14 0 0 0 OA 明治期における尖閣諸島への日本人の進出と古賀辰四郎

- 著者

- 平岡 昭利

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.57, no.5, pp.503-518, 2005-10-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 92

- 被引用文献数

- 1 1

The Senkaku Islands are made up of five uninhabited islands scattered about 170km north of the Yaeyama Islands of Okinawa Prefecture. In recent years the territorial claims on these islands made by China and Taiwan have increased since it was found that under that area there is a lot of petroleum and natural gas. No one has ever sufficiently examined why Japanese people in the Meiji Era started going to these islands made only of rocks. This study discusses the Japanese advance into and the development of the Senkaku Islands. The following is its summary;The territorial possession of the uninhabited Senkaku Islands started with the exploration by the Okinawa Prefectural Government in 1885, and the exploration report says that a large flock of albatross was found there. In the 1890's, the Japanese advance into the Senkaku Islands was accelerated in order to get the albatross plumage and the great green turban. In those days the Okinawa Prefectural Government had to plead with the Meiji Central Government again and again to put national landmarks on the islands because it was not clear whether the islands were actually Japanese or Chinese territory. Finally in 1894, the Meiji Government permitted to put the national landmarks. In 1895 the Senkaku Islands were placed under the jurisdiction of Okinawa Prefecture. In the same year, Tatsushiro Koga, who was a powerful and wealthy shellfish merchant, asked the Meiji Government to lease Kuba Island for the purpose of catching albatross because of the rapid decrease of the great green turban. His business changed from shellfish to albatross. In 1896, the Government not only leased Kuba Island to him but also granted him the lease of another four Senkaku Islands for 30 years.In 1897 Koga started his business in the Senkaku Islands, but albatross, his main resource of business, decreased devastatingly in only three years. Therefore, he diversified his business into stuffed birds, bonito fishing, guano, and phosphate rocks and managed to make an immense profit. But his business didn't last long because he mismanaged the natural resources on the islands. Koga Village, founded in Uotsuri Island with a huge investment of money, disappeared in about 30 years and around 1937 the Senkaku Islands again became uninhabited with no change since then.

14 0 0 0 OA 中年シングル男性を疎外する場所

- 著者

- 村田 陽平

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.52, no.6, pp.533-551, 2000-12-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 80

- 被引用文献数

- 4 5

Over the decades since the 1970s, feminist geography has challenged the exclusion of women from the production of geographical knowledge. With the emergence of feminist geography, gender perspectives have attracted considerable attention. However, men who feel alienated by changing gender roles have not received much attention. The purpose of this article is to elucidate the empirical situation of the masculinity of geographical knowledge by highlighting the major characteristics of alienated middle-aged single men in contemporary Japan.In the introductory section, an overview and the significance of feminist geography are discussed. This is followed by a discussion of the importance of men's studies within gender research in geography. The development of men's studies has enabled an interrogation of masculinity from varied angles.The second section is devoted to an explanation of the interview method employed in the article and its limitations. The informants are ten single men, aged 35-64. Their narratives are quoted as evidence of their alienation.The third section interprets the concrete places within which middle-aged single men feel alienated. The specific contents of these places of alienation are presented as follows:1. In rural areas, where they do not play an important role within patriarchy, they are not regarded as 'full-fledged' men.2. At the workplace, where they are unable to participate in male bonding which is a feature of homosocial workspaces.3. At home, where the lack of women results in their homes being labelled as 'dirty', as men are considered to lack the ability to do housework.4. In contemporary gendered urban spaces, where despite an image of these spaces allowing diversity, middle-aged single men feel suppressed.The evidence from the research points to the above four factors being the main considerations underlying the alienation of single and middle-aged men.Based upon the discussion of the preceding sections, the fourth section interprets the meanings of space and place from the standpoint of men who feel alienated, with reference to feminist geography. Firstly, it is noted that place in humanistic geography, which has been criticized by feminist geography as having a masculinist bias, alienates middle-aged single men, as well as women. Moreover, feminist geography points out that the notion of space in Marxist geography is also gendered. This paper draws attention to the fact that gendered space does not privilege all men, but just those men who meet certain conditions of masculinity.The final section discusses the conclusion reached, that hegemonic masculinity in geographical knowledge oppresses not only women, but also men. Therefore, it follows that we need to elucidate differences among men.

13 0 0 0 OA ロシア人以前の西シベリア開拓

- 著者

- 三上 正利

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.9, no.5, pp.323-339,401, 1957-12-30 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 73

