1 0 0 0 OA 日野・トヨタ提携の史的考察

- 著者

- 塩地 洋

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.23, no.2, pp.59-91,iii, 1988-07-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

- 被引用文献数

- 1

This article provides an historical analysis of the relations between the Toyota Motor Company and Hino Motors Limited, relations which formally began in 1966. Through such analysis, light can be shed on the general characteristics of tie-ups between vehicle manufacturers.Three basic areas are covered. First, Hino's failure in the small automobile sector is discussed. In the 1950's Hino was a specialist manufacturer of large trucks and buses. In 1961, it tried to enter the small car sector but, faced with severe competition, made an ungraceful exit and was left with a large investment in small car assembly equipment.Second, the tie-up with Toyota is examined. Through this tie-up, Hino was restored to its former position as a specialist in the large truck and bus field, and Toyota was able to utilize Hino as a subcontracting assembler of Toyota brand automobiles. This arrangement was good for both companies. Partly because of the benefits of specialization, Hino's market share gradually rose and it eventually reached the top position in its sector. For its part, Toyota was able to increase production through the subcontracting arrangement.Finally, the shift in the nature of the tie-up is considered. In the 1970's, as Japan's economy moved from high to low growth, the domestic demand for large trucks and buses began to stagnate and Hino suffered as a result. At the same time, needless to say, Toyota increased small car production through the expansion of both domestic and export markets.In general, this episode points out some of the long term factors involved in selection and bargaining between partners in vehicle manufacturing tie-ups.

1 0 0 0 OA 昭和初期日本の新聞用紙カルテルと外紙輸入 -外紙ダンピング論の再検討を含めて-

- 著者

- 四宮 俊之

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.23, no.3, pp.1-28, 1988-10-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

- 被引用文献数

- 1

In Japan, the newsprint manufacturers founded a cartel for the cooperative sales of newsprint in 1901. It intended to control the domestic market. But the newspaperdom succeeded to curtail the import duties on newsprint in 1906, and so sometimes was able to import cheaper foreign-made newsprint easily. Consequently, the cartel couldn't control the market satisfactorily.Under those market structures, plenty of cheap newsprint began to be imported from Northern Europe and Canada after 1930; it was regarded, especially about the Canadian newsprint, as dumping among the Japanese persons concerned in those days, and it induced industrial reorganization of Japan's paper manufacturing in 1933.But that commonly accepted understanding as dumping overlooked the influence of exchange fluctuation of those days. As the concluding remarks, after the Japan's lifting of the gold embargo in 1930, yen revaluation served to reduce the yen basis imported prices. So the importation wasn't dumping. But after the final gold ban in 1931, yen devaluation didn't raise prices, because several foreign manufacturers began to dump on the Japanese market. However the dumping was begun after the informal decision of the above-mentioned industrial reorganization.

- 著者

- 許 紫芬

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.23, no.3, pp.29-47, 1988-10-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

1 0 0 0 OA ドイツ経営史研究の動向 -西ドイツを中心に-

- 著者

- 加来 祥男

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.22, no.4, pp.52-82, 1988-01-30 (Released:2010-11-18)

1 0 0 0 OA 一九八二年の外国経営史

- 著者

- 原 輝史

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.22, no.4, pp.83-90, 1988-01-30 (Released:2010-11-18)

1 0 0 0 OA 一九八三年の外国経営史

- 著者

- 壽永 欣三郎

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.22, no.4, pp.90-94, 1988-01-30 (Released:2010-11-18)

1 0 0 0 OA 一九八四年の外国経営史

- 著者

- 安部 悦生

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.22, no.4, pp.95-101, 1988-01-30 (Released:2010-11-18)

1 0 0 0 OA 一九八五年の外国経営史

- 著者

- 塩見 治人

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.22, no.4, pp.101-108, 1988-01-30 (Released:2010-11-18)

1 0 0 0 OA 大正中期民間企業の技術者分布 -重化学工業化の端緒における役割-

- 著者

- 内田 星美

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.23, no.1, pp.1-27, 1988-04-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

