2 0 0 0 OA 鎌倉後期・建武政権期の大覚寺統と大覚寺門跡 : 性円法親王を中心として

- 著者

- 坂口 太郎

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.122, no.4, pp.459-497, 2013-04-20 (Released:2017-12-01)

In recent years, particular attention has been drawn to the retired Emperor Go-Uda's 後宇多 promotion of esoteric Buddhism and it surrounding cultural and political environment as the staging ground for the "anomalous (igyo 異形) monarchical regime" of his son Emperor Go-Daigo 後醍醐. This paper discusses the relation between the Daikakuji 大覚寺 line of imperial descent and its "monzeki" 門跡 (Buddhist temples designated for tonsured members of the imperial family, also referred by the title of monzeki) during the late Kamakura and Kenmu 建武 Regime periods, by focusing on prince-monk Shoen 性円 (Go-Daigo's brother), who was chosen as the Daikakuji Monzeki. Little is known about the early life of Shoen, who is generally referred to as "Daikakuji-miya"; however, the author's investigation of yet unpublished historical sources place him at Yasui Monzeki 安井門跡 (Rengeko-In 蓮華光院), which was affiliated to the Ninnaji-Goryu 仁和寺御流 branch of Shingon Buddhism. Given the additional fact that Go-Uda originally planned to take control of Ninnaji-Goryu, the author concludes that Shoen's assumption of Yasui Monzeki was part of his father's overall religious policy. Then Go-Uda founded the Daikakuji Monzeki, providing it with proprietary estates and sub-temples, and transfered his son to Daikakuji, making Shoen his possible successor. The author also points out that in his struggle with Ninnaji, Go-Uda bestowed on Shoen the second highest princely rank and such imperial household treasures as the cintamani jewel. Moreover, in his later years Go-Uda repeatedly performed esoteric Buddhist rituals for the protection of the Daikakuji line, and had Shoen participate in them to train him for his future calling. After Go-Uda's death, Shoen became the abbot of Daikakuji, supporting Go-Daigo, who sent his own son Gosho 恒性 to serve as a priest at Daikakuji, and the fact that Gosho would later be banished to Etchu 越中 Province by the Kamakura Bakufu and then assassinated shows without a doubt that he was part of the plan to overthrow that military regime. Hence, it is likely that because of its control over a large number of proprietary estates, Go-Daigo depended heavily on the Daikakuji Monzeki in his plans to overthrow the Bakufu. As for Shoen during the Kenmu era, in addition to his performance of esoteric Buddhist rituals, he served as a general on the field of battle. Moreover, after the fall of the Kenmu regime, Shoen continued to serve the Southern Court. Since the publication of Amino Yoshihiko's seminal work on the period in question, the research has been focused on the Shingon priest Monkan 文観, in order to elucidate the religious aspects of Go-Daigo and his reign. However, if one considers the historical developments from the time of Go-Uda, it becomes clear, as this article shows, that it was not Monkan, but rather the Daikakuji Monzeki allying with the Daikakuji line of descent led by Shoen, which lent the primary support to Go-Daigo's regime from within the walls of Shingon Buddhism.

