1 0 0 0 OA 佐野安仁監修 加賀裕郎・隈元泰弘編集『現代教育学のフロンティア』

- 著者

- 土戸 敏彦

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.169-170, 2004-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 杉浦 宏編『現代デューイ思想の再評価』

- 著者

- 松浦 良充

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.171-172, 2004-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA フモリスト的覚醒的教師としてのキルケゴール 仮名著者ヨハンネス・クリマクスの語りから

- 著者

- 山内 清郎

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.90, pp.1-19, 2004-11-10 (Released:2010-01-22)

- 参考文献数

- 40

This paper explores an aspect of Søren Kierkegaard as a humoristic awakening teacher. In the theory of education, Kierkegaard has been well known as an existential thinker. The concepts of 'awakening' and 'subjective decision' are considered to be unique to Kierkegaard. A good deal of effort has been made to clarify the relation of educational theory and existential philosophy, a topic which is not ours here. Our concern is with the examination of the performative role that Kierkegaard intends to play in front of his audience.Kierkegaard describes himself as a humorist in his Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, whose author is Johannes Climacus (one of Kierkegaard's pseudonyms). The question here is if we have not often overlooked the fact that the text is written by a humorist. Have we paid due attention to the nuances and atmospheres of the narrative of Climacus? To begin with, we have to inquire into the meaning of “misunderstanding” which Kierkegaard thinks as one of his main themes all through his authorship. A great deal of misunderstanding in his age has made it necessary for Kierkegaard to adopt pseudonymous authorship and to communicate in an experimental form of a humorist.Then, a detailed analysis of Climacus' humoristic narrative illustrates four features of a humorist : (1) continually to join the conception of God together with something else and to bring out contradictions; (2) not to relate himself to God in religious passion; (3) to change himself into a jesting and yet profound transition area for all the transactions; (4) to renounce the concordance of joys that go with having an opinion and always to dance lightly.Lastly, it seems reasonable to suppose that Climacus' usage of “existence” is far from that of a conventional context of existential philosophy. This view on humoristic style of Climacus' narrative should throw new light on the relation between educational theory and Kierkegaard.

1 0 0 0 OA ルソーの宗教教育論に関する一考察 その指導法に焦点をあてて

- 著者

- 田中 マリア

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.90, pp.20-37, 2004-11-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

- 参考文献数

- 35

The paper examines the meaning and significance of J. J. Rousseau's method of religious education. Although Rousseau takes up religious education in “Émile”, he doesn't argue what kind of methods should be used. He only inserts the famous story of “Profession de foi du vicaire Savoyard” in book 4 of “Émile”. The question as to why Rousseau's “Émile” remains silent on the concrete method of religious education seems not to have been properly answered so far.This paper throws light upon this question through a reexamination of Rousseau's reminiscence, “Profession de foi du vicaire Savoyard”.Through the examination the following points have been clarified : 1. The reason why the inserted story is very long comes from the fact that Rousseau thinks an inner piety very important. It was necessary for him to show what inner piety is and how one comes to obtain it. So he tried to show the whole process of religious education using many pages.2. The reason why the whole process is narrated by this one priest derives from the fact that Rousseau thinks it important to put the piety into practice. He didn't try to adopt arguments on religion which would not be realized in practice.3. The fact that he adopted the style of story telling shows that he aimed at leading Emile to acquire a reason which is consistent with the mind and deal of the gospels. A story or a narrative, which utilizes both phonetic and symbolic languages, was a useful style of expression, on which Rousseau placed a high value as a measure to communicate one's thoughts and sentiments.

- 著者

- 平井 悠介

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.90, pp.38-55, 2004-11-10 (Released:2010-01-22)

- 参考文献数

- 43

The purpose of this paper is to clarify the trends of the liberal arguments that aim to solve the conflict between parents and state over the educational authority, and to consider the significance of the theory of deliberative democracy. In the liberal democratic society, parents are assumed to have a natural right to raise their children in their own way : Children should be educated by their parents privately. Yet children are simultaneously the objects of public education, because they should be citizens in future. These two aspects of child-education make a conflict between parent and state (ex. Mozert v. Hawkins Country Board of Education). Thus we have to consider the way to balance the educational authorities between parents and state. For this purpose, this paper considers the theories of three contemporary political philosophers, William, A. Galston, Stephen Macedo and Amy Gutmann.First, I will analyze their arguments concerning the case of Mozert, and classify their political stances. Macedo and Gutmann regarded the mandatory civic education as important while Galston thought there was the danger that it violated the individual liberty. However, Macedo and Gutmann also had different claims about the contents of civic education. Second, I will consider the criticisms of Gutmann's argument by Galston and Macedo. They claimed that her argument based on autonomy could not be justified. But, in my view, they overlooked the egalitarian feature in her argument. Finally, I will conclude that Gutmann's theory of deliberative democracy has been more sensitive to the religious diversity than other theories, and that she has succeeded in solving the conflict between parents and state.