- 被引用文献数

- 1

According to a statistical survey of graduate engineers from universities and technical colleges, the total number of engineers in Japan in 1920 was 1, 400, 2.8 times as many as ten years earlier; of these 73% were employed in private industry. Employment in metal, electrical, chemical and engineering industries marked 5-13 times increases in ten years, indicating the rise of heavy and chemical industries during the First World War.Seventy firms, of which 20 were founded between 1910 and 1920, employed more than 20 engineers, against 20 firms in total in 1910; and 11 firms employed more than 100. Increasing the number of engineers within a firm would naturally lead to the ordering of engineers by age.Thirty-six large firms hired engineers in specific subjects who had graduated almost every year from 1905 until 1919, suggesting the origin of the “Japanese management” practice of employing freshmen each year and letting them climb up the ladder of positions.More than 100 firms had several engineers in top management with the title “manager” or “chief engineer”; most of them had graduated during the 1890's, although few of them had seats on the board with their capitalist employers.Recently established steelmaking or shipbuilding companies had recruited veteran engineers through transfer from related Zaibatsu firms or through head-hunting from public or private concerns.For the first time in Japanese business history, several firms erected laboratries during the war. These firms were employing young physicists and chemists who had graduated from science faculties of the universities in addition to engineering faculty graduates.

1 0 0 0 OA 第一次大戦期における三菱合資の海外支店 -ロンドン支店を中心に-

- 著者

- 長沢 康昭

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.23, no.1, pp.28-51, 1988-04-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

During World War I, Mitsubishi Goshi opened branches in Europe and America for the company's overseas activities. In this paper, I have analysed the motives, activities and the results of such development by focusing on the London Branch in England.Before the war, the company had its foreign branches only in China, and most of the overseas activities had been conducted through foreign commercial houses. When the war occurred, the company felt it difficult to export to Europe, so the company switched its export trade from Europe to Russia via Vladivostok. But again, as Russia suspended gold standard, the company faced another difficulty to take foreign exchange risk. Since the company had to import goods such as machinery or raw materials, it was indispensable to promote export for acquiring a steady supply of foreign currency. In order to meet such needs, the company opened its branch office in London 1915 and New York the next year.The London Branch sold the company-made non-ferrous metal such as copper or Chinese products, and purchased machineries and materials for the company's shipyard. The accounts for these transactions were settled by the foreign exchange in the firm. The purchasing was soon exceeded by selling, so a trade surplus was accumulated in the branch office. With the purpose of making use of these surplus funds, the company went into the common exchange business. On the other hand, Japan was enjoying a war boom, and the Trading Division of Mitsubishi Goshi decided to add other company products to its own line; thus the company turned to a general trading enterprise. With corresponding to such a transformation, the company decided to enlarge the scope of overseas activities, resulting in the opening of agent offices in such cities as Paris, Seattle, Berlin, Rome, Lyon and Marseilles.These activities of the foreign branches became a precondition for further growth of the foreign exchange business of the Bank Division as well as of the proper business of the Trading Division of Mitsubishi Goshi. Later the foreign exchange business of these branches was transferred to Foreign Exchange Division of Mitsubishi Bank, and their trading business was to Mitsubishi Shoji (Trading) Company.

1 0 0 0 OA 中上川入行前後の三井銀行

- 著者

- 粕谷 誠

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.22, no.3, pp.29-55,ii, 1987-10-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

- 被引用文献数

- 1

The amount of deposits of Mitsui Bank increased rapidly after 1886, leading to a corresponding increase in the amount of loans by the bank. In spite of these favorable circumstances, the bank had held a lot of bad loans because it lacked the ability to review requests effectively. T. Masuda, president of Mitsui Bussan Kaisha, was anxious about the state of Mitsui Bank. He asked K. Inoue, the former Minister of Finance, for help and advised T. Nishimura, vice-president of Mitsui Bank, to place more effort at loan collection. But Nishimura didn't translate Masuda's advice into action, as he was a man of indecision. Consequently, Mitsui Bank lost the confidence of bankers and the amount of nongovernmental deposits decreased from 17, 117 thousand yen to 12, 612 thousand yen in the first half of 1891. Masuda complained to Inoue that Nishimura could not cope with the crisis of Mitsui Bank. Then Inoue asked H. Nakamigawa, president of Sanyo Railway Company, to enter Mitsui Bank and institute reforms. Nakamigawa entered Mitsui Bank in August 1891. He collected outstanding loans to Higashi-Honganji and recieved collateral from other borrowers. But I think it must be emphasized that Mitsui Bank had already been recieving collateral prior to Nakamigawa's entry and that he wrote off bad loans by reducing reserve fund which had been maintained since the bank's establishment in 1876. (It had several kinds of voluntary reserve accounts because its financial status in 1876 was very bad.) He was able to pay back the bank's borrowings from the Bank of Japan by the end of 1892 because the bank's deposits had increased and the amount of governmental bonds which it held decresed.

