1 0 0 0 OA TAXATION IN EGYPT UNDER THE ARAB CONQUEST

- 著者

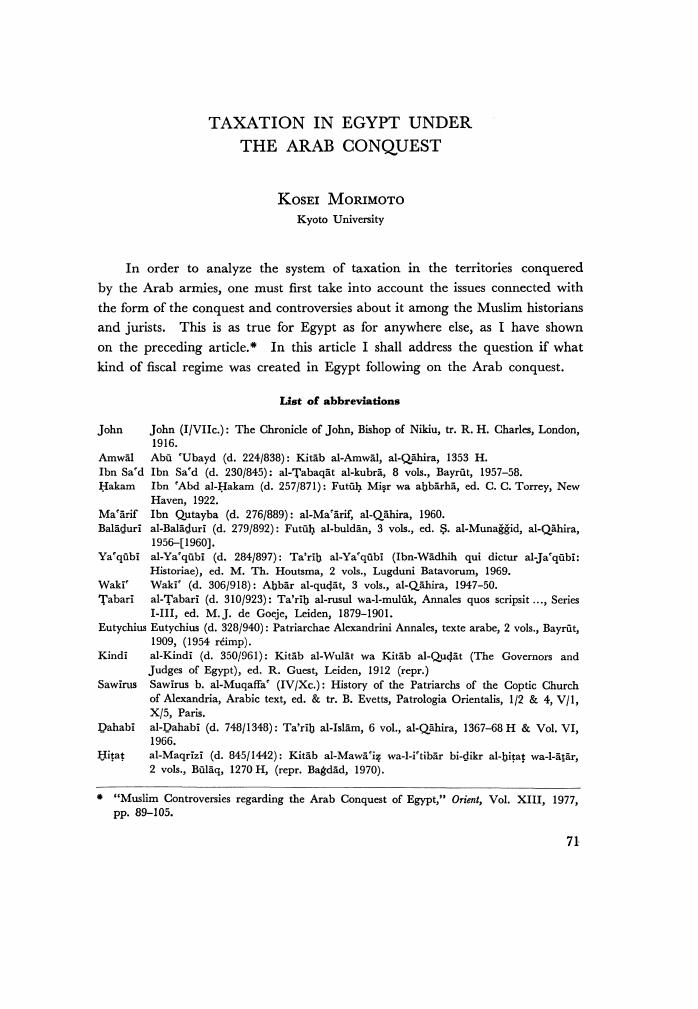

- KOSEI MORIMOTO

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- Orient (ISSN:04733851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.15, pp.71-99, 1979 (Released:2009-02-12)

- 参考文献数

- 91

- 著者

- Sachiyo KOMAKI

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- Orient (ISSN:04733851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.42, pp.71-93, 2007-03-31 (Released:2014-07-08)

- 参考文献数

- 15

- 被引用文献数

- 1

In South Asia, many mosques and shrines carefully preserve Islamic holy relics. A large proportion of them are articles which are believed to have belonged to the Prophet Muhammad and the rest are deemed to have belonged to his family, his companions or later renowned Muslim saints. Here I consider the cult of Islamic holy relics from an anthropological perspective, based on the theme of the “succession of holiness.” Most of the holy relics open to the public are accompanied with a storied history in which dynastic rulers and renowned saints make an appearance. In this sense, the succession of holy relics is intimately connected with politics. However, the holy relics are also tangible objects that strongly arouse feelings of respect and affection for the Prophet, as well as act as a reminder of his life and times. It is likely that those who view the relics perceive umma or all Muslims, rather than a specific individual or group, as the successor to the relics. Herein lies an imaginative world, or poetics, concerning the succession of holy relics. Meanwhile, relatively inexpensive charms and amulets based on the motifs of certain holy relics are being circulated as souvenirs from holy places. This phenomenon, whereby holy relics in the form of charms and amulets are brought into an individual's private domain and venerated, means that they are also being passed down among the general populace. I would like to call this the pop aspect of the succession of holy relics. This paper considers from the above perspectives the aspects of politics, poetics and pop in thesuccession of holy relics based on my fieldwork in South Asia, in particular in North India and Pakistan.

