- 著者

- 郭 まいか

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.84, no.1, pp.25-43, 2018

- 著者

- 友部 謙一

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.54, no.2, pp.250-270,304, 1988

The purpose of this paper is to explore a mechanism of family labour distribution to farming and non-farming activities in a peasant family economy and to find out a relation between an amount of family landholing and family life-cycle in a peasant family household. As for the first problem, peasant family households distributed their total family labour to farming and non-farming activities in order to increase their total incomes. The mechanism of family labour distribution owed to "Chayanov-Rule" (by M. SHALINS) in farming activities and to "Douglas-Arisawa Findings" in the choice of non-farming ones. Concerning to the second problem, peasant family households changed amounts of their landholding to their C-P ratio (a ratio of consumers index to producers index within a family household). This relationship also materializes an inter-household collectivity in a Tokugawa village life,. So it will do much for the development of quantitative veserdhes in historical sociology of Tokugawa Japan. Additionally these findings appeal the usefulness of quantitative methods and the importance of logical thought in historical researches, and the other hand they cast the doubt on traditional views of the Tokugawa peasantry.

- 著者

- 鈴木 恒之

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.64, no.6, pp.886-888, 1999-03-25 (Released:2017-08-22)

- 著者

- 谷本 雅之

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.64, no.1, pp.88-114,164, 1998

The movement to establish modern enterprises in Meiji Japan was found in rural as well as urban areas. This was made financially possible through the willingness of men of property based in rural areas to invest their capital in such risky ventures. The purpose of this paper is to point out that the motivation behind these activities was linked to the existence of "local society". First, about 250 major stockholders in Niigata prefecture were classified into four groups according to the nature of their stockholdings in 1901. This demonstrated that a significant number of men of property had invested their money in the high risk stocks of local enterprises. Next, case studies were made of two local entrepreneur families, the HAMAGUCHI and the SEKIGUCHI. Both families invested the capital accumulated through their family business of soy sauce brewing in new enterprises and businesses in their local area in the 1890s. In parallel with these business activities, they vigorously participated in local social and political activities. These case studies showed us that their investment activities were closely related to their social and political activities. As these activities were so interlocked in the local areas, we conclude that the existence of "local society", which recent historical studies show to have emerged in the latter half of the nineteenth century, encouraged men of property to invest in local enterprises. "Local society as the spur to enterprise investment" is our contribution to the main theme of this symposium.

1 0 0 0 江戸時代貨幣表の再検討

- 著者

- 田谷 博吉

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.39, no.3, pp.261-279, 1973

- 被引用文献数

- 1

During the Edo period, the leading currencies were gold, silver, and copper coins issued by the Tokugawa Shogunate. Though various kinds of paper money were issued by territorial lords (Daimyo) especially in the latter half of the Edo period, it was necessary to obtain the permit of the Shogunate to issue money. In commercial transactions, the most important currencies were gold and silver coins of the Shogunate, which were produced in more than 40 different kinds. In order to study the monetary transactions of the period, it is therefore necessary to classify these various sorts of coins by the time of issue (Keicho, Genroku-Hoei, Shotoku-Kyohou, Genbun, Bunsei, Tenpo, Ansei-Manyen) and show the date of issue, the years of circulation, the weight and fineness, the amount of issue, etc. There are two kinds of currency table showing the above items : one made by Chuzaburo Sato, an official of the mint of gold coins of the Shogunate, in 1873; and the other by the Osaka Mint of the Meiji government in 1921.Though the one made by Chuzaburo Sato is more useful to the study of Tokugawa currency, his table is based on the materials in the last part of the Edo period. The present writer constructs a new table using earlie source materials in this paper.

