- 著者

- 藤本 健太朗

- 出版者

- 日本国際政治学会 ; 1957-

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.201, pp.66-81, 2020-09

- 著者

- 番定 賢治

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2020, no.198, pp.198_111-198_126, 2020

<p>This article focuses on activities of Japanese officials who worked for the Secretariat of the League of Nations (LN), and their influences in the Secretariat as a whole. Not only two Under Secretary-Generals (Inazo Nitobe, and Yotaro Sugimura) were appointed from Japan, but also many young officers (Ken Harada, Tetsuro Furugaki, and others) worked for the LN Secretariat. However, the number of Japanese officers in the LN Secretariat and the variation of the sections in which Japanese officers in the LN Secretariat engaged was evidently smaller than those of officers from any other permanent council member States. As for Japanese officers in the LN Secretariat, expertise in policy making is not so much important as ability to adapt themselves to Eurocentric environment of the LN Secretariat, and the main missions of Japanese officers in the LN Secretariat were liaison work between the LN Secretariat and Japanese government or Japanese press, and propagation of information about the work of the LN towards Japanese public. However, some Japanese officers were engaged in more various works, such as drafting communiques in some committees of the Assembly, and liaison work between the LN and other Asian nations. Moreover, during their temporary visits of Japan, Japanese officers in the LN secretariat went on lecture trips to promote understanding of the activities of the LN, and Nitobe's lecture trip from 1924 to 1925 led to the creation of Tokyo branch of the LN Secretariat Information Section, which enhanced propagation of specific information about the work of LN. When the Institute of Pacific Relations (IPR) invited the LN Secretariat to its conference, Nitobe insisted that this institute and Pan-Pacific movement would be helpful to support the activities of the LN, and Sugimura and other Japanese officers in the LN Secretariats repeatedly insisted the significance of IPR for the LN. In 1927, two officers of the LN Secretariat (One of them was Setsuichi Aoki, the head of Tokyo branch of the LN Secretariat) was sent to the second biannual conference of IPR. In 1929, when the third biannual conference of IPR was held at Kyoto, Sugimura himself attended the conference. However, at the time of this conference, Sugimura tried to invite the LN representative in the conference to Manchuria and Korea, which indicates Sugimura's intention to lead the LN Secretariat to support the political interest of his home country.</p>

1 0 0 0 OA 戦後初期台湾における脱植民地化の代行

- 著者

- 楊 子震

- 出版者

- JAPAN ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2010, no.162, pp.162_40-55, 2010-12-10 (Released:2012-10-20)

- 参考文献数

- 104

This paper focuses on Ryukyuans and Koreans living in Taiwan after the end of the Second World War, and by drawing a comparison of disparity in treatment between these two ethnic groups, examines the Chinese Nationalist government's seizure of Taiwan.The theme of this paper is “vicarious decolonization.” As a consequence, neither the ruling power (suzerain: Japan), nor the ruled (colony: Taiwan) were involved in the actual process of decolonization. For this reason the decolonization of Taiwan can be deemed to have been carried out vicariously.In this paper, I begin by discussing the Chinese Nationalist government's post-war relations with the Ryukyu Islands and the Korean Peninsula. Then, against the background of the collapse of the Japanese colonial empire and the Chinese Nationalist government's seizure of power, I compare the repatriation and conscription of the Ryukyuans and Koreans living in Taiwan by the Chinese Nationalist government by focusing the discussion on the drawing of boundaries among ethnic groups in Taiwan. Finally, I discuss the role played by the Chinese Nationalist government in Taiwan's post-war decolonization.Although the repatriation of the Ryukyuans and Koreans occurred slightly apart, there was little actual difference in the processes of repatriation. Soldiers and army personnel were repatriated at an early stage, followed by the repatriation of ordinary residents. The Chinese Nationalist government actively pursued the conscription of experts and engineers deemed useful for governing Taiwan.However, the conscripted experts and engineers were all outsiders, and the concept of conscription was nothing more than a temporary measure by the Chinese Nationalist government to secure its rule of Taiwan. The system of conscription conducted by the Chinese Nationalist government was a miniature copy of the pre-existing structure formerly adopted by Japan. Although there were some Ryukyuans amongst the experts and engineers working in the administration and research organizations, most positions were occupied by those born on the Japanese mainland. The fact that no Koreans can be found on the list of conscripts implies that Koreans were not included as part of the administrative side within the governing structure of the former colony of Taiwan.The Chinese Nationalist government's policy of repatriation and conscription of “Japanese people” reestablished borders among ethnic groups in Taiwan, and resulted in the vicarious decolonization and withdrawal of Taiwan from the Japanese colonial empire, while at the same time, through a continuation of existing occupation policies, was oriented toward maintaining the status quo.

