2 0 0 0 OA メラネシアの経済と,原始共産主義理論(B.マリノフスキー)

- 著者

- 石川 榮吉

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.4, no.6, pp.521-522, 1953-02-28 (Released:2009-04-30)

- 著者

- 松田 敦志

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.55, no.5, pp.492-508, 2003

- 被引用文献数

- 1

In the suburban residential areas developed before World War II, some problems, such as the division of a housing lot, the rebuilding of a residence and the progress of aging, have been arising recently. Development of residential suburbs before the war is thought to be a part of urban development and to have produced the present life style, that is, the separation of home and workplace so that it has an important historical meaning from the viewpoint of the formation of city and urban life style.<br>We cannot ignore the private railway company, especially in Kansai region, when we consider the developments of residential suburbs. Therefore, in this paper, I study the private railway company that has influenced developments of residential suburbs. And I clarify its management strategy and the specific characteristics of the residential suburbs developed by the private railway company, Osaka Denki Kido Railway Company.<br>It was necessary for the private railway company to increase transportation demand by carrying out various activities, in order to secure stable income, because it had only one or a few short and local railway lines. But, since Osaka Denki Kido Railway Company had many sightseeing spots along its line, it first aimed for the stability of management not by developing any areas along its line, but by promoting its sightseeing areas and expanding its routes. However, it began to set about the developments along its lines gradually after the end of Taisho Period. It developed the residential areas along its lines, utilizing the advantage as a railway company, for example, preparation of a new station and offering a commuter pass as a gift to people who moved to residential areas along its lines. Some characteristic scenes such as little streams and roadside trees, some urban utilities and facilities such as electrical and gas equipment, some playing-around spaces such as parks or tennis courts, which the middle class who were aiming for a better life wanted, were prepared in these residential areas. It tried to obtain constant commuting demands by urging them to move to these suburbs.<br>For example, it connected its route to Yamamoto and built a station there consciously. And then, it developed the residential areas around Yamamoto Station in collaboration with the Sumitomo Company. Osaka Denki Kido Railway and Sumitomo produced the image of residential suburb as an education zone by inviting schools there, and tried to maintain the good habitation environment by imposing housing construction regulation on residents. In this way, many of the middle class families moved into the residential area at Yamamoto before the war. Moreover, Osaka Denki Kido Railway encouraged residential developments around that area, and consequently the suburbs were expanded.<br>After all, Osaka Denki Kido Railway produced some residential suburbs along its line for the middle class before the war, although that time was a little later compared with Hankyu Railway. The reason was that its management strategy was to secure stable demands of transport. As suburban life grew up gradually there, that increased the number of suburban residents, and the residential suburbs were developed around them further. In other words, Osaka Denki Kido Railway has been responsible for the expansion of the suburbs.

2 0 0 0 OA 羽田空港直行バス網の拡大とその要因

- 著者

- 安達 常将

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.57, no.2, pp.173-194, 2005-04-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 102

