10 0 0 0 OA 甲州式目(松平文庫本)校訂原文・注釈・現代語訳

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 立正大学大学院文学研究科

- 雑誌

- 大学院紀要 = Bulletin of the Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology Rissho University (ISSN:09112960)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.34, pp.1-30, 2018-03-31

9 0 0 0 OA 鉛同位体比法を用いた東アジア世界における金属の流通に関する歴史的研究

- 著者

- 平尾 良光 飯沼 賢司 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 別府大学

- 雑誌

- 新学術領域研究(研究課題提案型)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 2009

10~17世紀における日本の銅や鉛の生産と流通に関して、経筒、梵鐘、鉄砲玉やキリスト教関連遣物などの実資料に関する鉛同位体比から、それら資料の産地を推定し、銅や鉛の流通の実態を明らかにした。特に16世紀後半以降においては火縄銃の弾や銀生産のために、戦国大名にとって鉛は必須の材料であった。鉛の急激な利用増のため、外国産鉛の流入が日本の歴史に大きな影響を与えたことが明らかになった。

8 0 0 0 明代「冊封」の古文書学的検討:日中関係史の画期はいつか

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.127, no.2, pp.1-41, 2018

室町幕府の首長が明皇帝によって日本国王に封じられるという、日中関係史における画期について、1402(建文4)年でなく1404(永楽2)年が正しいとする学説が有力になっている。しかしそれらは厳密な史料の読みに裏づけられた学説とはいいがたい。<br>根拠とする史料が原態からどれくらい隔たっているかを正確に測定しながら、一歩一歩史実を確定していくという、古文書学的な手法を用いて検証してみると、1404年説を採った場合に受封者と認定しうるのは、足利義満・豊臣秀吉の二人しか残らない。室町幕府の首長が東アジアの国際社会で日本国王として承認されるという、「封」の実質を重視する観点からは、1402年のほうがはるかに重要な画期である。皇帝が「封」の実質を実現するために発給する文書には、誥命・詔書・勅諭など、対象者のランクに応じて多様な様式が使い分けられていた。<br>琉球の中山・山南・山北の三王に目を転じると、三山相互、あるいは明との関係の推移にともなって、皇帝が王を「封」ずる文書のほか、暦・印・冠服などがさまざまなタイミングと順番と目的に従って与えられていく状況が観察できる。「封」をめぐる多様な皇帝文書の使い分けは琉球の場合にも認められ、しかも比較的短い間に移り変わっていた。<br>さらに対象を「東南夷」(東アジア~インド沿海部の諸国)に拡げて見ていくと、洪武・建文年間には「封」が最高ランクの文書「誥命」でおこなわれたのは高麗・朝鮮のみだったが、永楽年間には一変して、印とのセットで遠距離の諸国に気前よく与えられるようになる。その背景には、鄭和の大遠征に象徴されるような、天下に威と徳を及ぼそうとする永楽帝の対外姿勢があった。<br>最後に、琉球をふくむ日本列島地域に伝えられた史料、すなわち何通かの外交文書の原本や『歴代宝案』『善隣国宝記』という外交文書集には、明代の国際秩序の解明にとって他に換えがたい価値があることを指摘した。

6 0 0 0 OA 鉄砲伝来と倭寇勢力 : 宇田川武久氏との討論

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 国立歴史民俗博物館

- 雑誌

- 国立歴史民俗博物館研究報告 = Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History (ISSN:02867400)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.201, pp.81-96, 2016-03-30