1 0 0 0 シリアにおける政治変動:中東:1970年代の政治変動

- 著者

- 岡倉 徹志

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1983, no.73, pp.28-43,L8, 1983

The purpose of this paper is to present a brief account of the political changes in Syria since the Baa'th first came into power in 1963 and the development of inner-politics from the beginning period of the Baa'th regime to the present. It is also designed to offer an interpretation of these developments to help explain the kaleidoscopic character of the changing relationships among power-centers.<br>In particular, this paper attempts to elucidate the following points: Firstly, in a major intra-party split that took place in February 1966, the moderate wing of the Baa'th party was purged by radicals; this political coup signaled the party's further turn to the Left in policy. These changes only further alienated conservative and pious Islamic opinion. However, the regime's mounting clashes with the West and Israel have temporarily disoriented Muslim opinion.<br>Secondly, after General Hafiz al Asad's rise to power in 1971, the question arises as to how he managed to revise Syria's domestic and foreign policies. By late 1976, however, the regime's policies were faltering and domestic grievances were accumulating; relations between the Baa'th and urban centers of opposition again began to sour, a disaffection that gradually built up into the anti-regime explosions of 1970-80.<br>The regime's intervention in Lebanon—in paticular, its drive against the Palestinians and the Sunni Left—required it to suppress domestic opposition, thus weakening its own support base, and antagonizing segments of Sunni opinion, which viewed it as an Alawite suppression of Sunnis in favor of Christians. Most dangerous of all, the intervention seriously exacerbated sectarian cleavages in the army. By the late 1970s, the regime's foreign policy increasingly appeared to have reached a dead end.<br>Finally, the political Islam, the main alternative. to the Baa'th, is now trying to undermine the regime led by the Alawites. If a realignment of political forces, pitting the whole Sunni community on the basis of sectarian solidarity, in alliance with all other disaffected elements, against the numerically much inferior Alawites entrenched in the regime can be attained, the Syrian political scene will change completely its impact affecting the politics of the Fertile Crescent. But this would require breaking the cross-sectarian coalition at the center of the Baa'th state; destroying military discipline and party solidarity; and detaching the peasant, worker, and employee elements at the Baa'th base.

- 著者

- 溝口 修平

- 出版者

- 日本国際政治学会 ; 1957-

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.201, pp.114-129, 2020-09

- 著者

- 宇山 智彦

- 出版者

- 日本国際政治学会 ; 1957-

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.201, pp.98-113, 2020-09

- 著者

- 河本 和子

- 出版者

- 日本国際政治学会 ; 1957-

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.201, pp.82-97, 2020-09

1 0 0 0 ソヴェト・ロシアの対イラン外交の始まり (ソ連研究の新たな地平)

- 著者

- 李 優大

- 出版者

- 日本国際政治学会 ; 1957-

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.201, pp.49-65, 2020-09

- 著者

- 地田 徹朗

- 出版者

- 日本国際政治学会 ; 1957-

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.201, pp.33-48, 2020-09

- 著者

- 松井 康浩

- 出版者

- 日本国際政治学会 ; 1957-

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.201, pp.1-16, 2020-09

- 著者

- 板橋 拓己

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2020, no.200, pp.200_67-200_83, 2020