- 被引用文献数

- 1

After the deregulation of air transport in United States and liberalization in Europe, papers on this theme have been accumulated in the field of transport geography which uses quantitative methods in United States and Europe while there are few socio-economic studies from that viewpoint. Socio-economic transport geography tends to have an interest in historical processes of transport development and little in the current transport problems especially in Japan. Socio-economic studies, however, examine the system of transport facilities comprehensively, which will contribute to practical analysis and criticism of current transport problems.The purpose of this paper is to examine the case of the rapid expansion of the direct bus network connecting Haneda Airport with its hinterland since the latter half of the 1990s. This paper also examines the other social background of this phenomenon, considering the role of bus company in making the bus routes between Haneda Airport and its hinterland, impact of the deregulation of air and bus transport, changing use of aircraft, and the bus share in airport-access market. The data were mainly collected through interviews with the personnel of bus companies in charge of planning bus route to Haneda Airport. The main findings of this paper are summarized as follows:1. Almost all the bus routes between Haneda Airport and its hinterland are managed by two airport bus companies (Keihin Electric Express Railway Co., Ltd., and Airport Transport Service Co., Ltd.), and 25 local bus companies, each of which has its own service area. Therefore the airport bus companies are concerned with all bus routes and have a lot of information on them. When the local bus companies plan to extend their bus routes into Haneda Airport, the airport side supplies accumulated know-how to run an airport-access bus with the local bus side. This cooperated-route-management-system enables a sudden increase in bus route.2. Until the first half of the 1990s, bus stops were arranged only in the Tokyo Bay area and Central Tokyo, which is near Haneda Airport. But the hinterland greatly expanded in 1998, reaching 100km away from Haneda Airport. Since these routes were profitable, the airport bus companies began to develop the bus route to Haneda Airport positively. Therefore the local bus companies have become so easy to participate in the airport-access bus that 13 routes were formed in 2000. After 2001, new routes have extended into areas where market size is smaller or road accessibility is worse, and 49 bus routes to Haneda Airport have been formed before December, 2002.3. The number of air passengers using Haneda Airport has increased from 31 million persons in 1988 to 54.8 million in 2000 and is estimated to be increasing in the future. This trend has brought an increase in airport-access bus passengers, too, and is one of the factors causing the expansion of the direct bus network connecting Haneda Airport with its hinterland.4. Haneda Airport Offshore Expansion Project has influences on the increase of passengers using Haneda Airport indirectly and on airport-access bus at three viewpoints. The number of bus stops has increased 5 to 15; many buses can be operated. Since highway system is improved, buses can arrive at Haneda Airport on time, which makes air passengers take a bus confidently. The pollution issues such as the noise and vibration are refined; aircraft can take off and land on Haneda Airport all day long. In the early morning, however, airport-access trains are not available in many areas in Haneda Airport hinterland while buses are available even in the areas more 100km away from Haneda Airport. This fact suggests that the bus companies could make buses bound for Haneda Airport run selectively in the early morning for their profit; on the other hand, this promotes the public benefit because the completion of airport-access is demanded now.

2 0 0 0 変貌する水産養殖業地域:的矢湾のカキについて

- 著者

- 大島 襄二

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.9, no.1, pp.16-28,82, 1957

The seaside villages of Matoya Bay, located at the middle of the Shima Peninsula (Mie Prefecture), were known by the name of Matoya Oyster, which was comparable with Miyagi Oyster or Hiroshima Oyster. Moreover, this peninsula is so famous for the cultured pearl, especially at Ago area, that this Matoya area, standing very close to the place, it is inevitable to be influenced by that.<br>This paper has an aim to analyse the character of this area from the viewpoint of marine farmings, especially the relation between oyster culture and pearl culture.<br>Matoya Bay is very unique in topographical features, very remarkable drowned-valley: the length is over 10km from the entrance of this bay to the inner end, and the width is only about 100m at the narrowest part of channel, or at most 1200m at the mouth of the bay.<br>This bay is divided as follows:<br>Demension of water surface Depth of water<br>A) Izô-ura 2.0km<sup>2</sup> 1-3m<br>B) Channel part 2.5km<sup>2</sup> 3-7m<br>C) Mouth of bay 7.5km<sup>2</sup> 5-10m<br>On the total of this bay, it has about eight time's demension of the catchment of water, but at Izô-ura, the most inner part of this bay, the catchment area is over 35 times as wide as that of water surface. This fact is that, the bay is very much influenced by the rainfall, and it is not so good condition to pearl culture, but desirable to oyster culture, for these marine farmings depend on the salinity of water. From this point, it is thus considered that the part A is the most prosperous part of oyster fishing. Actually, it was so, till the oyster fishery did not develop to oyster culturing. But about 1930 (the early years of Shôwa), some epoch-making change came to this fishery. That is hang-down method of oyster culture. This method has been used on pearl culture about 50 years before, and, when it was applied to oyster, Izô-ura is too shallow to this mothod. Then, at this part, people gave up this fishing, and this part became only supplier of fishing labour of the other part, or the other labour.<br>Parts B and C, two marine farmings are standing now. It is a little dangerous to pearl, for the salinity of water is not always good for it. Nevertheless, as the profit of pearl culture is larger than the other, so it is generalized at this parts of Motoya, at some risk, especially after the war. During the wartime, pearl culture was prohibited, while oyster culture was promoted, this parts of bay were filled by rafts of oyster, but now they are altered by rafts of pearl.<br>Now Matoya area is no longer the place of oyster production, but it shows the aspect of Ago area, and pearl culture is much attractive to these villages.