- 著者

- 小板橋 又久

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- オリエント (ISSN:00305219)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.26, no.2, pp.45-60, 1983

The verb <i>šr</i> (*šyr) is the major term which denotes "to sing" in Ugaritic. This term occurs several times in the alphabetic texts of Ugarit. To describe the singing as reflected in those Ugaritic texts is my purpose. This paper deals with <i>KTU</i> 1.23, 1.16, and 1.112.<br>Here are the problems. In which scenes do these singings appear? Is there any similarity among those singings? What can we conclude about musical life from examining those Ugaritic texts?<br>Our conclusions are as follows. <i>KTU</i> 1.23: 12 seems to be a rubric in a ritual drama which states that something is to be recited 7 times and the '<i>rbm</i>, who is a kind of personnel in cultic ritual, is to respond. In <i>KTU</i> 1.106: 15-17, after the sacrifices are dedicated to the various gods, the singer (<i>šr</i>) sings 10 times in front of the king and then the king opens his hand. In <i>KTU</i> 1.112: 17-21, on the 14th day of a fixed month, when the <i>gtrm</i> gods go down to the sacrifices, the <i>gtrm</i> respond to somebody and then the <i>qdš</i> priest sings a song. The singing of <i>KTU</i> 1.23 occurs in one of the scenes of a ritual drama, and that of <i>KTU</i> 1.106 occurs together with the performance of a prayer which is given in the ritual of a fixed month. The singing of <i>KTU</i> 1.112 may occur in the oracle We can find a few similarities among those singings. Firstly, those singings occur in a cultic ritual. Secondly, those singings are connected with the gods. Thirdly, we may discover here that the meaning of the singing is man's asking favor of the gods. Thus we might conclude that cultic personnel sang a song in the various scenes of the rituals performed in the Ugaritic kingdom for the purpose of asking favor of the gods.

- 著者

- 永井 正勝

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- オリエント (ISSN:00305219)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.53, no.2, pp.34-54, 2011

The sentence apearing in lines 74-75 of <i>P. Hermitage No. 1115</i> has been understood as a negative construction of a progressive sentence, <i>nn sw ḥr sḏm</i>, in many studies. This understanding is based on an assumption that the sign A1 tn the original text is so wrongly written that we should omit it or should emend it to A2. In this way, the transcription <i>nn wi ḥr sḏm st</i> is derived.<br> However, in my opinion, the sign A1 in the original papyrus is the 1st person suffix pronoun<i>=i</i> and the text should be understood as a sentence with an adverbial predicate, <i>nn wi ḥr sḏm=i st,</i> "I am not in the situation that I hear it." In this sentence <i>sḏm=i st</i> is thought of as an unmarked complement clause.<br> As not even one correct example of the <i>nn sw ḥr sḏm</i> has been attested, I would like to propose that this constriction is a ghost form invented by modern scholars. As a result, the paradigm of the imperfective aspect, including the progressive form, would look like this:<br><br> imperfective aspect (intransitive)<br> habitual progressive<br> affirmative <i>iw(=f) sḏm=f </i><i>iw(=f) ḥr sḏm</i><br> negative <i>n sḏm.n=f</i>

1 0 0 0 モンゴル時代におけるペルシア語インシャー術指南書

- 著者

- 渡部 良子

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- オリエント (ISSN:00305219)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.46, no.2, pp.197-224, 2003

