2 0 0 0 OA 西欧・南欧(中世,ヨーロッパ,二〇一〇年の歴史学界-回顧と展望-)

- 著者

- 近江 吉明

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.120, no.5, pp.940-945, 2011-05-20 (Released:2017-12-01)

2 0 0 0 OA 公議輿論と万機親裁 : 明治初年の立憲政体導入問題と元田永孚

- 著者

- 池田 勇太

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.115, no.6, pp.1041-1078, 2006-06-20 (Released:2017-12-01)

The present article attempts to clarify the birth of monarchical constitutionalism on the occasion of a debate over a popularly elected parliament in 1874, by focusing on Motoda Nagazane (or Eifu) 元田永孚, who was Emperor Meiji's tutor in Confucianism. The introduction of a constitutional polity in the absence of a government not only displayed the strong character of a modernization measure and was thought to realize a political society supported by the masses and open public opinion, but also a parliament, constitution and separation of the legislative and administrative branches of government were expected to solve real problems that existed in local administration and politics at the time. The article begins with an examination of the actions taken by the Governor of Fukushima Prefecture Yasuba Yasukazu 安場保和 in order to clarify the era's parliamentary movement against the background of local administration and to argue that the fair and just nature (ko 公) of a constitutional polity was thought to be identical to traditional Confucian political ideals. Secondly, the introduction of a constitutional polity at that point in time was not the result of power politics fought along vertical, class lines, but was rather a specific political expression of what the Restoration bureaucracy thought desirable. On the other hand, the introduction of such a polity under well-meaning auspices from above also meant that the bureaucracy did not always seek broad pluralistic opinions on the subject, but rather tended to make policy decisions in a more theoretical manner. The 1874 debate over a popularly elected parliament brought the issue of mass popular political participation to the forefront in terms of "joint rule by king and citizen." It was here that Motoda Eifu suggested that in a monarchical state it was necessary to make a distinction between "public opinion" and "the just argument," arguing that it was the monarch who should employ the latter. Any parliamentary system in which the monarch enjoys ultimate prerogative, moreover, demands that the monarch have the ability to exercise that prerogative properly, which necessitated the development of a system of imperial advisors and educators. At that time there was also the idea that the position of senior political advisor (genro 元老) should be created outside of the cabinet to perform such a function. Motoda, on the other hand, reformed such an idea based on the necessity of a monarch performing his duties with the final say within a constitutional polity. This is why it can be said that both monarchical constitutionalism and the establishment of the emperor's prerogative within it was born out of the 1874 debate over a popularly elected parliament.

2 0 0 0 OA 初期中世アイルランドにおける婚姻と女性の権利 : 『アイルランド教会法令集』を通して

- 著者

- 田付 秋子

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.108, no.12, pp.2177-2178, 1999-12-20 (Released:2017-11-30)

2 0 0 0 歴史理論 (1976年の歴史学界--回顧と展望)

- 著者

- 堀越 孝一

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.86, no.5, pp.p500-504, 1977-05

- 著者

- 紺谷 由紀

- 出版者

- 史学会 ; 1889-

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.125, no.6, pp.1053-1088, 2016-06

2 0 0 0 守護支配の展開と知行制の変質

- 著者

- 岸田 裕之

- 出版者

- 山川出版社

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.82, no.11, pp.1-42, 1973-11

- 著者

- 水間 大輔

- 出版者

- 史学会 ; 1889-

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.125, no.8, pp.1446-1455, 2016-08

2 0 0 0 書評 山川均著『石塔造立』

- 著者

- 大塚 紀弘

- 出版者

- 史学会 ; 1889-

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.125, no.6, pp.1120-1129, 2016-06

2 0 0 0 ミッレト制研究とオスマン帝国下の非ムスリム共同体

- 著者

- 上野 雅由樹

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.119, no.11, pp.1870-1887, 2010-11

- 著者

- 高山 博

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.92, no.11, pp.1815-1816, 1983