- 著者

- 梶田 真

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.66, no.5, pp.423-442, 2014 (Released:2018-01-27)

- 参考文献数

- 101

- 被引用文献数

- 1

Between the 1990s and 2000s, Anglophone researchers engaged in active discussions concerning policy relevance, the so-called ‘policy (re)turn’ debate. This debate occurred almost exclusively among academics, or what might be termed ‘pure’ geographers, and lacked participation from applied geographers and practitioners. This paper seeks to clarify the nature of these debates in the field of applied geography. Furthermore, this work examines relationships between applied geographers, so-called geographic practitioners, and “pure” geographers as well as academic establishments in the Anglophone world, especially in the United States, since the 1970s.First, this paper traces developmental processes within the field of applied geography since the early 1970s. In contrast to the pattern in Europe, within American academia applied geography lost vigor because of the strong theoretical focus that gained popularity in the discipline. This shift might be termed the rise of the ‘new geography’ within American academia. Additionally, another factor was a growing demand for positions at the level of university teaching staff owing to postwar economic prosperity and the entrance of baby boomers to university.There was, however, a resurgence of applied geography shortly after this initial decline of practical studies in favor of theoretical research. Following the relevance debate and the decrease of student enrollment within the field, applied geography began to once again gain popularity in the 1970s. These changes in the discipline were mainly brought about by state universities. These institutions were highly dependent on state subsidies and were therefore also governed by state policy. The geographical academies also pushed for the development of the field of applied geography. The Applied Geography Specialty Group (AGSG) and the James R. Anderson Medal of the Association of American Geographers (AAG) were established for distinguished applied geographers. Academic journals such as Applied Geography were also launched in the early 1980s.Since the 1990s, there has been a rise in geographical information technologies such as geographic information systems (GISs) and remote sensing. Owing to the popularization of the field through technological developments, an interest in geography was developed outside of the academic discipline. Following this development in the discipline, the National Research Council (NRC) published two documents, Rediscovering geography (NRC, 1997) and Understanding the changing planet (NRC, 2011). These reports emphasized the relevance and applied aspects of geography.However, academic studies in applied geography did not flourish in comparison with institutionalized progress within the field. Academic journals and sections of journals allotted to applied geography stagnated or were discontinued. Results taken from a citation analysis of journals such as Applied Geography and other key human geography journals demonstrate a lack of interaction between ‘pure’ geographers and applied geographers.This paper further discusses relationships between ‘pure’ geographers and academic establishments within the discipline of geography. ‘Pure’ geographers tended to criticize applied geographers for their lack of theoretical and philosophical grounding. They further critiqued applied geographers as free riders of geographical methodologies who made little contribution to their evolution. ‘Critical turn’ movements in geography led ‘pure’ geographers to exclusively concentrate their interests even further on thoughts and concepts in methodology with a philosophical background. Owing to these debates, these scholars asked applied geographers to reconsider the foundations of their research area and the relevant questions.[View PDF for the rest of the abstract.]

2 0 0 0 OA 現代のたばこ広告にみる男性の身体と空間

- 著者

- 村田 陽平

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.57, no.5, pp.532-548, 2005-10-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 56

- 被引用文献数

- 1 1

The consideration of male bodies is a significant issue for gender studies in geography since they are an influential factor in constructing gendered spaces. Few studies, however, have paid attention to male bodies, a fact that contrasts starkly with the amount of attention directed toward female bodies. Thus, the objective of this study is to clarify how male bodies contribute to the construction of gender-differentiated spaces by investigating the representation of tobacco advertisements in Japan.In Japan, smoking is primarily a male behavior; the smoking rate for men is about 47%, whereas that for women is about 12%. This is because Japanese tobacco advertisements tend to represent male bodies and their spaces around them.This study uses Japanese tobacco advertisements in Japanese magazines during 1987-2000. Surveying these advertisements, the following five characteristics were more significantly associated with represented male bodies than with female bodies.First, male bodies are represented with natural scenery whereas female bodies are represented in artificial environments. This implies that male bodies are intended to challenge nature. The images also emphasize the vastness of their space.Second, male bodies are represented with few words, while female bodies are accompanied by many words. This means that male space is emphasized by quiet, dignified male bodies through the elimination of words.Third, male bodies are accompanied by women's eyes. This representation of women gazing deeply at smoking men leads to the acknowledgement of male smoking space. This also means that male space is supported by female bodies.Fourth, male bodies are represented with the gesture of exhaling smoke, whereas such representation of female bodies is controlled. This difference indicates that only males are allowed to control their space by breathing out smoke.Fifth, male bodies are represented with distance between each other, contrary to women's bodies. Male relationships are defined only by their work, women, and smoking in order to bridge the distance.In conclusion, Japanese tobacco advertisements represent male bodies and contribute to the construction of male space as well as suggesting how men's personal space is associated with the wide open spaces. On the other hand, this finding also means the advertisements are prejudiced and biased toward men and the spaces they occupy. Therefore, it follows that we need to elucidate the meanings of "ordinary" male bodies in daily spaces.

