1 0 0 0 OA 藤川信夫著『教育学における神話学的方法の研究』

- 著者

- 今井 重孝

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.79, pp.132-136, 1999-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

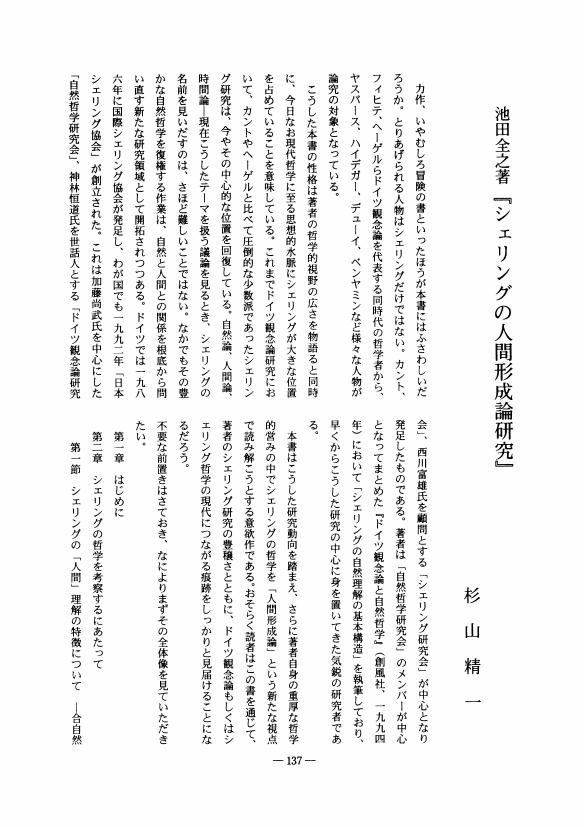

1 0 0 0 OA 池田全之著『シェリングの人間形成論研究』

- 著者

- 杉山 精一

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.79, pp.137-142, 1999-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 山崎洋子著『ニイル「新教育」思想の研究-社会批判にもとづく「自由学校」の地平-』

- 著者

- 宮寺 晃夫

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.79, pp.143-148, 1999-05-10 (Released:2010-01-22)

1 0 0 0 OA 杉浦宏編『日本の戦後教育とデユーイ』

- 著者

- 米澤 正雄

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.79, pp.149-150, 1999-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 研究討議に関する総括的報告

- 著者

- 毛利 陽太郎 林 忠幸

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.79, pp.18-21, 1999-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 学校は、今何が出来るか 公共性の構築へ向けて

- 著者

- 小玉 重夫

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.79, pp.22-27, 1999-05-10 (Released:2010-05-07)

- 参考文献数

- 15

1 0 0 0 OA 「学校は何のために」と問うことの意味 教育臨床学の視点から

- 著者

- 諸富 祥彦

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.79, pp.27-32, 1999-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 学校のために、今何が出来るか

- 著者

- 毛利 猛

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.79, pp.32-38, 1999-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 課題研究についての総括的報告

- 著者

- 宇佐美 寛

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.79, pp.39-43, 1999-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 伊藤仁斎における教育思想の構造について 「孔孟の意味血脈」を視座とする教育思想の特質

- 著者

- 山本 正身

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.79, pp.44-58, 1999-05-10 (Released:2010-05-07)

- 参考文献数

- 24

Ito Jinsai's educational thought consisted mainly of the relationships among three conceptions; namely, human nature, the Way (of Man), and the teachings (of both Confucius and Mencius). These conceptions in turn were known to him through his inquiry into the essence of the thoughts of Confucius and of Mencius.For Jinsai the Way (of Man) should be found in daily human relations, and it was first generalized and presented to people as teachings by Confucius. However, as people were separated from Confucius's times, they interpreted the Way (of Man) arbitrarily; otherwise, they despaired of their ability to practice morality. To overcome these difficulties, Mencius contended that the Way (of Man) meant humanity and justice in human relations, and that man's inborn nature wa good.Thus Jinsai's educational thought was focused on a problem : how to urge people to participate in daily human relations. It would be said that his thought was one of the prominent achievements in educational thought which was constructed on the basis of Confucianism.