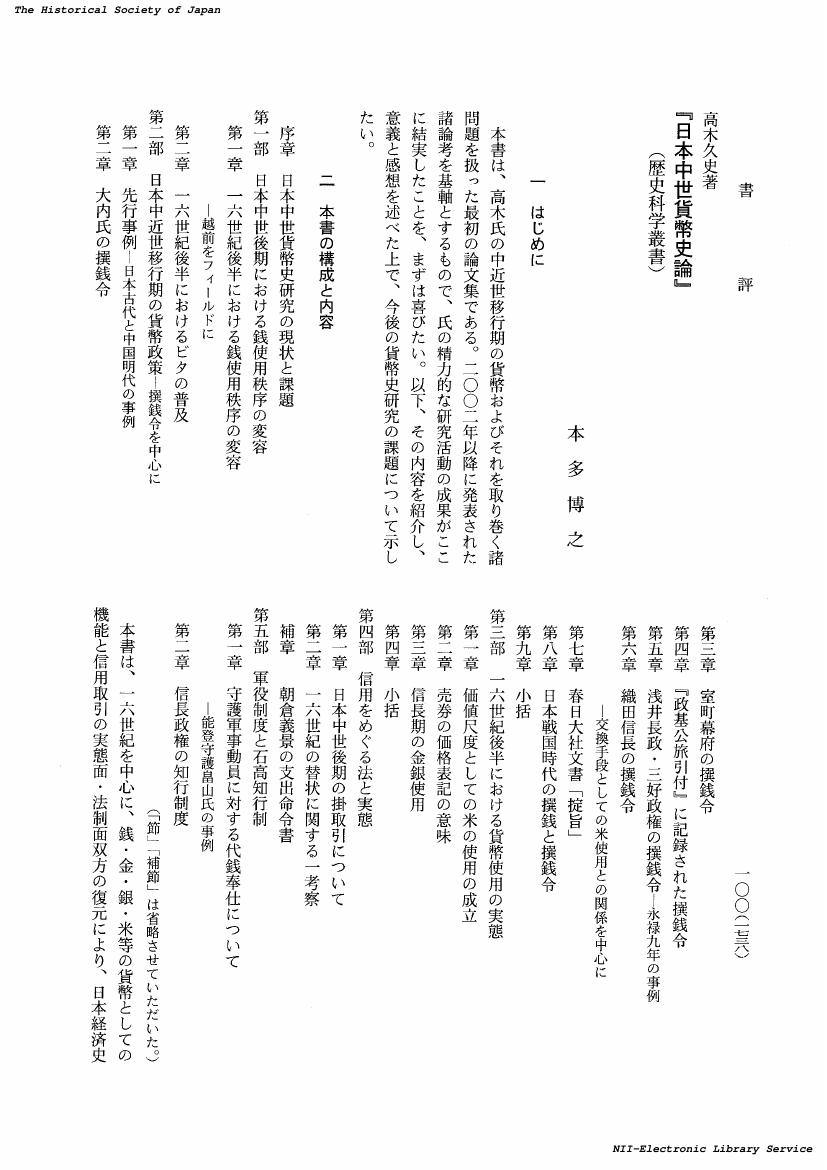

- 著者

- 本多 博之

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.120, no.10, pp.1738-1746, 2011-10-20 (Released:2017-12-01)

2 0 0 0 OA 前漢の監察体制について : 武帝期を中心に (東洋史部会 研究発表)

- 著者

- 王 勇華

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.106, no.12, pp.2173, 1997-12-20 (Released:2017-11-30)

2 0 0 0 OA 明治政府のキリスト教政策 : 高札撤去に至る迄の政治過程

- 著者

- 鈴木 裕子

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.86, no.2, pp.177-195,242-24, 1977-02-20 (Released:2017-10-05)

In March Cf 1868, the Meiji government's regulations against Christianity were made public. These new regulations in terms of content were inherited directly from the Bakufu. This decision was due to the complicated state of national affairs which included attacks on the government by the remnants of the Bakufu army and the ongoing clashes between foreigners and anti-foreigners. However, once these regulations were issued as law, the government had to preserve them, lest any change weaken its own authority and become a source of criticism against the government by those elements opposed to the new Meiji regime. The exiling of the thirty-four hundred Christians from Urakami Village in Nagasaki was the largest concession the Meiji government could make to foreign countries. This decision was implemented in December of 1869 despite delays resulting from the war. At first, the regulations concerning Christianity had no connection with the plan to make Shinto the established religion. However, this link was made during the government's efforts to retain the anti-Christian regulations. Accordingly, though the government promised generous treatment to foreigners after the Urakami villagers had been exiled, the government did not have any concrete plans to carry out its promise. Only in the fall of 1870 did Christianity become a subject of lively debate in the government, and that was simply because there was a fear of a problem possibly taking place in Kagoshima, the home of many important people in the government. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which had been receiving a constant stream of protests from foreign countries, understood that the problem of Christianity in Japan was an important one in foreign affairs. Yet, it had little power in the government and so did not participate in the making of government policy decisions concerning this issue. Nonetheless, the Foreign Ministry had continued to appeal to the government to keep the promises it had made to other countries. In the spring of 1871 the central government's suppression of the rebel forces ended in success. In July of the same year the "han" system was dissolved and replaced by the "ken" system of local government. As the government continued to centralize power and to institute organizational changes in the governmental system, it then began to show its willingness to change its policy by its handling of the Imari Incident in Saga and its release of those Urakami villagers who had given up their belief in Christianity. Also emerging at this time were demands for the end of any anti-Christian regulations by members of Japanese governmental missions in Europe and America. In February of 1872 when the government's concern over the discontented elements in Japan had come to an end, the enforcing of anti-Christian regulations also came to an end. In this way we can see that while the Meiji government's policy towards Christianity was a concern of Japanese foreign policy, essentially it was influenced more by domestic political factors and changes during this Period.