本誌第一九〇集に掲載された宇田川武久氏の論文「ふたたび鉄炮伝来論―村井章介氏の批判に応える―」に対する反論を目的に、「鉄砲は倭寇が西日本各地に分散波状的に伝えた」とする宇田川説の論拠を史料に即して検証して、つぎの三点を確認した。①「村井が鉄砲伝来をヨーロッパ世界との直接のであいだと述べている」と反復する宇田川氏の言明は事実誤認である。②〈一五四二年(または四三年)・種子島〉を唯一の鉄砲伝来シーンと考える必要はなく、倭寇がそれ以外のシーンでも鉄砲伝来に関わった可能性はあるが、宇田川氏はそのオールタナティブを実証的に示していない。③一五四〇~五〇年代の朝鮮・明史料に見える「火砲(炮)」の語を鉄砲と解する宇田川説は誤りであり、それゆえこれらを根拠に鉄砲伝来を論ずることはできない。以上をふまえて、一六世紀なかば以降倭寇勢力が保有していた鉄砲と、一六世紀末の東アジア世界戦争(壬辰倭乱)において日本軍が駆使した鉄砲ないし鉄砲戦術との関係を、どのように捉えるべきかを考察した。壬辰倭乱直前まで、朝鮮は倭寇勢力が保有する鉄砲を見かけていたかもしれないが、軍事的脅威と感じられるほどのインパクトはなかったので、それに焦点をあわせた用語も生まれなかった。朝鮮が危惧していたのは、中国起源の従来型火器である火砲が、明や朝鮮の国家による占有を破って、倭寇勢力や日本へ流出することであった。しかしその間、戦国動乱さなかの日本列島に伝来した新兵器鉄砲が、軍事に特化した社会のなかで、技術改良が重ねられ、また組織的利用法が鍛えあげられ、やがて壬辰倭乱において明や朝鮮にとって恐るべき軍事的脅威となった。両国は鉄砲を「鳥銃」と呼び、鹵獲した鳥銃や日本軍の捕虜から、鉄砲を駆使した軍事技術をけんめいに摂取しようとした。

