45 0 0 0 OA KJ法と啓発的地誌への夢

- 著者

- 川喜田 二郎

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.25, no.5, pp.493-522, 1973-10-29 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 15

- 被引用文献数

- 1 3

Geography is a “field science” in the sense that it needs field work. In spite of it, the methodology on field work is not yet satisfactory through various branches of science including geography. Present article is a rough sketch and comments on the personal history of my inquiry into the methodology of field work, especially in the fields of geography and ethnology. In particular, a method of idea generation named KJ Method which was generated by me was explained in detail.For the purpose of recording field data, I devised a form of data card (abbreviated as DC; cf. Fig. 1). In order to classify a file of DC, I tried to adopt the classification table of HRAF (Human Relations Area Files). Soon, however, I understood that classification only was much unsatisfactory for a field worker who sought for true integration of data. Quite different from classification and analysis, another unknown methodology for the purpose of “Facts speak for themselves” must exist.In around 1951, I obtained a first hint for this purpose. And my work “Ethno-Geographical Observations on the Nepal Himalaya” (in Peoples of Nepal Himalaya, ed. by H. Kihara) became the first output along this new method of data processing. Later on, this methodology was greatly improved by myself and named KJ-M. in 1965 by various men. It was a nickname in origin. The first book systematically written on this methodology “Hassôhô” (Abduction) was published in 1967. (cf. References.) This method was welcomed very much, firstly in the fields of company management, business and engineering and gradually in the field of education and science.In the basic KJ-M, there are four essential steps: a) label making, b) label grouping, c) chart making, d) explanation. Label making is to record one concept on a label usually in the form of sentence. (Rarely in the form of any picture.) Surrounding a theme, as rich variety of labels as possible are collected. Label grouping is attained through the repetition of the steps of making teams of labels and title making. Through this process, a number of labels are organized, not by the classification based on some pre-conceived ideas but according to the appeals of original labels. In the step of chart making, these organized labels are spreaded spacially on a sheet according to the recognition of natural relationship among the titles or labels. At last a multi-layered complex relationship between the labels is presented in a chart. Then the last step “explanation” is applied to this chart, i.e. explanatory story making connecting all labels in writings or by verbal explanation.Using the basic KJ-M. repeatedly, we can challenge highly complex problem solvings. A full process of the basic KJ-M. was named “a round”. Multi-round application of this method is called the Cumulative KJ Method (C-KJ). When a C-KJ is applied along the course of problem solving shown in the W-shaped chart (Cf. Fig. 3 and Fig. 7), this method is most fruitful.Using the steps of field work→recording DC→using KJ-M. and C-KJ, chaotic field data can be organized heuristically. The course of data processing is clear and open to anyone who wants to know it. Plenty of hints, hypotheses and generalization arise on the way and in conclusions. These suggestions are not harmful because of subjective judgement but welcomed because of stimuli to readers, as the grounds and processes which bore these suggestions are offered to them frankly. The readers may agree with the author or oppose him. In both cases, both parties will receive desirable stimuli through the dialogue. Thus a basic recognition that data are never facts and the means of observation and data processing intervene between the two leads to the truly scientific and charming geography or ethnography.

37 0 0 0 OA 明治初年の都市分布

- 著者

- 森川 洋

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.14, no.5, pp.377-395, 1962-10-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 31

- 被引用文献数

- 2 2

The purpose of this article is to classify the characteristics of the distribution of Japanese towns before the industrial revolution. To qualify such towns, the author uses “Kyomhseihyo” (1880), the national statistics on population and products, and limits as town the settlements with over 2, 000 persons, but some fishing villages may be exceptionally contained among them.The author thinks that the distribution of those towns is analogous to that “alten Kulturländer” called by G. Schwarz, which roughly speaking is related to the density of rural population (Fig. 1.) There was a dense net of towns with much urban populatin in coastal and basin regions (densely populated), where there were also large towns like Tokyo (725, 000), Osaka (363, 000), Kyoto (136, 000), Nagoya (117, 000), Kanazawa (108, 000) etc. (Fig. 2 and 3). Of course, the agglomeration of towns and urban population in those days were not in so large scale as in the present day.But the distribution of towns in those days can not be explained by population density only. The ratio of urban population per Kuni, regional division in those days (Fig. 4) and the hierarchical structure of towns were related more closely to scale of regional centres than to economic richness of the areas. For example, the large regional centre Toitori (36, 000) and some small towns (2-3, 000) lay in Inaba-Kuni, so that the ratio of urban population per Kuni was raised (exclusively) by the urban population of Tottori.Most of such regional contres were castle towns in feudal age, and their scale was in proportion to that of territories of “Daimyoes”, feudal lords. The origin of small towns was mosily market towns, coaching towns, and port-towns, which had grown in proportion to regional economic development.Therefore, the distribution of towns in early Meiji-era was related to hitstorical conditions in feudal age everywhere.