1 0 0 0 OA 何のための教育哲学研究だったのか

- 著者

- 増渕 幸男

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.126-137, 2004-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

- 参考文献数

- 8

唐突と思われるかも知れないが、現在の心境として田辺元の『懺悔道としての哲学』を無性に読みたくなり手にした。田辺が論ずる自力と他力の弁証法に引き込まれつつ、やがて理性批判としての哲学の避けがたい運命から帰結する「絶対批判」という言葉に圧倒された。その後、田辺がハイデガーの下で学び、日本の研究者にありがちな西洋の哲学 (者) への盲目的追従ではなくて、徹頭徹尾ハイデガー哲学との対決に心血を注いだことがわかってきた。また、田辺ほど西洋的理性の論理や体系に抵抗した哲学者も少ないであろうが、その評価については西谷啓治の「田辺哲学について」 (著作集第九巻) を読んでいて、見通しがよくなった。そのさい衝撃的であったのは、「理性の立場といふものが根抵のところで破綻に陥る」ところには、「人間の存在にとって種的な基体と呼ばれ得るようなもの、具体的にいへば民族とか国家」の問題が出てくるという「種の論理」の指摘である。さらに、西谷の論稿「田辺先生最晩年の思想」には、田辺の『哲学と詩と宗教』が取り上げられ、田辺がヘルダーリン批判を展開する中で、生の哲学に基づく民族主義的傾向が明らかにされていて、それがハイデガーの重視する民族的土着性への批判を意図していたと教えている。これはドイツロマン主義がナチズムに結びついていったものであるが、ドイツ民族の最深部に隠れていた精神的暗部を、すでに田辺がハイデガーの思想をとおして見抜いていたことでもある。このような文章からエッセイを書き始めたのは、それなりの理由があってのことである。これまで自分が学んできた教育哲学研究の姿勢には、右のようなドイツ哲学との批判的対決がなかったこと、そしてそれ以上に、ドイツ哲学を可能にしている民族精神を問題視してこなかったことへの猛省と自戒の気持ちが、近年頓に強くなっていたからである。はっきり言えば、これまでの自分の研究姿勢は誤っていたのではないかという疑問が出てきたからである。そのきっかけとなったことは、国の内外を問わず、現実世界の混迷状態に対して、自分が教育学研究者としての責任を遂行してきたのかどうかの疑問を抱いたことにある。もちろん、この種の素朴な疑問は誰もが感じていることであろうし、敢えて指摘するまでもないかも知れない。ところが、この二年間に国際社会はテロと戦争・民族紛争を過激なまでにエスカレートさせる方向に進んでいることを真摯に受け止めると、教育現場で人類の平和や共生の大切さを唱えることの無力さが伝わってくる。そこで人類の歴史の教訓とは何か、それを生かすための教育のあり方とは何か、という現実的課題を突きつけられたと言えるであろう。つまり、教育理論は現実が抱えている問題にどこまで踏み込めるかという考察なしには、理論を構想することの虚しさに囚われざるをえないのである。グローバル化、国際的共生社会といったキーワードが飛び交う一方で、テロ、ジハード、拉致問題と失業問題といった言葉が不協和音を奏でている現実がある。こうした現実を直視した時に求められる教育の理論とは、一体どのようなものなのだろうか。右の疑問と向き合ってみて、「ヤスパースとアーレント-ユダヤ人問題にみる公と私の同化問題-」 (「コムニカチオン」第十一号日本ヤスパース協会平・十二年) 「国際化時代の教育の課題-精神的公共性をめぐって-」 (「ソフィア」第五〇巻、第一号平・十三年) 「教育問題としてのグローバリゼーション」 (「ソフィア」第五一巻、第一号平・十四年) を書く中で、現代が一世紀前と同じような世界史の歩みと重なってくる面があることに気づかされたのである。そのことを確認するために取り組んだ一つが、ユダヤ人を地球上から抹殺しようと企てて、人類的罪を犯したナチスのユダヤ人問題である。そこで、この二年間に収集してきた資料を整理してまとめたのが、最近著の『ナチズムと教育-ナチス教育政策の「原風景」-』 (東信堂平・十六年) である。ところが、その取り組みの過程で、先述した田辺元の唱える何かと通底するものを漠然となりとも感じたばかりでなく、これまで自分が取り組んできたドイツ教育学研究のあり方は間違っていたのではないか、という疑問にぶつかったのである。そのことがまた、ナチスの陰謀を阻止できなかったドイツ教育学 (者) に対する疑問へとつながっていった。そうした一連の流れを吐露することになる本エッセイは、これまでの教育哲学研究に対する懺悔道としてのモノローグである。