<p>With respect to the international negotiations on the German unification in 1989/1990, not only the massive publication of memoirs by contemporaries, but also the release of historical materials by governments concerned has advanced the elucidation of the event. Existing studies, however, tended to characterize the German unification on October 3, 1990 as "goal" and to assess who contributed to it. On the other hand, more recent studies have shifted the research interest from the "happy end narrative". In other words, they came to regard German unification not as "goal" or "end" but as "start" or "formative phase" of the post-Cold War European international order.</p><p>While sharing the view that the German unification process is a period of the formation of the post-Cold War European international order with the latest research, this paper focuses on the issue of NATO (non-)enlargement. Using newly available diplomatic sources, the author tries to reevaluate the role of Hans-Dietrich Genscher, foreign minister of the FRG. What is clear from this approach is the differences of visions within the West German government concerning how to end the Cold War and what kind of new international order should be created, and the impact of these differences on actual international politics.</p><p>As shown in this paper, it can be said that after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Genscher had consistently envisaged "the ending the Cold War by emphasizing reconciliation with the Soviet Union." The Bush administration, on the other hand, placed top priority on the survival of NATO. After the Camp David talks in late February, the Bush administration and Helmut Kohl, Chancellor of the FRG, began to seek "the ending the Cold War based on the preeminence of the United States or NATO."</p><p>Kohl, who strived for the swift reunification of Germany, put priority on cooperation with the United States on security issues. Nevertheless, Genscher continued to stick to his vision. Due to Kohl's rebuke and the Bush administration's pressure, he no longer spoke of the NATO's non-expansion to the east after April 4, 1990, but repeated arguments for strengthening the CSCE and changing the nature of NATO. Ironically, it was Genscher's idea that was subsequently effective in convincing the Soviet Union of a unified Germany's full membership in NATO. Genscher contributed to the end of the Cold War in terms of the "victory of the West" by advocating his vision of the end of the Cold War as a "reconciliation with the East" even after it lost its reality.</p>

1 0 0 0 フランスの国際連盟政策と「ウィルソン主義」、一九一九―一九二四年

- 著者

- 細川 真由

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2020, no.198, pp.198_64-198_79, 2020

<p>The previous studies have not considered Wilsonianism in relation to French diplomacy, but after the World War I, France played a key role in the League of Nations, from which its advocate, the United States of America, has been absent. Therefore this paper focuses French policies for the League of Nations in order to reexamine "Wilsonianism." From 1919 to 1924, French leaders at first had bad feelings toward the League of Nations or the "New Diplomacy," but they gradually have accepted such conceptions.</p><p>First, this paper examines French leaders' attitude for Woodrow Wilson or his idea for peace. In the Paris Peace Conference (1919), French prime minister, Georges Clemenceau, was suspicious of Wilson and his idea, and required the military alliance with the United Kingdom and the United States. And also, he persisted in the military occupation of the Rhineland. On the other hand, at the commission drafting the Covenant of the League of Nations, Léon Bourgeois advocated establishing an international force. However, their proposals were discarded, because the United States had rejected the peace treaty and the Covenant.</p><p>Second, this paper considers French attitude for the League of Nations from 1920 to 1923. During this period, France has looked for a more powerful mechanism of the national security, but each of French attempt for the security was deadlocked. However, in 1923, the Draft Treaty of Mutual Assistance (Projet de traité de garantie mutuelle) was submitted to the Assembly of the League of Nations. This draft has tried to enforce disarmament and collective security as one, but it broke down because of the British opposition.</p><p>Finally, this paper focuses the Protocol for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes (Protocole pour le réglement pacifique des différends internationaux) in 1924. This protocol was strongly supported by the new French prime minister Édouard Herriot. He looked for the alliance with the United Kingdom at first, but British prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald, rejected his offer. Therefore, Herriot sought to put his plan into practice at the League of Nations. However, after all, this protocol broke down, too.</p><p>As stated above, France has sought to strengthen the collective security, either at the League of Nations or at the bilateral level. From 1919 to 1924, each of French attempt for the security turned out a failure. However, in this period, France gradually accepted the principle of "New Diplomacy." And in this background, there is the unstable domestic situation, such as the fall of franc or the frequent changes of government. Under the circumstances, for France, the value of the League of Nations has steadily been raised.</p>