2 0 0 0 OA 西欧・南欧(中世,ヨーロッパ,二〇一〇年の歴史学界-回顧と展望-)

- 著者

- 近江 吉明

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.120, no.5, pp.940-945, 2011-05-20 (Released:2017-12-01)

2 0 0 0 OA 公議輿論と万機親裁 : 明治初年の立憲政体導入問題と元田永孚

- 著者

- 池田 勇太

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.115, no.6, pp.1041-1078, 2006-06-20 (Released:2017-12-01)

The present article attempts to clarify the birth of monarchical constitutionalism on the occasion of a debate over a popularly elected parliament in 1874, by focusing on Motoda Nagazane (or Eifu) 元田永孚, who was Emperor Meiji's tutor in Confucianism. The introduction of a constitutional polity in the absence of a government not only displayed the strong character of a modernization measure and was thought to realize a political society supported by the masses and open public opinion, but also a parliament, constitution and separation of the legislative and administrative branches of government were expected to solve real problems that existed in local administration and politics at the time. The article begins with an examination of the actions taken by the Governor of Fukushima Prefecture Yasuba Yasukazu 安場保和 in order to clarify the era's parliamentary movement against the background of local administration and to argue that the fair and just nature (ko 公) of a constitutional polity was thought to be identical to traditional Confucian political ideals. Secondly, the introduction of a constitutional polity at that point in time was not the result of power politics fought along vertical, class lines, but was rather a specific political expression of what the Restoration bureaucracy thought desirable. On the other hand, the introduction of such a polity under well-meaning auspices from above also meant that the bureaucracy did not always seek broad pluralistic opinions on the subject, but rather tended to make policy decisions in a more theoretical manner. The 1874 debate over a popularly elected parliament brought the issue of mass popular political participation to the forefront in terms of "joint rule by king and citizen." It was here that Motoda Eifu suggested that in a monarchical state it was necessary to make a distinction between "public opinion" and "the just argument," arguing that it was the monarch who should employ the latter. Any parliamentary system in which the monarch enjoys ultimate prerogative, moreover, demands that the monarch have the ability to exercise that prerogative properly, which necessitated the development of a system of imperial advisors and educators. At that time there was also the idea that the position of senior political advisor (genro 元老) should be created outside of the cabinet to perform such a function. Motoda, on the other hand, reformed such an idea based on the necessity of a monarch performing his duties with the final say within a constitutional polity. This is why it can be said that both monarchical constitutionalism and the establishment of the emperor's prerogative within it was born out of the 1874 debate over a popularly elected parliament.

2 0 0 0 OA 初期中世アイルランドにおける婚姻と女性の権利 : 『アイルランド教会法令集』を通して

- 著者

- 田付 秋子

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.108, no.12, pp.2177-2178, 1999-12-20 (Released:2017-11-30)

2 0 0 0 歴史理論 (1976年の歴史学界--回顧と展望)

- 著者

- 堀越 孝一

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.86, no.5, pp.p500-504, 1977-05

- 著者

- 紺谷 由紀

- 出版者

- 史学会 ; 1889-

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.125, no.6, pp.1053-1088, 2016-06

- 著者

- 満薗 勇

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人史学会

- 雑誌

- 史學雜誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.118, no.9, pp.1643-1666, 2009-09-20

The purpose of this article is to examine the effect of cash on delivery service on the development of the mail order business in prewar Japan. C.O.D. was established as a postal service in 1896, and helped decrease the business cost incurred by time lags between the settlement and delivery of parcels. In addition, the fact that C.O.D. was provided as a governmental postal service was significant in three ways. First, a nationwide postal network was made available to users, including those in rural areas. Secondly, settlement and delivery was implemented without any problem. Thirdly, suppliers who dispatched goods via C.O.D were regarded as reliable dealers. Consequently, the mail order business was made available to all suppliers, regardless of their sales volumes, and developed rapidly, to the extent that by 1922, Japan rose to second in the world behind Germany in the number of C.O.D. parcels delivered in 1922 (no statistics are available for the US and UK). However, after 1923, the service experienced little growth, owing not only to such environmental factors as the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, the Showa financial panic of 1930, and the increase of retail outlets; but also because 1) it was impossible to prevent fraud on the part of unscrupulous businessmen peddling goods of inferior quality, due to the failure to implement an inspection system, and 2) the decision on the part of the postal service to end door-to-door delivery of C.O.D. parcels due to budget constraints. Consequently, the number of parcels returned to sender increased, burdening suppliers with the cost of postage and handling and the loss of a sale opportunity for the returned goods.

