1 0 0 0 現代日本語の表出語

- 著者

- バックハウス A. E.

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1983, no.83, pp.61-78, 1983

この小論の目的は, 現代日本語の語彙のうち, 「ぶつ」「みみっちい」 などのように, 語源的には和語でありながら, 一般の和語とは異なった特徴をもっている単語 (接辞も含む) を表出語 (expressives) と名づけ, その特徴を音韻, 表記, 意味, 文体の観点から分析し, 表出語が現代日本語の語彙の一つの語群を構成していることを主張することにある。ここでいう表出語は次のような特徴をもっている。<BR>(イ) 濁音で始まることがあり, 促音, 撥音, 拗音が現われやすい。<BR>(ロ) かな (原則として, ひらがな) で表記される。<BR>(ハ) 表出的, 感情的な意味をもつ。<BR>(ニ) 文体は話しことば的, 俗語的である。<BR>上記の特徴に注目しながら, 表出語をさらに中心的なものと, 周辺的なものとに区分けし, 代表的なものを出来るだけ多く例示してみた。

- 著者

- 簡 月真 真田 信治

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.140, pp.73-87, 2011-09

1 0 0 0 アフリカ人のコミュニケーション:―音・人・ビジュアル―

- 著者

- 梶 茂樹

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.142, pp.1-28, 2012

<p>サハラ以南のアフリカは,いわゆる無文字によって特徴づけられてきた。しかし無文字社会というのは,文字のある社会から文字を除いただけの社会なのだろうか。実際に現地で調査をしてみると,そうではなく,われわれの想像もつかないようなものがコミュニケーションの手段として機能していることがわかる。本稿では,私が現地で調査したもののうち,モンゴ族の諺による挨拶法と太鼓による長距離伝達法,テンボ族の人名によるメッセージ伝達法と結縄,そしてレガ族の紐に吊るした物による諺表現法を紹介し,無文字社会が如何に豊かな形式的伝達法を持ちコミュニケーションを行っているかを明らかにする。無文字社会では,言語表現が十分定形化せず,いわば散文的になるのではないかという一般的想像とは逆に,むしろ彼らのコミュニケーションは形式的であり韻文的である。それは文字がないことへの対応様式であり,共時的に,そして世代を通して伝達をより確かなものにする努力の表れと理解できるのである。</p>

