1 0 0 0 OA 日本の道徳教育 (後篇) その世界観的基磯、とくに政教分離の問題

- 著者

- 稲富 栄次郎

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1965, no.11, pp.1-19, 1965-05-25 (Released:2009-09-04)

- 参考文献数

- 8

In the first half of my treatise I have tried to clarify the indispensable role religion plays in the formation of man's moral character, and the consequent necessity of religious principles in moral education. I have at the same time described the present condition of religious education in Europe. However, it is also a fact that, concerning the relationship between religion and politics, there have been movements, through history, to secularize education in various parts of the world.In this half of my treatise I have attempted to explain the separation of Church and State which took place in France and in the United States. The moral education of France exercised a great influence on that of Japan since the early years of Meiji, while that of the United States become influential after the Second World War. However, whether the moral education carried on in France or the courses in ethics and religion given in the United States are adaptable without any change to Japan is a question still to be answered. Before attempting to solve this problem a thorough study should be made of the history of the separation movement in Japan, which developed in a fashion quite different from similar movements in France and the United States.

1 0 0 0 OA ウィルマンの教育思想の研究 永遠教育学の視点を中心として

- 著者

- 溝上 茂夫

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1965, no.11, pp.20-35, 1965-05-25 (Released:2009-09-04)

- 参考文献数

- 3

The period in which Willmann was active as a philosopher and educator was still under the deep influence of the Enlightenment. Education was no exception.The exponents of the Enlightenment disdained the Middle Ages, looked on the thoughts of the time as 'ancilla theologiae', and proclaimed themselves as the givers of illuminating new light. Cutting, thus, the historical continuity, they abandoned the precious moral and spiritual heritage of the past. They made man and his subjective reasoning the highest norm of all judgments. In promising man's intellectual liberation and development, they fell into a quagmire of self-delusion, opening the way to individualism, subjectivism, naturalism, relativism, secularism and materialism, etc.Otto Willmann devoted his whole life as philosopher and educator to fight against the world-view of the Enlightenment, i.e. present Nominalism and its influence on educational ideologies. Starting from the individualistic education of Herbert and tracing backwards up the stream of history, Willmann reached on the opposite side of the Enlightenment, namely the heights of the Greco-Christian idealistic world-view and educational Ethos. The Greco-Christian Idealism is not like German subjectivistic idealism seen in Kant, Fichte, Schilling and Hegel. This Idealism is the Idealism of Logos founded and developed by Plato, Aristoteles, St. Augustinus and St. Thomas Aquinus. The Greco-Christian Idealism according to Willmann possess the eternal creative life and substance (teaching of everlasting values (μεγιστον μαθημα, unum necessarium)) and leads man toward eternal God. Therefore, it is 'philosophia perennis' and 'paedagogia perennis'.

1 0 0 0 OA スペンサーにおける社会と教育 社会有機体説を中心として

- 著者

- 赤塚 徳郎

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1965, no.11, pp.36-55, 1965-05-25 (Released:2009-09-04)

- 参考文献数

- 42

It was during the Victorian Era that Spencer brought forth his theory of social organism, based on the equality and the freedom of man. An individual has the liberty to pursue happiness and to use his faculties for that end. Such individuals, during the process of their gradual adjustment to society, improve their own faculties, and in turn help society to prosper. The theory of social organism aims at the happiness of the individual, and in this differs from the theory of biological organism.Spencer's educational ideas were based on this sociological point of view. Man needs education in order to adjust to society. Education aims at equipping man for a perfect life, and for that end must endeavour to develop his mental and physical faculties in a well-balanced fashion. Moral education must be based on intellectual training. And the method of education should be such that would encourage an individual to use his capacities voluntarily to acquire knowledge.Spencer advocated an education which placed importance on the individual and which aimed at a harmonious adjustment of man to society.

1 0 0 0 OA エルヴェシウスの思想における「人間の科学」と「教育の科学」

- 著者

- 永冶 日出雄

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1965, no.11, pp.56-69, 1965-05-25 (Released:2009-09-04)

- 参考文献数

- 40

“A Treatise on Man, his intellectual faculties and his education” by Helvétius published in 1772 included an attempt to establish a science of education. It was a plan to build a new science concerning man, using methods of natural science.According to Helvétius, what formed man was not natural environment but social conditions, or rather “education” in a broad sence. In order to recognize the effects of such “education” and to improve it, a science of education was necessary. The aim of this science is none other than to establish a sound political system which would make possible ideal education for the young.The promotion of such a science would greatly benefit a country, since though power may temporarily impede the progress of education, society inevitably changes, and truth eventually will triumph as a thing most beneficial to man.