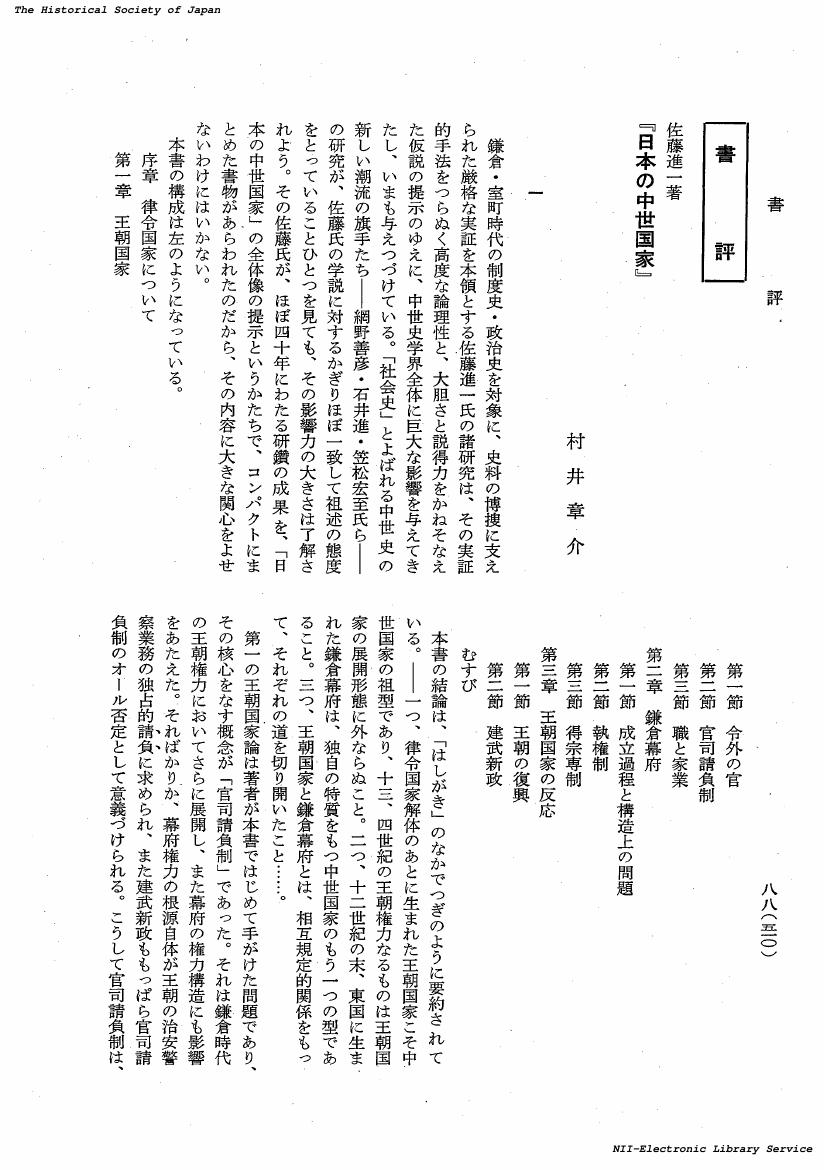

6 0 0 0 OA 佐藤進一著『日本の中世国家』

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.93, no.4, pp.510-521, 1984-04-20 (Released:2017-11-29)

3 0 0 0 蒙古襲来と鎮西探題の成立

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.87, no.4, pp.411-453,552-55, 1978

The machinery which the Kamakura Bakufu set up in Kyushu to govern a large area has been much studied from the point of view of institutional history, with priority given to its judicial aspect. In the present article, attention is given to two aspects which have been largely overlooked, namely, its close relationship with the office of county shugo 守護 (Protector) in Kyushu, and its connection with the "tokusei" (徳政 : political innovation), especially the protection of the estates of Shinto shrines. As to the first point, at least eleven counties saw their shugo replaced at the same time towards the end of 1275. This reshuffle formed part of the plan for a counter-attack on Ko-ryo, which had been used by the Yuan as a base for their invasion of Japan. In the reshuffle, the arrival in Kyushu of Kanesawa Sanemasa 金沢実政 as deputy for the shugo of the county of Buzen 豊前 was the starting-point of the political process leading to the establishment of the office of Chinzei-tandai 鎮西探題. There followed the arrival of Hojo Tokisada 北条時貞 as shugo of Hizen 肥前 in 1281 and the exercise of military power over the whole of Kyushu by Hojo Kanetoki 北条兼時, who was appointed shugo of Higo 肥後 in 1293. These appointments were made directly in response to the external tension caused by the Mongol invasion, and resulted in the extension of the influence of the Hojo clan. This process reached its peak when in a short space of time the offices of shugo of four counties, Hizen, Higo, Buzen and Osumi 大隅, were monopolized by Kanesawa Sanemasa, who returned to Kyushu as Chinzei-tandai in 1296, and his close relatives. The development of regional power, pointing to the future territorial government system under the shugo, had already begun. As for the second point, the Tokuso (得宗 : head of the Hojo clan) government, which dominated the Kamakura Bakufu, framed a series of policies called Koan-tokusei 弘安徳政 in 1284 after the Mongol invasion. These policies were an attempt to elevate the Bakufu into a central power ruling over the whole of Japan by having the Bakufu decide cases concerning the land-tenure problems of shrine estates and by organizing the people under the control of manor lords into a new feudal hierarchy. The policies were, however, upset by a coup-d'etat in November 1285 in which the leader of the innovatory movement, Adachi Yasumori 安達泰盛, was killed. What the post-coup Tokuso government inherited from the Koan-tokusei and developed still further was a policy of almost blind protection of the Shinto shrines. Although the Tokuso government was prematurely possessed of several characteristics of the Muromachi Bakufu, it did not attempt to reform the shogun-gokenin (将軍-御家人 : lord-vassal) relationship which was the institutional backbone of the Kamakura Bakufu. Lacking any legitimate claim to exercise domination over the gokenin, it sought to enhance its power by obtaining a huge material base. But this was only to estrange the vassals and to intensify the isolation of the government. The Tokuso government even feared that the Kanesawa family, which belonged to the Hojo clan, might extend its influence in Kyushu, and a step was taken to check the process by which the Kanesawa were becoming a territorial power. In this way, the government could not avoid continually giving rise to its own critics and opponents, and so it deepened its reliance on divine protection in order to escape from the sense of isolation.