- 著者

- 小林 万里子

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.79, pp.59-74, 1999-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

- 参考文献数

- 41

Am Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts, als in Hamburg ein staatliches Volksschulwesen eingerichtet wurde, hatten die Volksschullehrer über ihre Arbeit, also Erziehung und Schulverwaltung wenige Rechte zu sagen. Sie kritisierten die Verbürokratisierung der Schule. Um ihre Rechte von der Offentlichkeit anerkannt zu sehen, starteten sie nicht nur eine reformpädagogische Bewegung (Kunsterziehungsbewegung oder Arbeitsschulbewegung), sondern auch eine soziale Bewegung, oder nahmen daran teil. In der Bewegung entwarfen sie die 'neue Schule' als Alternative zur 'alten Schule'. Um diesen Entwurf zu realisieren, verlangten sie öffentlich eingerichtete Versuchsschulen.In der Versuchsschule Berliner Tor, die 1919 entstand, wurde eine Erziehung eingeführt, die auf dem Interesse und der Förderung des Kindes basiert, wobei diese von seiten der Lehrer angefaßt wurden. Die Lehrer der Berliner Tor Schule forderten nicht nur das Recht des Kindes, sondern auch immer dasjenige der Lehrer selbst.Daher stellte sich heraus, daß die Pädagogik 'vom Kinde aus' in der Hamburger Schulreformbewegung aufgrund der Forderung der Lehrer selbst nach Selbständigkeit entworfen wurde.

1 0 0 0 OA 想起としての探究と学習 『メノン』における想起説の再検討

- 著者

- 片山 勝茂

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.79, pp.75-92, 1999-05-10 (Released:2010-05-07)

- 参考文献数

- 82

The theory of recollection in the Meno (TRM) has been generally interpreted as the theory 'that learning is recollection of knowledge acquired before birth' (Bluck). Recently Moravcsik and other scholars have argued that only 'learning taking the form of inquiry is recollection'. However, knowing consists of two distinct parts : inquiring and finding out, teaching and learning. 'Plato identifies knowledge with recollection' (Irwin).According to Guthrie, in TRM a distinction is made 'for the first time between empirical and a priori knowledge'. Only the latter (e.g.geometry) is the object of recollection, and genuine knowledge. However, this established view does not correspond with the text (81c5-9, 85c6-7, 97a-c). 'Someone who knows the road to Larisa' (97a9) has empirical knowledge. This is not an analogy, but a concrete example of knowledge (pace Bluck). Recollection covers all knowledge including skills and virtues.At 97-98, Plato distinguishes for the first time between true belief and knowledge. Only the latter is tied down by the considerration of reason (αιτιαζ λογισμοζ), and this is called 'recollection'. This shows Plato's exellent insight. A lot of scholars are 'wrong to restrict aitias logismos, and recollection as a whole, to reasoning relying on logical necessity' (Irwin).Plato insists that (a) all the slave-boy's answers were his own belief, and that (b) these beliefs were originally inside him. The point (a) is just, but does not guarantee (b). The point (b) is a fallacy. This has been the problem with TRM.The insights in Plato's TRM can contribute to modern pedagogy which is urged to reexamine learning itself.

1 0 0 0 OA H・-E・テノルト著小笠原道雄・坂越正樹監訳『教育学における「近代」問題』

- 著者

- 原 聡介

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1998, no.78, pp.80, 1998-11-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA W・H・プレーガー著 増渕幸男監訳『シュライアーマッハーの哲学』

- 著者

- 越後 哲治

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1998, no.78, pp.81, 1998-11-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 天野正治 結城忠 別府昭郎編著『ドイツの教育』

- 著者

- 今井 重孝

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1998, no.78, pp.82, 1998-11-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 戦後教員養成理念の推移をめぐる問題点と課題

- 著者

- 市村 尚久

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.79, pp.1-5, 1999-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA これからの学校の役割と教員養成の理念

- 著者

- 高橋 勝

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.79, pp.5-11, 1999-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

- 参考文献数

- 15

1 0 0 0 OA 「教員」は「養成」できるのか 教員養成教育における対立構図の克服へ向けて

- 著者

- 松浦 良充

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1999, no.79, pp.12-17, 1999-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