1 0 0 0 OA 教育哲学を考える

- 著者

- 生田 久美子

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.138-139, 2004-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 松下良平著『知ることの力-心情主義の道徳教育を超えて』

- 著者

- 齋藤 勉

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.140-144, 2004-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 福田 弘著『人間性尊重教育の思想と実践-ペスタロッチ研究序説』

- 著者

- 森川 直

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.145-151, 2004-05-10 (Released:2010-01-22)

わが国のペスタロッチ研究史に新たな一ページが加えられた。本書は、学位論文「ペスタロッチ教育思想における宗教的基礎-その形成と展開」 (一九九九年十一月筑波大学) をもとに編まれたもので、著者の積年の研究の集大成とみなされるものである。「まえがき」で、著者は本書について次のように述べている。「本書は、従来もっぱら教育の近代化の先駆者として位置づけられてきたペスタロッチの教育思想と実践を改めて問い直し、ペスタロッチの教育思想と実践の根底には、一般的には『非合理的』、『非近代的』であると批判されがちであった宗教観が、それもきわめて根源的 (ラジカル) な、敬虔主義的で実践的な深い宗教観が、厳然と存在していることをまず論じている。そして、この宗教的基盤こそが、かれの人間観とそれにもとづく人間性尊重に徹する実践的教育思想を支えているということ、また、それゆえにこそ、かれの教育思想は、近代がもたらしたさまざまな負の遺産を克服し、あらたに人類に希望と勇気を与えうる教育を創造する基礎力をもつという意味での現代的意義をもつこと、などをさまざまな角度から論じている。」

1 0 0 0 OA 田中智志著『他者の喪失から感受へ-近代の教育装置を超えて』

- 著者

- 今井 康雄

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.152-158, 2004-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 池田全之著『自由の根源的地平-フィヒテ知識学の人間形成論的考察』

- 著者

- 増渕 幸男

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.159-161, 2004-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

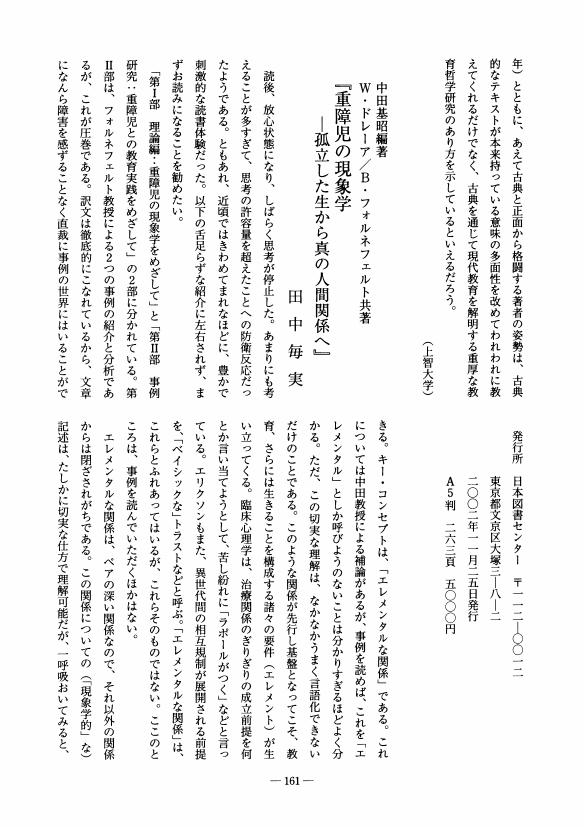

- 著者

- 田中 毎実

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.161-162, 2004-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 山崎高哉編『応答する教育哲学』