1 0 0 0 OA 吉田熊次先生の思い出

- 著者

- 海後 宗臣

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1965, no.11, pp.70-72, 1965-05-25 (Released:2009-09-04)

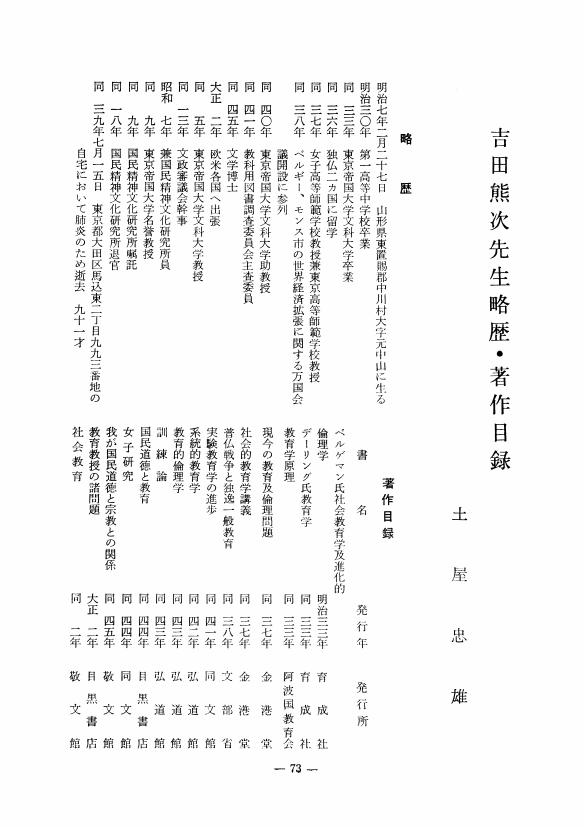

1 0 0 0 OA 吉田熊次先生略歴・著作目録

- 著者

- 土屋 忠雄

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1965, no.11, pp.73-74, 1965-05-25 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA J・H・ペスタロッチー全集 批判版Kritische Ausgabe

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1965, no.11, pp.75, 1965-05-25 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA デューイに関する最近の文献若干について

- 著者

- 杉浦 宏

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1965, no.11, pp.76-80, 1965-05-25 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA シュプランガーの政治教育思想

- 著者

- 村田 昇

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1964, no.10, pp.26-44, 1964 (Released:2009-09-04)

- 参考文献数

- 25

Eduard Spranger looked on the lack of political interest of the German people as an “hereditary defect.” Not only did he issue frequent warnings on the subject. He also exerted strenuous efforts to show how to overcome the defect. The roots of this defect he thought were to be found in the type of humanistic education which received its classic formulation by W. von Humboldt. He labored to discover a culture ideal for the new age by synthesizing the ideal of von Humboldt with that which by analogy he established as the ideal of political education, given its classic formulation by Frederick the Great. This work of Spranger gradually appeared in his demand for “political education.” What hemeant by “political education” was “education for country and for service to the totality, ” but this is not to be misunderstood as meaning blind servility to the nation-state or to the people. Spranger meant that under all circumstances education should be directed to acceptance of obligations in a spirit of freedom, with each individual conscious of his responsibilities and his position as an individual in a totality. In his thought, education was ultimately to be directed to nurturing an ethical and political attitude of spontaneity in the light of which men would shoulder their civic responsibilities according to their decisions made in good conscience before God. It is this kind of political education which I try to make clear in this essay.

1 0 0 0 OA シュプランガー博士の想い出

- 著者

- 荘司 雅子

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1964, no.10, pp.45-49, 1964 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA ボルノウにおける真理の本質

- 著者

- 川森 康喜

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1964, no.10, pp.50-67, 1964 (Released:2009-09-04)