3 0 0 0 OA 朝鮮史料から見た「倭城」

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 東洋史研究会

- 雑誌

- 東洋史研究 (ISSN:03869059)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.66, no.2, pp.229-266, 2007-09

2 0 0 0 『看聞日記』の引用表現について

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 日本古文書学会 ; 1968-

- 雑誌

- 古文書研究 = The Japanese journal of diplomatics (ISSN:03862429)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.92, pp.76-89, 2021-12

2 0 0 0 OA 蒙古襲来と鎮西探題の成立

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.87, no.4, pp.411-453,552-55, 1978-04-20 (Released:2017-10-05)

The machinery which the Kamakura Bakufu set up in Kyushu to govern a large area has been much studied from the point of view of institutional history, with priority given to its judicial aspect. In the present article, attention is given to two aspects which have been largely overlooked, namely, its close relationship with the office of county shugo 守護 (Protector) in Kyushu, and its connection with the "tokusei" (徳政 : political innovation), especially the protection of the estates of Shinto shrines. As to the first point, at least eleven counties saw their shugo replaced at the same time towards the end of 1275. This reshuffle formed part of the plan for a counter-attack on Ko-ryo, which had been used by the Yuan as a base for their invasion of Japan. In the reshuffle, the arrival in Kyushu of Kanesawa Sanemasa 金沢実政 as deputy for the shugo of the county of Buzen 豊前 was the starting-point of the political process leading to the establishment of the office of Chinzei-tandai 鎮西探題. There followed the arrival of Hojo Tokisada 北条時貞 as shugo of Hizen 肥前 in 1281 and the exercise of military power over the whole of Kyushu by Hojo Kanetoki 北条兼時, who was appointed shugo of Higo 肥後 in 1293. These appointments were made directly in response to the external tension caused by the Mongol invasion, and resulted in the extension of the influence of the Hojo clan. This process reached its peak when in a short space of time the offices of shugo of four counties, Hizen, Higo, Buzen and Osumi 大隅, were monopolized by Kanesawa Sanemasa, who returned to Kyushu as Chinzei-tandai in 1296, and his close relatives. The development of regional power, pointing to the future territorial government system under the shugo, had already begun. As for the second point, the Tokuso (得宗 : head of the Hojo clan) government, which dominated the Kamakura Bakufu, framed a series of policies called Koan-tokusei 弘安徳政 in 1284 after the Mongol invasion. These policies were an attempt to elevate the Bakufu into a central power ruling over the whole of Japan by having the Bakufu decide cases concerning the land-tenure problems of shrine estates and by organizing the people under the control of manor lords into a new feudal hierarchy. The policies were, however, upset by a coup-d'etat in November 1285 in which the leader of the innovatory movement, Adachi Yasumori 安達泰盛, was killed. What the post-coup Tokuso government inherited from the Koan-tokusei and developed still further was a policy of almost blind protection of the Shinto shrines. Although the Tokuso government was prematurely possessed of several characteristics of the Muromachi Bakufu, it did not attempt to reform the shogun-gokenin (将軍-御家人 : lord-vassal) relationship which was the institutional backbone of the Kamakura Bakufu. Lacking any legitimate claim to exercise domination over the gokenin, it sought to enhance its power by obtaining a huge material base. But this was only to estrange the vassals and to intensify the isolation of the government. The Tokuso government even feared that the Kanesawa family, which belonged to the Hojo clan, might extend its influence in Kyushu, and a step was taken to check the process by which the Kanesawa were becoming a territorial power. In this way, the government could not avoid continually giving rise to its own critics and opponents, and so it deepened its reliance on divine protection in order to escape from the sense of isolation.

