicable of individuals, many scholars explain Aristotle's TMA as follows : that which produces the 'third man' is the individualisation of the universal predicate common to the essences of Form and of particulars. This interpretation has nothing to do with the TMA above in the Soph. El. which will then assert that 'the universal predicate common to the essences of Form and of particulars' does produce the 'third man' without the 'individualisation' of that predicate, for any universal expressing an attribute, once admitted that it expresses an essence, will produce something like a third essence. The TMA in the Soph. El. depending on the similar form of expression of things that are not categorially the same, can be elucidated by a passage from the Topics (103b27-39) which distinguishes two kinds of 'what-is-it' expressions, the intercategorial and the categorial. By the former, one can give the species-genus definition to whatever the given being is, e.g. man, white, a foot length, the latter two of which are not substances, while that definition does not express any categorial 'what-is-it' (the substantial essence), but a quality or a quantity or some one of the other attributes. The truth is then as follows. That which the Form and the particulars have in common is not the eidos qua substantial form, but the eidos qua species (Met. 1059a13) whose one logos is predicated both of the Form and of the particulars as synonymous entities, so that it is limited to setting forth differentiae -a sort of 'quality' {Met. 1020a34)- to the question "what is the species 'man'?", differentiae specific and generic ('biped', 'sensitive' and so on) which are valid to all individual members belonging to the species 'man', but not valid to a substance like Callias himself, endowed with the essence identical with himself. That which causes the TMA is, therefore, to assimilate the inter-categorial 'what-is-it' expression which is in fact an attributive expression, to the categorial 'what-is-it' expression which is, according to Aristotle, the only substantial expression. Aristotle's criticism of the theory of Forms, therefore, does not consist in the following: in spite of the fact that every universal expresses an attribute, the theory of Forms which makes it express the individual, should recognize not only the second being, but the third being both having the same essence as the sublunary beings, but in the following: because of the fact that every universal expresses an attribute, the theory of Forms making it express the essence should recognize not only the second, but the third being both having the same attribute as the sublunary beings. By the first formula of criticism one could be inclined to think that Aristotle purports to emphasize the idealistic character in the theory of Forms, while in the second to see Aristotle's tactics to make the Forms 'universalized attributes'-accidental phenomena-separated from the sublunary substances, which inverts the very relation of Paradeigmata of that world and eidola of this world.

- 著者

- 辻 佐保子

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典學研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.27, pp.68-82, 1979-03-29