- 著者

- 斎藤 治子

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1988, no.89, pp.7-23,L6, 1988

The study of Greek anti-fascist movements during the Second World War has developed since the 1970s. The Colonels' dictatorship dissolved in 1974 and the Greek Communist Party (KKE), outlawed by the dictatorship, was then legalised. Books and articles written by KKE members who had took part in the anti-fascist movement have been published.<br>The anti-fascist movement in Greece had two aims; national liberation and democratization. In 1936 Prime Minister Metaxas secured the assent of King George II to the suspension of the democratic articles in the Constitution and parliament was adjourned without delay. Metaxas outlawed the KKE, introduced censorship and dealt badly with anti-monarchists. He organized the National Youth Organization on totalitarian lines. This quasi-fascism, however, was not popular among the Greeks because of their traditional individualism. Metaxas, who monopolised seven portfolios in the government, had a less massive party than Hitler had.<br>On 28 October 1940 the Italian ambassador handed to Metaxas the ultimatum claiming some important areas in Greek territory, but the latter said “No (0 χ ι in Greek)”. He appealed to the people for fierce resistance against the Italian forces invading across the Albanian-Greek frontier. His rejection of the ultimatum and the appeal set fire to the patriotism of the Greeks. For the first time he succeeded in the unification of the nation. Rank and file, young and old, who opposed the Metaxas' dictatorship (4 August Regime), in the front and the rear fought against the invaders. Soon they liberated the occupied territory, and counter-attacked across the border and occupied the Greek-inhabited southern area in Albania which Greek nationalists had long aspired to. The victory has temporarily identified the people with the dictatorship.<br>In April 1941 the Germans attacked Greece assisting the Italians and in two weeks occupied Athens. King and the government (Metaxas had died in January but “4 August Regime” succeeded) withdrew to Crete, which the Germans occupied in May, and then to Egypt. They established a government-in-exile in London at first, then in Cairo. In the Axis-occupied Greece a puppet government was established, headed by the ex-commander of the Greek Army.<br>Resistance groups were formed during the occupation. They were led by outlawed KKE members or democratic civilians or republicans. The general secretary of KKE had been imprisoned and the party had been divided. The underground and imprisoned cadres decided to unify the party and to organize the nation-wide resistance movement in order to struggle for national liberation and independence. The struggle was also aimed at the abolition of the “4 August Regime”.<br>In September 1941 the National Liberation Front (EAM) was founded on the initiative of KKE. EAM consisting of four political parties that declared their common struggle against the occupants. Its slogans were national liberation and people's democracy (laocratia).<br>The main object of the article is the analysis of the interrelation between national liberation and social evolution in Greece.

- 著者

- 東郷 育子

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2000, no.125, pp.115-130,L15, 2000