2 0 0 0 OA 日本史と世界史のはざま

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 日本学術協力財団

- 雑誌

- 学術の動向 (ISSN:13423363)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.16, no.10, pp.10_37-10_39, 2011-10-01 (Released:2012-02-15)

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 朝鮮史研究会 ; 1965-

- 雑誌

- 朝鮮史研究会論文集 (ISSN:05908302)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.58, pp.5-29, 2020-10

1 0 0 0 佐藤進一著『日本の中世国家』

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.93, no.4, pp.510-521, 1984

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.97, no.11, pp.1900-1901, 1988-11-20 (Released:2017-11-29)

1 0 0 0 吉田定房奏状はいつ書かれたか

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 吉川弘文館

- 雑誌

- 日本歴史 (ISSN:03869164)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.587, pp.92-96, 1997-04

1 0 0 0 『看聞日記』の舞楽記事を読む

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 立正大学文学部

- 雑誌

- 立正大学文学部論叢 (ISSN:0485215X)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.138, pp.37-55, 2015-03

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.98, no.7, pp.1271-1272, 1989-07-20 (Released:2017-11-29)

1 0 0 0 OA 明代「冊封」の古文書学的検討

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.127, no.2, pp.1-41, 2018 (Released:2019-02-20)

室町幕府の首長が明皇帝によって日本国王に封じられるという、日中関係史における画期について、1402(建文4)年でなく1404(永楽2)年が正しいとする学説が有力になっている。しかしそれらは厳密な史料の読みに裏づけられた学説とはいいがたい。 根拠とする史料が原態からどれくらい隔たっているかを正確に測定しながら、一歩一歩史実を確定していくという、古文書学的な手法を用いて検証してみると、1404年説を採った場合に受封者と認定しうるのは、足利義満・豊臣秀吉の二人しか残らない。室町幕府の首長が東アジアの国際社会で日本国王として承認されるという、「封」の実質を重視する観点からは、1402年のほうがはるかに重要な画期である。皇帝が「封」の実質を実現するために発給する文書には、誥命・詔書・勅諭など、対象者のランクに応じて多様な様式が使い分けられていた。 琉球の中山・山南・山北の三王に目を転じると、三山相互、あるいは明との関係の推移にともなって、皇帝が王を「封」ずる文書のほか、暦・印・冠服などがさまざまなタイミングと順番と目的に従って与えられていく状況が観察できる。「封」をめぐる多様な皇帝文書の使い分けは琉球の場合にも認められ、しかも比較的短い間に移り変わっていた。 さらに対象を「東南夷」(東アジア~インド沿海部の諸国)に拡げて見ていくと、洪武・建文年間には「封」が最高ランクの文書「誥命」でおこなわれたのは高麗・朝鮮のみだったが、永楽年間には一変して、印とのセットで遠距離の諸国に気前よく与えられるようになる。その背景には、鄭和の大遠征に象徴されるような、天下に威と徳を及ぼそうとする永楽帝の対外姿勢があった。 最後に、琉球をふくむ日本列島地域に伝えられた史料、すなわち何通かの外交文書の原本や『歴代宝案』『善隣国宝記』という外交文書集には、明代の国際秩序の解明にとって他に換えがたい価値があることを指摘した。

1 0 0 0 IR 鉄砲伝来と倭寇勢力 : 宇田川武久氏との討論

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 国立歴史民俗博物館

- 雑誌

- 国立歴史民俗博物館研究報告 = Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History (ISSN:02867400)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.201, pp.81-96, 2016-03