In Western Siberia it was in the late Palaeolithic Age that men came to liver for the first time (Cf. Fig. 1). They enlarged their dwelling. area as far as_ the lower Ob River in the Neolithic Age (Cf. Fig. 2). The first farming of Western Siberia was begun in the southern part of it at the Andronovskaya epoch (1700-1200 B.C.). The northenmost bounds of agriculture in the end of the Bronze Age were along the line of Kurgan, Petropavlovsk and Omsk. In other words, they were in the southern part of the forest steppe zone. In the part of the Minusinsk Basin, irrigation-farming was begun at the Tagarskaya epoch (700-100 B.C.). About the fifth century, they started to till the fields with plough under the influence of China. S.V. Kiselev states that hack-tilling with irrigation played the main role in the rise of the Türk people(_??__??_)in the Altay in the sixth century and that plough-tilling with irrigation came to have an important meaning in the rise of the Kyrgys people(_??__??__??_)in the upper Yenisey River in the tenth century. The agriculture in Southern Siberia, which had developed comparatively highly in the ancient time, fell into decay in the latter period.When the Russian people began colonizing in the end of the sixteenth century, the northernmost bounds of agriculture by the native peoples had moved up to the north as far as the line of Tobolsk, Tomsk and Krasnoyarsk. In other words, they were in the south of the forest zone. Only the Tatars of the Siberian khanate were tilling with plough, and the rest peoples were tilling with hack. In general, agriculture was mere the supplementary means of industry to hunting, fishing and stock farming. There were some peoples who didn't engage in agriculture. From the oldest times, Western Siberia had been the mixed area of the race of the mongoloid type and the race of the europeoid type. There were Mongoloid peoples in the north and Europeoid peoples in the south. In the Minusinsk Basin, however, mongolonization came to have a remarkable meaning at the Tashtykskaya epoch (1c. B.C-4c. A.D.). It means the process of Turkicization in the fields of both language and civilization, in which the peoples called the Tatars by Russians were formed, in the Altay and the middle and upper parts of the Yenisey River.

13 0 0 0 OA 「寄せ場」釜ケ崎と「野宿者」

- 著者

- 丹羽 弘一

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.44, no.5, pp.545-564, 1992-10-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 67

- 被引用文献数

- 1 4

This article seeks to explain the circumstances of homeless people in Osaka City and their temporal change using the concept of the social space in an urban area. The special concern here is Kamagasaki District, a typical and nationally well-known yoseba (the space served as a catchment place of day laborers for jobs regarded as relatively unskilled). Such places generally have a large number of cheap lodging houses (doyagai) for them. The homeless people in Japan, mostly single man, were called formerly runpen or furosha, and currently are known as nojukusha. They correspond to day laborers in a substantive sense.Kamagasaki is a commonly-used place name of the neighborhood, located in the northeastern part of Nishinari-ward, Osaka City, and its extent is almost identical to that of Airin-chiku (Airin District), as is has usually been referred to by the administrative authorities, police and mass media. There is a huge day labor market centered on Airin Multi-purpose Center in this area and it is generally said that the district has more than twenty thousand day laborers, about two hundred cheap lodging houses and numerous eating houses, resulting in a distinctive landscape segregated from surrounding areas.In the second section, previous research of yoseba is reviewd. This district has been studied as a disorganized area mainly by social pathologists in the existing literature of social science. But it mirrors a negative and passive understanding of this social space in urban area. The author here, putting emphasis on the social structural context, would like to identify a certain social space focused on the district. On this occation the actual situation concerned with the homeless is a very good indicator of the social space.The third section is devoted to a historical explanation. In the period immediately after World War II, Osaka City's governmental measures toward the homeless was to settle disorder due to the influx of sufferers and returnees in and around Osaka Station. Nevertheless, as the district served as the place for single male day laborers during the period of fast economic growth in the 1960s, the homeless within the city tended to be accounted for primarily by Kamagasaki's day-laborers. Then, the measures were developed in the Airin regime (Airin taisei) which was established in the beginning of the 1970's, motivated by the‘riots’and still continues. The survey of occupational careers conducted in 1988 indicates that, the numbers of homeless persons rise occur in the season or months when jobs are unavailable, whereas they become laborers in the remainder.Specific attributes are discussed in the fourth section. According to the records of the Thursday Night Patrol Party within the Kamagasaki Christian Society, there is a general tendency to seasonal size change in incidence of the homeless: they expand from April to summer and then contract. Such change is due to the job offering variation concerned with the labor force through the Nishinari Labor and Welfare Center as well as climatic condition such as temparature. Moreover, the records suggests that this change has been less remarkable within the district, while now obvious outside it. Also worthy-of-note is that, as the number of the homeless as a whole tends to decrease, the inside-the-district proportion has been lower.In the 1988 investigation, the homeless persons are grouped into the following three length types: the long type (more than one year), the short type (less than one year), and the cyclic type, which implies repeatedly homeless and non-homeless conditions seasonally over the past years. Furthermore, such types are cross tabulated with income source and reason for becoming homeless. With regard to the source, many of the long and short types work as junk dealer (yoseya), while most of the other type are day laborers.

- 著者

- 齋藤 駿介

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.74, no.1, pp.1-26, 2022 (Released:2022-04-19)

- 参考文献数

- 28

本稿では,近代仙台における法定都市計画の展開と市域拡張の関係を,周辺町村の動向に着目しながら明らかにする。仙台都市計画の主眼は周辺町村の市街化・工業化に置かれ,その展開に呼応して市域拡張が3次にわたって実施された。仙台市主導の第1次市域拡張は先行して指定された都市計画区域と同域を対象としており,直近の法定都市計画に必要な領域を取り込むという目的が明確であった。一方,第2・3次市域拡張は,隣接村からの強い要望の下で実施された。この背景には,法定都市計画の進展が周辺地域に都市計画・市域拡張の恩恵を意識させ,それと同時に周辺地域内での競争意識を駆り立てたことがあり,仙台では先行する市域拡張が次なる市域拡張を惹起させていた。さらに,都市計画は一貫して市域拡張の必要性を主張する根拠として引用されたが,合併の必要性が差し迫ってはいなかった第2・3次市域拡張ではその役割がより強調された。こうして法定都市計画と市域拡張の実施による「大仙台」建設への期待は高まり続けたが,実際には都市計画事業の進捗は大幅に遅延していた。以上の考察から,近代仙台における法定都市計画は実際の都市空間を改変する技術としての意義以上に将来的な近代都市「大仙台」建設のビジョンを示す意義が重視されており,市域拡張は「大仙台」の展開領域を具体的に提示することで遅延しがちな法定都市計画を補完する役割を果たしていたと考えられる。