1 0 0 0 韓国語の母音

- 著者

- 梅田 博之

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1994, no.106, pp.1-22, 1994

In the Seoul dialect, the pronunciation of vowels is different according to the age of speakers, and so the vowel system is also different. Generally speaking, speakers over sixty years of age pronounce the vowel e in two ways;one is [*] and the other is [*:].The former [*] corresponds to the Middle Korean vowel e in a low or high accent and the latter [*:] to e in a low-high accent.These two vowels appear almost complementary to each other, i.e. [*] appears as a short vowel and [*] appears as a long vowel in most cases.In spite of that, I think that each of these two vowels falls to a different phoneme for the following reasons: (1)each vowel of the Seoul dialect, except [*] and [*], has an opposition of quantity in the word-initial syllable, but the sound value of a long vowel is not different from the correspnding short vowel, (2) usually, [*] appears as a long vowel and [*] as a short vowel, but there are a few examples where [*] appears as a short vowel and we can also find a few examples where [*] appears as a long vowel.Therefore I consider [*] and [*] correspond to different phonemes.Consequently, there are nine vowel phonemes, /i, e, e, a, a, o, u, i, a/;and each vowel has the opposition of quantity in the word-initial syllable in older people's pronunciation.The vowel system of speakers over sixty years of age is shown as [2] of table 1.<br>In contrast to older speakers, younger people have a very simple vowel system which consists of seven vowels, /i, e, a, o, u, i, A/. Thus we find the very interesting situation that speakers of the Seoul dialect have different vowel systems depending on their age group.This is the result of diachronic changes that have occurred over the last few decades.<br>I investigated eighteen informants who were native to the mid-town area of Seoul in 1988 and 1989 to clarify how vowels changed according to the age of speakers.The types of vowel systems shown at table 1 were found in the investigation.<br>The vowel changes according to the speakers'age groups can be pictured as shown at the table 5.<br>[*:] of groups [1] and [2] phonemically changed into [i:] in groups [3] and [4] for basic words which they learned orally in their childhood, but in literary words they borrowed [*:] from the older people's pronunciation.<br>[*:] was brought into the pronunciation of group [5] by the influence of the written language, i.e.spelling pronunciation, as language education began to follow a regulated curriculum from primary school, and additionally due to the analogical change in the verb conjugation which first occurs in this group. In group [6], [i:] and [*:] joins [*:] due to the increasing influence of the written language and in addition by the analogical change in verb conjugation.<br>In group [7], long vowels lose length and accordingly [*:] changes into [A], losing lip-rounding.<br>With respect to the front vowel opposition, group [1] and [2] have a clear distinction in initial syllables, but in non-initial syllables it hasalready disappeared as a rule except in morpheme-boundary position. Roughly speaking, most informants of groups that follow group [3] show unstable distinction even in initial syllables.<br>Considering the above-mentioned vowel change, it can be summarized that the change goes on very gradually in each age group because it occurs under the linguistic influence of elderly groups to restrain from the change and also being receded by interference of the written language and analogical change.Thus we see the reason why the different vowel systems can exist synchronically in the same speech community.

1 0 0 0 長崎県口之津方言の形態音韻論

- 著者

- 南 不二男

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1966, no.49, pp.11-27, 1966

The purpose of this study is to analyze morphophonological “realization” processes of morphemes in the subject dialect, and to represent the results by ordered rules.<BR>Studied here is the dialect of Kuchinotsucho, Minamitakakigun, Nagasaki Prefecture.<BR>Two phases are assumed in the description: morphological phase, and phonological phase. Three units are assumed as constituent elements of the morpheme forms: morphophoneme (keitaionso), morphophone (keitaion), and phoneme (onso).<BR>In the morphological phase, morphophones are selceted from morphophonemes depending on morphological conditions. Morphological conditions are those total conditions in which are found the morphemes constituting the environment and the morphemes having the morphophoneme as a constituent element of their forms, and includes the tactical relation between the two morphemes. The following phenomena are treated in this phase: alternation of phonemes, e. g. t-d, s-h, e-u, e-i o-u, etc. and lengthening of vowels, e. g. toru (bird) qoori (dative form).<BR>In the phonological phase, phonemes are selected from morphophones depending on phonological conditions (the selection is conditioned by the phonemic system of the subject dialect). Phonological conditions are those total conditions in which are found the morphophones constituting the environment for the morphophone which happens to appear, and the tactical (phonotactic) relation between the two morphophones. The following phenomena are treated in this phase: alternation of phonemes as conditioned by the phonemic system, e. g. t-c, d-z etc.; assimilation of phonemes in the final morae of some words, e. g.-bu+bV→-Q+bV, -bu+mV→-N+mV etc.; dropping of consonants or semi-vowels, C1C2→C1, je, ji→e, i; shortening of long vowels, CVVN→CVN, CVVQ→CVQ etc.<BR>Each realization process is represented by a rule. Each rule consits of two parts: conditions, and result. Conditions are comprised of the logical product of the environmental element, tactical relation, and other conditions. e. g.(T<SUB>1</SUB><<M) ∩(T<SUB>1</SUB>=1) ∩(M=T<SUB>1</SUB>E<SUB>2</SUB>) ∩(x<SUB>1</SUB>prM) ∩(x<SUB>1</SUB>M=II):(T1→d)<BR>In general, the application of the rules of the morphological phase has precedent over the rules of the phonological phase.

