1 0 0 0 歐舶來航前後の東洋に於ける海上貿易(二・完)

- 著者

- 秋山 謙藏

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.5, no.6, pp.629-646, 1935

1 0 0 0 中世の職人氣質と其根據

- 著者

- 本位田 祥男

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.4, no.4, pp.357-373, 1934

1 0 0 0 OA 中国の祭祀共同体について (社会経済史の構成方法を求めて : 具体的事例に即して)

- 著者

- 斯波 義信

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.44, no.4, pp.411-419, 1979-01-10 (Released:2017-11-24)

1 0 0 0 アント人の種族同盟の基礎

- 著者

- 阿部 重雄

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.18, no.4, pp.340-352, 1952

1 0 0 0 OA 昭和恐慌と日本綿業 第11次操業短縮と服部商店

- 著者

- 橋口 勝利

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.82, no.3, pp.249-271, 2016 (Released:2018-11-25)

- 著者

- チャウドゥリ K. N. 川勝 平太

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.51, no.1, pp.1-16, 1985

This paper argues that the transition from pre-modern trade to post-Industrial Revolution trade in Asia and indeed in the world generally incorporated a fundamental change in its causation. Pre-modern trade was essentially derived from socially-determined demand arising out of cultural habits and interpretations, but of course, the force of demand operated through market forces and relative prices. Nineteenth-century international trade, on the other hand, was founded on the supply and the production side of the world economy. The fundamental changes in the system of economic production based on the application of machinery and the capitalist organisation made movements of industrial raw materials, food stuffs, and even manufactured goods appear as induced effects of the needs of producers to keep production going. In the pre-modern period, the thinking of merchants and others involved in the business of distant trade, was overwhelmingly influenced by demand factors. This is far removed from the present-day situation in which international trade is primarily a function of the relative distribution of technological endowments. In the earlier period, the technology of production had stabilised itself over many centuries and was treated as if it was a constant. The force of change and the opportunity for accumulating wealth came mainly from shifts in demand and an improvement in the institutional arrangements of economic exchange which lowered costs. There is little disagreement among historians that Asia's inter-regional trade underwent a profound change between 1800 and 1900. The transformation touched both the direction and the composision of goods exchanged. The payments mechanism itself gave rise to induced changes and brought into being the famous trian gular commercial relations between India, China, and Britain, which developed into a true multilateral systems of trade and payments mechanism during the second half of the nineteenth century. Imperialism as an economic force fused together with its political manifestations to form the most powerful historical phenomenon of the time.

- 著者

- 大田 由紀夫

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.61, no.2, pp.156-184,282, 1995

It is well known that the copper cash minted by successive Chinese dynasties circulated throughout East Asia. However, the actual patterns of circulation have not been fully researched. This article approaches the subject by referring to the movement of currency in the Japanese Medieval period. There were two periods, from 1215 to 1225 and in the 1270s, when copper cash circulated actively in Japan. On both occasions this was because of large outflows of copper cash from China after it had been banned and was therefore not in demand, in northern China under the reign of the Chin dynasty in the first case and in Chiangnan region under the reign of the Yuan dynasty in the second case While the introduction of the copper cash from China encouraged a remarkable development of the market economy in Japan, it also disturbed the established political and social order. After this, the movements of Chinese currency continued to have a great influence on Japanese currency, as when the early Ming seclusion policy led to a decline in the inflow of copper cash into Japan. Furthermore, the fact that Chinese copper cash only became a principal currency in Japan when it ceased to be a means of payment to and by the state in China, clearly shows that the circulation of Chinese copper cash in Medieval Japan did not signify the incorporation of Japan into the internal Chinese currency system.

- 著者

- 永島 剛

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.75, no.3, pp.354-356, 2009

- 著者

- 郭 まいか

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.84, no.1, pp.25-43, 2018

- 著者

- 友部 謙一

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.54, no.2, pp.250-270,304, 1988

The purpose of this paper is to explore a mechanism of family labour distribution to farming and non-farming activities in a peasant family economy and to find out a relation between an amount of family landholing and family life-cycle in a peasant family household. As for the first problem, peasant family households distributed their total family labour to farming and non-farming activities in order to increase their total incomes. The mechanism of family labour distribution owed to "Chayanov-Rule" (by M. SHALINS) in farming activities and to "Douglas-Arisawa Findings" in the choice of non-farming ones. Concerning to the second problem, peasant family households changed amounts of their landholding to their C-P ratio (a ratio of consumers index to producers index within a family household). This relationship also materializes an inter-household collectivity in a Tokugawa village life,. So it will do much for the development of quantitative veserdhes in historical sociology of Tokugawa Japan. Additionally these findings appeal the usefulness of quantitative methods and the importance of logical thought in historical researches, and the other hand they cast the doubt on traditional views of the Tokugawa peasantry.