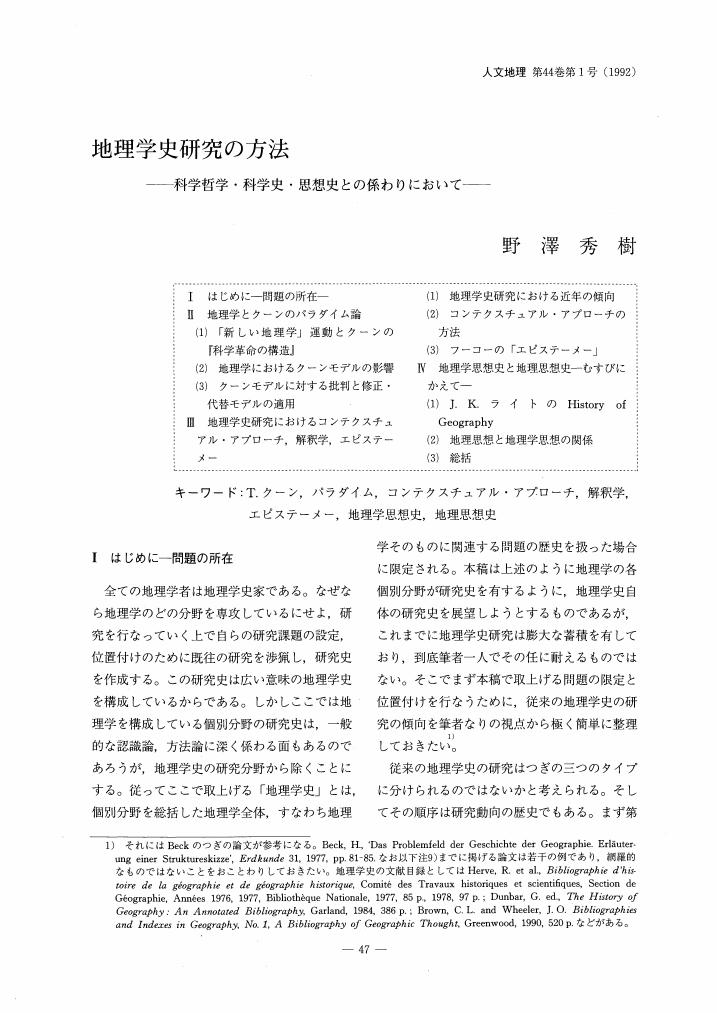

12 0 0 0 OA 地理学史研究の方法

- 著者

- 野澤 秀樹

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.44, no.1, pp.47-67, 1992-02-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 145

- 被引用文献数

- 4 1

12 0 0 0 OA 保倉川舊河道の中世開發水田

- 著者

- 籠瀬 良明

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2, no.3, pp.36-47,96, 1950-07-30 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 18

In the plain of Takada can be traced an old watercourse of the Hokura about five kilometers in length. What characterize this old watercourse are free meandering and natural banks, running on both sides of it and higher than the level by one meter or two with fields and hamlets on them. A long succession of fine paddy-fields stretehes on this old course of the river, which were brought under cultivation in middle ages. (Especially, it is the case with the lower course of the river.)In the article two of those examples, Matsuhashi and Funatsu in the village of Honda are dealt.[The author made a lecture on other such examples, Honda-Enokii and Katatsu, at the autumnal meeting of Association of Japanese Geographers last year, and explained why the region should be supposed to have been cultivated in Middle Ages, also explaining its characteristics. The details are to be mentioned in next number.]

11 0 0 0 OA 和人地・蝦夷地の境界とその変遷

- 著者

- エドモンズ リチャード

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.33, no.3, pp.193-209, 1981-06-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 74

