- 著者

- 久保 明教

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 文化人類学 (ISSN:13490648)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.71, no.4, pp.518-539, 2007-03-31 (Released:2017-08-28)

1999年に販売が開始されたエンターテインメント・ロボット「アイボ」は、生活空間において人々の間近で動作する初めてのロボットとして多くの注目を浴びた。本稿では、アイボの開発と受容の過程を横断的に検討し、テクノロジーにおける科学的側面と文化的側面がいかなる関係を取り結ぶかについて考察する。科学およびテクノロジーを社会的ないし文化的事象として捉える研究は近年盛んになされてきたが、その多次元的な性質ゆえにテクノロジーを包括的に考察することには困難が伴う。本稿では、アイボという技術的人工物が科学的知識、工学的製作、日常的実践等の接点となっていることに注目し、異なる領域に属する諸要素が接続される様々な局面を分析することで、境界横断的なテクノロジーの動態を捉えることを試みる。そこで明らかになるのは、開発と受容の過程において、科学的要素と文化的要素が組み合わされる中でアイボの有様が方向づけられていったことである。開発過程においては、人工知能研究およびロボット工学上の成果である設計手法を基盤にしながらも、ロボットをめぐる人々の想像力に基づいた語りを工学的装置へと翻訳することによってアイボがデザインされていった。一方、受容過程においては、アイボ・オーナーの生活する空間に特有の日常的な事物の有様とアイボの機能システムの作動が結びつくなかで、アイボの動作が様々な形で解釈されるようになり、開発者の想定を超える意味をアイボは獲得していった。筆者は、開発者による工学的デザインとアイボ・オーナーによる解釈が科学的要素と文化的要素を組み合わせることで妥当性を生み出す営為であったと分析した上で、実在と意味を媒介するテクノロジーの働きにおいて科学と文化の相互作用が捉えられることを示した。

7 0 0 0 OA 公的であり私的:ファン研究炎上の分析

- 著者

- 大澤 博隆 江間 有沙 西條 玲奈 久保 明教 神崎 宣次 久木田 水生 市瀬 龍太郎 服部 宏充 秋谷 直矩 大谷 卓史

- 出版者

- 人工知能学会

- 雑誌

- 2018年度人工知能学会全国大会(第32回)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 2018-04-12

オンラインサービスでは、ユーザーのコミュニケーション活動とコンテンツが公開される。 このオンライン情報は、ユーザー生成コンテンツの作成サイクルを加速するのに貢献する。 さらにこれらのサービスは、研究者がオンラインテキストを、社会活動の調査研究とも呼ばれる、人間活動を容易に分析するための公的な資源として利用することを可能にする。 しかし特に創造に関わる分野では、コンテンツが公開されている場合においても、プライバシーに関する論争の的になる問題が存在することを認識する必要がある。 本研究では、オンラインファンフィクション小説における性的表現の抽出とフィルタリングを試みた研究が起こした炎上事件のケースを通し、オンライン研究のための新しいガイドラインを作成しようと試みる。 本研究では法と倫理を含む工学と人文学の両方の分野の研究者が、それぞれの専門分野に応じて倫理的、法的、社会的問題を抽出した。

5 0 0 0 OA 対称性人類学からみる現代スポーツの主体

- 著者

- 久保 明教

- 出版者

- 日本スポーツ社会学会

- 雑誌

- スポーツ社会学研究 (ISSN:09192751)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.23, no.1, pp.19-33, 2015-03-30 (Released:2016-06-03)

- 参考文献数

- 4

本稿は、将棋電王戦における棋士とソフトの対局をめぐる事例分析に基づいて、現代スポーツに広く見られる、人間と非人間的なテクノロジーが結びついた主体の有様を探究するものである。 モバイル端末で体調管理を行うスポーツ愛好家から科学的トレーニングによって心身を鍛え上げるトップアスリートにいたるまで、現代のスポーツには人間的存在と非人間的存在が結びついたハイブリッドな行為体が遍在している。だが、こうした人間と非人間のハイブリッドはしばしば一方が他方に従属する形で理解され、「スポーツは人間がするものだ」という命題が維持されてきた。 本稿では、まず、ブルーノ・ラトゥールが提唱した「対称性人類学」のアプローチを参照しながら、スポーツに対するテクノロジーのあからさまな浸透が一般化した現代において、なぜ人間中心主義的なスポーツ観が維持されているのかを検討する。そこで見いだされるのは、科学技術によって客体化される自己とこうした科学的な客体としての自己を観察し制御する主体としての自己の明確な区別に基づいて前者を後者に従属させる再帰的な主体のあり方である。こうした「モニタリングする主体」の形象によって、ハイブリッドは覆い隠され、人間中心主義的なスポーツ観が維持・再生されてきたと考えられる。 これに対して、将棋電王戦をめぐる事例分析においては、棋士も将棋ソフトも共に人間的な要素と非人間的な要素が混ざり合ったハイブリッドな存在であること、電王戦の対局において、両者の「モニタリングする主体」としての有様がしばしば機能不全に陥っていったことに注目する。棋士とソフトのふるまいが観測可能な範囲の限界を超えて様々な人間的/非人間的要素と流動的な関係をとり結んでいく過程を検討した上で、最終的に、異種混交的なネットワークへと自らを託していく主体の有様において現代スポーツに遍在するハイブリッドな行為体を捉えうることを示す。