- 被引用文献数

- 2

In the history of the Persian art of <i>insha</i>' (the epistolary art for the official and private correspondence), the Mongol period (from the 13th century to the later 14th century) has been regarded as an age of stylistic regression between the Saljugid and the Timurid periods. This report, through the analysis of some Persian <i>insha</i>' manuals written in the Mongol period, throws light on the continuity and development of the Persian <i>insha</i>' tradition under the Mongol rule, and how it coexisted with the Mongol chancellery system.<br>In the <i>insha</i>' manuals of the Mongol period, it is observed that the way of Persian letter-writing had become more complicated since the Saljugid period. The structure of ideal letters explained in some manuals in the 14th century was more fractionalized than that in those of the 13th century and very similar to the style in the Timurid period. Even some forms that had been considered incorrect became predominant during the period in order to show extreme respect to distinguished addressees.<br>Even under the rule of the Mongol chancellery, the writers of <i>insha</i>' manuals kept the traditional forms of drafting official documents, concentrating on genres of documents which needed the literary skill of <i>insha</i>', like deeds of appointment to religious ranks. At the same time, for many literates, writing of <i>insha</i>' manuals was regarded as a suitable way to display their literary skill and to win their patrons' favor.<br>On the other hand, the <i>insha</i>' writers understood some concepts of the Mongol chancellery in the context of their own <i>insha</i>' tradition and accepted a portion of them positively. For example, the practice of Mongol edicts of writing words with holy or royal referents jutting into the upper margin was very agreeable for them because of its similarity to the convention of Persian letter writing that the name of honorable persons must be written in the upper part of letters. They adapted it by writing honarable words jutting into the right margin.<br>We can conclude that under the Mongol rule the Persian <i>insha</i>' tradition continued developing and prepared for the flowering of the art in the Timurid period.

- 著者

- 土谷 遥子

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- オリエント (ISSN:00305219)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.53, no.1, pp.120-143, 2010

Evidence points to Pouguch in the Darel Valley as the most likely site of T'o Leih(陀歴) where Fa Hsien paid a tribute to the gigantic wooden Maitreya Buddha image, 24 meters tall. Fa Hsein described, "The Maitreya image was emitting an effulgent light on fast days and the kings of the surrounding countries vie with one another in presenting offerings to it."<br> Pouguch can be characterized as a temple site lacking defensive measures. The walls are of red mud. A mound probably remnants of the main temple, is centrally located. The site is near the mouth of the Darel Valley, far from the valley entrance which is at its opposite end.<br> Interviews with Pouguch villagers were conducted since their folklore is considered to have remained unadulterated due to the long isolation of the valley, a result of geography as well as xenophobic and violent uprising. Men varying in age from 20s to 70s and from various walks of life: farmers, engineer, scholar and official, were asked what they heard of the Pouguch site. Their stories are strikingly akin to what Fa Hsien observed in T" Leih in 401 A. D.; 1) a major Buddhist temple of worship and learning, attracting pilgrims from Central Asia, China and Tibet, 2) contained an image of Buddha, 3) the image was made of wood, while solid gold, was also mentioned, probably mistaking the gold hue emitting effulgent light, 4) the image was colossal ; one person correctly stated 24 meters in height.<br> The verbal tradition in Pouguch which has been passed down largely intact over 1600 years suggests the idea that Pouguch Site be the T'o Leih that Fa Hsein visited.

- 著者

- GOTO Toshifumi

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- Orient (ISSN:18841392)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.39, pp.122-146, 2004

Yasna 9 forms the main part of the text known as "Hom-Yašt" (Y9, 10, and 11, 1-12), the worship of Haoma, which must have been forbidden by Zaraθuštra himself. In order to gain insight into prehistory of the Haoma- Soma cult, the text is remaining still to be studied as a main source. It is written in a standard style of Young Avestan, and its investigation will contribute to establish the Avestan grammar more precisely. This article deals with the form and use of verbs in Yasna 9:<BR>1. Preterit forms without augment: 1.1 ∂r<SUP>∂</SUP>nauui; - 2. Y 9, 15, and the augmented forms: 2.1. apataii∂n, and the antecedent past; 2.1.1. Y 9, 11 araoδat; 2.2. Y 9, 15e-h; 2.2.1.abauuat, confirming statement; 2.2.2. Avestan forms in the function of confirming the facts in the past; 2.2.3. "injunctive" as (?); 2.2.3.1. Old Avestan as, ahuua; 2.2.3.2. Yt 10, 9; 2.2.4. Y 9, 15h damqn; 2.2.5. upait Y9, 1a-d; - 3. Y 9, 22.23, and the subjunctives: 3.1.ae<SUP>i</SUP>biš, +baxša<SUP>i</SUP>te; 3.2. taxš∂nti, +baxša<SUP>i</SUP>te, baxša<SUP>i</SUP>ti, anh∂nte, subjunctive in the gnomic period; 3.3.azizana<SUP>i</SUP>tibiš; - 4. Y 9, 24, raosta, the resultative inj. aor.; - 5. Y 9, 5, fracaroiθe, xšaiioit; - 6. dauuq<SUP>i</SUP>θiiå Y 9, 18. - (Injunctive of the "stative" verbs n.3; Instrumental P1. 3.1., 3.3., n. 57.)