1 0 0 0 OA 星埜惇著 『社会構成体移行論序説』

- 著者

- 永原 慶二

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.35, no.5-6, pp.575-578, 1970-03-20 (Released:2017-08-03)

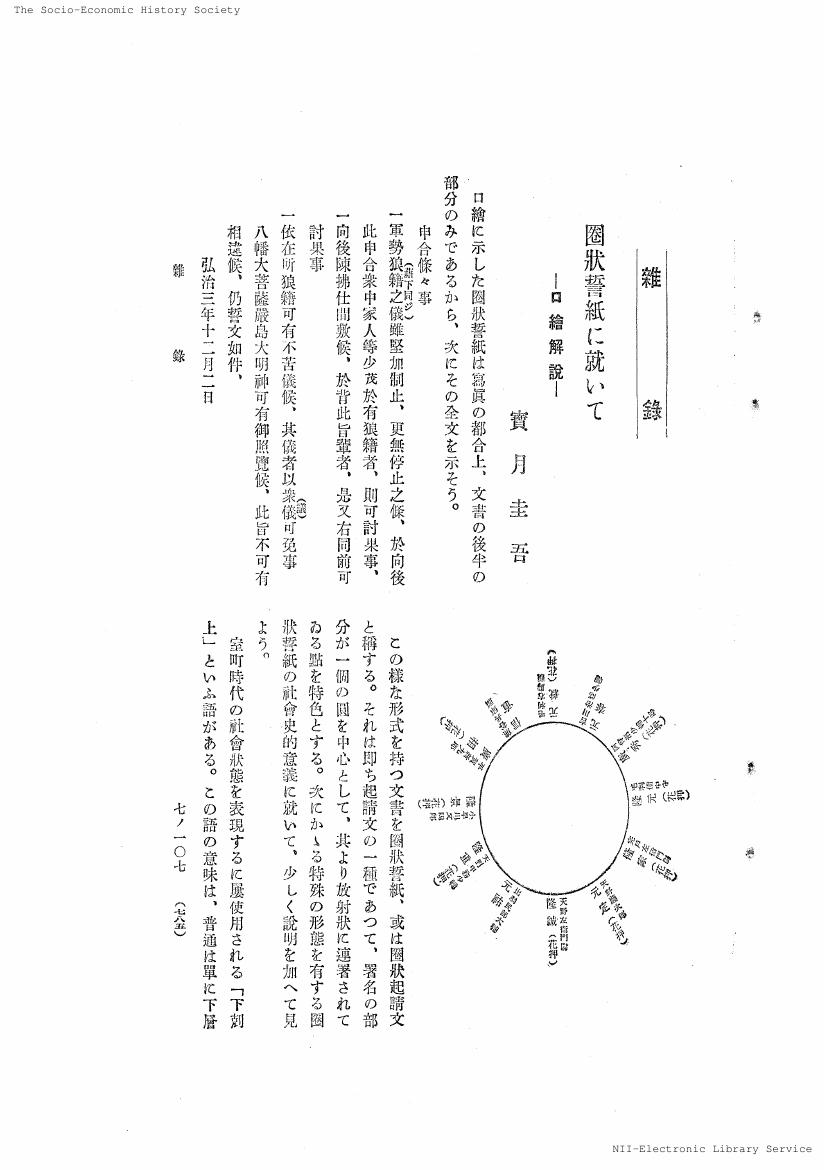

1 0 0 0 OA 圈状誓紙に就いて : 口繪解説

- 著者

- 寶月 圭吾

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.3, no.7, pp.785-789, 1933-10-15 (Released:2017-09-25)

1 0 0 0 奧羽文化移植の過程

- 著者

- 大島 延次郎

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.13, no.2, pp.135-139, 1943

- 著者

- 田島 佳也

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.46, no.3, pp.293-321,374-37, 1980