31 0 0 0 OA 選挙地理学の近年の研究動向

- 著者

- 高木 彰彦

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.38, no.1, pp.26-40, 1986-02-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 103

- 被引用文献数

- 3

28 0 0 0 OA 村落空間の分類体系とその統合的検討

- 著者

- 今里 悟之

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.51, no.5, pp.433-456, 1999-10-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 183

- 被引用文献数

- 1

Over the last few decades, theories of the spatial structure of Japanese villages have been the subject of controversy in human geography, folklore, cultural anthropology, history and architecture. The author identifies an important unresolved question concerning these theories. Although many scholars have profoundly discussed each of the categories of space such as land use zones, folk-taxonomy, 'place', social space, and symbolic space, the interrelationships among these categories and the synthesis of them have not been sufficiently examined.With this in mind, this article discusses each of the categories of space for a case study area, an agricultural and forestry village-Hagikura-in Central Japan, to reveal the interrelationships among all spatial categories by introducing a semiotic theory. The author examines the historical changes of space since the mid-Edo era, when Hagikura was settled. To pursue these aims, various methods and materials are used: interviews, landscape observation, participant observation, the analysis of land ledgers, cadastral maps, tax ledgers, local topographies, historical documents and geographical statistics.Hagikura was a shinden settlement which stands on a river terrace near Lake Suwa in Nagano Prefecture, and is now a mixed-settlement in which newcomers from Shimosuwa Town have settled since the era of rapid growth in the Japanese economy. The subsistence farming economy of Hagikura is based on paddy, mulberry and vegetables, sericulture and forestry. In addition, people have been engaged in filature in the Meiji era, agar production in the Taisyo era and dairy farming and flower cultivation in the 1960s. Recently, almost all farmers have become factory or office workers, commuting to the towns along Lake Suwa.The findings of this article can be summarised as follows. The folk-taxonomy of space, which is deduced by an investigation of place names and folk categories of landscape, is composed of five levels: land use zone, subdivision of the zone, koaza (small place name), block name, and strip name. In the residential area, there is another classification system of social space composed of four levels: dual organization, mutual aid organization for funerals, neighborhood group, and household. In each land use zone, the shrine which guards the people working in each zone is located showing the center of meaning. As the center of the total area, the shrine of the settlement is located at the cardinal point of two axes of folk orientations which structure the village territory in concentric circles. These orientations are prescribed by the zofu-tokusui topography of fung-shui tought, whose rear is a hill and front is a river. This spatial structure with these land use zones and folk orientations is found similarly in homesteads and fields owned by each household. The boundaries of each land use zone and village social space are demarcated by objects such as stone statues and isolated trees, and through varied ritual behaviors. The social space of the village community which corresponds to the village territory is divided into nested boxes according to the social group system. All of the boundaries of the village are folk, social, mental, or symbolical, and the outer boundary of the forestry zone is, at the same time, a geographical or administrative one.The social structure of the village social space is composed of three groups-'natives', oldcomers and newcomers. The natives who settled in the Edo era and consist of nine kinship groups were former landowners or independent farmers. The oldcomers who settled in the Meiji era as filature or farming workers were tenants of native landowners in the Taisyo and early Showa eras. The newcomers are factory or office workers who have settled in new housing estates since the rapid growth of the Japanese economy. The main native families occupied the cultivated fields near the residential area.

27 0 0 0 OA 関東低地における散村の成立と微地形

- 著者

- 岡本 兼佳

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.7, no.3, pp.182-194,248, 1955-08-30 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 8

- 被引用文献数

- 1

For the approach to the reasons of dwelling dispersion, it is fundamentally necessary that the settled order should be made clear by tracing back to the early stage of the reclamation and throughout the progress. From this point, the writer researched into the dispersed settlement on the deltaic plain between two rivers, the Edo and the Furutone, Kanto lowland. The following conclusions were reached:1. The pioners located their homes apart from one another and rarely adjoined besides the line villages. This dispersion of the pioneers resulted from selecting the highest island-like embankment in order to secure their farmsteads from flood waters. When the embankment was too lower to avoid flood, the dweller still more raised up the ground artificially.2. The community in this region is chiefly organized with the relation of head and branch, so the reasons for the dispersed dwelling can be attainable through the branching of the families. Distinguishing the families in the same lineage and ranging them in settled order, and then drawing them on the map, the settlement growth and especially where the branch families select as the house sites are made clear. These distribution types are classified as follows; (A) scattering type of branch families, (B) adjoining type of a branch family to its head family, (C) adjoining type of a branch family to another.3. Classifying the own-fields of the dispersed branch families by distribution, two types are recognized; (a) concentrated type around the house site or stretched type in front of his house site, and (b) remote type. The latter is subdivided into three types; (1) scattered type, (2) distant and yet concentrated type, (3) two groups type in front and at a distance. Each of these types is exemplified in Fig. 3, 4 and 5. When the dwelling is located in the center of the own-fields the most convenience of farming is given. In this region, however, some of the dispersed branch families have the fields in type of remoteness and scattering, because they can not get at will the favorable elevated house site everywhere.4. The adjoining type of a branch family to its head family has also two distribution types of the own-fields; (a) stretched type in front of both families in their way, (b) remote type in the branch family's fields. The latter is classified into the same three types as the case of the dispersed branch families. The examples are given in Fig. 6 and 7.5. The adjoining type of a branch family to another makes the distribution types of the own-fields as follows; (a) contrated type adjacent to the house site in each family or stretched type in front of both families in their way, and (b) remote type in the later settler. This dwelling type and the distribution types of fields are based on taking the elevated dry lots for the house sites.6. Subsequently some farmers removed from other places and they also settled in the types of adjoining and scattering. In that case, the settlers mostly looked for the elevated dry lots and consequently the same dwelling types were shaped.7. The ruined sites were scarcely resettled and were usually changed to the fields and even the lots leaved to the overgrowth with trees and grasses turned out. The inhabitants seem to have evaded such ruined sites psychologically.8. In Tab. 3 the elevated island-like lots are classified by size and are compared with the existence of dwelling. Inspecting this, the greater the lot area becomes, the more dweller it stands, conversely, the smaller lots are entirely used as the fields. By every size of the elevated lots, averaging the area of the house sites possessing on each, the home site areas increase in proportion to the elevated lot areas. This proves that the locating of the dwelling is adapted for the elevated lots. The changes of the landuse follow even the artificial changes,