2 0 0 0 歴史の風 日食をめぐる興味深い問題

- 著者

- 平勢 隆郎

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.115, no.3, pp.319-321, 2006-03

1 0 0 0 OA 網野善彦著『日本中世の非農業民と天皇』

- 著者

- 永原 慶二

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.93, no.12, pp.1928-1937, 1984-12-20 (Released:2017-11-29)

1 0 0 0 OA 唐から見たエミシ : 中国史料の分析を通して

- 著者

- 河内 春人

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.113, no.1, pp.43-61, 2004-01-20 (Released:2017-12-01)

The Emishi 蝦夷, who resided in the northeast portion of the Jap-anese archipelago, appear in the Chinese sources both as "Emishi" and as "Mojin" 毛人. The description of the former includes their geographical location, customs and year of arrival in China, while the latter merely mentions them as living in northeastern Japan. All of this information was amassed from interviews with foreign emissaries to the Tang Dynasty. Regarding the Emishi, there are both Chinese and Japanese records of them accompanying an envoy from the land of Wa 倭 (Japan) in the year AD 659 and also an account of the Chinese inquiring about them from a Japanese envoy in AD 702 ; however, the latter account, which appears in Shin-Tojo 新唐書, cannot be verified, so 659 is the only time that Emishi became part of a Japanese envoy to China. The information concerning Emishi customs in the Chinese sources matches the content of the report submitted by the 659 Wa envoy to China ; and all of it is characterized by them being introduced through Japan. In particular, the inclusion of Emishi in the 659 envoy was politically motivated to create the image of Wa/Japan as a great empire, but the Tang Dynasty was not impressed. As a result, the Japanese were unable to realize their diplomatic goals, and a gap appeared in the international relations between the two countries. While the Japanese expressed the term "Emishi" with the characters 蝦夷, there is also the strong opinion that the characters 蝦〓 were originally used. However, the source for such an argument being the historically spurious Shin-Tojo, there is no other source to prove that ; and the manuscript of the Nihon Shoki 日本書紀 expresses the term with different characters. The expression 蝦夷 appeared during the late seventh century, together with the creation of a Wa/Japanese ideology concerning its frontiers, leading to the move to take Emishi to China. However, the existence of the Emishi in Tang-Wa diplomacy following the Japan defeat at the Hakuson 白村 River in Korea, had to be covered up, as the term Mojin came into use at the time of the Taiho era Japanese envoys to China. After that time, no new information about the people of northeastern Japan surfaced in Tang China.

1 0 0 0 OA 蓁・漢初における県の「士吏」

- 著者

- 水間 大輔

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.120, no.2, pp.180-202, 2011-02-20 (Released:2017-12-01)

In Han 漢 wooden strips from Juyan 居延 and Dunhuang 敦煌 there are mentioned officials attached to a houguan 候官 who are referred to as shili 士吏. "Shili" is also mentioned in Qin 秦 bamboo strips from Shuihudi 睡虎地 and Han bamboo strips from Zhangjiashan 張家山, but here most of them appear as county (xian県) officials. In past research it has been assumed that shili similar to those attached to a houguan were also assigned to counties. In a previous article, however, the author has pointed out that county-based shili, unlike the shili attached to a houguan, was not the name of an official post but rather a collective term for a group of officials, and that at the very least, the xiaozhang 校長, or head, of a local police station (ting帝) was included among these officials. This article examines what sort of officials were actually designated as this group of county officials known as shili. After an analysis of examples of the use of shili with reference to counties, the author concludes that they were officials who met at least all of the following six conditions: (1) they were under the command of the county defender (xianwei県尉) ; (2) they had jurisdiction over a district; (3) their responsibilities consisted of military duties and police work; (4) in places at some distance from the county office, they were authorized to hear legal charges and complaints, and accept voluntary surrenders to the authorities; (5) their duties included the dispatch of manpower to meet state needs; and (6) they had to be junior subalterns (shaoli小吏) other than those known as sefu 嗇夫. According to these conditions shili might also have subsumed such officials as jiazou 駕〓, maozhang 〓長 and hou 候. The officials subsumed under county-based shili had in common duties (3)-(5) mentioned above; and (3), in particular, involved patrols and the pursuit and arrest of criminals. It is already known that the duties of county defenders included military affairs and police work, and it is evident that these duties were discharged primarily through shili. The last instance of the word shili used as a collective term is found in the Ernian Luling 二年律令 codes. The author surmises from this disappearance that because of growing domestic stability, the military preparedness of counties was thereafter gradually scaled down, and the majority of official posts included among shili were abolished. Therefore, shili as a collective term was no longer needed and fell into disuse.