2 0 0 0 守護支配の展開と知行制の変質

- 著者

- 岸田 裕之

- 出版者

- 山川出版社

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.82, no.11, pp.1-42, 1973-11

- 著者

- 鈴木 淳

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人史学会

- 雑誌

- 史學雜誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.109, no.6, pp.1214-1215, 2000-06-20

2 0 0 0 義和団(拳)源流 : 八卦教と義和拳

- 著者

- 佐藤 公彦

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人史学会

- 雑誌

- 史學雜誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.91, no.1, pp.43-80, 145-143, 1982-01-20

Eight trigrams sect (Pa-kua-chiao 八卦教) was the most popular religious secret society in north China through the Ch'ing dynasty, and in the process of its expansion we can often find a lot of boxing training by its members. In this paper we will consider the relationship between the Eight trigrams sect and boxing training such as I-ho-chuan (義和拳), etc.. Eight trigrams sect is said to have been founded by a man called Li Ting-yu (李廷玉) in either the Shun Chih (順治) or Kang Hsi (康煕) reign periods at the beginning of the Ch'ing dynasty. It was organized according to the principle of the division into eight trigrams, and also divided into a "Wen" (文) or literary sect, and a "Wu" (武) or military one which had widely developed itself ; the society consisted of four "Wen" trigrams and four "Wu" trigrams. The combination of Eight trigrams sect and boxing training had already taken place in early Yung Cheng (雍正) period. In the Wang Lun (王倫) rebellion (1774), which was raised by a society called Ching-Shui-Chiao (清水教), a branch of the Eight trigrams sect, the boxing styles used inside the sect had been Pa-kua-chuan (八卦拳, Eight trigrams boxing), Chi-hsin-hung-chuan (七星紅拳 Seven star red boxing), and I-he-chuan (義合拳, Righteous harmony boxing). From this we can see that the I-ho-chuan was the same as the White Lotus religion or more precisely as the boxing which had combined with the military sect of Eight trigrams sect, Ching-Shui-chiao. From the incident of the I-ho-chuan in 1778, 1783 and 1786, we can guess that the I-ho-chuan had close relationship with the Li (離) trigram, a branch of the Eight trigrams sect. In 1813, Eight trigrams sect raised an uprising. A careful examination of the materials on the boxing in this uprising such sources as those on general leader of the military sect, Feng Ke-shan (馮克善), the group members led by Sung Yueh-lung (宋躍〓) and the case of Ke Li-yeh (葛立業) who learned and practiced I-ho school boxing (義和門拳棒), show that I-ho school boxing had been practiced inside Sung Yueh-lung's group in the Chili-Shantung boundary area, and that this group belonged to the chain of Li trigram. Hence we can easily identify the I-ho school as one of small regional group in the Li trigram in Eight trigrams sect. It becomes clear that the reason why boxing was combined with the Li trigram, representative of Wu trigrams, depends on the principle of organization. The boxing practiced in the Eight trigrams sect had been influenced by its religious thought, and came to have incantationary-religious characteristics, The I-ho-chuan and Eight trigrams sect in Chin-hsiang (金郷) county seem as though they were in conflict, but this example proves that there was a close relationship between the two. It is clear that historically boxing such as the I-ho-chuan, Pa-kua-chuan, etc., expanded widely in the north-west Chili-Shantung boundary area and south-west region of Shantung, by maintaining continuous relationship with Eight trigrams sect. Another phenomenon, however, also appeared. Social disturbance and confusion after the late Tao-Kuang (道光) period, brought about a wide expansion of the boxing training that was not directly related with Eight trigrams sect. The boxing which had combined with Eight trigrams sect, though taking on religious character, gradually started to secede from it, was accepted as a function of violence or defence in rural society. In the Hsien-Feng (咸豊) and Tung-Chih (同治) Periods, boxing which had permeated into rural society gradually came to be related to "Tuan militia" (団) and the "Allied village societies" (lianzhuanghui 連荘会) coexisted with the order of rural society, and built up the social foundation for the organization of I-ho-chuan society. Eight trigrams sect, not only scattered widely in this way, but also combined forces with bandits in the process of the mutual permeation with these military plunderers' groups. Thus some societies -such as Long Spea

- 著者

- 水間 大輔

- 出版者

- 史学会 ; 1889-

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.125, no.8, pp.1446-1455, 2016-08

2 0 0 0 ミルダース朝の外交政策 : 西暦十一世紀のアレッポを中心として

- 著者

- 太田 敬子

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人史学会

- 雑誌

- 史學雜誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.101, no.3, pp.327-366, 490-491, 1992-03-20