26 0 0 0 OA インフルエンザの時・空間的流行モデル

- 著者

- 中谷 友樹

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.46, no.3, pp.254-273, 1994-06-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 90

- 被引用文献数

- 1 1

A mathematical model is built for influenza or other similar disease epidemics in a multi-region setting. The model is an extended type of chain-binomial model applied to a large population (Cliff et al., 1981), taking into account interregional infection by interregional contacts of people. If the magnitude of the contact is presented by simple distance-decay spatial interaction or the most primitive gravity model, a conventional gravity-type epidemic model (Murray and Cliff, 1977; Thomas, 1988) is deduced.Given the number of infectives and susceptibles, the chain-binomial model predicts the number of infectives in the next period with binomial probability distribution. Available data are, however, weekly cases per reporting clinic in each prefecture reported by the surveillance project, characterized by continuous variation; the data could be a surrogate index for rates of infection. The author modified the model to use rates of infectives and susceptibles, and used a normal approximation of binomial distribution. With the maximum-likelihood method, this model can be calibrated. The specification of the model is as follows:Li(Yi, t=0, …, Yi, t=T|β°i, δi)=Πt1/√2πVar[Yi, t+1]·exp{-1/2Var[Yi, t+1](Yi, t+1-E[Yi, t+1])}, E[Yi, t+1]=β°i/MiXi, tΣjmijYj, t, Var[Yi, t+1]=β°i/MiXi, tΣjmijYj, t(1-β°i/MiΣjmijYj, t), Xi, t=δi-Σis=0Yi, s, where Mi=Σjmij; Li denotes the likelihood of the model for region i; Xi, t denotes the estimated rate of susceptibles in region i at week t; Yi, t denotes the reported rate of infectives in region i at time t; mij denotes the size of interregional contact with the people in regions j for the people in region i; β°i denotes the infection parameter in region i; δi denotes the parameter concerned with the rate of initial susceptibles in region i.The model posits that the average number of people who come into contact with a susceptible in prefecture i is a constant, and that the average rate of infectives of the people is ΣjmijYj, t/Mi. The probability of a susceptible in region i infected at time t is, therefore, β°iΣjmijYj, t/Mi.This model was applied to a weekly incidence of influenza in each prefecture, from the 41st week, 1988, to the 15th week, 1989, Japan, letting the size of interregional passenger flow Tij correspond to mij as follows: mij=Tij+Tji (i≠j), mii=Tii.Goodness-of-fits (Table 1) of one-week-ahead forecasts were almost satisfactory except for prefectures whose epidemic curves were bi-modal (e.g., Hokkaido) or whose transition speed between epidemic breakout and peak was too high (e.g., Yamagata). The latter might be explained by a cluster of group infection (e.g., school classes) in an earlier phase of the epidemic (see Fig. 4).

24 0 0 0 OA 石川県南加賀地方出身者の業種特化と同郷団体の変容

- 著者

- 宮崎 良美

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.50, no.4, pp.396-412, 1998-08-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 61

24 0 0 0 OA 大和棟の分布とその系譜

- 著者

- 早瀬 哲恒

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.10, no.4, pp.251-267,314, 1958-10-30 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 76

