31 0 0 0 OA 抵抗権と抵抗義務について 日本国憲法に於ける抵抗権と抵抗義務

- 著者

- 田畑 忍

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1959, pp.67-89, 1960-09-25 (Released:2009-02-12)

- 参考文献数

- 23

26 0 0 0 OA 自由はリズタリアニズムを支持しない

- 著者

- 立岩 真也

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, pp.43-55,204, 2005-09-30 (Released:2008-11-17)

まず「報告要旨」として送った文章を再掲する。拙著『自由の平等』(岩波書店、二〇〇四年)に考えたことを書いた。第一章でリバタリアニズムに対する反駁を行っている。また、契約論的な理論構成からもリバタリアニズムが正当とする規則は導出されると限らず、導出されても規則の正当化に至らないことも述べた。また第二章では嫉妬や怨恨を持ち出して社会的分配を非難する論に対する反論を行い、そして第三章で私たちがどのような私たちであれば、分配はより積極的に支持されることになるのかを検討した。(第四章から第六章は社会的分配に肯定的なりベラリズムの議論の吟味なので、今回の議論には直接には関わらない。)この本は基本的には財の所有・分配について論じた本なのだが(それ以外のことを論じた本ではないのだが)、その範囲内については、基本的なところでは間違っていないことが述べられていると考えている。だから報告もその線に沿ったものになる。(関連情報はホームページhttp://www.arsvi.comをご覧いだだきたい。)「Aが作ったものをAが所持し処分することは認められるが、それをBがとることは認められないとされる。/しかしこれを自由の立場から正当化することはできない。『私が私のためのものをとる』という状態と自由とを等値する人、自由とつなげる人もいるが、それはただ単に誤解している。この状態で自由であるのはAであり、Bは自由ではない。Bはしたいことができない、自由を妨げられていると言いうる。この状態を是認する立場を「私有派」と呼ぶならそれは自由の立場ではない。」(pp. 40-41)つまり、所有・分配については、私の立場はリバタリアンの立場とはまったく異なっており、その立場は間違っていると考えている。ゆえに、以下に引用するその本の第一章の冒頭近くは、私としては比較的好意的な記述と言えるのかもしれない。「これは別に論ずることにするが、リバタリアンの主張にはおもしろい部分もある。おもしろいことも言う人たちがなぜこんなことを言うのか、不思議に思える。だから考えてみようとも思う。/まず、国家が行うことの性質を強制と捉えること自体はもちろん間違いではない。むしろ本質を捉えている。国家が他と異なるのは、それが強制力を持つことであり、リバタリアンはこのことにはっきりと焦点を当てている。だからその主張は検討するに値する。」(pp. 37-38)強制されることがさしあたり歓迎されざることであることを認めよう。また強制を介在させることに伴う厄介事が様々あることを認めよう-それをどのように軽減できるかを考えることは興味深く重要な主題である。しかし所有権を設定し保護する規則を設定するのであれば、それは強制であり、様々ありうる規則の違いは、強制の有無という違いではなく、どのような強制を行なうかの違いである。むろん、これと別に、ここに一切の規則を設定しないという選択肢 リバタリアンの中にもそれを支持する人は多くないように思うが-もある。しかしやはりこの場合でも、多くの人々は生きるに除去あるいは軽減することのできる制約を課せられることになる。それでよいかと考えると、やはり望ましくないと答えることになる。そして以下は、学会大会で私が述べたと記憶していることである。そこでなされたように思う議論の一部にもふれている。またすこし論点を補った部分もある。リバタリアンの言説は湿気ってなくて、それは私が好きなところだ。また、森村進の論などに存する一種の脱力感、妙な力が入っていないところも好きだ。このようにまず述べて、あるいは後で補足して、私は以下のようなことを述べたはずである。

24 0 0 0 OA 治安・司法の市場化-無政府資本主義について

- 著者

- アスキュー デイヴィッド

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1994, pp.37-53, 1995-10-30 (Released:2008-11-17)