1 0 0 0 國語動詞の一分頬

- 著者

- 金田一 春彦

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1950, no.15, pp.48-63, 1950

1 0 0 0 Karl Bühlerの言語三機能説

- 著者

- 神保 格

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1940, no.5, pp.1-13, 1940

1 0 0 0 ソシュールの言語理論について

- 著者

- 神保 格

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1939, no.1, pp.18-38, 1939

1 0 0 0 言語における杜會慣習

- 著者

- 神保 格

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1954, no.26, pp.1-15, 1954

Take those facts usually called Social Usage, ‘Custom, ’‘Convention, ’ etc. By analysing them, we find, among others, the following attributes:(<I>a</I>) Voluntary behaviour, (<I>b</I>) Mutual imitation, (<I>c</I>) Frequent repetition. We take up those facts which contain these attributes, and give them a provisional name ‘Social Usage’(or simply ‘Usage’). Corollaries to these are-1. Usage requires to be learned and memorized, to be ‘taught’ by environing persons. 2. Usage is fixed in abstract, as compared with each concrete instance of acts. 3. Number of persons who know and act a given Usage is limited, thus making up a ‘Usage-Community.’ cf.‘language (or linguistic) community.’ 4. Usage has a power outside of individuals, an existence that ‘transcends’ individuals.(A warning is here necessary, a warning against a confusion of (a) being outside of, transcending individuals and (b) being outside of, transcending all <I>human being</I>.) 5. Usage is subject to historical change.<BR>Each individual has a memory-idea of a usage. He can realize it in actual behaviour, but a voluntary act can be checked at will, or be replaced by other voluntary acts. We combine in daily life many voluntary acts in order to attain a remote end, (non-voluntary behaviours usually accompany them.) E. g. Catching a street-car (remote end). 1st. I rise up from my seat; 2nd. walk toward the door; 3rd. open the door; etc. etc. Each act is a voluntary one, containing in stself an end and a means (muscular movements). It is, so to speak, a ‘Unit’.

1 0 0 0 「擬態語」の名稱を疑ふ

- 著者

- 石黒 魯平

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1950, no.16, pp.29-36,160, 1950

Although words stand, theoretically speaking, for their referents merely in an indirect relation, and the further advanced the language the more indirect their relations grow, yet some words are in themselves highly suggestive of their referents. Hence are noticed the so-called imitative words, i. e., echoisms and onomatopceias. In those kinds of words our Japanese notably abounds, but besides those we exceptionally indulge in another kind of imitative words: we have a good many words of Mode-Analogy as I freely call them. They are sometliins like such English words as "pall mall", "pit-a-pat", or "zigzag".In closely examining about 700 imitative words of: these three kinds, I can not but complain of the prevailing misinterpretation of their real nature, and have come to take the liberty to suggest a reformed classification of them. They are to be assorted in these three kinds: Imitanturs (模写語), c. 170, Interpretanturs (註写語), c. 80, and Transferranturs (転写語), c. 450. The last are nothing than the so-called Mode-Analogy words. They are invented by, as it were, ql."translating" anything but acoustic phenomena into sounds. This third kind may be subdivided into A. of the Impression by Object and B of the Impression by Subject, each being viewed under two headings:<BR>A,(1) of Visual Impression, c. 180,(2) of General Impression, c. 180;<BR>to B (1) of Sensory & Visceral Impression? c. 40,(2) of the Reflection, of Mental State, c. 50.<BR>The corrected interpretation of the nature of Mode-Analogy words naturally rejects the prevailing name for them, "Gitai-go"(擬能語). The name "words imitating some states or appearances" as they use it is not comprehensive enough. <SUP>s</SUP>n>Moreover, zoologists have "long used the word" "Gitai", and that in the sense of imitative state or appearance not of "imitating other states or appearances" as linguistidians invertedly intend to designate by it Learning requires as little confusion vas possible in conception?