- 被引用文献数

- 1

The ‘yamato-mune’, or ‘takahei’, is a type of roofing popular among private houses. What characterizes it is the way that the thatched gable roof has its gable-walls plastered with wall mud and then covered with tiles. The aim of this thesis is to classify its varied forms and examine the distribution as well as the route of distribution of those various forms in order to throw light on the process of development of the ‘yamato-mune’.Several varieties are found in the ‘yamato-mune’ roofing:I. the fundamental type; ‘takahei’, ‘naka-takahei’, ‘hizumi-takahei’;II. the tiled-roof type; ‘hakomune’, ‘daimune’, ‘okimune’;III. the intermediate type; ‘ryogawa-danchigai’, ‘kata-takahei’;IV. the ‘Koshiore’ type;V. the Kawachi type;VI. the cryptmeria bark- or board-roof type;VII. the zinc-roof type;IIX. other varieties.The ‘yamato-mune’ is mainly used in the Yamato Basin, but the range of its distribution extends west to Kawachi, Settsu, and Izumi, east to the Iga Basin, south to the basin of the River Yoshino (or Kinokawa), and north as far as that part of southern, Yamashiro along the River Kizu. It is also found at a few specific places outside this general range. Distrtbution of several of its varieties is as follows:the fundamental type: to be found in the Yamato Basin;the Kawachi type: Kawachi, Settsu, and Izumi;the ‘hizumi-takahei’ Kawachi: southern and middle Kawachi, Kii;the ‘daimune’ tiled-roof type: north Kawachi;the ‘higashi-sanchu’ tiled-roof type: the Yamato Plateau;the ‘uda-sanchu’ cryptmeria bark-or board-roof type: Oku-uda districts.The ‘yamato-mune’ roofs seem to be distributed along routes of traffic or along rounts of migration of the carpenters. As we move along the principal rountes of traffic from the Yamato Basin to the surrounding districts, we find the fundamental type gradually changed to or replaced by other types. For instance:the fundamental type—the intermediate type—another type of roofing, principally the ‘irimoya’ roofing, which originally belonged to those districts surrounding the Yamato Basin;the fundamental type—the ‘hakomune’—the ‘daimune’;—the Kawachi type;—the ‘daimune’ or the ‘koshiore’;—the ‘higashi—sanchu’—the Iga type (the tiled-roof ‘yosemune’); etc.The fundamental type found in the Yamato Basin is obviously the original ‘yamato-mune’, and the genealogy of the fundamental type is to be further questioned. At present the writer of this thesis tends to think that its prototype would be either the ‘takahei’ roof or the ‘naka-takahei’ roof. This, however, will have to be treated in another thesis.

24 0 0 0 OA 都市内部中心地区の階層と形態指標の対応関係

- 著者

- 西村 孝彦

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.31, no.6, pp.524-538, 1979-12-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 39

- 被引用文献数

- 3 1

19 0 0 0 OA 江戸時代におけるコレラ病の流行

- 著者

- 菊池 万雄

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.30, no.5, pp.447-461, 1978-10-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 30

It is said that in the Edo Era cholera prevailed in Bunsei 5 (1822), Ansei 5 (1858) and Bunkyu 2 (1862). In considering the actual substance of each epidemic from the number of the deaths recorded in the necrologies of temples, the following became clear.1) The epidemic in Bunsei 5 was the first big incident of this in Japan. As for the invasion route of cholera to our country, although there are several opinions, it can be established that invasion came through Nagasaki.Cholera prevailed in south-west Japan, especially in the San'in and San'yo areas, but it did not reach north-east Japan or Edo.2) The Ansei epidemic started from Nagasaki, and became quite widespread all over the country in Ansei 5 and 6, spreading as far as Edo and Mutsu.The Ansei 5 epidemic was the first one in Edo and it was particularly serious but as regards the country as a whole, there seem to have been more places where the epidemic broke out in Ansei 6 rather than Ansei 5.Because there was so much recorded concerning the epidemic in Edo, it was wrongly thought to be the biggest epidemic of cholera in modern age in our country.3) Cholera also prevailed on a great scale over the whole country in Bunkyu 2. To consider this as a continuation of the epidemic in the Ansei period is wrong, for it is established fact that in the first year of Bunkyu, matters were completely back to normal and that the epidemic in the second year of Bunkyu came in from Nagasaki and spread from there.It is possible to say that the cholera epidemic in Bunkyu 2 was substantially the worst in the Edo Era, because it was widespread throughout the country and the number of victims was so great.As the record of deaths in the necrologies show pronounced peaks coinciding with the sudden infection of cholera and high death rate, and as the peaks occur at different times depending on the district, it is easy to trace the infection route of cholera.Furthermore, based on various old records of public government offices, villages and temples, we can endorse the following points concerning the prevalence of cholera at that time.* That the invasion route of cholera started in Nagasaki.* That the theory of the big three epidemics in Bunsei, Ansei and Bunkyu stands, rather than the theory of the big two in Bunsei and Ansei.* That the Ansei 5 epidemic occurred in Edo only, and that as regards the whole country the theory that the worst epidemic was in Bunkyu 2 stands rather than the theory that it was in Ansei 5.