- 著者

- 久保 明教

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 文化人類学 (ISSN:13490648)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.71, no.4, pp.518-539, 2007-03-31

- 被引用文献数

- 1

1999年に販売が開始されたエンターテインメント・ロボット「アイボ」は、生活空間において人々の間近で動作する初めてのロボットとして多くの注目を浴びた。本稿では、アイボの開発と受容の過程を横断的に検討し、テクノロジーにおける科学的側面と文化的側面がいかなる関係を取り結ぶかについて考察する。科学およびテクノロジーを社会的ないし文化的事象として捉える研究は近年盛んになされてきたが、その多次元的な性質ゆえにテクノロジーを包括的に考察することには困難が伴う。本稿では、アイボという技術的人工物が科学的知識、工学的製作、日常的実践等の接点となっていることに注目し、異なる領域に属する諸要素が接続される様々な局面を分析することで、境界横断的なテクノロジーの動態を捉えることを試みる。そこで明らかになるのは、開発と受容の過程において、科学的要素と文化的要素が組み合わされる中でアイボの有様が方向づけられていったことである。開発過程においては、人工知能研究およびロボット工学上の成果である設計手法を基盤にしながらも、ロボットをめぐる人々の想像力に基づいた語りを工学的装置へと翻訳することによってアイボがデザインされていった。一方、受容過程においては、アイボ・オーナーの生活する空間に特有の日常的な事物の有様とアイボの機能システムの作動が結びつくなかで、アイボの動作が様々な形で解釈されるようになり、開発者の想定を超える意味をアイボは獲得していった。筆者は、開発者による工学的デザインとアイボ・オーナーによる解釈が科学的要素と文化的要素を組み合わせることで妥当性を生み出す営為であったと分析した上で、実在と意味を媒介するテクノロジーの働きにおいて科学と文化の相互作用が捉えられることを示した。

2 0 0 0 OA 公的であり私的:ファン研究炎上の分析

- 著者

- 大澤 博隆 江間 有沙 西條 玲奈 久保 明教 神崎 宣次 久木田 水生 市瀬 龍太郎 服部 宏充 秋谷 直矩 大谷 卓史

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人工知能学会

- 雑誌

- 人工知能学会全国大会論文集 第32回全国大会(2018)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- pp.3H2OS25b04, 2018 (Released:2018-07-30)

オンラインサービスでは、ユーザーのコミュニケーション活動とコンテンツが公開される。 このオンライン情報は、ユーザー生成コンテンツの作成サイクルを加速するのに貢献する。 さらにこれらのサービスは、研究者がオンラインテキストを、社会活動の調査研究とも呼ばれる、人間活動を容易に分析するための公的な資源として利用することを可能にする。 しかし特に創造に関わる分野では、コンテンツが公開されている場合においても、プライバシーに関する論争の的になる問題が存在することを認識する必要がある。 本研究では、オンラインファンフィクション小説における性的表現の抽出とフィルタリングを試みた研究が起こした炎上事件のケースを通し、オンライン研究のための新しいガイドラインを作成しようと試みる。 本研究では法と倫理を含む工学と人文学の両方の分野の研究者が、それぞれの専門分野に応じて倫理的、法的、社会的問題を抽出した。

- 著者

- 久保 明教

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 文化人類学 (ISSN:13490648)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.76, no.4, pp.497-500, 2012-03-31 (Released:2017-04-17)

- 著者

- 久保 明教

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 文化人類学 (ISSN:13490648)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.77, no.3, pp.456-468, 2013-01-31