1 0 0 0 言語教授に於ける直観とその誤用

- 著者

- 石黒 魯平

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1942, no.10, pp.53-68, 1942

1 0 0 0 OA 九州方言におけるテ形音韻現象の崩壊について

- 著者

- 有元 光彦

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.158, pp.1-28, 2020 (Released:2021-02-16)

- 参考文献数

- 12

本稿の目的は,九州方言に広く起こるテ形音韻現象を対象とし,そこで分類される様々な方言タイプのバリエーション間に,どのような相関関係があるのかについて考察することにある。従来の研究で提案されていた「非テ形現象化」を分節音レベルで再検討し,それを「方言システムの崩壊」という新たな概念の中で位置づける。そして,テ形音韻現象の中で仮定されていたe消去ルール・e/i交替ルールの適用範囲が狭くなる方向への体系的な変化,特に非適用環境に関して「特殊から一般へ」の変化が起こっていることを明らかにする。また,地理的には,真性テ形現象方言が「五島列島→天草→熊本県南部」という順の崩壊プロセスをとるだけでなく,擬似テ形現象方言も「天草→熊本県北東部・大分県北西部」という崩壊プロセスをとる。異なる地域であっても,方言タイプにおいては同様の崩壊プロセスが起こっていることが明らかとなった。さらに,理論的には,崩壊プロセスが周圏性によって裏付けられることを示した。

1 0 0 0 言語島奈良県十津川方言の性格

- 著者

- 平山 輝男

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1979, no.76, pp.29-73, 1979

The Totsukawa dialect (TD) shares the accent of the Tokyo type, though TD is located in the area of the accent of the Keihan (Kyoto-Osaka) type. The accent of TD is derived originally from the accent of the Keihan type. Actually, the neighbouring dialects of Tanabe, Hongu, etc. exhibit the accent of the Keihan type clearly, namely they have more accent patterns than TD has.<BR>It can be concluded that the accent of TD has been transformed from the original type of acceet which had more patterns. This conclusion is supported by historical developments and the geographical distribution of dialects in the said area.<BR>As for other linguistic features such as segmental phonemes, morphology and vocabulary, TD is similar to the dialects of Tanabe, Hongu, etc.

1 0 0 0 プラーグ学派の言語観

- 著者

- 千野 栄一

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.61, pp.1-16, 1972-03

1 0 0 0 OA フォーラム アイヌ語研究の現状と問題点

- 著者

- 中川 裕 大谷 洋一

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1995, no.108, pp.115-135, 1995-11-30 (Released:2007-10-23)

- 著者

- 志波 彩子

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.158, pp.91-116, 2020 (Released:2021-02-16)

- 参考文献数

- 60

古代日本語のラレル構文体系と現代スペイン語の再帰接辞seによる中動態の体系は,外的動作主を介さない自然発生的変化の構文から外的動作主を必ず介する動詞にまで構文を拡張し,受身や可能を表す構文を持つ点では共通する。一方で,日本語のラレル構文は有情者に視点を置いた有情主語の受身を中心的に持つのに対し,スペイン語は中立視点で,事態実現の局面を捉える非情主語受身を中心に発達させている。その事態実現の非情主語受身の領域に,日本語は実現構文(自発・可能)を発達させている。また,日本語の可能は個別一回的な実現系状況可能であるのに対し,スペイン語のse中動態における可能は,潜在系の対象可能ないし場所・時間可能である。さらに,スペイン語の中動態も与格代名詞と組み合わさって「動作主に意志がないのに行為が発生する」という日本語の自発によく似た意味を表すが,中心的に用いられる動詞には両言語で違いがある。

1 0 0 0 OA 日本語の使役文の文法的な意味 ――「つかいだて」と「みちびき」――

- 著者

- 早津 恵美子

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.148, pp.143-174, 2015 (Released:2016-05-17)