- 著者

- 高橋 勝

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.163-164, 2004-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 生きること死ぬこと-日本の自壊 (抄)

- 著者

- 野口 裕之

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.29-41, 2004-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 教育と生死の風景

- 著者

- 和田 修二

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.42-47, 2004-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 課題研究に関する総括的報告

- 著者

- 小笠原 道雄 鈴木 晶子

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.48-52, 2004-05-10 (Released:2009-09-04)

1 0 0 0 OA 二宮尊徳の〈方法〉としてのことば 『三才報徳金毛録』という語り

- 著者

- 中桐 万里子

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.53-68, 2004-05-10 (Released:2010-05-07)

- 参考文献数

- 19

Many studies on Ninomiya Sontoku and his thought- known as “Hotoku-thought” - have attached significance to his “SANSAI-HOTOKU-KINMOUROKU”. But there is hardly any major investigation into this text. This has been the case because the said text was composed in an esoteric style which combined iconographical figures and poetical expressions. The traditional methods of study could not decipher such a style properly. The present paper approaches Sontoku's text from the point of view of “discourse”. The author does not assume that the “discourse” indicates something substantial as well as fixed, objective meanings. As the author has confirmed through a number of clinical-pedagogical case studies, the “discourse” here points to fluid and polysemous meanings, which would depend on actual speaking “scenes” (including daily speaking situations, sounds, shapes, images and so on). Relying on Roman Jacobson (1896 - 1982) who elaborated on the meanings and styles of “discourse” and who emphasized its poetical function, the present author has formulated a hypothesis for interpreting the text “SANSAI-HOTOKU-KINMOUROKU”. She will argue that Sontoku described his outlook on the world (the relation between “jindo” (the human's daily life) and “tendo” (the principle of nature)) by combining iconographical figures and poetical expressions. Furthermore, the present paper clarifies the effect that such an imaginative, iconographical and poetical “discourse” had produced on listeners. Through this study, the author also examines the “discourse” styles of clinical-pedagogy which would depend upon actual, speaker-listener relations.

1 0 0 0 OA アイデンティティ喪失の解釈学 ポール・リクールのアイデンティティ論

- 著者

- 松尾 憲一

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.69-85, 2004-05-10 (Released:2010-05-07)

- 参考文献数

- 31

La débat sur la perte d'identité occupe une place importante dans la pédagogie contemporaine. Cet article a pour but d'approfondir cette réflexion par une clarification du cardre fondamental sur l'identité introduit par Paul Ricceur dans «Soi-même comme un autre», et par un réxamen de son interpretation sur la perte d'identité.D'abord, en vue de clarifier la notion de «perte d'identité» selon Ricceur, je veux dégager le sens des deux concepts fondamentaux de «mêmeté et d'ipséité». La mêmeté est définie comme une relation «seule et méme»qui permet l'identification temporelle, et l'ipséité comme un pouvoir sur soi appelé «attestation» et qui donne une assurance à l'ascription au soi.Ensuite, j'examine les concepts d'identité personnelle et d'identité narrative qui tous deux se rapportent à la notion de l'identité humaine. L'identité personelle est généralement envisagée selon les duex modèles du caractère et de promesse. Dans le caractère, l'ipséitéadhère à la mêmeté mais elle se sépare de la mêmeté au plan de la promesse. L'identité narrative supprime la distance de ces deux modèles. Elle peut intégrer les expériences personelles diverses au moyen de la fonction médiatrice de l'intrigue.Enfin, je traite en détail de l'interprétation sur la perte d'identité chez Ricoeur. C'est la mêmetédu caractère qui se perd définitivement avec la perte d'identité. Mais qu'en est-il de l'ipséiteé? Au contraire de 'Interprétation centrale qui insiste sur la perte de l'ipséité, je propose une interprétation périphérique qui insiste sur le maintien de l'ipséité. Par là, j'essaie d'apporter un éclairage théorique à l'image de l'homme qui échappe sans cesse à cette identité que le débat pédagogique envisage aujourd'hui.