- 被引用文献数

- 1

Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, Japan's northern island, Hokkaido, was divided into a Wajin-Japanese settlement exclave, called Wajinchi or Wajinland, and an area in which only Ainu were allowed to reside permanently, known as Ezochi. This paper looks at changes in the location of the boundary and in the function of guardhouses located near it as one way to analyze Tokugawa frontier policy. Sources include diaries of travelers, government documents, old maps, and sketches.Results show that the Wajinchi expanded in five stages. From the thirteenth to the mid-sixteenth century, Wajin-Japanese settlement remained in a punctiform pattern with forts spaced along the extreme southern coast of the Oshima Peninsula. This initial stage is characterized by a lack of unity among Wajin and relative strength of the Ainu.Next, an accord reached around 1550 between the strongest Wajin-Japanese leader and two Ainu chieftains delimited a conterminous zone on the southwestern tip of the Oshima Peninsula. This second phase suggest the unification of Hokkaido's Wajin was well underway.The Matsumae clan formed in the early seventeenth century, expanded the exclave, demarcated the boundary with poles, and established guardhouses. During the following two centuries, these efforts to partition the Wajin-Japanese and Ainu continued. It is of special note that the distance between Matsumae castle and the eastern and western boundaries was roughly equivalent.A major policy transformation occurred at the beginning of the nineteenth century when the Tokugawa government took over control of Ezochi, installed a magistrate in Hakodate, and extended the eastern portion of the Wajinchi. The concern of the Tokugawa government in the affairs of Ezochi was apparent since the new eastern guardhouse was located on the Ezochi side of the boundary, a condition. which had never previously existed.In the mid-nineteenth century, the Wajinchi was enlarged again. However, the absence of boundary guardhouses along with the lack of contiguity marked this as a transitional stage prior to the opening of the whole island for colonization in 1869.These Wajinchi expansions can be conceived of as concentric zones. The second and third stages surround Matsumae castle while the fourth and fifth have double foci, Hakodate and Matsumae, and generally encircle Hakodate. The lack of guardhouses in the second and fifth stages illustrates their transitional character in contrast to the third and fourth stages of Matsumae and subsequent Tokugawa direct control.

11 0 0 0 OA 愛知県常滑市における「ギャンブル空間」の形成

- 著者

- 寄藤 晶子

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.57, no.2, pp.131-152, 2005-04-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 53

- 被引用文献数

- 3

In this paper, the author argues that gambling businesses managed by public authorities face issues regarding monopolization, regulation of space and socio-spatial exclusion.Since the end of the 19th century, informal private gambling has been strictly outlawed in Japan, while both the national and local governments have resorted to investing in the gambling business to secure revenue. At present, with the exception of lotteries, 120 gambling facilities such as keiba (horse race), keirin (bicycle race on a short track), autorace (motorcycle race on a short track), and kyotei (motorboat race on a square pond) are offered by 21 prefectures and 443 municipalities. These are called "public gambling".In his book The Production of Space, Henri Lefevre notes that non-productive expenses are made according to the neocapitalist's interest. Therefore, the author refers to the three elements that constitute space according to Lefevre: spatial practices, representations of space and space of representations. The author conducted field work in and around the motorboat gambling facility operated in Tokoname City, Aichi Prefecture, and the highlighted the "gambling space" using Lefevre's scheme mentioned above.From 1997-2000, the author interviewed: Tokoname motorboat officers, residents from the areas (sinkai-cho) around the motorboat facility, police officers, members of the "koie-sinkai crime prevention association", a security guard and ticket sales women employed at the motorboat office, shop managers in and around the motorboat facility, and the motorboat gambling fans. The author also conducted participant observation studies of more than 400 motorboat gambling fans. The author's findings are as follows:Firstly, while the public authority, the Tokoname motorboat office, adopts several measures to draw visitors to the motorboat facility and thus ensure income, this practice includes spatial separation, i.e., separating the Tokoname motorboat gambling fans from the public. This is partly because the nature of gambling itself threatens social order, therefore, the public authorities control and enclose gambling fans. These practices of exclusion are observed in their spatial practices.Secondly, shops and restaurants are located on the route taken by visitors from the Tokoname railway station to the motorboat facility. These shops and restaurants sell alcohol, low-priced light meals and magazines or newspapers regarding gambling. Fans regularly take the route from the Tokoname railway station to the motorboat facility and purchase these goods from these shops. Loitering fans and torn blank tickets visibly distinguish the "gambling space" from the rest of the city. Japanese public gambling fans are largely men over 60 years of age. However, in Tokoname motorboat facility, 60-70% of motorboat gambling fans are men, who are 60 years and over. Therefore, the "gambling space" is occupied by middle and old-aged men is littered with blank tickets.Thirdly, measures adopted by the local community, the "koie-sinkai crime prevention association", neighborhood residents and the police to regulate the behavior of visitors' create negative representations of Tokoname motorboat gambling facility and its fans. In 1970, as the number of visitors increased, a few residents living around the motorboat facility founded a crime prevention association in order to put a burglar alarm to their house. At this time, the Tokoname motorboat office began sending presents, such as handkerchiefs, rice, pans and soaps as compensation to residents. The activities of "koie-sinkai crime prevention association" provided subsidies by Tokoname City, although they are not strictly monitored. They unfairly claimed and represented the undesirable behavior of visitors in order to protect their interests.

10 0 0 0 OA 平城京における胞衣埋納場所の選地

- 著者

- 山近 久美子

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.62, no.3, pp.231-250, 2010 (Released:2018-01-19)