- 参考文献数

- 14

1 0 0 0 OA 『ツァラトゥストラ』にみるニーチェの自己形成思想

- 著者

- 相澤 伸幸

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1998, no.78, pp.1-16, 1998-11-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

- 参考文献数

- 45

Nietzsche gehort zu den bedeutendsten Denker der Gegenwant, was heutzutage jedermann anerkennt. Aber Ernst Weber hat es als erster angefangen, in den ordentlichen Forschungen Nietzsche als Erzieher oder Pädagogen zu behandeln. Seitdem haben viele Forsche ihn immer für Erzieher oder Pädagogen gehalten. So ist such die Absicht der vorliegenden Abhandlung, vorwiegend “Nietzsche als Erzieher oder Pädagogen” in Also sprach Zarathustra (1883-85) zu präzisieren.In Zarathustra, besonders in Von den drei Verwandlungen des Geistes-Kamel, Löwe, Kindschildert Nietzsche ausführlich, wie man sich bildet, und legt seine Gedanken über Selbstbildung vor. Vom pädagogischen Standpunkt aus, das heißt von dem des Selbst-bildung (werdung) -prozesses aus, bedeutet das Kind in Zarathustra die Flexibilität und die Vielfalt der Bildungsmoglichkeiten. Das ist bei dem Übermensch auch der Fall. Der Übermensch ist der wichigste Begriff für die Selbstbildungslehre des Menschen, aber Nietzsche beschreibt nicht Kind und Übermensch als Substanz, sondern als etwas Unbedingtes, Unzeitliches und Unzweckmäßiges. Dieser Auslegung, die großes Gewicht auf Bildung legt, ist noch etwas näher nachzugehen, und zwar im ganzen Denken Nietzsches.Nach Nietzsche wird man nicht dadurch, daß man sich nach und nach ausbildet, zum Kind oder Übermensch, folglich soll man sich nitch ein beständiges Wachstum zur Vervollkommnung vorstellen. Sondern alles bildet sich zugleich, und übereinander und durcheinander und gegeneinander, was Nietzsche mit der Formel 'der große Mittag' bezeichnet, wo Kind und Übermensch sich mit der ewigen Wiederkunft des Gleichen verbinden. Dies ist der Gesichtspunkt, den wir in Nietzsches Selbstbildungslehre auf ihrem wesenhaftsten Punkte finden. Am Ende wird noch auf einige Schwierigkeiten von Nietzschestudien hingewiesen.

1 0 0 0 OA 近代的教養としての修辞学 フイエの「観念力」に関する一考察

- 著者

- 斎藤 桜子

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1998, no.78, pp.17-33, 1998-11-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

- 参考文献数

- 62

Cet article examine la philosophie des idées-forces de Fouillée dans le cadre de l'histoire de l'enseignement secondaire en France. A la fin du X IXe siècle, cet enseignement subit des changements fondamentaux. Ce qui est remarquable, c'est le déclin de la rhétorique traditionelle au fur et à mesure de l'essor de la culture scientifique. Dans ce contexte Fouillée essaye de construire un enseignement de la rhétorique fondé sur la philpsophie des idées-forces.Dans les courants philosophiques de l'epoque, sa théorie des idées-forces se situe entre deux extrêmes : le positivisme et l'idéalism. Chez Fouillée, it s'agait d'une idée agissante, motrice et directrice tendant vers la réalisation d'un idéal. Selon lui, l'idée-force se caractérise par le processus appétitif : sensation, émotion, et appétition.Pour ce qui est de l'enseignement classique, formulant des objections à la culture scientifique, Fouillée présente le latin comme une langue vivante. Parce qu'il y a des mots-forces qui sont les substituts et les symboles des idées-forces. C'est-à-dire que le mot et l'idée sont des verbes. Et en particulier, l'éloquence et la poésie des anciens parlent à l'imagination et aux sentiments naturels. Les classiques permettent de produire des élites qui sont capables de persuader.On peut dire ainsi que Fouillée accorde une grande importance à la rhétorique pour contester la spécialisation de la culture moderne et pour harmoniser cette dernière avec l'héritage antique.