Cet article fait partie d'une serie d'etudes consacrees au theme de la Resurrection du Christ, dont le premier article a ete deja, publie dans "Orient", XIII, 1977 ("Ce que l'iconographie des Saintes Femmes au Tombeau doit a l'art funeraire paien"). Dans ce second article, nous voulons examiner une representation fort originate et inome-vue du cote de l'art chretien-des trois personnages habilles en blanc qui s'evadent a, travers de deux portes entr'ouvertes, peintes en perspective et amenagees dans deux compartiments du cubiculum F de la nouvelle catacombe de Via Latina a Rome. La structure de ces ouvertures avec deux vantaux repliants et la presence de personnages au dessus de leurs seuils peuvent etre rapprochees de la representation semblable au decor d'interieur qu'on trouve souvent dans la peinture romano-campanienne. Mais, cette comparaison ne sufnt pas pour expliquer le geste precipite et l'expression d'etonnement que montrent nos trois personnages. L'un vu de dos, la jambe droite projetee en arriere, essaie d'ecarter les vantaux de la porte avec sa main droite et son epaule gauche. Deux autres se retournent un instant apres avoir traverse le seuil de la chambre funeraire. C'est surtout une serie de sarcophages, dite de "la porte d'Hades", recemment etudiee par B. Haarlov, y compris le celebre sarcophage de Velletri, qui nous aide a elucider la signification de ces personnages peu habituels. En effet, mise a part une simple porte sans figure humaine et en trois etats differents fermee, entr'ouverte ou brisee par force , on y trouve quelquesfois l'ombre du defunt ou des personnages mythologiques (Alcestis, Protesilaos) accompagnes des divinites psychopompes (Hercule, Hermes) , qui emergent de la porte entr'ouverte d'Hades. Une longue tradition iconographique depuis l'art etrusque nous montre que l'ouverture de la porte du tombeau signifie a la fois le depart vers le monde d'audela, et le retour a, la vie, la resurrection. Les ivoires paleochretiens autour de l'annee 400 ont adopte le meme motif de la porte en trois etats differents, pour le tombeau du Christ dans la scene des "Saintes Femmes au Tombeau" : elle est fermee dans l'ivoire de Munich, entr'ouverte dans celui de Milan et detruite dans celui de Londres. Surtout deux derniers etats doivent evoquer la sortie miraculeuse du Christ de son tombeau, a savoir une Resurrection par excellence qui garantie celle des chretiens en general. Mais dans tous les cas, la representation realiste, la resurrection corporelle du Christ est evitee. Elle n'apparait que plus tardivement sous l'influence des illustrations des Psaumes. Il est generalement admis que la representation de la resurrection des morts ne commence qu'a, partir du 9^e siecle-de meme que celle du Christ en corps-, et qu'elle est associee soit avecle "Crucifiement" (selon Mat. 27, 52), soit avec le "Jugement Dernier". Dans ces cas, les morts ressuscitent en deplacant les couvercles des sarcophages et ce n'est plus a travers de la porte de l'edifice ou de la chambre funeraire. Pourtant, le theme traditionnel de l'ouverture de la porte a ete utilise d'une autre maniere par ces artistes medievaux, a la fois pour l'iconographie de "l'Ascension" en tant que l'ouverture de la porte du Paradis (Adventus du rois de gloire, inspire par le psaume 23)et pour celle de la "Descente aux Limbes" en tant que la destruction de la porte d'Enfers. Nous reviendrons a ce probleme dans notre prochain article. Pour expliquer les gesticulations tres vives de nos trois personnages, nous avons essaye de les confronter avec quelques textes du Nouveau Testaments relatifs a la resurrection des morts, entre autres I Ep. Cor., IS, 51-52, qui insistent sur l'instantaneite("in momento in ictu oculi") de cette "transformation" du corruptible a l'incorruptible. Un des sermons prononce a la fete de Paques de Gregoire de Nazianz decrit longuement, en terme biologico-psychiatrique-qui evoque la scene du cours de l'anatomie decorant une des lunettes du cubiculum I de la meme catacombe-, cette resurrection instantanee et le retour subit de la memoire du passe a chaque homme. Ainsi, au son de la trompette, les trois morts ensevelis dans les trois arcosolia du cubiculum F ressuscitent instantanement. L'un se precipite vers la porte qui s'ouvre et deux autres, deja franchi le seuil, se retournent et regardent avec un air etonne l'interieur de la chambre qu'ils viennent de quitter. Bien que tres precoce, il doit s'agir ici d'une representation audacieuse de l'evasion de la chambre funeraire, c'est-a-dire la delivrance de la mort, utilisant le motif semblable a l'ouverture et a la sortie de la porte d'Hades, frequent sur les monuments funeraires paiiens d'un ou deux siecles anterieurs. D'ailleurs, Prudence, poete chretien contemporain influence par le vocabulaire de la litterature classique, ne dit-il pas qu' "apres le trepas, notre chair qui etait morte. Notre poussiere se rassemble en corps, et du tombeau renait notre forme d'autrefois" (Cathemerinon Liber, III, 193-95)?

- 著者

- 辻 直四郎 高津 春繁

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典学研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.3, pp.173-178, 1955

- 著者

- 脇本 由佳

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典學研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.45, pp.28-39, 1997-03-10

『イーリアス』においてアイネイアースは,トロイア方でヘクトールに次ぐ重要な英雄として扱われている.しかし,『イーリアス』の中でのアイネイアースの活躍は,意外なまでに少ない.本稿では,この矛盾を解決しうる一つの仮説を提示するべく,『イーリアス』におけるアイネイアースの描かれようを観察し,そこから,ホメーロス以前のトロイア伝承で,主にアイネイアースがどのような位置づけをなされていたかを探る試みを行う.