- 参考文献数

- 99

This study examines the ideas of ancient people about places for placenta rituals in Heijo-kyo, the 8th-century capital of Japan. The placenta is the material that comes out of a woman’s body after she gives birth to a baby, which is necessary to nourish and protect the baby in utero. Traditionally, the treatment of the placenta has been associated with the health and future of the baby, so there are many forms of related ceremonies around the world.In Japan, placenta rituals took different forms in different periods. In many modern instances, the placenta was wrapped with paper or cloth and put in a pot, then buried underground in an auspicious direction. The pot contained, if the baby was a boy, a brush or an ink stick with his placenta. If the baby was a girl, there was a thread or a needle with her placenta.Archaeologists have cited placenta rituals in folklore for their interpretations of pottery-buried remains. Many archaeologists have believed pottery was ritually buried around the front door of houses since in folklore, the placenta was frequently put in a pot and buried under the entrance of a house. But placentas were actually buried in various places apart from the front door; for example, in the shade, on mountains, by the roadside, in estates, under the floor, and in lavatories.The oldest attested pottery-buried remains are found at the capital, Heijo-kyo. It is difficult to determine the purposes of burying earthenware during the Nara period. Yet two major purposes are for ground-purification ceremonies and for placenta rituals. So this paper first attempted to classify them by the kinds and the contents of the ritually buried pottery. The typical pottery used for placenta rituals is Sue ware jars called “Sueki tsubo A”, resembling a medicine pot that was associated with Yakushi or the Buddha of healing. The typical contents of the pottery are ink sticks, brushes and pieces of cloth.The sites where pottery-buried remains were unearthed are large in size and near the Heijo Palace. This fact suggests that placenta ceremonies were carried out by government officials of the Heijo-kyo capital. And the sites of rituals were not always at entrances, but in many cases around the houses. According to ancient Chinese medical books, burying the placenta in the shade was taboo. But in modern folklore of Japan, the shade was often chosen as the place for burying the placenta, and many placentas were buried under the floors of houses.In this respect, the sites where pottery-buried remains were unearthed in Heijo-kyo differ from those of placenta rituals as described in modern folklore. We came to the conclusion that though in Heijo-kyo they had their own idea about the placenta burial site, the rituals were typically performed by government officials on the basis of ancient Chinese medical books.

10 0 0 0 OA 日本における宗教地理学の展開

- 著者

- 松井 圭介

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.45, no.5, pp.515-533, 1993-10-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 127

- 被引用文献数

- 4 3

Geography of religion aims to clarify the relationships between the environment and religious phenomena. In Japan, this discipline has four major fields of researchThe first field is that of the relationships between the natural environment and religion. The emphasis in this field, however, is on the influence of the environment upon religion. Whereas many scholars study how climate and topography change the formation of religious beliefs, there is almost no study of the influence of religion upon the natural environment. In order to fill this lack, it is necessary, for instance, to clarify the role of religion in environmental protection.Secondly, geographers of religion study how religion influences social structures, organizations, and landscapes in local areas. They mainly examine the urban structure and its transformation within religious cities with regard to the dominant religion. There are also some studies about the significance of religion for the formation of new cities. The relationships of the religious orientation to the local structure of cities and villages, however, has not been thoroughly clarified yet.Thirdly, pilgrimage forms another major field of research in the geography of religion. Most studies so far, however, remain preliminary, showing the routes of pilgrimage without reconstructing networks among sacred places and their surroundings. Moreover, the contemporary meaning of pilgrimage is not studied enough, though people today still carry out pilgrimages fervently.Lastly, geographers of religion try to clarify the structure of space which is created by the sacred, through examining the distribution and propagation of religion. One of the major studies in this field is that of sphere of religion.This geography of religion as the study of relationships between the environment and religion has two indispensable approaches, for the space created through these relationships has two aspects; empirical and symbolic. On the one hand, religion has power to organize local communities and this power generates the structure of space which is grasped empirically. On the other hand, religion supports human existence through offering a cosmology. This cosmology appears in the structure of space symbolically. Geography of religion should understand the religious structure of space throughly by adopting both positivistic and symbolic approaches.

10 0 0 0 OA 輪島市海士町の漁民集団

- 著者

- 祖田 亮次

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.48, no.2, pp.168-181, 1996-04-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 38

- 被引用文献数

- 1

The fishing group of Amamachi community, at the tip of the Noto Peninsula jutting out into the Japan Sea, is very distinctive in terms of life style. It has thus attracted many previous studies on this group in various disciplines. Most of them, however, have tended to demonstrate its uniqueness by introducing its uncommon customs. Nevertheless, such a conventional view should be modified now: this group, I think, is typical of kaimin (maritime people), one of the major marginal groups, whose importance has been r6ather neglected so far due to an influential and far-reaching point of view focused on rice cultivation.In the third section, the primary purpose to see them within the whole context of Japanese society in the right perspective was pursued. To do so, their situation was investigated in reference to kyakumin (major marginal people with autonomy) or kaimin with their own histories different from paddy-cultivating people. Unlike most kyakumin/kaimin groups, which have been weakened, dissolved or extinguished because of their failure in coping with new situations brought by changes over time, the Amamachi community has lasted well until now. Its sustainability deserves careful attention.Amamachi's fishing people are considered to be descendants of fishing people of Kanegasaki District located in the northern part of Kyushu. Since their arrival at the Noto Peninsula, they had been engaed in diving fishing under the protection of the Kaga Clan (Maeda Territory) until the end of the Edo Period (1603-1867). They had been conscious of their distinct characteristics and confirmed the difference between their own and surrounding societies by stressing their relation with the Kaga Clan and by remembering their own historical origin. Such an attitude was effective in keeping the autonomy of the group against the dominance of shumin (main people) engaged in paddy cultivation. In this sense, the Amamachi community indicated a prominent characteristic corresponding to that of kyakumin.On the other hand, another characteristic of theirs as kaimin is found in the following attitudes: wider mobility to seek better fishing grounds and acquire new trading areas, aggressive fishing methods based on high technical skills, and indifference to agriculture in general.In the fourth section, the second aim of this paper to substantiate the sustainability of the community was explored chiefly by tracing changing processes of systems and customs of their society. In particular, I devoted attention to the two periods when the community confronted crises of existence: the time of the second half of the nineteenth century, when the modern age began in Japan, and the high economic growth period in the mid-twentieth century. Their reponses for surviving can be summarized as follows:As for the second half of the nineteenth century, because of the collapse of the Bakufu-system, the relation between the Kaga Clan and this community was annulled. This implied that they would lose the exchange route for marine products and agricultural crops. Fortunately, however, a loose stratification occurred in this period, resulting in an establishment of the oyakata-kokata (patron-client) relation. While oyakata newly came to be in charge of the exchange instead of the Kaga Clan, kokata could peddle their extra products individually-this was called nadamadari (peddling trip)-. This suggests that newly emerged oyakata had a certain power, but nadamawari and other community controls restrained an excessive stratification.With respect to the high economic growth period, the wide diffusion of powerboats improved fishing productivity and accelerated the monetary economy. These changes caused a dissolution of oyakata-kokata relation and a decline of nadamawari.