1 0 0 0 セミラミスと西王母

- 著者

- 森 雅子

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- オリエント (ISSN:00305219)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.31, no.1, pp.148-160, 1988

1 0 0 0 ガーサー語彙の研究

- 著者

- 伊藤 義教

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- オリエント (ISSN:00305219)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.9, no.1, pp.1-21,89, 1966

In Gathica 1. <i>xšmavato</i>, the present writer has come to the conclusion that <i>xšmavato</i> should be taken as nom., voc. or acc. P1. of <i>xšmavat</i>- "Your Highness", and not as abl. -gen. sg. of <i>xšmavat</i>- "resembling you, your-like, your adherent" (adj.) as is generally accepted. See my paradigm (p. 5.) of all the pronominal stems suffixed with -<i>vant</i>-. —In Gathica 2. <i>aka</i>, rejecting all of the interpretations proposed thus far, the present writer has pointed out the fact that the Gathic <i>aka</i> has retained its primordial meaning "to show, make clear", so that it may be regarded as an infinitive (abl. -gen. sg. of <i>aka</i>-) "in order to show, for showing". It is only in yAv. that what is meant by <i>aka</i> came near to what is meant by Pahl. <i>akas</i> "clear, evident". —In Gathica 3. <i>manaroiš</i>, the writer has derived <i>manari</i>-from <i>mru</i>-/<i>mrav</i>- (Skt. <i>bru</i>-) "to speak" (<i>mru</i>->[after the pattern of <sup>3</sup><i>dar</i>-><i>dadari</i>-] <i>mamravi</i>->[with the metathesis of <i>ra</i>><i>ar</i> prior to <i>aui</i>><i>aoi</i>] <i>mamarvi</i>->[with the assimilation of <i>v</i> to <i>i</i> in <i>vi</i>><i>yi</i>]<i>mamaryi</i>-><i>mamari</i>->[with the dissimilation of <i>m</i>><i>n</i>]<i>manari</i>-). The hapax <i>manaroiš</i> (Y. 48<sub>10</sub> a) would then mean "away <i>or</i> separating from crying".<br>The translation of several passages should suffice as examples showing my interpretation.<br>Y. 44<sub>1</sub>, <i>bc</i>: "By-virtue-of-(my)veneration—such-as the veneration (in general should be)—, o Your-Highness (<i>xšmavato</i>), o Mazda-, may Thy-Highness (θ<i>wavas</i>) tell to (Thy) friend, i. e. to myhumble-self (<i>mavaite</i>)!"<br>Y. 51<sub>13</sub> <i>bc</i>: "(the <i>dregvant</i>) whose soul shall become angry at (him) at the Cinvat Bridge, in order to show (<i>aka</i>) (thus): 'With the deed of (thy) own as well as of (thy) tongue thouhast-gone-astray from the way of justice'."<br>Y. 50<sub>2</sub> <i>cd</i>: "Those-living-rightly with justice among the many keeping off the sun —in order to show them (<i>akasteng</i> i. e. <i>akas teng</i>) mayest Thou make me arrive at the gifts of givers!"<br>Y. 48<sub>10</sub> <i>a</i>: "When, o Mazda, shall the warriors attend-the-sacrifice, separating-from-(their) crying (<i>manaroiš</i>)?" that is, "The warriors are now adhering to the old cult in which cry is raised to kill the ox. When shall they separate from such a religious custom in order to attend our newly established cult?"