Recently, it has become increasingly difficult to employ "culture" as a comprehensive analytical concept in anthropology. Nevertheless, in the practices of people researched by anthropologists, culture has recently taken on increasing importance as a vital tool to categorize human groups and manage their relations, owing to the ongoing process of globalization. Because of that, the Japanese anthropologist Shoichiro Takezawa has insisted that we must maintain the academic concept of "culture." However, the increasing practical importance of culture does not necessarily connote its importance as an analytical concept. Rather, we need to investigate how the concept works in people's practices today, and whether culture as an academic concept works in their analysis. Also, if the concept of "culture" hardly ever works, we must explore a way to demolish it as a concept and reconstruct analytical methodology. In this paper, I investigate the practices of IT workers in Bangalore, South India, in order to examine how culture is practically utilized there, as well as to try to understand why the academic concept of culture does not work well in analyzing their practices. I also examine the kind of framework required to describe them appropriately. In Chapter 2, I point out that in the Indian IT industry, a vital element for economic success has been identified as the understanding and adoption of foreign (mainly Western) cultures in order to communicate more smoothly with foreign clients, co-workers and customers in the global and virtual workplaces that make up informational networks. In Chapter 3, I examine two ways used to explain the practices of Indian IT workers engaged in managing cultural differences: the narratives of "cross-cultural management" and "sanskritization." Then, I show how the practical concept of culture utilized in these narratives has dual qualities ("something to control and invisible" and "something controlled and visualized"), and demonstrate that the analytical concept of culture hardly ever works for analyzing existing situations in which the practical concept of culture is employed, because it also implicitly contains those dual qualities. In Chapter 4, I examine an event encountered during my field research in Bangalore to suggest that the daily practices of IT workers deeply depend on a heterogeneous "actor network" composed of human/ nonhuman entities from different regions, which cannot be sufficiently comprehended by employing the practical/analytical concept of culture. In Chapter 5, I try to configure an analytical framework sufficient to describe their practices appropriately, connecting the relational ontology proposed by the actor-network theory to a vital idea of anthropology, namely, "their perspective." Referring to Donna Haraway and Marilyn Strathern, I insist that the concept of "their perspective" is not an (inter) subjective viewpoint, but the effect of a recursive movement of the actor network to visualize itself. Finally, I suggest that Indian IT workers are penetrated by different ways of organizing and visualizing the actor network, which are equivalent to four spatialities proposed by the discussion of ANT topology, and that their perspective is being generated and transformed through mutual interferences among them.

本研究は、情報処理機械(コンピュータ)を基盤とする先端テクノロジー、とりわけ現代日本のロボット・テクノロジー(RT)の発展において文化的知識が果たす役割を解明することを目的とする。本年度は、以下の三つの側面に焦点を絞り、研究の基盤となる成果を得た。第一に、研究の方法論の精緻化のため理論的研究を行った。テクノロジーと社会・文化の相互作用を分析する研究手法である「Actor Network Theory(ANT)」と文化人類学的研究を接合する方法論の確立を主題として研究会発表を行った(発表題目「マテリアリティの記号論」、東京外国語大学アジア・アフリカ研究所「『もの』の人類学的研究」研究会、4月12日)。また、科学技術と文化の相互作用を解明する既存の研究潮流には欠けがちであった時間論的視座の組み込みを目指し、フィールドワークデータをもとに理論的展開を試みる研究発表を行った(発表題目「テクノロジーの時間」、技術社会文化研究会、12月16日)。第二に、ロボットをめぐる文化的言説と科学的知識の生成過程を対象として系譜学的および生権力論的な観点から研究を行い、その成果を学会・研究会にて発表した(発表題目「文化としてのロボット/科学としてのロボット」、日本記号学会、5月11日。発表題目「自己と/のテクノロジー:ロボット、労働、主体」、生権力研究会、大阪大学、9月25日)。第三に、本研究の成果をより包括的な観点から整理し展開するため、インド共和国においIT産業の勃興と文化的社会的要素の相互作用を分析するため、ベンガルール等の都市に短期滞在し、IT産業に従事する人々を対象にインタビュー調査を行った(2月12日~3月27日)。

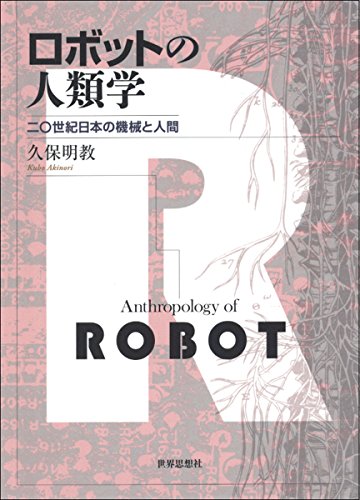

1 0 0 0 ロボットの人類学 : 二〇世紀日本の機械と人間

- 著者

- 久保 明教

- 出版者

- 社団法人人工知能学会

- 雑誌

- 人工知能 : 人工知能学会誌 : journal of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence (ISSN:21882266)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.29, no.5, pp.482-488, 2014-09

1 0 0 0 OA レヴィ=ストロース×スペルベルの象徴表現論 : コード化モデルを超えて

- 著者

- 久保 明教 クボ アキノリ Kubo Akinori

- 出版者

- 大阪大学人間科学部社会学・人間学・人類学研究室

- 雑誌

- 年報人間科学 (ISSN:02865149)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.29-1, pp.39-56, 2008