- 著者

- 鈴木 恒之

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.64, no.6, pp.886-888, 1999-03-25 (Released:2017-08-22)

- 著者

- 谷本 雅之

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.64, no.1, pp.88-114,164, 1998

The movement to establish modern enterprises in Meiji Japan was found in rural as well as urban areas. This was made financially possible through the willingness of men of property based in rural areas to invest their capital in such risky ventures. The purpose of this paper is to point out that the motivation behind these activities was linked to the existence of "local society". First, about 250 major stockholders in Niigata prefecture were classified into four groups according to the nature of their stockholdings in 1901. This demonstrated that a significant number of men of property had invested their money in the high risk stocks of local enterprises. Next, case studies were made of two local entrepreneur families, the HAMAGUCHI and the SEKIGUCHI. Both families invested the capital accumulated through their family business of soy sauce brewing in new enterprises and businesses in their local area in the 1890s. In parallel with these business activities, they vigorously participated in local social and political activities. These case studies showed us that their investment activities were closely related to their social and political activities. As these activities were so interlocked in the local areas, we conclude that the existence of "local society", which recent historical studies show to have emerged in the latter half of the nineteenth century, encouraged men of property to invest in local enterprises. "Local society as the spur to enterprise investment" is our contribution to the main theme of this symposium.

1 0 0 0 江戸時代貨幣表の再検討

- 著者

- 田谷 博吉

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.39, no.3, pp.261-279, 1973

- 被引用文献数

- 1

During the Edo period, the leading currencies were gold, silver, and copper coins issued by the Tokugawa Shogunate. Though various kinds of paper money were issued by territorial lords (Daimyo) especially in the latter half of the Edo period, it was necessary to obtain the permit of the Shogunate to issue money. In commercial transactions, the most important currencies were gold and silver coins of the Shogunate, which were produced in more than 40 different kinds. In order to study the monetary transactions of the period, it is therefore necessary to classify these various sorts of coins by the time of issue (Keicho, Genroku-Hoei, Shotoku-Kyohou, Genbun, Bunsei, Tenpo, Ansei-Manyen) and show the date of issue, the years of circulation, the weight and fineness, the amount of issue, etc. There are two kinds of currency table showing the above items : one made by Chuzaburo Sato, an official of the mint of gold coins of the Shogunate, in 1873; and the other by the Osaka Mint of the Meiji government in 1921.Though the one made by Chuzaburo Sato is more useful to the study of Tokugawa currency, his table is based on the materials in the last part of the Edo period. The present writer constructs a new table using earlie source materials in this paper.

1 0 0 0 OA 星埜惇著 『社会構成体移行論序説』

- 著者

- 永原 慶二

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.35, no.5-6, pp.575-578, 1970-03-20 (Released:2017-08-03)