1 0 0 0 大塚和夫さんのご逝去を悼む

- 著者

- 赤堀 雅幸

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- オリエント (ISSN:00305219)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.52, no.1, pp.165-168, 2009

- 被引用文献数

- 1

1 0 0 0 マニの啓示にあらわれた"仲介者"の観念

- 著者

- 須永 梅尾

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- オリエント (ISSN:00305219)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.19, no.2, pp.69-84,203, 1976

We shall come across the Manichaean texts of the Middle Persian, Coptic, Greek, and Arabian. In these texts specially we find several words, Nrjmyg, SAIŠ Συζυγος, Tawm as the Mediator between the Father of Light and the Apostle (Mani). The six translations of these words is (1) Twin or Pair, (2) Familiar, (3) Double, (4) Companion, (5) Consort, (6) Angel. The texts about these words is the Middle Persian fragmentary texts "M49 II", Coptic texts "Manichäische Homilien", "Manichaean Psalm-Book" and "Kephalaia" and new Greek texts "Kölner Codex".<br>From these texts I may conclude that the Twin as the Mediator of Mani was angelic. As to this conception of the Mediator there are some difference between his first and second revelation. Above all, in the period of the second revelation, the conception of the Mediator changed from Angel to Twin or Pair-Companion.<br>When he entered upon his mission, the so-called three books in the canon were already completed. He said to his disciples: "the Pragmateia, the Book of the Secrets and Book of the Giants are gifts bestowed (written) by the Twin of Light. Other books in the canon is the Great Living Gospel given by the Envoy and the Treasure of Life given by the Column of Glory." Namely the two books was given by Mediators as Iranian "Manvahmed vazurg (the Great Nous)", and came later.<br>Therefore the revelation in the three books and other both books each reflects the change of the religious thought of Mani. The former represents his early idea, the latter his later idea.<br>I may conclude that the conception of the Mediator in the revelation of Mani changed gradually from the Jewish Christian or Mandaean Gnosis to the Iranian Gnosis (Twin→the Great Nous.)

1 0 0 0 ナスィール・ウッ・ディーン・トゥースィーの生涯と業績

- 著者

- 黒柳 恒男

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- オリエント (ISSN:00305219)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.9, no.2, pp.163-186,232, 1966

- 被引用文献数

- 1

It is noteworthy that the verdict given by Orientalists on the medieval Persian erudite scholar Nasir al-Din Tusi has changed in the course of time, especially after the Second World War. Before the War, he used to be condemned for his treachery to his master and the part played by him in the fall of Baghdad. But, on the contrary, after the War he is sometimes regarded as a benefactor to the renaissance of Islamic culture.<br>So in this article the writer intends to re-examine his life at a crucial time through the following periods:<br>(1)-His connection with the Ismailites.<br>(2)-The role played by him in the fall of Baghdad.<br>(3)-His academic activities in Maragheh.<br>In conclusion his value should be estimated, not from the viewpoint of his political career, but from the standpoint of his great contributions to the re-birth of Islamic civilization after its destruction by Mongols.

1 0 0 0 ペルシア文学におけるジャムの酒杯

- 著者

- 黒柳 恒男

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- オリエント (ISSN:00305219)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.17, no.2, pp.87-100,184, 1974

Jam-e Jam which means Jamshid's Cup, is one of the most traditional and favourite themes among the classical Persian poets. This Cup has been expressed in various names, such as Jam-e Kai Khosrou, Jam-e Jahan-numa, Jam-e Giti-numa, Jam-e Jahan-bin, Jam-e Alam-bin, Jam-e Jahan-ara, Jam-e Iskandar and Aine-ye Soleiman. Ferdousi, the greatest Persian epic poet, was the first one who used this Cup in his Shahname. He called it Jam-e Gitinumayi, which means the Cup representing the whole world, by which King Kai Khosrou found out the missing hero Bizhan. After this, this Cup was called Kai Khosrou's Cup until the twelfth century and many famous poets, such as Unsuri, Masud-e Sad-e Salman, Muizzi and Khaqani used this Cup in their poems in the traditional and mythical way.<br>But after the twelfth century, this Cup began to be called Jam-e Jam and was employed as a mode of Sufi expression. The famous Sufi poet Sanai interpreted this Cup for the first time as Sufi's pure heart in his Tariq al-Tahqiq. After him many Sufi poets, such as Attar and Sadi adopted his interpretation. This Cup found its highest expression in Hafiz's ghazals, in which he expressed this Cup in different ways and meanings. The true understanding of this term is regarded as an important key to appreciate his implicative poems.<br>In short, we may conclude from the use of Jam-e Jam in Persian literature that Persian poets who flourished in the Islamic periods were greatly influenced by their pre- Islamic traditions, wherein we make out the Persian cultural continuity and consistency.