- 参考文献数

- 29

使役文の文法的な意味については様々な分析がなされているが,広く知られているものとして「強制」と「許可」に分けるものがある。本稿ではこれとは異なる観点から「つかいだて(他者利用)」と「みちびき(他者誘導)」という意味を提案する。この捉え方は「強制:許可」という捉え方を否定するものではないが,原動詞の語彙的な意味(とくにカテゴリカルな意味)との関係がみとめられること,それぞれの使役文を特徴づけるいくつかの文法的な性質があること,この捉え方によって説明が可能となる文法現象がいくつかあること,という特徴がある。そのことを実例によって示し,この捉え方の意義と可能性を明らかにした。そして,「強制:許可」と「つかいだて:みちびき」との関係について,両者はそれぞれ使役事態の《先行局面/原因局面》と《後続局面/結果局面》に注目したものと位置づけ得ることを提案した*。

- 著者

- 伊藤 創

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.154, pp.153-175, 2018

<p>一方から他方へ働きかけがなされる事態を描写する際,英語母語話者は働きかけ手(agent)を主語に立てる傾向が日本語母語話者のそれより強い。本研究では,この描き方の型の違いが両者の事態の捉え方の型の違いに根ざしているのかどうかを検証するため,働きかけに関わる事態について,その「次」に起こった事態を想像してもらい,いずれの参与者を主語として描くかを比較した。次の事態を描く際には,当該の事態でより焦点をあてて捉えている参与者について描くのが自然と考えられるからである。結果は,ほぼ全ての画像で英語母語話者のほうが日本語母語話者よりagentを主語に立てる割合が高かった。このことから,1)日英語母語話者の事態の描き方の型の違いは,両者の事態の捉え方の型の違いに根ざしており,2)その違いは,英語母語話者は行為連鎖/力動関係において力の源である参与者に,日本語母語話者は共感度の高い参与者により際立ちを感じやすいという違いであることが強く示唆される。</p>

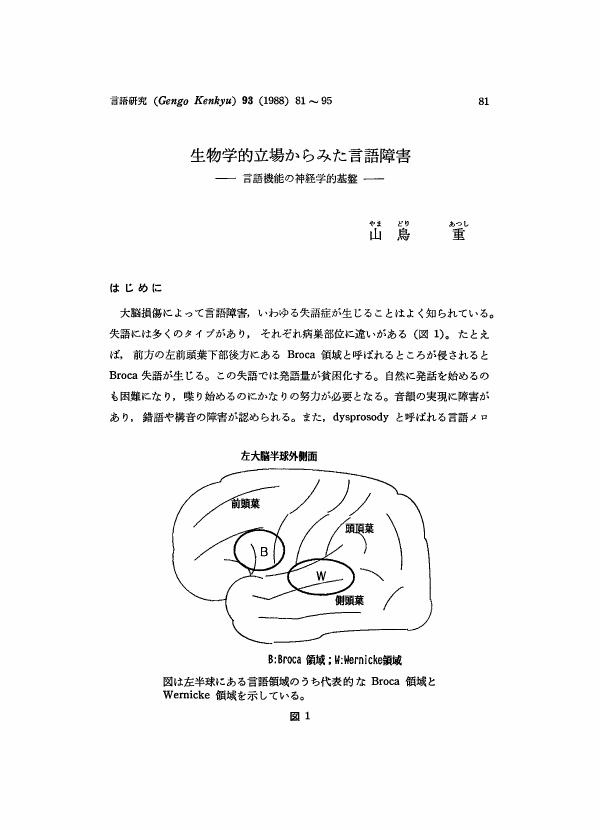

1 0 0 0 OA 生物学的立場からみた言語障害 言語機能の神経学的基盤

- 著者

- 山鳥 重

- 出版者

- 日本言語学会

- 雑誌

- 言語研究 (ISSN:00243914)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1988, no.93, pp.81-95, 1988-03-25 (Released:2010-11-26)

- 参考文献数

- 15