10 0 0 0 OA 空間スケールの再構築と不均等発展の新しいグローバルな地理

- 著者

- スミス・ ネィール

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.52, no.1, pp.51-66, 2000-02-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 35

- 被引用文献数

- 2 6

1980年代と1990年代のグローバル化に関する広く行きわたった認識は、資本蓄積の進行に地理的空間がますます関わらなくなっているという考えを助長してきた。多くの公式的な見解とは反して、グローバル化は金融資本の国際化よりも製造資本の国際化に刺激を受けている。グローバル化のもとでは、はるかにより包括的な過程が生じている-それは徹底的な地理的スケールの再構築である。本稿は、資本蓄積が、経済的な状況については国民国家の相対的後退を伴いつつ、グローバル-ローカル関係がますます決定的になる新たな段階に突入していることを論じる。このことにより、グローバルな資本の中核に多くのアジアとラテンアメリカの経済が状況に応じて統合される一方でアフリカと世界中の縁辺化された人々がますます追い払われる、地理的不均等発展の新しいパターンがあらわれている。

9 0 0 0 OA 1920年代の樺太地域開発における中国人労働者雇用政策

- 著者

- 阿部 康久

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.53, no.2, pp.99-122, 2001-04-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 109

- 被引用文献数

- 3 2

The purpose of this article is to clarify employment policies and to provide some background regarding Chinese workers developing a colony in Sakhalin during the 1920s, paying attention to the whole labor policy including those directed toward Japanese and Korean workers.The data used in this analysis were the confidential documents produced by the Karafuto government and the local newspaper, 'Karafuto nichinichi shinbun', which were obtained from the diplomatic record office of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Hakodate city library and the National Diet Library. The results of the paper can be summarized as follows.The employment of Chinese workers was caused by the need to develop the colony and the severe shortage of labor in Sakhalin. Namely, after world war I, in Sakhalin, a paper manufacturing industry developed, but labor to construct plants and infrastructure was in short supply. Therefore, the Karafuto government considered the use of Chinese workers.When the Karafuto government recruited Chinese workers, they assigned a quota to companies and contractors which expected to employ them and the authorities forced these employers to abide by this rule. Furthermore, the authorities prepared a detailed outline to manage Chinese workers and forced employers to abide by these laws. The main aspects of this outline were as follows: (1) to employ Chinese as seasonal workers in order to prevent them from permanent residence; (2) to force Chinese workers from having as little contact as possible with Japanese people, and (3) to gather Chinese workers from the same region or village in order to link friends and relatives which would serve as a deterrent to escape.Thus, Chinese workers were employed as seasonal workers from 1923 to 1927. They were gathered from around the province of Shandong in Northern China and were employed in various undertakings, such as railroad construction, plant construction, mining, and so on. Among these undertakings, the largest was the construction work of the Karafuto east coastal railroad leading from Otiai to Siritori. During construction, about 1, 500 Chinese workers were employed.However, some local residents started movements against the use of Chinese workers on this project. Merchants in Toyohara, Maoka, and Tomarioru districts were especially opposed to the use of Chinese workers, on the grounds that they would not contribute to the local economy due to their tendency to save money and send wage remittances to China.In addition, labor disputes were often raised by Chinese workers regarding their employment. The main reasons for these disputes were poor working conditions, such as a low wage level, nonpayment of wages, contract discrepancies and charges paid to middlemen for their passage to Sakhalin.In those days, the wage levels of Japanese workers who were employed in the construction and labor sectors were 2.0 to 3.5 yen a day, and those of Korean workers, who were colonized under Japan, were 1.8 to 2.5 yen a day. However, those of Chinese workers were about 1 yen a day at first, but their wages were later raised by 0.2 to 0.3 yen. Furthermore, from their wages employers deducted food expenses, charges, and so on, thus reducing their net wage to only 0.6 to 0.7 yen per day.In spite of these movements against Chinese workers and the labor disputes raised by them, the Karafuto government allowed companies and contractors to employ Chinese workers for five years in order to attempt to halt the increasing population of Korean workers. According to the results of the national census taken in 1930, the Korean population in Sakhalin was 8, 301, which accounted for 2.81 percent of its total population. Compared with the Korean population in 1920, which were 934, the number increased rapidly in 1930.