16 0 0 0 OA 中国山東省における餃子食の意味と地域的特質

- 著者

- 于 亜

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.57, no.4, pp.396-413, 2005-08-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 33

- 被引用文献数

- 2 2

Every traditional society has its own particular regional food culture. The dumplings examined in this article are one example. In northern China, the dumpling has played an important role in food culture, not only materially but also spiritually. Dumplings even have meaning as ceremonial foods, and they form one of the chief elements of traditional food culture. Due to the liberal reform policies carried out in the 1980s, the Chinese economy has developed remarkably, and daily life, especially the food culture of the Chinese people, has changed radically. The aim of this paper is to examine the changing nature of the traditional food culture by focusing on the dumpling, and also to examine the changing meaning and function of the dumpling itself.The region discussed in this paper is Shandong in the lower Yellow River valley. The present state of dumpling food culture was investigated in seven districts within this region. In each district I distributed questionnaires, interviewed local people, and consulted historical records concerning food culture.The Shandong region is the birthplace of the dumpling and we can trace the historical development of it by using local documents. People consume dumplings in various settings, not only in daily life, but on formal occasions as well. The latter category includes annual celebrations and ceremonial events such as weddings, funerals, ancestor-worship rituals, and coming-of-age ceremonies. People still recognize dumplings as a vital dish. Moreover, on formal occasions, the opportunity for consumption, the reason for consumption, the place of consumption, and the group preparing the dumplings differs from place to place. Thus, the dumpling in Shandong is a daily food staple made out of wheat, and, at the same time, is a part of the local food culture that is valued socially and ritually.Since every local area has its own natural environment and historical and social background, types of dumplings differ by locality. However, people's respect for the dumpling is universal. By observing variations in the form of dumplings and by interviewing cooks, it becomes clear that knowledge about dumplings-their different types, forms, and functions-is a sort of folk wisdom that has spread widely.

15 0 0 0 OA 漁村における家屋の機能変化とその要因

- 著者

- 河原 典史

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.42, no.2, pp.168-181, 1990-04-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 42

- 被引用文献数

- 5

The regional character of different places can berecognized through living styles and their changes in rural houses. In this study, the author examined functional changes and their factors in rural houses according to the changes in fishing, taking rural houses in fishery villages which have been neglected as an example. As a case study, the author took up funaya settlements in Ineura, in which many kinds of functions are mixed.It was in the Taisho Era that the living functions of funaya which had functions for fishing, such as dry-docking a boat, keeping fishery tools, drying fishing nets and so on, began to come into existence. And it was after World War II that these living functions remarkably expanded.The forms of funaya have greatly changed from a simple two-storied house to a regular two-storied house, because the living space has expanded to the upper stories of funaya since the war ended.The following factors can be given as the reasons for which funaya are equipped with living functions:1. the economic factor: prosperity of fishing in 1950, 1951 and in 1970∼1975.2. the physical factor: linear villages which have little space for housing land.3. a social factor: the rise of nuclear families.Non-fishing families which have a large main house don't need funaya so few of these funaya are equipped with living functions. Furthermore, since about 1965, funaya have had a surplus of living space, so some houses are often found to be changed into minshuku (guest houses).At the present time, the place for dry-docking a boat on the first floor of funaya is classifiied into 4 types: A, B, C and D (see Fig. 8). The main reason is that fiberglass-reinforced-plastic (F.R.P.) boats were introduced in 1969 and the weaving industry spread in 1961.A type: This type doesn't show changes of form. Despite being equipped with dry-docking functions, these are hardly used.B type: Though this type shows changes in form, it still preserves its function for dry-docking boats.C type: This is the type in which formal change is the same as the functional one when the function for dry-docking boats disappeared because of the introduction of F.R.P. boats.D type: This is the type in which the function for dry-docking of boats has disappeared and the forms have changed a great deal, owing to protection of weaving machines and commercial goods.

15 0 0 0 OA フェニキア人のアフリカ大陸周航

- 著者

- 織田 武雄

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.3, no.5-6, pp.152-162,A15, 1952-01-15 (Released:2009-04-30)

- 参考文献数

- 45

Either to affirm or to deny the circumnavigation of Africa by Phoenicians there are not sufficient data, because Herodotus' description of it is brief. It may be wise to conclude, like Bunbry, “it is not proven”.However, when the oceanic currents and wind are taken into consideration, it is understood that the least geographic obstacles will be met if the sailing around of Africa is started from the east seacoást of the continent. Also, while Polynesians got to almost all islands in the Pacific by means of their primitive canoes, Phoenicians had possessed better vessels and navigation than Polynesians.If indirect evidence such as above mentioned is taken into accounts, the circumnavigation of Africa by Phoenicians may be considered “gar nicht unwahrscheinlich, ” as remarked by Humboldt.

14 0 0 0 OA 明治期における尖閣諸島への日本人の進出と古賀辰四郎

- 著者

- 平岡 昭利

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.57, no.5, pp.503-518, 2005-10-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 92