The purpose of this article is to survey the management of basho (fishing territories) by Eiyemon Sato who was a contractor for the fishery at Utasutu and Isoya basho in the late Edo period after 1853, and to bring to light the way the fishermen worked for the contractor positively through various books concerning their management. Approaches will be made to the Sotos as a center, to those fishermen employed by the Satos, and to hamaju fishermen including ni-hachi fishermen, who paid twenty percent of his catch to the contractor. Following is the outline of this article. Since basho were bases of fishery devoid of reproducing conditions, the Satos, beside pursuing fishing mainly of herring themselves, catch of which was diminishing, laid daily necessaries and means of production in stock and sold them. Judging from this operation, the fishermen directly employed by the Satos and hamaju fishermen were essential to the Satos' management of basho. Among the fishermen directly employod there were two categories: one, called bannin (watchman or foreman), was employed by the year and the other, called yatoinin (employee), by the season. Though most of them came from Shimokita district alike, the former was to a greater extent personally subordinate in master-and-servant relationship, while the latter actually had characteristics somewhat similar to those of a wage labourer. On the other hand, hamaju fishermen included permanent residents and those who were temporarily working away from home, both of whom came mostly from Matsumae district. In the late Edo period there appeared those who, together with their wife and children, emigrated and worked away from home. Some of them, having started as small fishermen, were successful enough to cope with the contractor, and with their developing productivity they grew to be main members of the economy at basho. In keeping with this change, the Satos shifted the Center of their management from fishery to providing people with daily necessaries and means of production. In conclusion the Satos manoeuvred to control the labour through tension among the fishermen which was caused by the difference in their geographical origins. They employed the fishermen whose home villages were different from those of hamaju fishermen, intending to exclude the fishermen's mutual bond caused by local connection. The Satos strengthened managerial role of bannin and shifted the center of their activities on hamaju fishermen who had been getting independent from the contractor. The nature of the existence of those hamaju fishermen can be explained first by the glowth of reproducing conditions at basho, and secondly by the support of the shogunate that governed Ezo district and sought measures of distribution fitting for fishery.

- 著者

- 星野 高徳

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.87, no.2, pp.171-195, 2021

- 著者

- 奥田 伸子

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.75, no.2, pp.236-238, 2009

- 著者

- 西川 洋一

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.68, no.2, pp.237-239, 2002

1 0 0 0 OA 在来織物業の技術革新と化学染料 : 伝統色から流行色へ

- 著者

- 田村 均

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.69, no.6, pp.645-670, 2004-03-25 (Released:2017-06-16)

The introduction of chemical dyeing materials in order to develop new textile products had a great influence on the domestic fashion textiles market in early Meiji Japan. This paper investigates how the possibility of new dyes encouraged technological growth in regional silk production districts as well as in dominant Japanese textile production centers such as Nishijin, Kiryu, and Ashikaga. In the years after the competitive exhibition in 1885, several regional silk production districts developed new textile products by introducing new technology in the form of chemical dyeing materials from Western Europe. In particular, the most active local districts such as Hachioji, Isesaki, and Tokamachi, succeeded in developing new fashions through the production of new textiles that were of high quality in terms of weaving, yarn quality, dyeing, weight, design, and price. On the other hand, regional silk production districts which had neglected to introduce newtechnology simply stagnated or declined. High quality newtextiles with fashionable designs were essential to the development of the textile industry in Japan.

1 0 0 0 OA 「城防」から見る清代城郭都市の一側面 : 広州を中心として

- 著者

- 梁 敏玲

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.79, no.3, pp.333-352, 2013-11-25 (Released:2017-05-17)

本稿は,広東省の省城広州を事例とし,「城防」(城壁都市の守備・治安維持)という面から清代城郭都市の一端を明らかにしようとするものである。帝政時代の中国では,一般に官庁所在地は城壁によって囲まれており,行政拠点である城の守備を目的として軍隊・防衛施設が設置されていた。清代の広州城には,八旗・緑営の双方が駐屯し,更に緑営の中でも,一般緑営軍制の一部として各城に配置される城守協のほか,八旗将軍直属の緑営軍隊や,広東巡撫(1746年から両広総督も広州に移駐)及びその直属の緑営軍隊も広州城に駐屯していた。城防は異なる系統の軍隊によって行われており,諸系統が各自の管轄区域を持ち,互いの間に直接・間接の上下関係があった。八旗の緑営に対する監視・コントロールや諸系統の相互の制御・協力から見れば,このような城防は緊密に構造化された体系ではなく,むしろそれぞれが中央と結びついた各種の軍隊からなる緩い集合体であった。長い平和期の間に,柔軟性を持つ城防システム内部では,状況に対応しつつ様々な調整が行われており,その過程で,八旗の駐屯はより象徴的な存在となってきたといえる。