1 0 0 0 OA 大正期における後藤新平をめぐる政治状況

- 著者

- 季武 嘉也

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.96, no.6, pp.979-1009,1105-, 1987-06-20 (Released:2017-11-29)

From the late years of Meiji to the Taisho period, Goto was brilliantly active in such fields as colonial policy, transportation policy, foreign policy and National Enlightenment. As a politician as well, he had an unusually unique and splendid political career, joining Katsura's New Party, serving first as the Home Minister under Terauchi's "National Unity" Cabinet and again under the second Yamamoto "National Unity" Cabinet, and joining the movement of the Preliminary Committee on universal Suffrage. Previous studies on Goto have been so mesmerized by this brilliance that they have consequently neglected the fundamental problem of his basic political attitude or his position in the political arena during this period. This article represents an exhaustive reconsideration of his political activity. The conclusions reached herein may be summarized as follows : first, concerning Goto's fundamental political attitude, we find that his basic goal was that, rather than the military and political foreign expansion which Japan had been continuously carrying out since the Meiji Restoration, Japan needed to realize external economic expansion and thus truly. become an accepted member of the inner circle of most powerful nations, and a State relatively independent of the Western powers. Secondly, he had a strong interest in the National People's Organization that would be able to realize this goal. It was most characteristic of him at this time that he tried to mobilize scholars and journalists, regardless of their political persuasion or ideology, and to organize, according to their age or ability, those people (for example, members of youth organizations, physicians, educators, etc.) those who were even more committed to the localities than were the class of so-called "Chiho Meiboka". He also cooperated with men such as Okuma Shigenobu and Tanaka Giichi. But it was not possible to fully organize the nation in the Japan of his day. If we look next at his activities within the political arena, we notice that, first, in order to accomplish his goal, he responded to the power of the political parties and the bureaucracy with great flexibility. In particular, he was on constantly good terms with party politicians of the Seiyukai and the Kenseikai. Further, due to his emphasis on "reform", he had many supporters in both the bureaucracy and in the political parties that served him well as a political asset. However, the expectations of his supporters were varied and he ultimately failed to meet them all. Thirdly, and most importantly, he placed the greatest political importance on cooperation with Inukai Tsuyoshi and Ito Miyoji (the "Triangular Alliance"). Moreover, he fundamentally tried to adiministrate political affairs in tune with them and men of the same generation (including the Head of the Seiyukai, Hara Kei, and the Head of the Kenseikai, Kato Takaaki). However, the Second Constitutional Preservation Movement rendered support of his third position difficult. Finally, in the end, this significancy reduced Goto's political power and fixed his place in history as only a minor politician on the periphery of the Seiyukai.