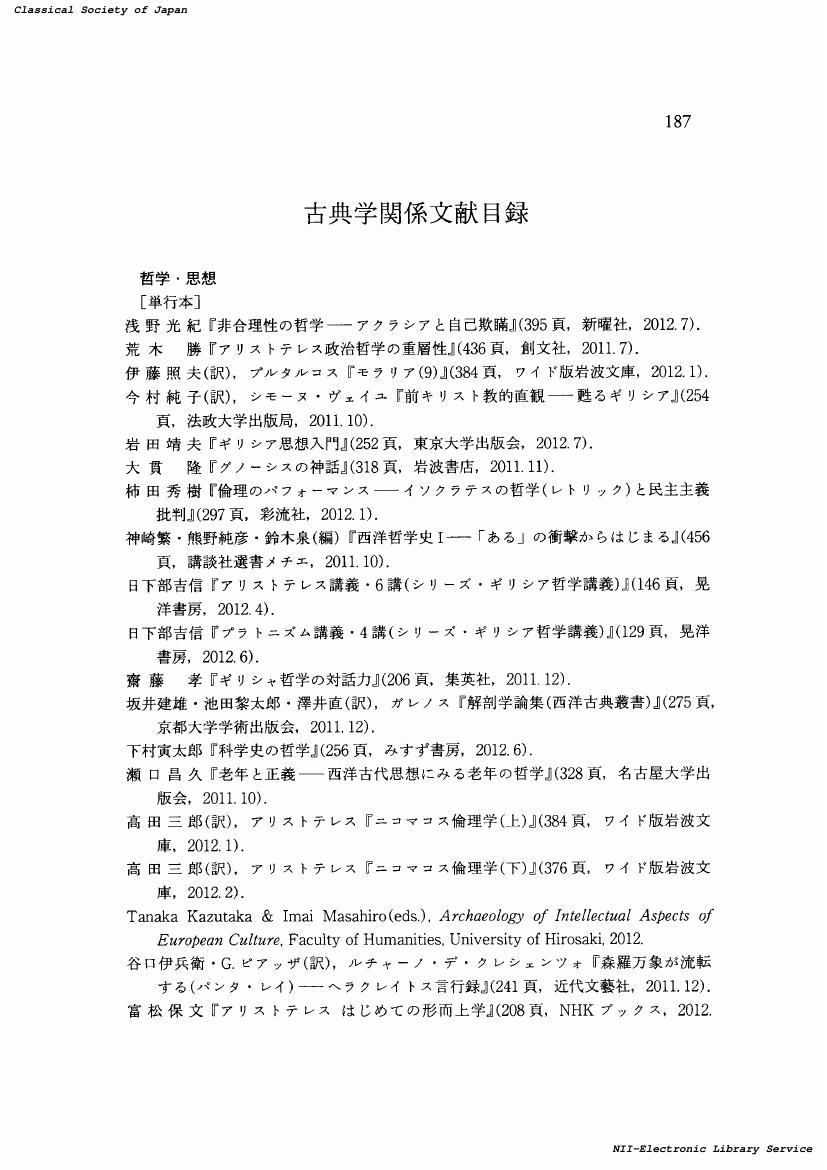

2 0 0 0 OA 古典学関係文献目録

- 著者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典学研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.63, pp.165-187, 2015 (Released:2018-03-30)

2 0 0 0 OA 古典学関係文献目録

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典学研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.61, pp.187-212, 2013-03-28 (Released:2017-05-23)

- 著者

- 脇本 由佳

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典学研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.45, pp.28-39, 1997-03-10 (Released:2017-05-23)

『イーリアス』においてアイネイアースは,トロイア方でヘクトールに次ぐ重要な英雄として扱われている.しかし,『イーリアス』の中でのアイネイアースの活躍は,意外なまでに少ない.本稿では,この矛盾を解決しうる一つの仮説を提示するべく,『イーリアス』におけるアイネイアースの描かれようを観察し,そこから,ホメーロス以前のトロイア伝承で,主にアイネイアースがどのような位置づけをなされていたかを探る試みを行う.