2 0 0 0 OA 聖地的山里室生の景観の構造

- 著者

- 山口 泰代

- 出版者

- The Human Geographical Society of Japan

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.49, no.2, pp.159-174, 1997-04-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 47

- 被引用文献数

- 2 3

The aim of this paper is to clarify the characteristics of a landscape at the sacred place paying attention to landscape scenery.This aim is dealt with in humanistic geography. But, there are still many complicating problems in the process of study. Especially, the translation of the word landscape is problem: all geographers ought to use the word keikan as meaning landscape, although the landscape study with which humanistic geographer are concerned is differnt from that of other geographers. Humanistic geographers are interested in how felt landscape is looked at by a person. On the other hand, most geographers have been interested in how a landscape is made, not how it is felt. Despite these different interests in landscape study, all geographers ought to use a same word. Therefore, landscape study with which humanistic geographers are concerned often has difficulty being understood by many geographers on other fields.So, I use the term word landscape scenery as a key word in this paper. The term landscape scenery is used by landscape gardeners. A humanistic geographer's concern is how a landscape is felt when looked at by a person, so this concern is close to the gardener's. If I carelessly use the word keikan as meaning landscape, my aim may not be properly understood by many other geographers.By the way, a sacred place can in the considered by context of history or society. Indeed, it is important to consider a sacred place from such contexts. But even if the focus goes further than history or society, it may be possible that such a place attracting all human beings exists. I want to deal with such a place that has been attracting all human beings beyond history or society as sacred place.I take up Muro as a sacred place in this papaer. Muro is a village between mountains. It has attracted many people as a sacred place for 1200 years. I make a study through researching Muro's landscape scenery. By the way, landscape scenery changes according to season or weather. Therefore, I mainly focus on the form of landscape scenery in this papaer.Muro's landscape scenery is mainly formed by 3 main structures.1: Very long path that has very bad visibility.2: A basin scenery looking from a place where the field of vision suddenly opens up.3: Changing scenery when a person gradually descends to the sacred villageThis landscape structure looks like a form combin a tunnel with earthenware mortar. Moreover, this landscape scenery looks like the scenery when we go back to mother's womb, if we wish. Is it exaggerated that this landscape scenery is possibily attractive for all human beings?The way of feeling for landscape when pepole look at it may be different for each person or each time. But there may exist a landscape scenery attracting all human beings. At least, this paper may be able to suggest that Muro's landscape scenery is very attractive, and the landscape structure of Muro may apply to a landscape scenery attracting all human beings.The aim of this paper is to clarify the characteristics of landscape at a sacred place paying attention to landscape scenery in geography.

- 著者

- 中村 周作

- 出版者

- 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.45, no.2, pp.192-205, 1993

- 被引用文献数

- 2

- 著者

- 島津 俊之

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.69, no.2, pp.258-259, 2017 (Released:2017-07-07)

2 0 0 0 OA 名古屋市の陶磁器工業について

- 著者

- 三浦 総子

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.12, no.1, pp.31-50,95, 1960-02-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 38