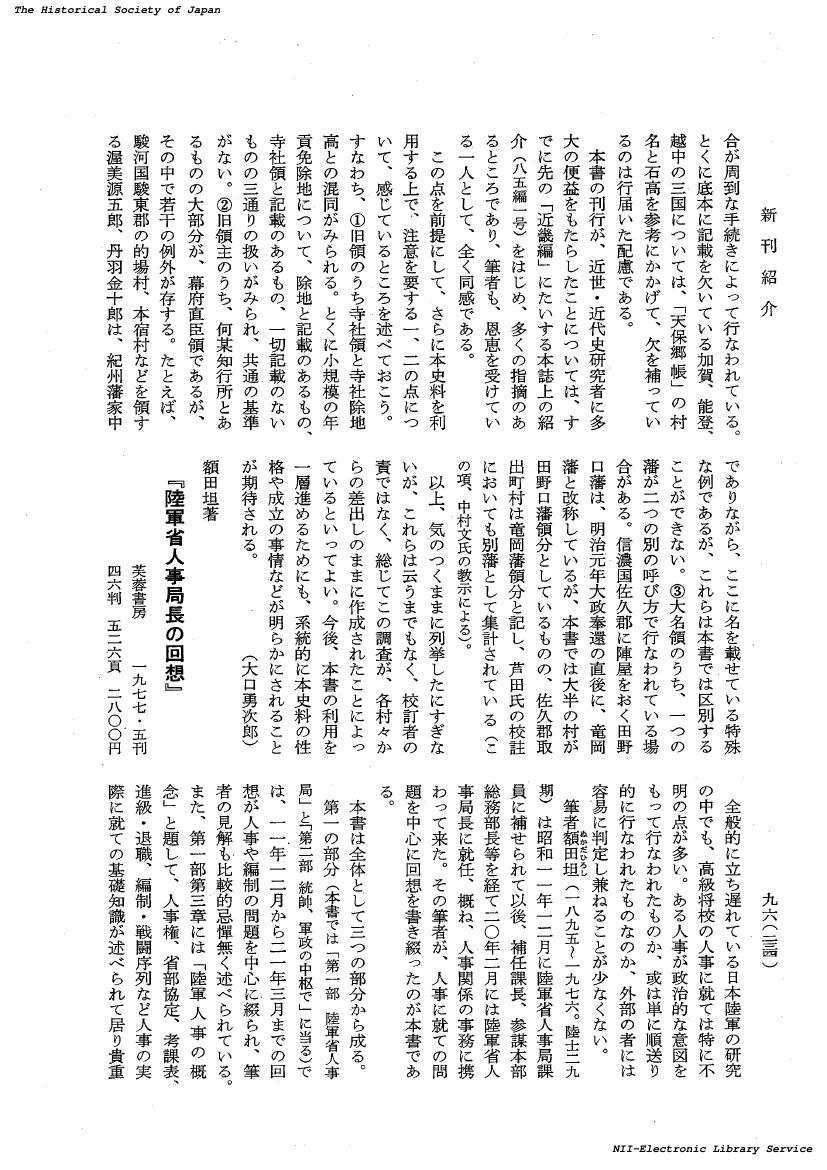

1 0 0 0 OA 額田坦著『陸軍省人事局長の回想』, 芙蓉書房, 一九七七・五刊, 四六判, 五二六頁

- 著者

- 佐々木 隆

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.87, no.2, pp.234-235, 1978-02-20 (Released:2017-10-05)

1 0 0 0 OA 東三省政権をめぐる東アジア国際政治と楊宇霆

- 著者

- 樋口 秀実

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.113, no.7, pp.1223-1258, 2004-07-20 (Released:2017-12-01)