- 著者

- INOUE Koichi

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- Orient (ISSN:04733851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.41, pp.21-40, 2006

This article presents the political function of the Holy Face of Edessa. one of the most important relics in the Christian world: how it was exploited for imperial legitimacy.<br> In August 944 the Image of Edessa was brought into Constantinople as the fruits of Romanus Is campaign against the Muslims in Syria. The <i>adventus</i> ceremony of the holy image was performed solemnly so that it might miraculously heal the old Emperor of his illness. Romanus I, a usurper, also hoped that the relics would purify his usurpation of the crown from Constantine VII ofthe Macedonian dynasty.<br> In December 944, however, Romanus was forced to abdicate and brought into a monastery. Returning to the throne, Constantine VII also used the holy image as a demonstration of his legitimacy. Under his direction the court intellectuals rewrote the history of the acquisition and the <i>adventus</i> ceremony of the holy image: they insisted that the image celebrated Constantine VII.<br> The most important point to be noted in this article is that the <i>Narratio de imagine Edessena</i>, a history of the Image of Edessa composed at the court of Constantine VII, repeatedly emphasized the images protection of the city of Constantinople. The special emphasis on the Capital City formed a part of the Macedonian dynastic propaganda that the dynasty was related to Constantine the Great, the founder of Constantinople. The Image o f Edessa was hence closely involved in the dynastic politics o f the Byzantine Empire as a <i>palladium</i> of Constantinople.

1 0 0 0 ガバザ, アドゥーリス, コロエー:「アクスムヘの道」検証の試み

- 著者

- 蔀 造勇

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- オリエント (ISSN:00305219)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.49, no.2, pp.133-146, 2006

The route from Adulis to Aksum must have been the most important in East Africa in ancient times. Adulis was the most important town on the coast and Aksum was the center of a rather important empire, starting about the time of Christ and lasting until the eighth or ninth century.<br>What was the course of the route from Adulis up into the mountaneous country of what is now Ethiopia and Eritrea? The <i>Periplus of the Erythraean Sea</i> refers to a location named Koloe, a city 'that is the first trading post for ivory' and says 'from Adulis it is a journey of three days to Koloe.' This article seeks to identify the location of Adulis and its harbor Gabaza, and to locate the route from Adulis to Koloe. The author analyzes historical sources and archaeological data. The information obtained from his field survey is also used to explain some topographic problems.<br>The conclusions of this paper are as follows:<br>1. The equation of Adulis of the <i>Periplus</i> with a site situated some 1km to the northnorthwest of the modern village of Zula is acceptable.<br>2. Didoros Island of the <i>Periplus</i> of the first century was situated on the same spot as Gabaza mentioned in the 6th century sources.<br>3. Some 5km to the southeast of Adulis site are some hills named Gamez 100 years ago, but now known as Gala/Galata. Didoros Island is identified with one of these hills and Gabaza harbor must have been situated at the foot of it.<br>4. There has been major coastal change in the area. For this reason the island of Didoros approached by a causeway in the first century was situated on the shore in the sixth century and it lies now as a hill some 1km away from the shore.<br>5. The course of the route from Adulis to Koloe identified with modern Qohaito must has been through the Wadi Komaile rather than the Wadi Haddas.