9 0 0 0 OA ポストモダン人文地理学とモダニズム的「都市へのまなざし」

- 著者

- 加藤 政洋

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.51, no.2, pp.164-182, 1999-04-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 130

- 被引用文献数

- 3 1

There has begun to develop a burgeoning new problematic in recent works in human geography addressing the debate around postmodernism and the city. David Harvey's The Condition of Postmodernity (1989) and The Urban Experience (1989), and Edward Soja's Postmodern Geographies (1989) are major works on this theme. While their contribution to 'postmodern geography' is now widely accepted, they have been criticized by some feminist geographers such as Massey (1991) and Deutsche (1991) for their suppression of difference, their failure to be aware of masculinity and their lack of recognition of feminist theories of representation in their works. There is one other matter which is important in these criticisms. As Deutsche and Gregory (1994) have acutely pointed out, Harvey and Soja read the city as a distant silhouette and both accord a particular privilege to this distant view.The purpose of the present paper is to outline a series of debates, as mentioned above, around ways of seeing the city in contemporary urban studies in general, and to undertake a critical assessment of Harvey's voyeurism in his 'Introduction' to The Urban Experience and Soja's solar Eye (looking down like a God) in 'an imaginative cruise' in particular. In addition to this purpose, I am going to suggest two directions for a postmodern geographical critique of the modernist gaze on the urban condition-the politics of representation and the politics of scale.The second section of the paper explains the change in Harvey's attitude towards the city. We can observe this change in the transfiguration of the leading figure from a 'restless analyst' (in Consciousness and the Urban Experience) to 'the voyeur' (in The Urban Experience). Harvey, as the restless analyst, places an exaggerated importance on wandering the streets, playing 'flaneur', watching people, eavesdropping on conversations and reading local newspapers. In short, he learns more about the city and its urban condition by engaging in microgeographies of everyday life and pursuing a view from the city streets. As the voyeur, however, he makes a point of ascending to a high point and looking down upon the intricate landscape of streets, built environment and human activitv. In the 'Introduction' to The Urban Experience, Harvey so obviously prefers the view from above as a voyeuristic way of seeing the city that homogenizes street life, urban life and everyday life in a desire for legibility/readability. Thus, the privileging of the high viewpoint is his particular method of conceptualizing 'the city as a whole'. For Harvey as the voyeur, therefore, the position of restless analyst in the street 'cannot help acquiring new meaning'. This goes to his modernist sensibility.In Postmodern Geographies, Soja introduces his most exciting essay on Los Angeles as an attempt to evoke a 'spiraling tour' around the city that he made with Frederic Jameson and Henri Lefebvre. This essay is not a mere field report, but he tries to recapture their travels as ';an imaginative cruise'! The third section of the paper points out that his 'imaginative cruise' is conducted from many vantage-points and so Soja's position on urban studies implies a Foucaldian panoptic gaze. For example, although Soja declares that 'only from the advantageous outlook of the center can the surveillant eye see everyone collectively, disembedded but interconnected', he climbs the high rise City Hall building and looks down on the landscape of downtown. The view from this site is especially impressive to Soja as one of surveillance.What I try to show in sections 2 and 3 is that there is a great similarity between Harvey and Soja in their ways of seeing the city.

9 0 0 0 OA 江戸時代綿作の分布と立地に関する歴史地理学的考察

- 著者

- 浮田 典良

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.7, no.4, pp.266-283,330, 1955-10-30 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 57

- 被引用文献数

- 2 1

Although the cotton production in Japan rapidly fell into decay after the middle of the Meiji period under the pressure of imported raw cotton, it once flourished remarkably during the Edo era and the first half of the Meiji period as one of the most advanced fields of agriculture in Japan.The writer tried to trace back and see the geographical distribution of the cotton production in Japan in the Edo era, and further, made research for its location in the regions of dense distribution. As a result of the research, the following points were made plain:1, Raw cotton was cultivated chiefly on the sandy upland-field, especially old sand bar and reclaimed land, on the delta of big rivers.2. On the other hand, in the Kinai (Osaka, Kyoto, Nara and their neighbourhood), the district which advanced in civilization from old times, raw cotton was cultivated, as well as rice plants, in a paddy-field in alternate years.3. These are the two types of location for the cotton production in the Edo era. The latter was started from comparatively early years, but the part it played dwindled toward the closing years of the Edo era, while the former has gradually come to play a dominant part. That is to say the location for cotton production shifted from the paddy-field to the sandy upland-field. The reasons for this were (1) sandy soil of the upland-field was suitable for the cotton production, (2) no other suitable crops could not be cultivated on the sandy soil, and (3) the upland-field being a new land, taxes on it were rather low.