- 被引用文献数

- 1 1

The Senkaku Islands are made up of five uninhabited islands scattered about 170km north of the Yaeyama Islands of Okinawa Prefecture. In recent years the territorial claims on these islands made by China and Taiwan have increased since it was found that under that area there is a lot of petroleum and natural gas. No one has ever sufficiently examined why Japanese people in the Meiji Era started going to these islands made only of rocks. This study discusses the Japanese advance into and the development of the Senkaku Islands. The following is its summary;The territorial possession of the uninhabited Senkaku Islands started with the exploration by the Okinawa Prefectural Government in 1885, and the exploration report says that a large flock of albatross was found there. In the 1890's, the Japanese advance into the Senkaku Islands was accelerated in order to get the albatross plumage and the great green turban. In those days the Okinawa Prefectural Government had to plead with the Meiji Central Government again and again to put national landmarks on the islands because it was not clear whether the islands were actually Japanese or Chinese territory. Finally in 1894, the Meiji Government permitted to put the national landmarks. In 1895 the Senkaku Islands were placed under the jurisdiction of Okinawa Prefecture. In the same year, Tatsushiro Koga, who was a powerful and wealthy shellfish merchant, asked the Meiji Government to lease Kuba Island for the purpose of catching albatross because of the rapid decrease of the great green turban. His business changed from shellfish to albatross. In 1896, the Government not only leased Kuba Island to him but also granted him the lease of another four Senkaku Islands for 30 years.In 1897 Koga started his business in the Senkaku Islands, but albatross, his main resource of business, decreased devastatingly in only three years. Therefore, he diversified his business into stuffed birds, bonito fishing, guano, and phosphate rocks and managed to make an immense profit. But his business didn't last long because he mismanaged the natural resources on the islands. Koga Village, founded in Uotsuri Island with a huge investment of money, disappeared in about 30 years and around 1937 the Senkaku Islands again became uninhabited with no change since then.

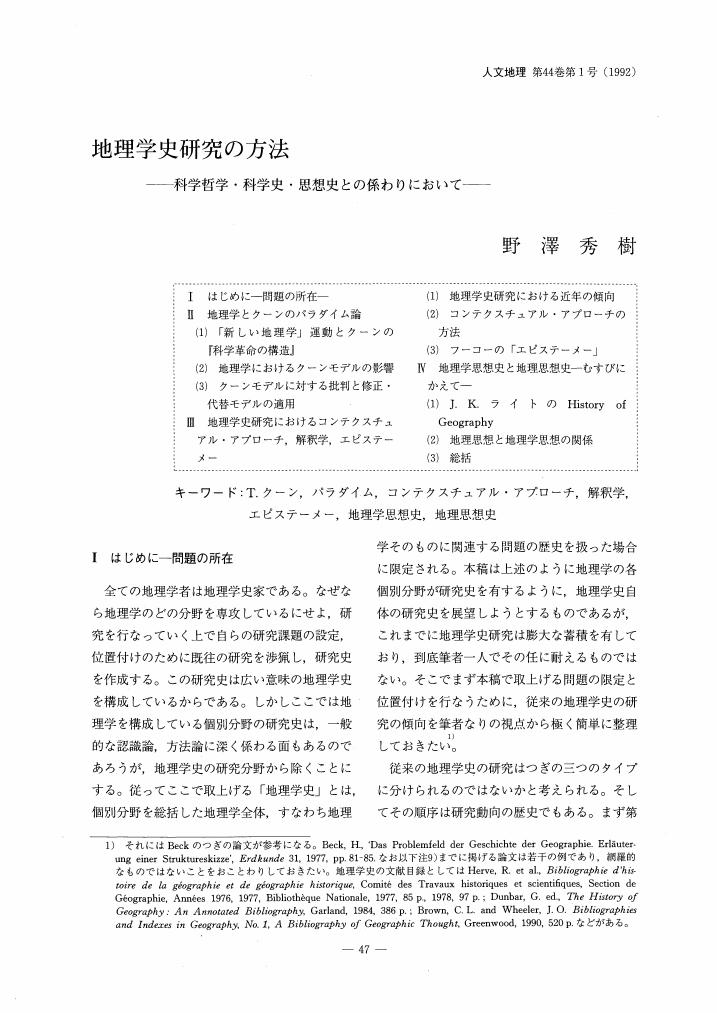

12 0 0 0 OA 地理学史研究の方法

- 著者

- 野澤 秀樹

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.44, no.1, pp.47-67, 1992-02-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 145

- 被引用文献数

- 4 1

12 0 0 0 OA 保倉川舊河道の中世開發水田

- 著者

- 籠瀬 良明

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2, no.3, pp.36-47,96, 1950-07-30 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 18

In the plain of Takada can be traced an old watercourse of the Hokura about five kilometers in length. What characterize this old watercourse are free meandering and natural banks, running on both sides of it and higher than the level by one meter or two with fields and hamlets on them. A long succession of fine paddy-fields stretehes on this old course of the river, which were brought under cultivation in middle ages. (Especially, it is the case with the lower course of the river.)In the article two of those examples, Matsuhashi and Funatsu in the village of Honda are dealt.[The author made a lecture on other such examples, Honda-Enokii and Katatsu, at the autumnal meeting of Association of Japanese Geographers last year, and explained why the region should be supposed to have been cultivated in Middle Ages, also explaining its characteristics. The details are to be mentioned in next number.]