- 参考文献数

- 54

今日論議の中心となっている真理問題には、「精密科学ならびに数学的論理学の形式化された真理概念」-この真理は公理の体系の中で矛盾していないことである-と、「純粋に主体的に人間存在へ関連させられた真理規定」-この真理は常にWahrheit für michである-との二つの立場があると考えられる。しかしここで取り上げられるのはいうまでもなくWahrheit fürmichの立場である。この立場は論者によってはプラグマティズムと実存哲学に妥当するとされるが、両者が等しくをWahrheit für michの立場にたつとしても、両者のもつそれぞれの真理の本質構造からみて、明らかに全く同一の真理構造をあらわすとはいえないだろう。しかしここでは主題の性質上プラグマティズムの真理の立場について詳しくは触れない。実存哲学の立場からというよりも、ボルノウの立場からこのWahrheit für michをめぐってそれの構造を分析し、それのもつ意味について明らかにしたい。一般的にWahrheir für michの図式で表わされる真理は、「主体性-真理」のカテゴリーで示され「真理は主体性である」ことを意味する。キェルケゴールの逆説的ないい方によれば「わたくしは真理である」という意味にもとられるだろう。しかし端的にいえばこのWahrheit für michは、わたくしに対する真理、いいかえるとわたくしと真理とのかかわりあい、即ちわたくしがいかに真理とかかわりあうかというように理解すべきである。それ故真理とは「何」 (Was) であるかが問われるのではなくて、むしろわたくしが真理と「いかに」 (Wie) かかわりあうかというわたくしの態度ないし仕方が問われるのである。このような真理の問われ方はまたボルノウの真理に対する根本的な態度でもある。したがってここで問題とされるのは「わたくしと真理とのかかわりあいの仕方」をボルノウが具体的にはどのような意味において受けとめているか、いわば彼における真理の本質についてである。ところでボルノウの真理追求の経過をみると、彼は精神科学の方法論的自立根拠を尋ねることでもって彼の真理問題の発想の拠りどころとした。自然科学とは異なった学的根拠を精神科学に求めること、即ち精神科学に独自な方法論的認識を尋ねることによって真理の本質に触れるのである。いいかえると精神科学の客観性を問うことによって真理の本質を追求する。しかも厳密にいえば後に明らかになるように、精神科学における真理の解明を通じて究極的には真理の実存的性格を明らかにするのである。精神科学は彼によれば、人間の生命に直接かかわる学であって、それの究極の狙いは人間生命の全体的関連を認識し明らかにするところにある。それ故精神科学の方法論的認識を問うことは、そのまま人間の生命の全体的関連における認識の機能を問うことになる。だから人間の生の形成をその究極の目的とする教育学が、自らの思考形式を精神科学の思考形式にその範を求めるとしても、なんら不当ではないだろう。もとより教育学が社会科学の範疇に属するか、それとも精神科学の範疇に属するかは今日の一つの問題である。しかし教育学の思考形式の一つを設定する意味において、われわれは精神科学の方法論的認識にアプローチすることに異議をもたないであろう。それ故この論文の主題はボルノウにおける真理の本質を解明するところにあるが、この解明を通じて教育学的思考ないし教育学の方法論的認識に対して一つの示唆を与えれば幸いである。

1 0 0 0 OA 『道徳教育研究法』

- 著者

- 小林 澄兄

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1964, no.10, pp.68-69, 1964 (Released:2009-09-04)

この本は、早稲田大学教授長谷川亀太郎氏の新著であって、道徳教育の意味・内容の研究法を明らかにすることを期したものである。

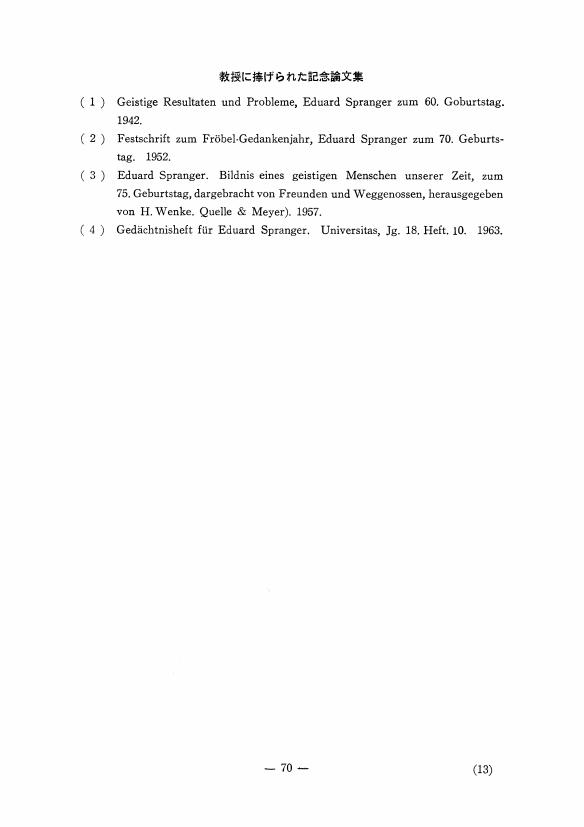

1 0 0 0 OA エドゥアルト・シュプランガー博士略歴と著作目録

- 著者

- 長井 和雄

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1964, no.10, pp.70-79, 1964 (Released:2010-05-07)