1 0 0 0 出土六道銭の組合せからみた江戸時代前期の銅銭流通

- 著者

- 鈴木 公雄

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.53, no.6, pp.749-775, 1988

Although the significance of the archaeological approaches has been neglected in the historical study of the Edo period, the present paper, by combining archaeological materials with historical documents, aims at illuminating the Tokugawa government's monetary policy in the seventeenth century. Numerous copper currencies discovered from 153 graves of that period are undoubtedly important archaeological materials to specify the currencies in circulation. These currencies called Rokudosen (六道銭), buried as grave goods, can be classified into the four major types: the imported Chinese currencies (Toraisen 渡来銭), Kokan'eitsuho (古寛永通宝 first issued in 1636), Bunsen (文銭 in 1668) and Shinkan'eitstuho (新寛永通宝 in 1697). The patterns of their frequency distributions, analyzed by "frequency seriation" which is commonly used in the chronological study of prehistoric archaeology, indicate that the replacement of Toraisen by Kokan'eitstuho was achieved promptly. On the other hand, the transition from Kokan'eitsuho to Bunsen and from Bunsen to Shinkan'eitsuho required rather long duration. It is worth noting that the above observation corresponds to the descriptions of some historical documents on the government's monetary policy. The documents such as Shukubashiryo (宿場史料) indicate that the government intended to exclude the older, imported currencies, and that the government prohibited their use in 1670. The validity of these descriptions was hardly demonstrated in the previous studies; however, the result of "frequency seriation" obtained from the excavated currencies represents that the government's policy was effectively carried out. The consistency of the government's monetary policy, which is partly reflected in some documents, can be more clearly characterized by synthesizing both archaeological and historical evidence.

1 0 0 0 正田健一郎先生を悼む

- 著者

- 清水 元

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社會經濟史學 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.77, no.3, 2011-11-25

- 著者

- 今津 健治

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.62, no.4, pp.542-544, 1996

1 0 0 0 OA インドにおける財閥の出自について : 十九世紀〜第一次大戦

- 著者

- 伊藤 正二

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.45, no.5, pp.511-536,599-59, 1980-02-29 (Released:2017-07-15)

Most of the Indian zaibatstu, the owners of the larger industrial houses of present day India belong, community-wise, to the Marwaris, the Gujerati-Banyas, or the Parsis. This article examines the nature of business activity and institution of each of these three major business communities just before and after the time of their entry into modern industrial enterprises, i.e., around the middle of the 19th century in the case of the Parsis and the Gujerati-Banyas and at the turn of the present century in the case of the Marwaris. The main purpose of this article is to find out that these communities shared some common features when they entered the modern industrial fields in spite that they did so, as is well known, at different times and through different paths. The conclusions are as follow; Firstly, the fact that most of the owners of the present day Indian zaibatsu belong to a very few particular business cnmmunities originates from the historical facts that only the large scale merchant capitalists were in a position to start modern industry in the backward and colonial economy and that a few business communities dominated the industrial fields right from the beginning of the Indian modern industrial capitalism. Secondly, the success as prominent merchant class by the particular communities, especially the Marwaris and the Chettiars, and perhaps all the other successful business communities, was not a little due to existence of some kind or other of the institutions that accomodated unsparingly the needs and wants of their own communities' members. Thirdly, those merchants wgre no doubt basically compradors. But the few Parsis and Marwaris that first ventured in modern industry had been of less comprador nature: They had been engaged in such relatively independent business as foreign trade on their own account, or speculation on large scale. This article, en Passant, notes that absorption and amalgamation movement was not so unimportant a factor, as is usually argued, for bringing forth the larger managing agency houses so far as the cotton textile industry of Bombay, the strong-hold of Indian capitalists, during the nineteenth century is concerned. There occurred very many failures of the cotton mills then, which certainly helped some of the mnaging agency houses to emerge as dominant ones.

- 著者

- 植田 展大

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.86, no.1, pp.49-70, 2020

1 0 0 0 近世後期における貰魚慣行の変遷:豆州内浦地域を事例として

- 著者

- 高橋 美貴

- 出版者

- 社会経済史学会

- 雑誌

- 社会経済史学 (ISSN:00380113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.85, no.4, pp.419-442, 2020