2 0 0 0 OA アリストテレス『政治学』第VIII巻の音楽論

- 著者

- 原 正幸

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典學研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.38, pp.51-60, 1990-03-29

Book VIII of the Politics is generally regarded as practical treatise on music education In fact, though, it is a theoretical treatise on music in which Aristotle attaches importance to two essential powers that music has, i e <<pleasure>> and <<influence upon the manner of dealing with (ethos) of soul>> His consideration of the former is based on his other discussions of pleasure, and that of the latter, on his theory of imitation First, he divides the ends of music into (i) amusement, i e relaxation, (ii) education, and (iii) action m the leisure as ultimate end He then compares (i) with (iii), bringing into relief the characteristic of the pleasure contained in (iii) Furthermore, he speaks of (ii) as preparatory training for (iii), in an attempt to illustrate the essentials of this pleasure Subsequently, he defines <<the pleasure as produced by the nature>> (i e activity of the sound faculty of hearing) to be common to all men He then picks up that which is suitable for the education of <<the habit of dealing with (arete)>> (i e moral virtue non-individuated) from <<the influence upon the manner of dealing with of soul>> which is inseparably connected with that pleasure, and applies it to music education by introducing his theory of imitation-according to which there is an immediate resemblance between <<the manner of dealing with of soul>> and the mele which imitate them The task of music education is to habituate the young to be able to judge correctly the beautiful mele, by using words analogically to describe <<the manner of dealing with>> in the actions It is this analogy between their two uses that is the very point which has been overlooked by traditional interpretations Although the <<correct judgement>> is impossible without the activity of the faculty of hearing, it is no more its activity, but that of <<the habit of dealing with>> (moral virtue non-individuated) And the enjoyment on the correct judgement is nothing but the pleasure which perfects this activity , so that two sorts of pleasures are contained in the use of music for the leisure as the ultimate end Therefore, it may be said that Aristotle does not only approve of the pleasure in music such that it is so (i e pleasure as produced by the nature), but also prescribes the one such that it should be so (i e pleasure as perfecting the activity of <<the habit of dealing with>>, and suggests to us the horizon where a community of souls could be established in music

2 0 0 0 OA レイトゥルギアの社会的意味 : メトイコイの関与の点から

- 著者

- 片山 洋子

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典學研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.18, pp.40-51, 1970-03-23

Since Boeckh pioneered in the study of liturgies in the nineteenth century, many works have been published on this subject. Yet except for incidental references, none of them have dealt thoroughly with the significance of the participation of metics in the liturgies. The liturgies originated in the period of the oligarchy and, in the democratic period, began to be performed not by noble families as in the earlier days but by wealthy citizens as honourable duties. A curious fact is that both citizens and non-citizens performed them in classical Athens where each category of population enjoyed a legal status distinct from the other. Here I want to discuss the problem of the participation of non-citizens in the liturgies and consider the significance of this fact. In the Panathenaic festival, metics performed a few fixed liturgies. Perhaps originally these accorded them honour; but, as the performer was restricted only to the metics who were humble in their social standing, the liturgies assigned to them also came to be looked upon as rather humble ones. Among the encyclic liturgies, we are certain that metics performed the choregia. However, they did so only in the Lenaean festival, which was held in winter, and for this reason they did not thrive. So the supposed honour may not have been held in common by both metics and citizens. Some scholars state that citizens alone performed the trierarchy but they do not enlarge any further upon this problem. However, as Kahrstedt has shown, the role of metics in the trierarchy was important. However, they did not become official trierarchs; there is a case of a metic embarking on behalf of a citizen trierarch. I think this cannot be the solitary example. Considering the original function of the trierarchy as a measure of naval defence substituting the naucracy, the embarkation was its most essential part. Nevertheless, in this case, a citizen trierarch bore only the financial part of his duties and transferred personal service required of him to a non-citizen. This is a parallel to the fact that citizens preferred to accept mercenaries in the army than to arm themselves. Apart from its importance in the scheme of national defence, the trierarchy had a secondary effect to promote its performers in society. The citizens wanted to monopolize the honour of bearing the title of litourgos. Therefore, when they allowed metics to take part in some liturgies, they restricted the latters' participation; when they entrusted metics the essential personal service in the trierarchy, they reserved the title of trierarch by bearing the financial part of his duties. This explains some passages in the writings of contemporaries as Aristotle, Demosthenes, Lysias etc., to the effect that, while the citizens maintained the position of litourgos to be an honourable one, in fact, they did not want to perform the liturgies by themselves, but only desired the position of litourgoi in order to win fame and they discharged the financial part of their duties for fear that they should harm their reputation by failing to perform the liturgies which they had undertaken. By the time of Aristotle, the liturgies had lost their original spirit and had become detached from their original purpose. However, as they were closely related to the democratic structure of Athenian society, they survived to the end of the democratic period.