11 0 0 0 OA 和人地・蝦夷地の境界とその変遷

- 著者

- エドモンズ リチャード

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.33, no.3, pp.193-209, 1981-06-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 74

- 被引用文献数

- 1

Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, Japan's northern island, Hokkaido, was divided into a Wajin-Japanese settlement exclave, called Wajinchi or Wajinland, and an area in which only Ainu were allowed to reside permanently, known as Ezochi. This paper looks at changes in the location of the boundary and in the function of guardhouses located near it as one way to analyze Tokugawa frontier policy. Sources include diaries of travelers, government documents, old maps, and sketches.Results show that the Wajinchi expanded in five stages. From the thirteenth to the mid-sixteenth century, Wajin-Japanese settlement remained in a punctiform pattern with forts spaced along the extreme southern coast of the Oshima Peninsula. This initial stage is characterized by a lack of unity among Wajin and relative strength of the Ainu.Next, an accord reached around 1550 between the strongest Wajin-Japanese leader and two Ainu chieftains delimited a conterminous zone on the southwestern tip of the Oshima Peninsula. This second phase suggest the unification of Hokkaido's Wajin was well underway.The Matsumae clan formed in the early seventeenth century, expanded the exclave, demarcated the boundary with poles, and established guardhouses. During the following two centuries, these efforts to partition the Wajin-Japanese and Ainu continued. It is of special note that the distance between Matsumae castle and the eastern and western boundaries was roughly equivalent.A major policy transformation occurred at the beginning of the nineteenth century when the Tokugawa government took over control of Ezochi, installed a magistrate in Hakodate, and extended the eastern portion of the Wajinchi. The concern of the Tokugawa government in the affairs of Ezochi was apparent since the new eastern guardhouse was located on the Ezochi side of the boundary, a condition. which had never previously existed.In the mid-nineteenth century, the Wajinchi was enlarged again. However, the absence of boundary guardhouses along with the lack of contiguity marked this as a transitional stage prior to the opening of the whole island for colonization in 1869.These Wajinchi expansions can be conceived of as concentric zones. The second and third stages surround Matsumae castle while the fourth and fifth have double foci, Hakodate and Matsumae, and generally encircle Hakodate. The lack of guardhouses in the second and fifth stages illustrates their transitional character in contrast to the third and fourth stages of Matsumae and subsequent Tokugawa direct control.

11 0 0 0 OA 愛知県常滑市における「ギャンブル空間」の形成

- 著者

- 寄藤 晶子

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.57, no.2, pp.131-152, 2005-04-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 53

- 被引用文献数

- 3

In this paper, the author argues that gambling businesses managed by public authorities face issues regarding monopolization, regulation of space and socio-spatial exclusion.Since the end of the 19th century, informal private gambling has been strictly outlawed in Japan, while both the national and local governments have resorted to investing in the gambling business to secure revenue. At present, with the exception of lotteries, 120 gambling facilities such as keiba (horse race), keirin (bicycle race on a short track), autorace (motorcycle race on a short track), and kyotei (motorboat race on a square pond) are offered by 21 prefectures and 443 municipalities. These are called "public gambling".In his book The Production of Space, Henri Lefevre notes that non-productive expenses are made according to the neocapitalist's interest. Therefore, the author refers to the three elements that constitute space according to Lefevre: spatial practices, representations of space and space of representations. The author conducted field work in and around the motorboat gambling facility operated in Tokoname City, Aichi Prefecture, and the highlighted the "gambling space" using Lefevre's scheme mentioned above.From 1997-2000, the author interviewed: Tokoname motorboat officers, residents from the areas (sinkai-cho) around the motorboat facility, police officers, members of the "koie-sinkai crime prevention association", a security guard and ticket sales women employed at the motorboat office, shop managers in and around the motorboat facility, and the motorboat gambling fans. The author also conducted participant observation studies of more than 400 motorboat gambling fans. The author's findings are as follows:Firstly, while the public authority, the Tokoname motorboat office, adopts several measures to draw visitors to the motorboat facility and thus ensure income, this practice includes spatial separation, i.e., separating the Tokoname motorboat gambling fans from the public. This is partly because the nature of gambling itself threatens social order, therefore, the public authorities control and enclose gambling fans. These practices of exclusion are observed in their spatial practices.Secondly, shops and restaurants are located on the route taken by visitors from the Tokoname railway station to the motorboat facility. These shops and restaurants sell alcohol, low-priced light meals and magazines or newspapers regarding gambling. Fans regularly take the route from the Tokoname railway station to the motorboat facility and purchase these goods from these shops. Loitering fans and torn blank tickets visibly distinguish the "gambling space" from the rest of the city. Japanese public gambling fans are largely men over 60 years of age. However, in Tokoname motorboat facility, 60-70% of motorboat gambling fans are men, who are 60 years and over. Therefore, the "gambling space" is occupied by middle and old-aged men is littered with blank tickets.Thirdly, measures adopted by the local community, the "koie-sinkai crime prevention association", neighborhood residents and the police to regulate the behavior of visitors' create negative representations of Tokoname motorboat gambling facility and its fans. In 1970, as the number of visitors increased, a few residents living around the motorboat facility founded a crime prevention association in order to put a burglar alarm to their house. At this time, the Tokoname motorboat office began sending presents, such as handkerchiefs, rice, pans and soaps as compensation to residents. The activities of "koie-sinkai crime prevention association" provided subsidies by Tokoname City, although they are not strictly monitored. They unfairly claimed and represented the undesirable behavior of visitors in order to protect their interests.