- 参考文献数

- 12

19 0 0 0 OA リベラリズムとジェンダーのありか

- 著者

- 江原 由美子

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2003, pp.56-67,233, 2004-10-20 (Released:2008-11-17)

- 参考文献数

- 4

Following the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the communist regimes of the Eastern Bloc led to large changes in social theories. One of the changes was a revival of liberalism. Although liberalism was expected to solve social inequalities, it was also criticized because of its justification of social inequalities. This paper argues how liberalism could possibly justify gender-related inequalities. Firstly, I argue that the characteristic logic of liberalism could be described as universalism. Next, I make two arguments which explain how liberalism has excluded women; firstly, for historic sociopolitical reasons, and secondly, because of its universalist character.

18 0 0 0 OA アナルコ・セクシュアリズムをめざして

- 著者

- 住吉 雅美

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2003, pp.109-120,232, 2004-10-20 (Released:2008-11-17)

- 参考文献数

- 10

In this article, I argue that we should abandon the dualism of gender, male/female, and that we must recognize that gender is gradational. By so doing, it may benefit many sexual minorities (for example, homosexuals, transgenders, intersexuals, etc.) who are oppressed by the dualism of gender and hegemonic heterosexuality. A plan of this article is as follows: 1. I inquire into the causes of the dualism of gender and hegemonic heterosexuality in modern society. I deal with the causes as follows: (1) modern patriarchy and capitalism, (2) marriage system as means of reproduction, (3) restraints on our daily performance by gender, and so on. 2. I consider a theoretical framework for the reduction of that hegemony including: (1) identitypolitics, (2)“gender-performativity” (by J.Butler), (3) criticism of homophobia, (4) queer theory, and so on. 3. I consider the extent to which we can trust administration and legislation to construct “a sexually free society”. In conclusion, I argue that legal intervention in sexualities should be avoided as much as possible, and that sexual identity should be left to each individual.

16 0 0 0 OA 「性同一性障害者の性別の取扱いの特例に関する法律」立法過程に関する一考察

- 著者

- 谷口 功一

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2003, pp.212-220,226, 2004-10-20 (Released:2008-11-17)

- 参考文献数

- 20

On the 10th of July 2003, a bill cleared the Japanese Diet and was promulgated six days later ironically under the name and with the seal of the Emperor which is often said to represent the ‘patriarchal symbolic system’ of Japan. In defiance of the long-accepted idea that Parliament “can do everything except make a woman a man, or a man a woman”, this law enabled people with ‘gender identity disorder’ to legally change the sex registration on the family register (koseki). In this article we offer a brief description of this legislative process and a certain normative argument on it. Firstly, we examine the very concept of transgender, transsexual and gender identity disorder from medical and sociological viewpoints. In addition, the history and environment surrounding transgender in Japan is outlined here. Secondly, we take a look at the legislative process itself on its two phases formal and informal. The formal phase is concerned with the public/visible procedures mainly in the Diet, and the informal one with the ruling party's internal/nvisible examination. Standing on these analyses based on social and political reality, we go further to examine the contents of this law. Compared with similar laws in such countries as Sweden, Germany, Italy…, this new Japanese legislation is more severely termed, notably in that only people without children are allowed to change their registered sex. At the same time, the law contains a proviso that it is to be reviewed and opened to revision in 2007 (three years after its enforcement). Though legal philosophers have traditionally paid less attention both theoretically and practically to legislature than to judiciary, this epoch-making legislation and its process in Japan seem to offer us a meaningful insight into the former.