1 0 0 0 OA 〈年間回顧〉

- 著者

- 麻島

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.22, no.3, pp.56, 1987-10-30 (Released:2010-05-07)

1 0 0 0 OA 一九八二年の日本経営史

- 著者

- 長沢 康昭

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.22, no.3, pp.57-62, 1987-10-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

1 0 0 0 OA 一九八三年の日本経営史

- 著者

- 中村 青志

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.22, no.3, pp.62-71, 1987-10-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

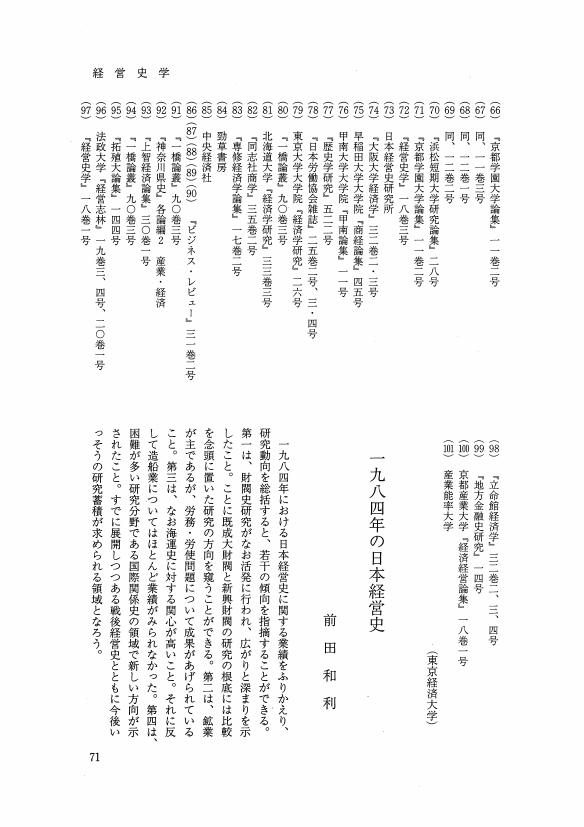

1 0 0 0 OA 一九八四年の日本経営史

- 著者

- 前田 和利

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.22, no.3, pp.71-79, 1987-10-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

1 0 0 0 OA 一九八五年の日本経営史

- 著者

- 四宮 俊之

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.22, no.3, pp.79-89, 1987-10-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

1 0 0 0 OA 造船企業の社史についての一考察

- 著者

- 柴 孝夫

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.22, no.3, pp.90-104, 1987-10-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

1 0 0 0 OA 米国鉄道企業の賃金管理 -バーリントン鉄道の「等級制度」を中心にして-

- 著者

- 大東 英祐

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.22, no.4, pp.1-30, 1988-01-30 (Released:2010-11-18)

In the early days of railroading, locomotive engineers were recruited from among mechanics. It was a great recommendation if they had worked for a locomotive manufacturer. They were paid by day, in the same way as mechanics were. Since mechanic turned engineers were skilled in the two trade, they tend to be too proud to be obedient to orders. In the 1870s, however, many railroads including the C.B. & Q. introduced new methods of wage payment, such as the trip system and classification system. At the C.B. & Q., R. Harris introduced a new method by combining the two mentioned just above on Sept. 1, 1876 and reduced wage rates on June 10, 1877. Under the new method, engineers were graded into the four classes in terms of the length of the service which were paid accordingly. Judging from remaining company records, this was due partly to the financial pressure of the prolonged depression of the 1870s. The work can be done for less money than before, by replacing the first class men with the second and the third class men with lower wage rates. However, we must not ignore the long term significance of the new method, under which in order to climb up to the first class one has to be promoted step by step every year. In other words, the method was inseparably tied with the policy of promotion from within. On Nov. 20, 1884, Mr. Rhodes, the superintendent of the motive power, send a circular letter to all the master mechanics of the company instructing “Hereafter please do not employ engineers and firemen who had worked on other roads… In doing otherwise, we are likely to import the bad elements of other roads.” And by the middle of 1880s, the company had developed well a designed employment practices, by which it had attained self-sufficiency in well trained engineers. It goes without saying that this is a great achievement. At the same time, however, it bred discontent among engineers and their brotherhood and caused a bitter strike in 1888.

1 0 0 0 OA フランス経営史研究の動向 -最近一〇年間を中心に-

- 著者

- 原 輝史

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.22, no.1, pp.30-61, 1987-04-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

1 0 0 0 OA 鉄鋼企業史の一考察

- 著者

- 岡崎 哲二

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.22, no.1, pp.62-70, 1987-04-30 (Released:2010-02-19)