The research to date dealing with the assassination of Yang Yuting by order of Zhang Xueliang on 10 January 1929 focuses on the belief that Yang was pro-Japanese. What the research fails to consider, however, is the assassination of Chang Yinhuai on that same date, which pan by no means be attributed to pro-Japanese sentiment, since Chang never studied in Japan, which is the only proof offered for Yang's pro-Japanese position. Could these assassinations have had some other motive? The author of this article believes so, based on two points yet to be considered in the existing research. The first has to do with the public careers and political ideas of the two victims. Studies have clearly shown the political ideas and actions of Zhang Xueliang from the time of the bombing death of Zhang Zuolin at the hands of a Japanese agent on 4 June 1928 to the hoisting of the Nationalist flag on 29 December of that year ; however, a similar analysis of Zhang's activities during that time has yet to be done, due to the a priori assumption that Zhang and Yang were political enemies. Consequently, we have no idea of Yang's policy stances or how they conflicted with Zhang's, other than the former's alleged pro-Japanese sentiment, leading to the conclusion that Yang's assassination was motivated by personal conflict between the two. This is why the author of the present article has felt the need to delve into the political ideas and actions of Yang and Chang Yinhuai. The author's second point focuses on the power structure of the Sandongxing 東三省 Regime and the political roles played in it by Zhang, Yang and Chang. Whenever conflict occurs in any political regime, clashes usually occur between factions, not individual politicians. In the case of the Sandongxing Regime, conflict not only occurred along generational lines (between the old timer and newcomer factions), but also geographically between the leading province in the triad, Fengtian, and the other two, Jilin and Heilongjiang. What remains unclear is where Zhang, Yang and Chang stood within the Regime's structure of conflict, which may be the key, to why the latter two were assassinated. One more factor that must be taken into consideration is the situation of the three countries bordering on the Sandongxing region : China, the Soviet Union and Japan. The research to date has tended to emphasize the actions of Japan in the framework of the historical background to its relationship to Manchuria. However, even if it can be proved that Yang was pro-Japanese, it is still important to identify his place in the Regime's structure and the Regime's relationship to its other two neighbors. Also, within the fluid international situation at that time, the Regime's structure was probably also in flux, one good example of which being Yang's assassination. With respect to China, it was being ruled by two central bodies, the government in Beijing ruling over Changcheng 長城 and all points south and the Nationalist government. However, these bodies did not exercise full control over the country in the same manner as the former Qing Dynasty or the later People's Republic. This is why the author deals with the "China factor" focussing not only on the two central ruling bodies, but also the, movements of the various warlord factions.

1 0 0 0 OA ラインラント共和国運動一九一八-一九一九とその背景

- 著者

- 尾崎 修治

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.104, no.10, pp.1756-1776,1838-, 1995-10-20 (Released:2017-11-30)

Die Rheinischen Loslosungsbestrebungen hatten zum Ziel, die rheinische Region von dem PreuBenstaat loszutrennen und so eine selbstandige Republik innerhalb des Deutschen Reiches zu grunden. Diese Bewegungen genossen vor allem in der politischen und verfassungsrechtlichen Ubergangszeit vom November 1918 bis Februar 1919 Unterstutzung durch Politiker und durch Teile der Bevolkerung im Rheinland. In diesem Artikel wird versucht, neben der Betrachtung der Entwicklung dieser Bestrebungen auch die Reaktionen der rheinischen Parteien und der zentralen Regierungen zu analysieren, um die Hintergrunde und die Tragweite der Loslosungsbestrebungen zu klaren. Unter den rheinischen Loslosungsbestrebungen dieser Zeit lassen sich zwei wichtige Richtungen erkennen. Zum einen der "Westdeutsche AusschuB", in dem sich Vertreter aller rheinischen Parteien zusammenschlossen, um eine mogliche Loslosung von PreuBen zu erortern. Diese Bewegung war durch die Furcht vor der Annexion durch Frankreich motiviert, und ihre Mitglieder waren sich daher darin einig, daB man das Konzept einer "westdeutschen Republik" nur dann in die Tat umsetzen durfe, wenn es die einzige Moglichkeit darstelle, um die Annexion durch Frankreich zu vermeiden. Diese Gefahr war jedoch niemals ernst geworden. Zum anderen ist die Richtung der Kolner Zentrumspartei zu nennen. Sie war im Gegensatz zum Westdeutschen AusschuB die aktivere treibende Kraft fur die sofortige Erfullung der Loslosung von PreuBen. Sie kritisierte die Unordnung in Berlin und die Machtlosigkeit der gegenwartigen Regierung und warnte vor der Gefahr der Annexion durch Frankreich. Diese Begrundung fuhrte zur Behauptung, daB das Rheinland sofort zur Selbsthilfe greifen musse. Die ungeduldigen Aktionen der Kolner Zentrumspartei wurden jedoch sowohl von den anderen rheinischen Parteien als auch von der Reichsund preuBischen Staatsregierung heftig kritisiert. Nicht zuletzt wegen dieser Gegenaktion wurde diese Bestrebung zuruckgestellt. Die Handlungen der Kolner Zentrumspartei wurden zwar kritisiert, doch die Motive, die hinter dem Konzept der Selbsttindigkeit von PreuBen steckten, wurden auch von den anderen rheinischen Parteien geteilt. Der Angriff der preuBischen Regierung auf die Rolle der Kirche stieB nicht nur auf den Widerstand des Zentrums, sondern auch auf den des ganzen rechten Lagers. Auch die Abneigung gegen die Revolution war im ganzen rechten und konservativen Lager zu beobachten. AuBerdem spielte das MiBtrauen gegen die zentralen Behorden eine wichtige Rolle. Es wurde dadurch geschurt, daB die Bevolkerung des Rheinlands in Berlin wenig Verstandnis fur ihre Bedurfnisse erkennen konnte und den Eindruck gewann, daB das besetzte Rheinland von der Regierung im Stich gelassen wurde. Daher lag die SchluBfolgerung nahe, daB die Rettung in der Selbsthilfe liege. Die Entstehung der rheinischen Loslosungsbestrebungen laBt sich daher nicht nur von der uberlieferten konfessionellen Besonderheit des katholischen Rheinlandes, sondern auch von den politischen und sozialen Bedingungen nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, vor allem der Revolution und der Besatzung, erklaren.