2 0 0 0 OA 感覚と思考 : プラトン『テアイテトス』184b4-187a8の構造

- 著者

- 田坂 さつき

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典學研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.46, pp.22-32, 1998-03-23

In the last argument of the first part in the Theaetetus(184b4-187a8), Socrates tries to refute the first definition of knowledge that it is perception. In the argument he distinguishes between perception and consideration and argues that being(ουσια) belongs to consideration, but not to perception, and therefore that the definition is false, for whatever being does not belong to a being cannot be knowledge. According to the orthodox interpretation, Plato distinguishes between making judgement and having sense experience, and argues that in order to make any judgement one must grasp being, for every judgement has a propositional construction, which requires being as one of its constituents. But in sense experience, for example, in sight we see a colour of an object, but do not see a proposition that an object is coloured in such and such a way. So sense experience does not yield judgement. Hence it is not knowledge. But I cannot accept this interpretation, because it cannot explain why the arguments of the second part restrict kinds of judgement to identity. According to it, the conclusion of the last argument of the first part concludes that perception is not knowledge, but judgement can be knowledge. It follows that any kind of judgement can be a candidate for knowledge. But the argument of the second part deals only with identity judgements. So the orthodox interpretation cannot explain why they restrict kinds of judgement to identity ones. In my view, Plato does not distinguish between making judgement and having sense experience, but between considering basic comprehension in language about our experience and having sense experience. When Theaetetus agress that colour can be percieved through eyes and sound through ears(184c1-185a3), he considers that colour is one thing, sound is another, and that there are 'both things'(αμφοτερω)at once(cf. 185a4-10). Now Socrates analyzes the contents of Theaetetus' consideration in this way: (1) Theaetetus previously considers that there are both(sc. a colour and a sound) (185a8-10). (2) He considers that each of them is distinct from the other and the same as itself(185a11-b1). (3) He considers that both together are two, and each of them is one (185b2-3). (4) He can investigate whether they both are alike each other or unlike (185b4-6). Plato uses the expression 'being(εστον)' in (1), but not in (2)(3)(4) by ellipsis. Plato pays attention to (1). (1) is an assumption for Theaetetus' consideration of 'both things'. So the being(εστον) in (1) means an existential assumption, which is necessary to thinking or saying in language. Theaetetus' consideration of 'both things' is also expressed as the consideration that each is and each is not(cf. 185c5-6, c9). To avoid any jump of logic, the consideration that, for example, colour is colour, and colour is not sound. This is an identifying judgement. So the consideration of 'both things, is composed of four contents((1)〜(4)), namely an existential assumption ((1)), and two comparisons with each other((2), (4)) and calculation of number((3)). We can say, therefore, Plato uses 'being' in two senses, that is, the sense of existence and the sense of identity, in this passage, when we consider the basic comprehension about our experience. But the identifying judgement includes the existential assumption ((1)). Thus, if we don't consider 'both things' as comprehended above, we cannot intend to observe and describe each of them and say that an object is perceived to be in such and such a way. Therefore our experience, for example, perceiving, observing, saying, describing, etc., is based on this sort of comprehension in our mind. Therefore, according to my interpretation, it is reasonable to restrict kind of judgement to identity alone, in the argument of the second part. For it has shown that the last argument of the first part itself has already done so. It has the merit of being able to find out the logical connection between the two arguments without difficulty. Hence we must conclude that in the last argument of part 1 Plato dintinguishes between having experience and considering basic comprehension about our language