When grave human misery such as genocide is committed in a country, should international society intervene regardless of sovereignty? To intervene in the domestic affairs of another nation has been illegal under the regime of traditional International Law. Recently, however, if a certain government seriously violates human rights of his citizens, or rulers clearly do not have the ability to govern, and the media reports of human catastrophes which arouse public opinion around the world, international society has enough and justifiable reasons to intervene in the concerned state.<br>The Gulf War was an important turning point in several respects that brought reform in humanitarian intervention of the Post-Cold War era. First, international society, especially the major powers, showed they could cooperate in taking military actions under the leadership of the United Nations. Second, the bases of permitting humanitarian intervention matured and the media performed an important function in this trend. Third, in order to realize intervention and persuade public opinion, various efficiencies of intervention, such as “zero casualty” and air raids, as a major strategy, have been important.<br>Success in the Gulf War introduced a more positive concept of humanitarian intervention. Namely, humanitarian intervention does not solely point to military intervention as a means of conflict resolution, but also includes broader methods such as humanitarian actions to prevent conflict itself and peace-building efforts after conflicts.<br>There still remain some questions regarding humanitarian intervention. For example, how should we set the standards to intervene? How can the operators maintain humanitarian neutrality and justice? What is the goal, and to what extent should intervention go? Only after we overcome these questions will the potential to build accountability for humanitarian intervention develop.<br>Humanitarian intervention in the 21st century must operate under the recognition of human conscience and social justice. At the same time it must pursue not self-interest but universal interest. In the medium to long term, humanitarian intervention must eliminate structural conditions and bases of human rights violation. In the long run, it must contribute to peace building and help the concerned state become independent as a modernized and democratized society. All actors who intervene-not only nations, but also regional organizations, international organizations, NGOs, and citizens-should be responsible for this final goal. The question of how we should undertake humanitarian intervention in this global society is indeed to understand how these actors intervene and work functionally in each role to assist the concerned state suffering human misery.

- 著者

- 千知岩 正継

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2013, no.171, pp.171_114-171_128, 2013

In recent years, some IR theorists have begun to depart from the assumption of anarchy and to shed light on certain forms of inter-state hierarchy. Stimulated by those new studies, this article engages in a discussion on the legitimacy of a global authority which is expected to preside over 'Responsibility to Protect (R2P)' norms.<br>The first part of this paper clarifies the global authority governing R2P norms, and explains its critical importance. Drawing upon the concept of "right authority" in just war traditions, it is argued that a global authority in relation to R2P is supposed to decide whether certain states fail to fulfil their responsibility to protect, and if necessary, to take responsibility for authorizing military interventions for human protection. This will inevitably determine the nature of global order.<br>The following two sections examine both the United Nations Security Council and a proposed concept of "Concert of Democracies" as possible candidates to be the global authority. As a universally agreed legal authority, the Council is entrusted with the fulfilling of R2P principles, and in fact many commentators saw the Council decision in the case of Libyan civil war as its first successful implementation of R2P. However, the Council has critical legitimacy deficits in terms of its selective function to the intractable question of "for whom should the Council be ultimately accountable and responsible?" As for the idea of "Concert of Democracies" it is a reflection of "liberal hierarchy" based on the solidarity of liberal democracies, and presented as a preferred alternative to the illegitimate and ineffective Council. On the contrary to optimistic expectations, it is demonstrated that its exclusive membership and misguided assessment of liberal democratic states behaviour will undermine this institution's legitimacy.<br>In conclusion I suggest two daunting challenges that the Security Council should overcome as the global authority responsible for putting R2P norms into practice. The first is to translate a plurality of values and interests of the Council members into the unity and effective decision making in times of humanitarian tragedies. The other challenge concerns the need for the Council to seek legitimation not only from member states but also from those people severely affected by the Council action or inaction. This might involve a transformation of the Council from globally acting authority into a kind of cosmopolitan authority based on the approval of "we the people" If this is the case, a new form of the Council authority will need further consideration.