- 被引用文献数

- 1

Since the Meiji Restoration with the advance of manufacturing techniques and the growth of markets, there have been many developments in the pottery industry new productive centers, and concentration of production and changes in production system. As a result, regional difference in production have become obvious.In the case of the pottery industry in Nagoya city, it was not a traditional center for pottery and was far from the clay deposits. Nevertheless, it became a pottery producing center at the beginning of the Meiji era and has since developed more than the traditional pottery centers since 1908; it now claims 20% of the pottery production in Japan. There are only a few large-scale factories which produce foreign-style table wares and insulators for export, but many small-scale specialized enterprises which produce export goods.Nagoya pottery centers have special characteristics which differ from the traditional centers in respect to the kind of production, size of the factories and the system of production. Finishing processors have played an important role in the development of Nagoya centers. They have bought unfinished pottery from traditional pottery centers such as Seto and Tono (eastern part of Gifu Pref.) and have decorated it to meet the demands of foreign markets.Since the Nagoya industry was managed by former farmers and marchants and not by traditional pottery-producers. They were able to subordinate traditional poducers by contracting home-industry workers and Samurai who had lost their social position. In this way, they have been able to produce and sale at a low price and have gotten control of the foreign market over more advanced countries. Nippon China Co. which is the largest pottery-producing factory in Japan has grown in just this way.Nagoya has the advantage of being a port-city and of being located near the traditional pottery centers. Other general tendencies such as Japan's developing role in world trade, and the development of transportation and manufacturing techniques have contributed to the growth of the industry in Nagoya. But, even more important is the fact that capital and labor in Nagoya have been able to work efficiently without the restraint of tradition.

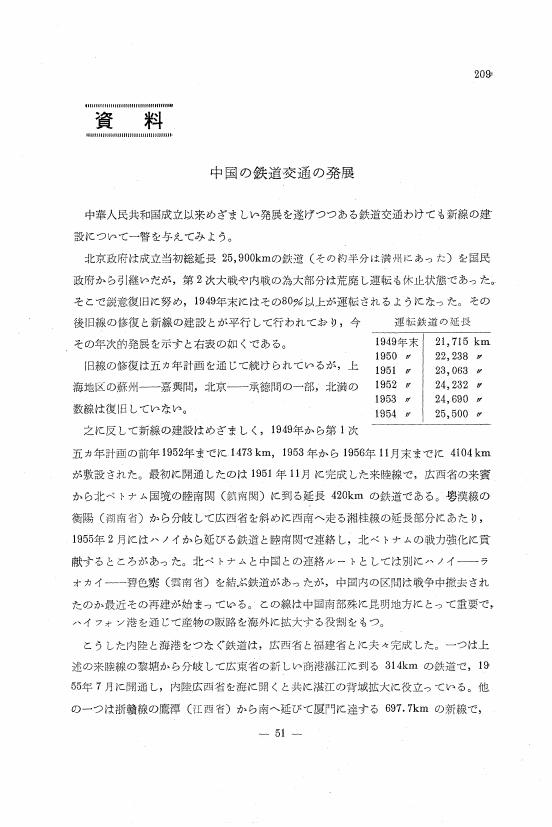

2 0 0 0 OA 中国の鉄道交通の発展

- 著者

- 海野 一隆

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.9, no.3, pp.209-212, 1957-08-30 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 2

2 0 0 0 工業化過程におけるインナーシティの形成と発展:大阪の分析を通じて

The object of this paper is to clarify how the residential areas in large Japanese city, Osaka, developed their own distinctive characteristics in the course of industrialisation. The study covers the modern period from the Meiji Restoration (1860's) to the beginning of the Showa Era (late 1920's to 1930's). The built-up area in this period exactly corresponds to the present-day inner city area. This paper also examines how and why the problems relating to the present inner city such as economic decline, physical decay and social disadvantage appeared in the industrialisation process since the Meiji Era. The author holds the following viewpoints: First, most of the emerging factory workers are assumed to be members of lower class society. Secondly, the poorer areas, which later became the inner city area, were created through the inflows of above mentioned factory workers in the course of industrialisation. Therefore the formation of lower class residential areas provides the key factor for the study of inner city problems in Osaka. Study of the labor market are used in clarifying social and living conditions of factory workers in the course of industrialisation. So the author deals with the changing process of labor markets as the analytical tool and focuses on the level of laborers' daily lives. The inadequacies of the existing Anglo-Saxon models to the areal structure of the Japanese city are pointed out, since the Japanese urban residential expansion can only be understood by taking into consideration the peculiar characteristics of the Japanese modernisation process.The results obtained are as follows: The expansion of residential areas up to the beginning of World War I characterised mainly by the outward extension of the lower class residential areas that included most of the laborers working in the cotton textile industries, heavy industry and the miscellaneous industries. The labor markets in each industry were organised differently in this development. These laborers, however, all belonged to the essentially the same class, with no appreciable income or living standard differences among industries. The organisation of residential structure consistently reflected the periphery-lower class structure proposed by Sjoberg. After World War I, the following two new factors emerged: The first is the rapid increase of white collar office workers. The second is that of a growing distinction in standard of living as well as income among members of the former lower class society, i.e., between large heavy industry workers and other factory workers. These new two factors contributed to the transformation of residential structure independently of the existing structure. The most important development was the creation of new residential areas. In this stage three types of residential area were clearly observed. The first and dominant were lower class residential areas which surrounded the city center and extended outward, building up sparse areas among some flophouse districts even at this time. This area was also characterised by the progress of the slum clearance, appearance of Korean residential districts and real advent of social policies. The second type of residential area was that of the better-off factory workers, which was formed adjacent to the factories' sites. However, this type of residential area was distributed sporadically within the first type of residential area. Between them, there were found no appreciable distinctions of housing and living conditions. The third type was white collar office workers' residential areas, which were created beyond the lower class ones and restricted to the upland lying to the south-east of Osaka City. These areas were created independently of periphery-lower class structure, which had been the most dominant or sole areal differentiation up to this time.