本誌第一九〇集に掲載された宇田川武久氏の論文「ふたたび鉄炮伝来論―村井章介氏の批判に応える―」に対する反論を目的に、「鉄砲は倭寇が西日本各地に分散波状的に伝えた」とする宇田川説の論拠を史料に即して検証して、つぎの三点を確認した。①「村井が鉄砲伝来をヨーロッパ世界との直接のであいだと述べている」と反復する宇田川氏の言明は事実誤認である。②〈一五四二年(または四三年)・種子島〉を唯一の鉄砲伝来シーンと考える必要はなく、倭寇がそれ以外のシーンでも鉄砲伝来に関わった可能性はあるが、宇田川氏はそのオールタナティブを実証的に示していない。③一五四〇~五〇年代の朝鮮・明史料に見える「火砲(炮)」の語を鉄砲と解する宇田川説は誤りであり、それゆえこれらを根拠に鉄砲伝来を論ずることはできない。以上をふまえて、一六世紀なかば以降倭寇勢力が保有していた鉄砲と、一六世紀末の東アジア世界戦争(壬辰倭乱)において日本軍が駆使した鉄砲ないし鉄砲戦術との関係を、どのように捉えるべきかを考察した。壬辰倭乱直前まで、朝鮮は倭寇勢力が保有する鉄砲を見かけていたかもしれないが、軍事的脅威と感じられるほどのインパクトはなかったので、それに焦点をあわせた用語も生まれなかった。朝鮮が危惧していたのは、中国起源の従来型火器である火砲が、明や朝鮮の国家による占有を破って、倭寇勢力や日本へ流出することであった。しかしその間、戦国動乱さなかの日本列島に伝来した新兵器鉄砲が、軍事に特化した社会のなかで、技術改良が重ねられ、また組織的利用法が鍛えあげられ、やがて壬辰倭乱において明や朝鮮にとって恐るべき軍事的脅威となった。両国は鉄砲を「鳥銃」と呼び、鹵獲した鳥銃や日本軍の捕虜から、鉄砲を駆使した軍事技術をけんめいに摂取しようとした。The purpose of my present article is to reply to the article of Udagawa Takehisa that appeared in issue 190 of this journal with the title "Another Study of the Introduction of Guns to Japan: As a Counter-argument to the Criticism of Dr. Shōsuke Murai". In my article I examined Udagawa's theory that says, "wakō-pirates introduced and gradually distributed muskets to several places in Western Japan". During my examination of his arguments based on the historical sources I came to the following three conclusions.First, the often repeated statement of the author that says, "Murai states that the introduction of muskets was a direct encounter with the European world", is a misunderstanding of that what I stated in fact in my article. Second, I agree with the author that it is not necessary to think about the year 1542 (or 1543) and the island Tanegashima as the only possible time and place for the introduction of muskets, and that it is possible that wakō-pirates also played a part in the introduction of muskets in other different ways. Still, the problem is that the author does not provide concrete examples or evidences for possible alternatives based on the historical sources that would support this argument. Third, the author's theory, according to which he is interpreting "huopao / hwap'o 火砲(炮) (cannon)" - a word that can be seen in the Chinese and Korean sources in the 1540-50s- as "musket", is a mistake. Therefore, it is not possible to discuss the introduction of musket based on this theory.Based on these conclusions, I examined the following question: What was the relationship between those muskets possessed by wakō-pirates after the middle of the 16th century and the muskets used by the Japanese army during the war in the East Asian world at the end of the 16th century (the so called Imjin war)?It is possible that Koreans saw the muskets of wakō-pirates before the Imjin war, but these muskets had probably no impact on them, and the Koreans did not feel yet the threat of muskets at that time. Therefore they did not create a special word for musket. Rather, Koreans felt apprehension that "huopao / hwap'o (cannon)", the conventional firearms of Chinese origin would flow out from Korea or China into the hand of wakō-pirates or Japanese.But during the following years, musket, the new weapon introduced to Japan in the midst of the disturbances of the Warring States period, underwent several technical improvements in the Japanese society that was characterized by continuous wars. Further, with the time Japanese soldiers became also perfectly trained in the use of musket in organized groups. Thus, musket soon became a fearful military menace to Ming China and Chosŏn Korea during the Imjin war. Both countries called musket "niaochong / choch'ong 鳥銃 (fowling piece)" and both of them eagerly tried to learn the military technique of muskets from captured Japanese soldiers and the confiscated "fowling pieces".

1 0 0 0 一五世紀初頭、日明間の使節往来 : 足利義満論の一環として

- 著者

- 村井 章介

- 出版者

- 七隈史学会

- 雑誌

- 七隈史学 (ISSN:13481304)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.18, pp.1-15,図巻頭1枚, 2016-03