- 著者

- 田中 穂積

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- オリエント (ISSN:00305219)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.12, no.3, pp.43-56,222, 1969

We cannot discuss the meaning of Hellenism in the eastern Hellenistic world without considering the activity of the Greek city. In pursuing this subject, we must consider how the Greek colonies built by the early kings of the Seleucids changed into real cities; but we cannot say which of the colonies were originally military and which were civil settlements. Many of them, of course, developed under the impetus of the expansion of the Hellenistic economic sphere. And we understand also that they were recognized as Greek cities by Antiochus III in connection with the general political situation both within and without the Seleucid realm. But material for the study of the Greek city in the east is imperfect. Therefore I re-examine the letter sent to Magnesia on the Maeander from Antioch in Persis (OGIS 233), the import of which is related to the festival of Artemis Leucophryene at Magnesia; the letter includes many problems: the relations of the Greek city in the east to the kings of the Seleucids and the Greek city on the western coast of Asia Minor, and the mutual connections between the Greek cities in the east. In this article I try to examine especially the extent and nature of Hellenism in the east.

- 著者

- 永井 正勝

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- オリエント (ISSN:00305219)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.53, no.1, pp.161-166, 2010

- 被引用文献数

- 1

1 0 0 0 ペルシア文学におけるカリーラとディムナ

- 著者

- 黒柳 恒男

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- オリエント (ISSN:00305219)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.12, no.1, pp.1-16,168, 1969

Pancatantra, famous collection of animal fables of Indian origin, was translated into Middle Persian by Burzoe in the sixth century, but this version was lost. In the eighth century, Ibn al-Muqaffa' translated the Middle Persian version into Arabic prose and named it "Kalila wa Dimna" after the names of two jackals in the text. This Arabic translation became the basis for subsequent Persian versions.<br>First of all, in the tenth century the famous poet of the Samanid court, Rudaki put the Arabic version into Persian verse form at Amir Nasr's request, but no more than several verses of this epic have survived.<br>Abu al-Ma'ali Nasr Allah, probably a native of Shiraz, translated the Arabic version into Persian prose about 1144, which was dedicated to Bahram-Shah of Ghazna. This version was made in such an elegant style that it had effect on many later Persian works, such as "Akhlaq-i-Nasiri" and "Marzban-nameh".<br>About the end of the fifteenth century Husain Wa'iz Kashifi made by far the best known Persian version, entitled "Anwar-i-Suhaili", which was aimed at simplifying and popularising Nasr Allah's version. But his style was much more bombastic and florid, with many exaggerated expressions and considerably expanded parts.<br>This bombastic version became simplified in India and Abu al-Fadl, a famous historian and minister under Akbar, compiled a book, entitled "'Iyar-i-Danish", which was derived from Kashifi's version.

- 著者

- 永田 雄三

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- オリエント (ISSN:00305219)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.12, no.3, pp.149-168,228, 1969

Among the principal subjects of interest in 18th-19th century Ottoman history is the political influence exerted on the reform policies of the central government by the local notables known as A'yân and Derebeyi.<br>While Mahmud II came to the throne, they, the local notables, at that time had divided and ruled even Anatolia and the Balkan area, vital parts of the empire.<br>So this time I have studied their political activities after the Russo-Turkish war of 1768-1774, with stress on the "Nizâm-i Cedîd" of Selim III and on the "Sened-i Ittifak" of 1808, and then referred to the policy of Mahmud II for subjugation of the local notables.

1 0 0 0 Irshad al-Zira'aの背景

- 著者

- 清水 宏祐

- 出版者

- The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan

- 雑誌

- オリエント (ISSN:00305219)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.27, no.1, pp.20-38, 1984

Irshad al-Zira'a "The Guide of Agriculture" was written by Qasim b. Yusuf Abu Nasri Harawi in 921/1515. It is supposed to have been prepared during the era of the Timurids. It is a mine of agricultural information. Its contents are as follows;<br>Selection of soil<br>Selection of time for cultivating<br>Cereals and manure<br>Grapes and vines<br>Vegetables<br>Trees and flowers<br>Care for trees and estimation of crops<br>Gardening<br>The sources of its information are considered as follows;<br>The knowledge of well experienced farmers<br>Greco-Islamic Science; Theory of Garenos and Plato<br>Books of Agriculture in Arabic and other languages<br>The opinion of 'ulama' and court officials<br>The most important is one from farmers. Judging from the names of varieties of grapes, wheats, barleys, and other crops, the geographical background of Irshad al-Zira'a is confirmed to be the world around Herat, namely the eastern part of Iran and the western part of Central Asia.