1 0 0 0 OA ナイジェリアにおける「軍の中立性」と「法の支配」

- 著者

- 戸田 真紀子

- 出版者

- JAPAN ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2010, no.159, pp.159_27-40, 2010-02-25 (Released:2012-06-15)

- 参考文献数

- 44

Recently the scholars studying conflict theories or peace building in Africa have tended to neglect the historical perspective of Africa. Without knowing the history of traditional kingdoms and chiefdoms, including slave trade, colonialism, and neo-colonialism, we cannot accurately understand serious problems with which African people are now confronted.Coups d'etat are common in Africa. Nigeria in particular, an oil-rich African giant, has experienced the military rule for about twenty-nine years since its independence. Why did the Nigerian officers decide to seize the power? Why did they desire to keep the power for such a period of time? And, why don't they intend to withdraw from the political arena? To answer these questions, we should consider the impact of British rule in Nigeria.The Nigerian army was originally established to conquer the native kingdoms and chiefdoms under the policy of British colonization. British rulers sometimes undermined the “rule of law.” Later the Nigerian army became the tool for traditional rulers, who started to work for the British rule in order to suppress their own people. New rulers of independent Nigeria learned how to use the military to defend their vested interests during 1960 through 1966. Therefore, it is the negative legacy of British rule that civilian and military regimes had not maintained “law and order” to save the lives of Nigerian people. So many civilians, being involved in armed conflict between Nigerian army and rebellions, were killed by the army.Samuel Huntington showed two conditions to avoid military intervention. According to him, the civil-military relation may be destroyed if the governments would not be able to promote “economic development” and to maintain “law and order” and if civilian politicians would desire to use the military power for their own political ambitions.As to the “economic development,” approximately 80% of Nigerian people suffer from poverty, whereas the retired generals enjoy their political power as well as financial business with a plenty of money. As mentioned above, the aspect of “law and order” has been also neglected by the regimes. After independence, civilian regimes used the military for their political interests and led the army officials into the political arena.Therefore, as suggested by Huntington, military intervention may be caused in Nigeria again if the Fourth Republic would neglect the importance of promoting “economic development” and of maintaining “law and order.” The Fourth Republic also needs to keep the army out of politics and the politics out of the army to avoid military intervention. Actually it is difficult to meet these conditions, because the group of retired generals still has strong influence over political and economical arenas.

1 0 0 0 OA グローバル社会における政治と責任

- 著者

- 大芝 亮

- 出版者

- JAPAN ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2008, no.152, pp.168-176, 2008-03-15 (Released:2010-09-01)

- 参考文献数

- 31

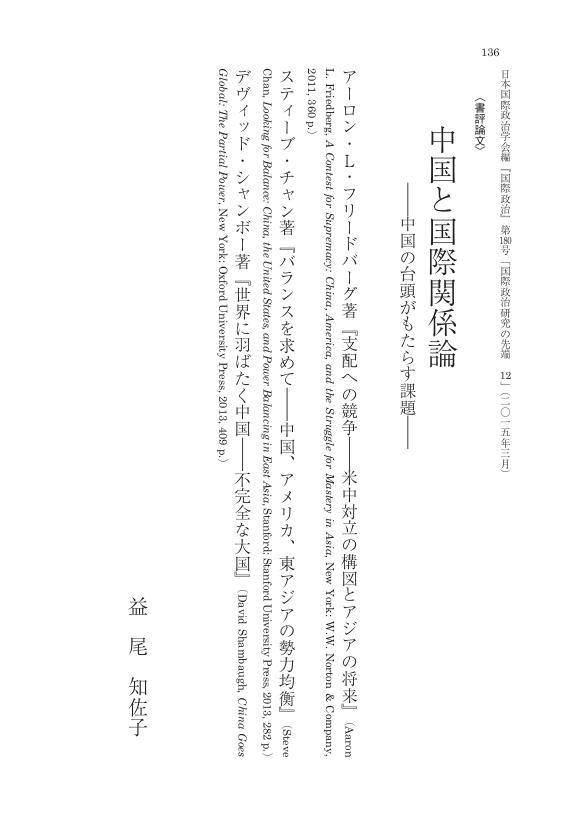

1 0 0 0 OA 中国と国際関係論 ―中国の台頭がもたらす課題―

- 著者

- 益尾 知佐子

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2015, no.180, pp.180_136-180_145, 2015-03-30 (Released:2016-05-12)