1 0 0 0 OA 宗教教育のトポスを開く語りの可能性 『パンセ』の「自然な文体」を手がかりとして

- 著者

- 河野 洋子

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.86-102, 2004-05-10 (Released:2010-05-07)

- 参考文献数

- 34

This paper examines how Pensées, when it is postulated as a text written in “le style naturel, ” opens up a “topos” for religious education. “Religious education” here refers to the scene which has the effect of promotion among those in the scene a realization of the the limitation of human existence and, moreover, of enhancing their spiritual attitude toward the transcendence.The present author examinees, first, the relationships among “le style naturel, ” “raison, ” “ordre” and “esprit de finesse”. “Le style naturel” presupposes reasonable understanding and, furthermore, leads to the transcendental truth through the realization of the limitation of “raison.” “Esprit de finesse” perceives the “advent/Advent” from the transcendence, and the discourse of “le style naturel” thus work upon readers “volonté” on top of their “raison.” The author, then, examines those discourses including “I” as an essential example of “le style naturel.” According to her interpretation, both an apologist and a libertine are textured in “I” in which they are independent as well as supportive to each other. Moreover, she shows that “un roseau pensant” and “membres pensants”, other examples of “le style naturel, ” also express the human existence as a “texture”.The rhetoric of Pensées point to the “topos” for “advent/Advent” because Pensées contains the “topos” as the texture which produces “le style naturel.” One can say that “le style naturel” is the discourse which may open up the “topos” for religious education. Hence, the quest for this style is crucial for locating the possibilities and methods of religious education.

- 著者

- 松原 岳行

- 出版者

- 教育哲学会

- 雑誌

- 教育哲学研究 (ISSN:03873153)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2004, no.89, pp.103-119, 2004-05-10 (Released:2010-05-07)

- 参考文献数

- 46

“Nietzsche als ErZieher” ist 1914 in der deutschen Pädagogik entstanden. Das ist eine Tatsache in der Geschichte der Nietzsche-Rezeption. Wie aber wurde Nietzsche als Erzieher angesehen? Welche zeitgenossische Bedeutung hatte das Interpretationsmodell “Nietzsche als Erzieher”? Um dieses Problem zu klären - andere als bei Ch. Niemeyer - richte ich mein Augenmerk auf die Phasen der Nietzsche-Rezeption in der deutschen Pädagogik zwischen 1907 und 1914.Bei der Klärung der zeitgenossischer Bedeutung des Interpretationsmodells “Nietzsche als Erzieher”, woran man heute noch festhält, handelt es sich urn eine andere Tatsache in der Geschichte der pädagogischen Nietzsche-Rezeption nämlich das Interpretationsmodell “Nietzsche als Pädagoge”, das E. Weber aufgestellt hat Gegen dieses damals anerkannte Modell gab es aber Kritik; denn das Interpretationsmodell “Nietzsche als Pädagoge” hatte die Domestizierung Nietzsches zur Voraussetzung.Nach der Wende zum 20. Jahrhundert hatte das Wort “Erzieher” bestimmte Sinngebungen. Der “Erzieher” hatte damals das Bedürfnis, lebendig zu sein und ein personliches Verhältnis zum Schüler zu unterhalten. Wie hat Nietzsche die Bedingungen als “Erzieher” erfüllt? In der 1911 erschienenen Abhandlung “Ist Nietzsche wirklich tot?” zweifelte R Oehler an “Nietzsches Tod” und manifestierte “Nietzsches Auferstehung” auf Grund der Verbreitung der Nietzsche-Lektüre in den 1910er Jahren, wodurch Nietzsche ein personliches Verhältnis zu Schülern (jugendlichen Lesern) gewinnen konnte.W. Hammer behandelt in seiner 1914 erschienen Schrift “Nietzsche als Erzieher” die späteren Ideen Nietzsches wie “Übermensch” oder “Moralkritik” und stellte Nietzsche als lebendigen Erzieher dar. Die Schrift “Nietzsche als Erzieher” stellte ein “Manifest der Nietzsches Auferstehung” der auf Grund der Verbreitung der Nietzsche-Lektüre bei der Jugend. Wir konnen “Nietzsche als Erzieher” als eine Alterntive zu der erneut verbeiteten pädagogischen Nietzsche-Interpretation verstehen.Durch einen Vergleich beides Interpretationsmodelle “Nietzsche als Pädagoge” (1907) und “Nietzsche als Erzieher” (1914), versuche ich andeutungsweise die Moglichkeit einer Beziehung zwischen der heutige Pädagogik und Nietzsche aufzuzeigen.