9 0 0 0 OA 憲法学において「自己決定権」をいうことの意昧

- 著者

- 佐藤 幸治

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1989, pp.76-99, 1990-08-25 (Released:2008-11-17)

- 参考文献数

- 40

9 0 0 0 OA 正義の「相対性」について

- 著者

- 稲垣 良典

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1966, pp.29-52, 1967-05-20 (Released:2009-02-12)

- 参考文献数

- 52

8 0 0 0 OA 法哲學における形而上學と經驗主義

7 0 0 0 OA 法時間論 法よる時間的秩序、法に内在する時間構造

- 著者

- 吉良 貴之

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2008, pp.132-139, 2009 (Released:2021-12-29)

The purpose of this essay is to examine the relation between law and time. At first, 'time by law' and 'time in law' should be distinguished. 'Time by law' is social time order constructed by law, and 'time in law' is internal time structure in law. The former is about role of law, and the latter is about structure of law. Law has time structure corresponding with its time role, and legitimacy of law consists of both kinds of time. Sense of time diverges in each person, but common time should be shared for social practice. Law is not the only instrument, but the most powerful one for construction of social time order. Predictability ensured by law enables us to make our life plans. If our memories conflict in legal practice, judge will determine which past should be regarded as true, by examining existing evidences of both sides, in the end. Both kinds of time locate in present, not in past or future. Past exists in present only as memory. and future only as anticipation. Therefore legal practices need not commit to the reality of past and future. This 'legal presentism' is well philosophically explained by 'evidence presentism'. Presentism is ontology of time which insists that the only present things are real, and that past and future are unreal. What makes propositions about past or future true is a difficult problem for presentists. In this essay. I support 'evidence presentism' proposed by Tora Koyama. that insists only present evidences can be truthmakers. This theory is compatible with legal practices. Only the present things, including conventions naturalistically described, can generate an agency with accountability and time structure of legal practices, not vice versa.

7 0 0 0 OA シンポジウム概要—市ヶ谷死闘編—

- 著者

- 住吉 雅美

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2003, pp.121-132, 2004-10-20 (Released:2008-11-17)

6 0 0 0 OA 制度のなかで生きるとはどのような経験か—公共的正当化論の再考に向けて—

- 著者

- 那須 耕介

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2000, pp.164-172, 2001-10-30 (Released:2008-11-17)

- 参考文献数

- 9

6 0 0 0 OA 法における擬制

- 著者

- 小西 美典

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1961, pp.161-178, 1962-04-30 (Released:2009-02-12)

- 参考文献数

- 20

6 0 0 0 OA 統一テーマ「ジェンダー、セクシュアリテイと法」について

- 著者

- 住吉 雅美

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2003, pp.1-6,236, 2004-10-20 (Released:2008-11-17)

The Annual Meeting of Legal Philosophy 2003 under the title of “GENDER, SEXUALITY AND THE LAW” was held under the auspices of The Japan Association of Legal Philosophy (JALP), in Tokyo, on November, 21-22, 2003. Issues of this meeting were as follows: 1. From a standpoint of feminism, scholars try to criticize and reexamine the main subjects of legal philosophy (especially justice and rights), and the basic structure and fundamentals of orthodox legal theory. Furthermore, we try to find gender-bias in theories, and to restructure the political and social system. 2. Legal philosphers do not only reply to feminists' criticism of theories of justice, rights and liberalism, but also present their generous intellect which is tolerant of criticism. 3. Scholars both examine anti-feminist critiques that have occured from the margins of the feminism-debate, inspired by postmodern philosophies, and investigate the movements of feminism's self-innovation. We also try to criticize the dualism of gender and hegemonic heterosexuality, and to deconstruct identities (including the definition of ‘woman’) that are oppressive. We hope that this will lead to the recognition of diversified sexualities.