1 0 0 0 OA ポール・ズムトール著/鎌田博夫訳, 『世界の尺度-中世における空間の表象-』, 叢書・ウニベルシタス795, 法政大学出版局, 二〇〇六・一〇刊, 四六, 五〇一頁, 五六〇〇円

- 著者

- 小澤 実

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.116, no.10, pp.1690-1691, 2007-10-20 (Released:2017-12-01)

1 0 0 0 OA 平沼騏一郎内閣運動と海軍 : 一九三〇年代における政治的統合の模索と統帥権の強化

- 著者

- 手嶋 泰伸

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.122, no.9, pp.1507-1538, 2013-09-20 (Released:2017-12-01)

This article focuses on the relationship between the campaign to set up a cabinet under the premiership of Hiranuma Kiichiro and the Japanese Navy during the years of the Saito Makoto cabinet (25 May 1932-8 July 1934), in order to place this campaign within the context of the strengthening of the military supreme command system from the 1930's onward and clarify the influence of Hiranuma's plan upon the Navy, and the influence the resulting changes in the Navy exerted upon the campaign. In order to overcome a divided structure of governance, in particular control over military authorities, Hiranuma's campaign won faction leaders over to its side and utilized the authority of the imperial family. Therefore, Hiranuma's plan for controlling the military authorities did call for institutional reorganization, but rather depended on personal connections. Hiranuma made Fushiminomiya Hiroyasu chief of the Naval General Staff (NGS) with the cooperation of the Kantai (Fleet) Faction led by Admiral Kato Hiroharu, going as far as to reorganize the system by extending the authority of the NGS. However, the Kantai Faction lost its unifying position in the Navy when it was criticized for politicizing the NGS and politically utilizing the imperial family. Since Hiranuma's plan to control the military authorities involved winning over the leaders of the various factions, the fall of the Kantai Faction from power brought about the failure Hiranuma to act as the unifier of the divided governance system. Therefore, the campaign to form a Hiranuma Cabinet and the reinforcement of the supreme command in the navy developed under interrelationship of mutual influence. The collapse of the campaign after the Kantai Faction's attempt to utilize the authority of the imperial family resulted in the loss of its unifying position in the Navy means no less than the failure of Hiranuma's efforts to overcome the divided structure of governance by means of personal connections. Only the extension of NGS power-in other words, the strengthened independence of Supreme Command-remained after Kato's retreat and the collapse of the Hiranuma campaign.