- 参考文献数

- 120

1 0 0 0 OA リット教授の想い出

- 著者

- 稲富 栄次郎

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1963, no.8, pp.121-123, 1963-06-25 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 故テオドール・リット博士略歴および著作目録

- 著者

- 鈴木 謙三

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1963, no.8, pp.124-146, 1963-06-25 (Released:2010-01-22)

- 参考文献数

- 261

1 0 0 0 OA 日本の道徳教育 (前篇) その世界観的基礎

- 著者

- 稲富 栄次郎

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1964, no.9, pp.1-19, 1964-04-30 (Released:2009-09-04)

- 参考文献数

- 9

It can be said that there is a generally accepted idea that the foundation of virtue (morals) lies in religion. Also, in the various countries of the West moral education takes place with religious education. In the public schools of France and America moral education is given by means of lessons in ethics and other ways, neither of which is unrelated to religion. Both directly and indirectly religion stands behind moral education.Consequently, if moral education in Japan is to be given according to the generally accepted notion of moral education, religion must lie at its foundation. However, because of the (present) educational situation and the actual historical state of our country, this is impossible. The question arises, “Where is Japan to look for its fundamental view of life ?” This article is about this problem and ways leading to a solution. Unfortunately, because of unavoidable cosiderations of space, only the prior part of the original plan is presented here.

1 0 0 0 OA 道徳的知性について

- 著者

- 浜田 俊吉

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1964, no.9, pp.20-37, 1964-04-30 (Released:2009-09-04)

- 参考文献数

- 36

The intellect can be considered one of the sources of morality. Long ago Aristotle listed it as one of the three requisites for a man to become a virtuous man. Thus the intellect is not only an important object of moral education, it is also clear that it is the effective fulcrum of education itself. This being the case what is the form (shape) by which moral intelligence expresses itself ; how can it be made to develop; and what is its function in relation to the totality of education ? These considerations will be the fundamental topics in any discussion about moral education.This brief paper, in response to these questions, considers the shape of the moral intellect appearing in the individual and in society. At the same time, as it is clear that the moral intellect deals with the personality itself and with man's entire value structure (as is not the case with other partial aspects of the intelict)

- 著者

- 高久 清吉

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1964, no.9, pp.38-56, 1964-04-30 (Released:2010-01-22)

- 参考文献数

- 47

According to Herbart the overall aim of moral education is thegrowth of the concept of morality. How does this amplification take place ? With this consideration in mind Herbart tells us that he directed his attention to the necessary premiss of the concept of morality and concluded that it was Geschmacksurteil (taste judgement). The first half of this paper surveys the originality which underlies Herbart's moral system and gives the gist of his theory.In the second part of this paper, by means of Natorp's criticism of Herbart, attention is focused on this taste theory, and the characteristics of Herbart's logic are investigated more closely. Natorp summarizes the essence of this logic as one that denies the autonomy of the moral will since morality founded on taste is a morality founded on feeling. Herbart replies to Natorp's criticism and concludes that it is not to the point to say that it is (mere) feeling. He emphasies moral freedom and rationality since the essence of taste-judgement is something rational, not merely sensible.

1 0 0 0 OA 道徳教育文献年表

- 著者

- 原田 茂

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1964, no.9, pp.57-67, 1964-04-30 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA ヤスパースにおける教育の二律背反性

- 著者

- 小川 克正

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1964, no.9, pp.68-83, 1964-04-30 (Released:2009-09-04)

- 参考文献数

- 14

Man's existence is restricted by an antinomy-it is an existence which is temporally in via. To be a man (Menschsein) and to become a man (Menschwerden) - between these two states-lies a limitless distance and an endless number of problems. Education fof the fundamental direction of man, if it possible for him to be a man, will be restricted by the structure of this antinomy. That is to say, it must take place amid polarities which involve contradictory opposition and relations of strain -i. e. self and society, interiority and exteriority, eternal and temporal, freedom and authority.Formalistic education which treats man as a simle object (a technical production education) is opposed to Socratic education by communication. The latter takes hold of the roots of freedom in various and diverse individuals and at this point begins its appeal to reason in attempting to lead a person to open his eyes to self. True education takes its place between these two extremes. True education, while esteeming man's freedom and existential status, also considers the actuality of his being restricted by society. This antinomy is the framwork which not only makes possible true education but also sets the limits of directive education.