10 0 0 0 OA 日本における宗教地理学の展開

- 著者

- 松井 圭介

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.45, no.5, pp.515-533, 1993-10-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 127

- 被引用文献数

- 4 3

Geography of religion aims to clarify the relationships between the environment and religious phenomena. In Japan, this discipline has four major fields of researchThe first field is that of the relationships between the natural environment and religion. The emphasis in this field, however, is on the influence of the environment upon religion. Whereas many scholars study how climate and topography change the formation of religious beliefs, there is almost no study of the influence of religion upon the natural environment. In order to fill this lack, it is necessary, for instance, to clarify the role of religion in environmental protection.Secondly, geographers of religion study how religion influences social structures, organizations, and landscapes in local areas. They mainly examine the urban structure and its transformation within religious cities with regard to the dominant religion. There are also some studies about the significance of religion for the formation of new cities. The relationships of the religious orientation to the local structure of cities and villages, however, has not been thoroughly clarified yet.Thirdly, pilgrimage forms another major field of research in the geography of religion. Most studies so far, however, remain preliminary, showing the routes of pilgrimage without reconstructing networks among sacred places and their surroundings. Moreover, the contemporary meaning of pilgrimage is not studied enough, though people today still carry out pilgrimages fervently.Lastly, geographers of religion try to clarify the structure of space which is created by the sacred, through examining the distribution and propagation of religion. One of the major studies in this field is that of sphere of religion.This geography of religion as the study of relationships between the environment and religion has two indispensable approaches, for the space created through these relationships has two aspects; empirical and symbolic. On the one hand, religion has power to organize local communities and this power generates the structure of space which is grasped empirically. On the other hand, religion supports human existence through offering a cosmology. This cosmology appears in the structure of space symbolically. Geography of religion should understand the religious structure of space throughly by adopting both positivistic and symbolic approaches.

10 0 0 0 OA 輪島市海士町の漁民集団

- 著者

- 祖田 亮次

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.48, no.2, pp.168-181, 1996-04-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 38

- 被引用文献数

- 1

The fishing group of Amamachi community, at the tip of the Noto Peninsula jutting out into the Japan Sea, is very distinctive in terms of life style. It has thus attracted many previous studies on this group in various disciplines. Most of them, however, have tended to demonstrate its uniqueness by introducing its uncommon customs. Nevertheless, such a conventional view should be modified now: this group, I think, is typical of kaimin (maritime people), one of the major marginal groups, whose importance has been r6ather neglected so far due to an influential and far-reaching point of view focused on rice cultivation.In the third section, the primary purpose to see them within the whole context of Japanese society in the right perspective was pursued. To do so, their situation was investigated in reference to kyakumin (major marginal people with autonomy) or kaimin with their own histories different from paddy-cultivating people. Unlike most kyakumin/kaimin groups, which have been weakened, dissolved or extinguished because of their failure in coping with new situations brought by changes over time, the Amamachi community has lasted well until now. Its sustainability deserves careful attention.Amamachi's fishing people are considered to be descendants of fishing people of Kanegasaki District located in the northern part of Kyushu. Since their arrival at the Noto Peninsula, they had been engaed in diving fishing under the protection of the Kaga Clan (Maeda Territory) until the end of the Edo Period (1603-1867). They had been conscious of their distinct characteristics and confirmed the difference between their own and surrounding societies by stressing their relation with the Kaga Clan and by remembering their own historical origin. Such an attitude was effective in keeping the autonomy of the group against the dominance of shumin (main people) engaged in paddy cultivation. In this sense, the Amamachi community indicated a prominent characteristic corresponding to that of kyakumin.On the other hand, another characteristic of theirs as kaimin is found in the following attitudes: wider mobility to seek better fishing grounds and acquire new trading areas, aggressive fishing methods based on high technical skills, and indifference to agriculture in general.In the fourth section, the second aim of this paper to substantiate the sustainability of the community was explored chiefly by tracing changing processes of systems and customs of their society. In particular, I devoted attention to the two periods when the community confronted crises of existence: the time of the second half of the nineteenth century, when the modern age began in Japan, and the high economic growth period in the mid-twentieth century. Their reponses for surviving can be summarized as follows:As for the second half of the nineteenth century, because of the collapse of the Bakufu-system, the relation between the Kaga Clan and this community was annulled. This implied that they would lose the exchange route for marine products and agricultural crops. Fortunately, however, a loose stratification occurred in this period, resulting in an establishment of the oyakata-kokata (patron-client) relation. While oyakata newly came to be in charge of the exchange instead of the Kaga Clan, kokata could peddle their extra products individually-this was called nadamadari (peddling trip)-. This suggests that newly emerged oyakata had a certain power, but nadamawari and other community controls restrained an excessive stratification.With respect to the high economic growth period, the wide diffusion of powerboats improved fishing productivity and accelerated the monetary economy. These changes caused a dissolution of oyakata-kokata relation and a decline of nadamawari.