6 0 0 0 OA 憲法学からみた家族の「公」と「私」-吉田克己報告へのコメント

- 著者

- 高井 裕之

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2000, pp.62-66, 2001-10-30 (Released:2008-11-17)

- 参考文献数

- 13

6 0 0 0 OA ジョン・ロックと近代政治原理

6 0 0 0 OA ケアの倫理と制度—三人のフェミニストを真剣に受けとめること—

- 著者

- 川本 隆史

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2003, pp.19-31,235, 2004-10-20 (Released:2008-11-17)

- 参考文献数

- 15

Feminists have presented perceptive criticisms of the currently dominant theories and practices of the moral and social orders, and some of them have made efforts to replace these theories and practices with the ‘ethic of care’ and its application to distinctively institutional domains. In this paper I first look at a few of the most important attempts made in this direction; then I offer suggestions to further promote this movement. We owe the feminist insight of the ethic of care, as opposed to the male-centered ‘ethic of justice’, to Carol Gilligan's epoch-making In a Different Voice. In Starting at Home Nel Nodding develops the ethic of care in a couple of respects. First, she shows that what matters is not just a person caring for another but rather reciprocity between the one-caring and the cared-for. Second, she applies the ethic of care to the context of social policy and develops the conception of a ‘caring society’. Mari Osawa can be said to virtually join these ethicists of care when she proposes governmental policies intended to create in the Japanese society the conditions in which men and women can participate together in politics, at the workplace and at home, and lead exciting and fulfilling lives. I make three recommendations to advance the movement represented by these three authors. First, we should be even more aware that what may look like trifling matters in everyday life do have political significance. Second, we should take a step to implement the ethic of care in the contexts of education, broadly construed. And thirdly, we should respect people's right to define themselves; and hence we (women and men alike) should be careful as to how to address those exposed to systematic unfair treatment in the society, specifically, female persons.

6 0 0 0 OA 妥当な法律と順法の問題 アメリカ法哲学の一断面

- 著者

- 矢崎 光圀

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1965, pp.81-109, 1966-04-20 (Released:2009-02-12)

- 参考文献数

- 35

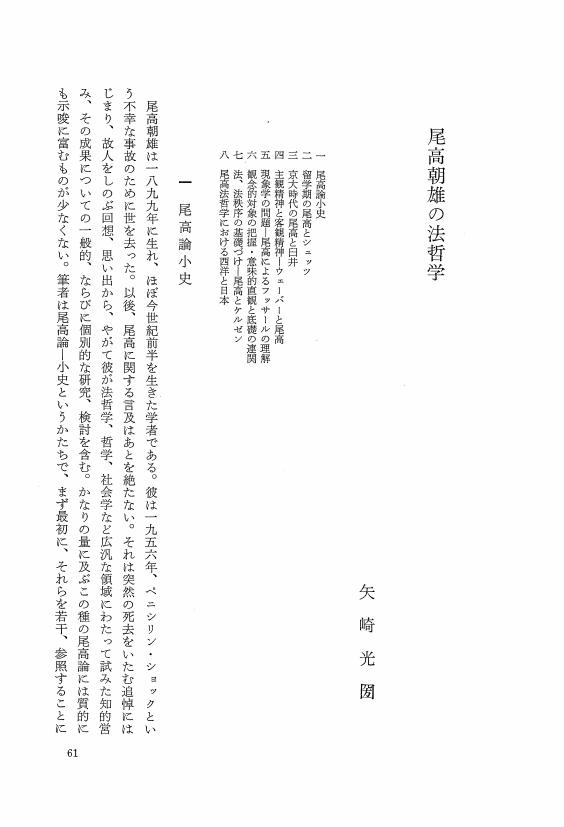

5 0 0 0 OA 尾高朝雄の法哲学

- 著者

- 矢崎 光圀

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1979, pp.61-86, 1980-10-30 (Released:2008-11-17)

- 参考文献数

- 29

5 0 0 0 OA 日本憲法学における「科学」と「思想」

- 著者

- 樋口 陽一

- 出版者

- 日本法哲学会

- 雑誌

- 法哲学年報 (ISSN:03872890)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1981, pp.1-16, 1982-10-30 (Released:2008-11-17)

- 参考文献数

- 4