9 0 0 0 OA 平和記念都市ヒロシマと被爆建造物の論争―原爆ドームの位相に着目して―

- 著者

- 阿部 亮吾

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.58, no.2, pp.197-213, 2006 (Released:2018-01-06)

- 参考文献数

- 88

Hiroshima is very famous because it was the first city in the history of the world that was hit by an atomic bomb. The purpose of this paper is to explore the controversy over the conservation or demolition of the buildings damaged by the atomic bomb (the buildings A-bombed) in Hiroshima. There are two important agents concerned with this controversy. One is the local administration of Hiroshima City, which wants to remove these buildings. The other comprises a number of groups who want to conserve them. Through two significant controversies over the buildings A-bombed since the 1970s, I first examined the claims of the two conflicting sides and made it clear that these controversies are, in fact, spatial conflicts over “landscapes of the atomic bomb”.1. The local administration has a spatial orientation that tries to contain the A-bombed memory and history in Hiroshima into a limited landscape of the atomic bomb, including the Atomic Bomb Dome as a “Symbol of Peace’’ and the peace memorial park around it. Atomic Bomb Dome was decided in 1966 to conserve in perpetuity, and, in 1996, it was registered on the UNESCO World Heritage list.2. Conservation group advocates have insisted that landscapes of the atomic bomb must be established all over Hiroshima through an expansion of the example of the Atomic Bomb Dome.I explain that the current controversies concerning the buildings A-bombed in Hiroshima are spatial conflicts between the local administration and conservation groups, and I point out that the Atomic Bomb Dome plays an important role in these controversies.Second, I explored the historical moment when the administration’s orientation was formed by examining the period of recovery (1945-1952) from Second World War damage. I paid attention to important city plans for recovery in this period, and analysed two urban concepts which city planners were concerned with at that time. As a result, I revealed this point: 3. Two concepts were fitst, a “peace city’’ concept which contributed to the establishment of the bill for the construction of a peace commemorating city and second, an urban concept about modernization which formed the basis of the city planning for recovery. And both of them produced the peace memorial park around the epicenter. Then the Atomic Bomb Dome was positioned as an important component of the park and defined as the “the only one’’ building A-bombed in Hiroshima. This definition played a vital role in the fate of the other buildings which were A-bombed, because it meant that all of these, except for the Dome, would be excluded from both the processes of construction of a peace commemorating city and a modern city. I think this definition was the historical moment that led to the local administration’s current orientation.Now, in face of the visible disappearance of other buildings except for the Atomic Bomb Dome, there has been an increase in the number of different voices on rethinking how Hiroshima should be in the future. I conclude that our historical-geographical imaginations of the history and memory affected by the atomic bomb are essential for rethinking the future of Hiroshima.

9 0 0 0 OA 空間構造の人文主義的解読法

- 著者

- 山野 正彦

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.31, no.1, pp.46-68, 1979-02-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 114

- 被引用文献数

- 18 7

8 0 0 0 OA 近代における空間の編成と四国遍路の変容

- 著者

- 森 正人

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.54, no.6, pp.535-556, 2002-12-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 101

- 被引用文献数

- 2 3

This paper discusses the changing spatiality and movement modes of the 'Henro' pilgrimage on Shikoku Island from 1920-1930. The pilgrimage is one of principal topics in the geography of religion, and geographers have analysed its spatial structure using historical, quantitative and humanistic approaches. For those researching the spatiality of the pilgrimage, it is necessary to clarify the contested processes by which spatiality was produced and the manner in which discourses concerned with modes of movement were produced in order to control the flow of pilgrims. Though pilgrims mainly traveled on foot for religious training, there were no statements concerning the pilgrimage route in guidebooks published at Edo era.Since the modern Japanese government created a transport system to create homogeneous space in Japan, several transport systems-train, bus and ship-were available in Shikoku until the middle of 1930s. For pilgrims who used these transport systems, movement patterns during the Henro pilgrimage became diversified. However, since the end of the Taisho era, 'the intellectual class' who had hardly previously participated, became interested in the Henro pilgrimage. As a result of this change, the Henro pilgrimage became involved in domestic tourism as alternative form of tourism at the end of the 1920s, and pilgrims using the new transport system and taking casual pleasure in were referred to as 'Modern Henro'.On the other hand, in 1929, 'Henro-Dogyokai', which aimed to organize pilgrims and provide several activities concerned with the Henro pilgrimage, was founded at Tokyo. Its goal was to enlighten people along national policy and to criticize the Modern Henro because they regarded its style as religiously regressive. Through providing information about the Henro pilgrimage in their monthly journal Henro and their activities, they emphasised the authentic style or way of the Henro pilgrimage, and at the same time they emphasized that pilgrims should journey on foot.In short, from the end of 1920s to the middle of 1930s, while Japanese tourism or 'Modern Henro' represented the space of the Henro pilgrimage as tourist space, 'Henro-Dogyokai' represented it as religious training space. However, both agents reconstituted the network in the space of the Henro pilgrimage; indeed the space of the Henro pilgrimage was a contested one in this period. Of course, traditional pilgrims-those who had not been admitted to live their village community and could do nothing but carry on the pilgrimage with begging -also existed. In this context, the reconstituted Henro pilgrimage was appropriated within Japanese fascist policy through its articulation with hiking in the middle of 1930s, and Modern Henro' and 'Henro-Dogyokai' were placed within national ideology. The Japanese government coerced people into walking to make proper bodies and to pray for victory in World War II. In this policy, adopting various modes of movement in pilgrimage was unacceptable since pilgrims were compelled to walk. However, despite this policy, some pilgrims refused to comply and some of them preferred to use transportation.

8 0 0 0 OA 近江国伊香郡における式内社と氏族

- 著者

- 佐野 静代

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.45, no.1, pp.83-97, 1993-02-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 73