- 参考文献数

- 9

1 0 0 0 OA イスラエルの安全保障観

- 著者

- 木村 修三

- 出版者

- JAPAN ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1979, no.63, pp.55-68,L3, 1979-10-15 (Released:2010-09-01)

- 参考文献数

- 39

(1) Israel is not a militaristic state although she is a model of ‘nation-in- arms’ in the sense that military defense occupies the center of her people's life.(2) The reason why Israel is ‘nation-in-arms’ is due to the fact that she was surrounded by hostile countries which do not recognize her legitimacy as a state, and that she has actually fought four times with them in the past. In addition to this, holocaust analogy and ‘Masada complex’ which are latent in the psychology of Israelis, highten terror in their heart.(3) But, up to now, Israel has never faced the critical situation in which she could be actually annihilated. Rather, she has always won overwhelming victory in the past wars, with the only exception of the Yom Kippur War. At the same time, it is an undeniable fact that the terror of annihilation has been utilized for the justification of her intransigent policy.(4) Israel has tried to persuade the Arab states for their recognition of Israeli's legitimacy as a state, while totally rejecting the wish of Palestinians for the establishment of their independent state. After the end of Six-Day-War, Israel has made every efforts to secure her security on the basis of tei ritorialism by bringing out the conception of ‘defensible borders’.(5) If Israel wishes to secure the true security, it might be indispensable for her to recognize the Palestinians' legitimate rights of self-determination through peaceful settlement, in stead of insisting the conception of security on the basis of territorialism.

- 著者

- 立山 良司

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2005, no.141, pp.25-39,L7, 2005

Since autumn of 2000 the circle of violence has derailed the Israel-Palestinian peace process. In order to prevent the resurgence of violence both parties had tried to promote security cooperation and form an effective security regime between them, but failed to do so.<br>It is reported that since 1988 till 1998 thirty-eight formal peace accords were signed, and of them thirty-one failed to last more than three years. Various factors, such as security dilemma, existence of spoilers, and intervention by external parties, cripple the implementation of the peace accords, including the Oslo peace agreement. In addition, the asymmetrical relations between Israel and Palestinians have heavily affected the peace process and resulted in its failure.<br>One of the most salient asymmetrical relations is the difference in the nature of both parties. Israel is an independent sovereign state with very powerful armed forces, and has occupied The west Bank and the Gaza Strip. As such, Israel uses its armed forces under the name of invoking the right of self-defense, and has an almost excusive power to determine a future of the occupied territories. On the other hand, despite the establishment of their own self government, Palestinians are still under occupation and struggling for establishing an independent sovereign state. The asymmetrical future also results in a very wide gap between both parties' perceptions of peace. From Israeli viewpoint, a peace should bring an end of any form of violence and eliminate the threat of military and terrorist attacks. For Palestinians, a peace should realize both an end of occupation and an establishment of an independent Palestinian state. Furthermore over the peace process both parties, i. e. the Israeli Government and the Palestine Authority/PLO, have taken even conciliatory attitudes and policies toward spoilers in their own constituencies with the intention to broaden their power basis.<br>A number of proposals and suggestions for a military intervention by a third party have been made, but no international presence in the occupied territories has been materialized. Taking into consideration the asymmetrical characteristics between the two parities, however, an international presence could make valuable contributions to restoring a peace process in the following two aspects. First, an international presence could ease to a certain extent an asymmetrical feature of the relations and reduce the feeling of vulnerability on both sides. And by doing so, an international presence could narrow the gap of perceptions concerning peace. Second Israel and Palestine are no exception that political leaders manipulate security concerns to solidify their positions and extract additional resources from their society and consequently they create and intensify the security dilemma. The introduction of an international presence could decrease the possibility of this kind of manipulations.