The Mirdasid dynasty ruled Aleppo and its region in northern Syria from 415 A.H./1025 A.D. to 473 A.H./1080 A.D.. The Mirdasid was a family of the Kilab tribe (Banu Kilab) which belonged to the northern Arab tribes. Banu Kilab, taking advantage of political disorder caused by the decline of the 'Abbasid's rule, had extended their influence into the Aleppo region. The Mirdasid principality was founded upon their strong military power. This paper aims to investigate the first period of the Mirdasid dynasty on the point of foreign policy and influence in the international relations. From the middle of the tenth century, the Aleppo region had been threatened by two powerful foreign states; the Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt and the Byzantine empire, both of which aimed to annex this region. Under such circumstances, Salih b. Mirdas, the first prince of the Mirdasid dynasty succeeded in gaining control of Aleppo city with support of a Syrian Arab alliance. To extend their power, the Mirdasides made use of the balance of power between these Great Powers and their limited ability to advance their territorial ambitions into Syria. The principal approach to their foreign policy was to negotiate with each of them, receive their recognition for possession of Aleppo, and then nominally establish an independent state under their patronage. However, before receiving their recognition, the Mirdasides had to engage in some battles with them. As a result, Thimal, the third prince, succeeded in obtaining recognition as the ruler of Aleppo from both of the Great Powers and stabilized the supremacy of the Mirdasid dynasty in the Aleppo region. However, the author has also ascertained that this success owed much to the internal affairs of the Fatimid caliphate and the Byzantine empire and changes that occured in the diplomatic relations between them. The author also examines concretely the position of the Mirdasid princes in international relations. As a result, she has found that their subordinate posture in the diplomatic negotiations did not mean a dependent character. It should be noted that recognition from foreign powers to be the governor of Aleppo was indispensable for the Mirdasid princes to achieve stability within their states ; and to receive such recognition was the principal purpose of their foreign policy.

- 著者

- 武藤 滋

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人史学会

- 雑誌

- 史學雜誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.100, no.9, pp.1637-1638, 1991-09-20

- 著者

- 泉 卓也

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人史学会

- 雑誌

- 史學雜誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.101, no.1, pp.133-135, 1992-01-20

2 0 0 0 書評 山川均著『石塔造立』

- 著者

- 大塚 紀弘

- 出版者

- 史学会 ; 1889-

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.125, no.6, pp.1120-1129, 2016-06

- 著者

- 小澤 実

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人史学会

- 雑誌

- 史學雜誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.116, no.8, pp.1414-1415, 2007-08-20

2 0 0 0 アメリカの対日外交と北太平洋測量艦隊 : ペリー艦隊との関連で

- 著者

- 後藤 敦史

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人史学会

- 雑誌

- 史學雜誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.124, no.9, pp.1583-1606, 2015-09-20

The research to date on the fleet of the United States North Pacific Exploring and Surveying Expedition (NPSE), which visited Shimoda in May 1855, has concluded that the fleet's aim was to test the effectiveness of the treaty of peace and amity between Japan and the United States, known as the Kanagawa Convention (concluded 31 March 1854), under direct orders issued by the US Secretary of the Navy, despite the fact that the Convention had not yet been concluded when the NPSE departed from Norfolk, Virginia, in June 1853. The purpose of this article is to reveal more concrete detail the diplomatic purposes and reasons behind the NPSE's visit to Japan. It was in August 1852 that the NPSE was scheduled to be dispatched to survey the North Pacific maritime region, as part of US Navy and State Department policy aimed at challenging British hegemony and protecting whale fisheries in the region. While these objectives were similar to those of Commodore Perry's expedition to Japan, the NPSE also intended to negotiate with countries that Perry had not visited. This means that both Perry's expedition and the NPSE were equally important to US diplomacy regarding the North Pacific region. However, the two expeditions did not always cooperate. For example, the NPSE had to suspend its surveying activities when it arrived at Hong Kong in May 1854, because Perry had concentrated his vessels in Japan, leaving no US ships in the South China Sea to protect American merchants during the confusion created by the Taiping Rebellion. Finally, the author shows that when the NPSE did arrive in Shimoda, its aim was to open negotiations with Japan, not on the orders from the Navy, but on the decision of the NPSE Commander John Rodgers himself. Before heading for Japan, the NPSE visited the Ryukyu Kingdom, where Rodgers judged that the treaty between the Ryukyus and the United States, which had been concluded by Perry, was being violated by the government of the Ryukyus, a perception that probably influenced his decision to proceed to Japan. Contrary to the widely held view, the author shows that the Secretary of the Navy did not order the NPSE to visit Japan with the purpose of testing the effectiveness of the Convention of Kanagawa and calls for a reconsideration of the character of US diplomacy regarding the Pacific Ocean region, in general, and Japan, in particular during the mid-19th century.