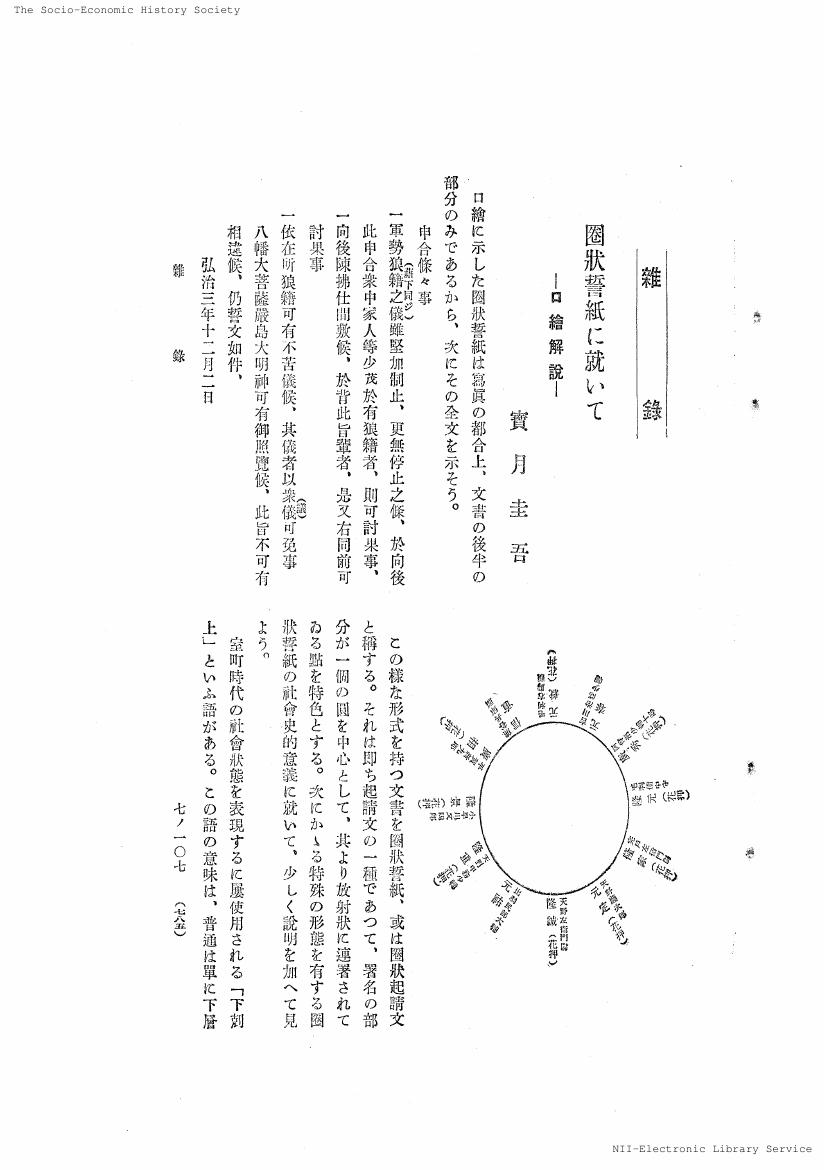

1 0 0 0 OA 圈状誓紙に就いて : 口繪解説

- 著者

- 寶月 圭吾

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.3, no.7, pp.785-789, 1933-10-15 (Released:2017-09-25)

1 0 0 0 奧羽文化移植の過程

- 著者

- 大島 延次郎

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.13, no.2, pp.135-139, 1943

- 著者

- 田島 佳也

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.46, no.3, pp.293-321,374-37, 1980

The purpose of this article is to survey the management of basho (fishing territories) by Eiyemon Sato who was a contractor for the fishery at Utasutu and Isoya basho in the late Edo period after 1853, and to bring to light the way the fishermen worked for the contractor positively through various books concerning their management. Approaches will be made to the Sotos as a center, to those fishermen employed by the Satos, and to hamaju fishermen including ni-hachi fishermen, who paid twenty percent of his catch to the contractor. Following is the outline of this article. Since basho were bases of fishery devoid of reproducing conditions, the Satos, beside pursuing fishing mainly of herring themselves, catch of which was diminishing, laid daily necessaries and means of production in stock and sold them. Judging from this operation, the fishermen directly employed by the Satos and hamaju fishermen were essential to the Satos' management of basho. Among the fishermen directly employod there were two categories: one, called bannin (watchman or foreman), was employed by the year and the other, called yatoinin (employee), by the season. Though most of them came from Shimokita district alike, the former was to a greater extent personally subordinate in master-and-servant relationship, while the latter actually had characteristics somewhat similar to those of a wage labourer. On the other hand, hamaju fishermen included permanent residents and those who were temporarily working away from home, both of whom came mostly from Matsumae district. In the late Edo period there appeared those who, together with their wife and children, emigrated and worked away from home. Some of them, having started as small fishermen, were successful enough to cope with the contractor, and with their developing productivity they grew to be main members of the economy at basho. In keeping with this change, the Satos shifted the Center of their management from fishery to providing people with daily necessaries and means of production. In conclusion the Satos manoeuvred to control the labour through tension among the fishermen which was caused by the difference in their geographical origins. They employed the fishermen whose home villages were different from those of hamaju fishermen, intending to exclude the fishermen's mutual bond caused by local connection. The Satos strengthened managerial role of bannin and shifted the center of their activities on hamaju fishermen who had been getting independent from the contractor. The nature of the existence of those hamaju fishermen can be explained first by the glowth of reproducing conditions at basho, and secondly by the support of the shogunate that governed Ezo district and sought measures of distribution fitting for fishery.

- 著者

- 星野 高徳

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.87, no.2, pp.171-195, 2021

- 著者

- 奥田 伸子

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.75, no.2, pp.236-238, 2009

- 著者

- 西川 洋一

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.68, no.2, pp.237-239, 2002