- 著者

- 桜井 万里子

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典学研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.58, pp.1-11, 2010

How prevalent were the Orphic mysteries in classical Athens? Important evidence for this question was discovered during the second half of the 20th century. In 1978 were published a set of bone tablets with graffiti-like letters of the fifth century BC. from Olbia. The Derveni Papyrus (DP) was found in 1962 from one of the tombs dated around the end of the fourth century near Derveni about twelve kilometers north of Thessaloniki, the editio princeps of which was published in 2006, almost fifty years after its discovery, as T. Kouremenos, G. M. Parassoglou and K. Tsantsanoglou, The Derveni Papyrus, Firenze, 2006. The editors date the papyrus between 340 and 320 BC, whereas the text itself on the papyrus is more difficult to date, but the content of the text is mostly supposed to suggest it is a Preplatonic commentary on the Orpheus theogony. A gold tablet from Hipponion in south Italy published in 1974 turned out to be from 400 BC., the oldest among the same kinds of tablets, and the words mystai and bakchoi in the text have convinced scholars of the Orphic religious significance of this and other gold tablets of the same type. Looking at the sites of the evidence on the map, we cannot suppress the impression that they are in marginal areas in the Greek world, or not in major poleis like Athens or Sparta. Were the Orphic Mysteries not popular in Athens? One paragraph on the deisidaimon in Theophrastos' Kharakteres, 16 persuaded me to assume private practice of the Mysteries by the orpheotelestai in Athens, but Plato's comment in the Republic 364d-e puzzled me as he wrote that agyrtai and manteis(orpheotelestai-like people) persuaded not only private individuals but some poleis. What did Plato mean by the word poleis ? Were there any poleis where the Orphic Mysteries were public ? Athens certainly could not be counted among such poleis. Col. XX of the Derveni Papyrus may help us attain a good understanding of how the Orphic Mysteries were performed in classical Athens. In this column two groups of initiates are contrasted: those who were initiated, participating in the public Mysteries, and those who were initiated in the Mysteries under the guidance of a private professional priest. The editors of the editio princeps of DP believe that both groups were meant to be initiates in the Orphic Mysteries, but I cannot agree with the editors' comment. I would like to propose my own opinion that the former are not initiates in the Orphic Mysteries but initiates in public mysteries like the Eleusinian Mysteries, while the latter are Orphic initiates. Col. XX may shed some light on the way in which the Orphic Mysteries were performed in Athens.

- 著者

- 蛭沼 寿雄

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典學研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.15, pp.165-168, 1967-03-23

2 0 0 0 OA アガメムノーンの「試み」 : B72-5

- 著者

- 松平 千秋

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典學研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.10, pp.39-48, 1962-03-31

At the beginning of the Iliad Bk 2, Zeus sends his messenger Dream to Agamemnon with the false message that, if the war should be resumed, the Greeks would beat the Trojans Agamemnon, determined to rearm his soldiers, summons, prior to the general assembly, a council of the leading generals, and requests their cooperation in carrying out his plan, which is summarized in ll 72-5 At the assembly, however, his plan proves to be a sheer failure, as soon as the proposal of retirement is made, the army rush to their camps to make preparations for their return home The confusion is so disastrous, that, but for Hera's intervention, the retirement of the Greek army would be realized 'contrary to fate' (υπερμορα) Evidently it is not Zeus but Agamemnon himself, who is responsible for this confusion, because the idea of "tempting" the soldiers was not involved in Zeus' plan How, then, does such a strange idea, which seems to serve only as a cause for troubles, occur to Agamemnon ? The present author thinks that the clue to the solution of this question is to be sought in ll 72-5 Let us start our discussion from the following two points (1) What is in this context the meaning of the phrase η θεμιζ εστι (73) ? (2) What is the object of ερητυειν (75) ? 1) After having examined several views set forth hitherto by modern critics, the author concludes that the scholiast's interpretation (Scholia A ad loc) best suits the context He says that the King tries to test the army κατα τι παλαιον εθοζ, with the intention of knowing whether they are going to fight voluntarily or reluctantly, compelled by force, for, the scholiast continues, the King knows that the Greeks had been discouraged by the long war, by the plague, and moreover by Achilles' withdrawal from the battle-line We do not know, it must be confessed, what precedents the poet had in mind when he said η θεμιζ εστι, i e κατα τι παλαιον εθοζ. We must assume, however, that there were examples so familiar to the poet and his audience alike that it was hardly necessary for the poet to add further comments on the topic We moderns could easily collect a dozen similar examples from various times and places 11) With regard to the second point, the author again takes sides with the ancient critic (Scholia B ad loc ), who takes sue (sc Agamemnon) ταυτα λεγοντα as the object of ερητυειν, not εκεινουζ (sc 'Αχαιουζ) φευγονταζ, as did Leaf et alii Interpreted on this line, Agamemnon's plan was to stage a sham fight between the chieftains and himself, and thus to lead the debate toward his intended conclusion It is true that his plan did not succeed at the first assembly, Agamemnon may be blamed for his miscalculation of the low morale of his army But let us here turn our attention to the reopened assembly, and we shall see how smoothly, after the Thersites-scene, of course, everything proceeds, almost (not exactly, indeed) as the King had intended Agamemnon had been no fool His plan, though checked for a while, proves a success after all Certainly there are some exaggerations in the narrative from Agamemnon's "Temptation" up to the "Thersites-scene" One may even call it a trick on the poet's part Probably the poet thought that a detailed narrative to such an extent was necessary in order to make the audience realize how low the army's morale was and how difficult a task it was to make this resume warfare But it must be admitted on the other hand that the emphasis, perhaps over-strong, on this aspect has mainly been responsible for causing various misunderstandings, especially among modern critics The present writer suggests that the Temptation passage including the Thersites-scene may be called a "detachable" part of the poem By "detachable" the author means no "interpolation" in the Analyst's sense, but rather a section which the rhapsode, at discretion, could have, if not entirely omitted, at least cut to the minimum The text of the Iliad, as well as the Odyssey, represents the fullest version of the poem, collated probably in Athens in the sixth century, as is generally assumed The recitation of the whole poem may have taken place occasionally, e g at the Panathenaic Festivals But surely in most cases, it was recited on a far smaller scale, and, on such occasions, it must have been the normal practice of the rhapsode, to skip over or to abreviate non-essential (episodic) parts of the story The present writer imagines that the Homeric poems were, at least before their text was finally established in Athens, in a rather fluid condition, so that the rhapsode was given a considerable liberty in handling the text This article is not intended, of course, to draw too broad a conclusion from a single passage of the Iliad, but the author does hope that this is at least one of those cases which justify more or less his own point of view on the nature of ancient Greek poetry

2 0 0 0 OA アリストテレスにおける感情と説得 : 『弁論術』における「聴き手に拠る説得」の内実

- 著者

- 野津 悌

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典學研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.50, pp.24-34, 2002-03-05

In Rhetoric 1 2 Aristotle says that artistic modes of persuasion are of three sorts, which he calls ethos, pathos, and logos, and he recommends all three modes However, among them pathos consists in arousing emotions, and in Rhetoric 1 1 he prohibits arousing emotions because it is not right to corrupt judgement This inconsistency between the first and second chapter of his treatise has been much discussed In this paper, I examine one prevailing explanation of the inconsistency, which one can find in E M Cope's Commentary, and with which other scholars, e g A Hellwig and J Sprute, agree According to this explanation Aristotle's statements in 1 1 concern only an ideal rhetoric, which can function only if an ideal system of laws exists which prohibits the litigants from speaking outside the subject, just like in the Areopagus, and he does not claim that under real circumstances of public life arousing emotions must be prohibited Therefore, it is not inconsistent that he prohibits arousing emotions on the one hand and recommends it on the other He regards it, so to speak, as a necessary evil under real circumstances, to be used for morally irreproachable ends But this explanation is not persuasive in that arousing emotions is regarded as corrupting the hearers' judgements, and yet allowable only if it is used, as a necessary evil, for morally right ends I argue that Aristotle regards arousing emotions not only as corrupting the hearers' judgements, but also as playing an important role in the hearers' recognition of the truth Then, in order to make clear the difference between the corrupting one and the other which enables hearers to recognize the truth, I reconsider what Aristotle means by saying in 1 1 that it is right to prohibit "speaking outside the subject" According to the above explanation, which supposes "speaking outside the subject" is identical with arousing emotions, Aristotle means that arousing emotions in itself must be prohibited But, in my view, that is not right "Speaking outside the subject" here is identical with, not arousing emotions m itself, but a corrupting kind of arousing emotions, namely, arousing emotions by means of speaking about things totally extraneous to the issue Aristotle means here that only arousing emotions in such a way must be prohibited According to this view, we can suppose, there is another kind of arousing emotions, which Aristotle does not prohibit, namely, arousing emotions by means of speaking about things which are related to the issue and so enable hearers to recognize the truth To conclude, I propose that the primary function of pathos which Aristotle recommends in 1 2 consists rather in making hearers recognize the truth than in corrupting their judgement Indeed it is undeniable that pathos in 1 2 can function also as a necessary evil, as the prevailing view has it, but I claim that it is rather a subsidiary function of pathos

2 0 0 0 OA エウセビオス『コンスタンティヌスの生涯』の諸問題 : その真正性,成立年代,編集意図

- 著者

- 保坂 高殿

- 出版者

- 日本西洋古典学会

- 雑誌

- 西洋古典學研究 (ISSN:04479114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.58, pp.60-73, 2010-03-24

The Vita Constantini(VC), an encomiastic biography containing fifteen imperial letters, is one of the most important and controversial sources on the reign and personality of Constantine the Great that the church of the post-Constantinian period ever produced. Although certain critics have sometimes questioned its Eusebian authorship, recent studies have made extensive use of the text as a reliable literary source, suggesting that the issue has been conclusively resolved. Indeed, serious debate on this matter ceased in the 1970s. However, a critical reading of the text of the VC reveals that there are marked discrepancies between its description of the religious policy of Constantine and the picture of religious policy painted by pagan literature and legal texts. Most scholars are aware of this, yet they try to explain these discrepancies away as interpolations, in order to preserve the traditional view concerning its authorship from challenge. Thus, it is possible to suggest the following: 1)The characteristics of an intolerant emperor as they appear in the VC should neither be attributed to the historical Constantine (who was in fact tolerant of pagan religious practices) nor considered as stemming from the hand of an anonymous interpolator, since this antipagan writing is permeated with subversive ideas which form its conceptual framework. The enmity towards the Roman cultural heritage should therefore be viewed as being a constituent part of the work-thereby precluding the possibility of interpolations or posthumous editorial additions. 2)The VC could have been written by anyone living during a period after the death of Eusebius when the emperor was enforcing an anti-pagan policy-that is, in the time of Constantius II or later. 3)The notion of eusebeia (piety)-generally indicating any pious act for the benefit of the gods-is extended in the VC to encompass a negative attitude towards the impious. Indeed, from the start of the third century onwards there are many recorded instances of pagan assaults on Christians as acts of expiation (for example, Tert Apol 41.2 Christianos ad leonem!). However, neither the church nor the government succumbed to the popular outcry, and it was not until the latter half of the fourth century that the notion of piety in the form of a double negation was conceived. Theodosius II prescribes punishment of religious dissidents as a holy sacrifice to secure divine favor (Novellae 3.8). 4)If the VC is assigned to the time of Constantius II, it could belong to the literary genre of specula principum (mirrors for princes)-that is, its purpose could be to instruct him on how to behave towards and rule his subjects (both pagans and Christians alike) and to caution him against interfering in the internal affairs of the church. However, assigning the VC to the era of the Theodosian dynasty would instead suggest that it was composed in reply to pagan criticism of Constantine's pro-Christian policy. This seems more probable, since it is only after the 370s that the approval of physical violence which characterizes the VC is clearly attested in Christian literature.