2 0 0 0 OA 大阪都市圏におけるインナーシティの住宅問題

- 著者

- 高山 正樹

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.34, no.1, pp.53-68, 1982-02-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 66

- 被引用文献数

- 2

Despite its high income standards, Japan's housing quality is generally inferior to international standards. This is especially true in the metropolitan regions of Tokyo and Osaka, where the structure of the inner city economic system has created very serious housing problems, especially in the form of superannuated houses, and extensive vacant housing stock.This paper examines the development of inner city housing problems in the Osaka metropolitan region. Section one presents a historical analysis of these problems. Section two outlines the intricacies of the contempory problems, related to both general aspects of urban society, and specific physical aspects of housing provision. Section three is a discussion of the housing problem in relation to specific problems of the inner city. Section four analyses some official housing statistics for the Osaka metropolitan region.The major issues of this article are as follows:1) In recent years, urban residential lots have been increasingly subdivided, with many small houses built in the conjested inner area. In comparison to houses built on wider residential lots, these small houses become superannuated rapidly. In addition, they have contributed to a generally uncomfortable residential environment.2) Most of these small houses are private rental units, containing poor and limited facilities. To escape these conditions, there has been a large outflow from the central city to the suburban areas, leaving behind a large number of vacant houses that cannot easily be re-rented.3) Most of the people remaining in these private rental units earn low incomes, yet they pay a high rent in proportion to their total incomes. The housing problem is especially acute for these people.

2 0 0 0 OA 都市の影響と空間の非連続

- 著者

- 青木 伸好

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.32, no.1, pp.1-22, 1980-02-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 37

- 被引用文献数

- 3 1

A city exerts influences on its surrounding areas, but its effects are discontinuously produced. They are chiefly due to the situation of the surrounding areas. The author attempted to analyze this discontinuous urbanization in a case of Osaka and its surrounding areas, during Japan's industrial revolution, from the late Meiji to the early Showa eras. Osaka is the city where the modern industry developed earliest in Japan. But, since the Edo era, rural cotton industry was prosperous in its surrounding areas, especially both in Kawachi, the district to the east and in Izumi, the district to the south of Osaka. At that time it was more prosperous in Kawachi than in Izumi. But in the Meiji era, the cotton industry developed more in Izumi.In this period Osaka was not yet big enough to exert a strong infuluence on the surrounding areas. Economically Osaka had a close connection with towns in the surrounding areas. As towns developed earlier in Izumi, the district had a closer connection with Osaka. By establishing connection with Osaka, Izumi could develop cotton industry earlier than other areas.Though Kawachi is situated nearer to Osaka, few towns sprang up there and it could not establish a close connection with Osaka. And so the industrial growth there was much hindered. Besides in Kawachi agricultural growth was also retarded. In the Meiji era Kawachi was behind Izumi in view of economic development.But in the Taisho era, on account of the urban growth of Osaka, industrialization and urbanization were greatly advanced in its surrounding areas. This urbanization through expansion of urbanized areas does not matter whether many towns developed or not in the surrounding areas. Urbanization of Kawachi was one of this sort. Being situated nearer to Osaka, the number of commuters to Osaka increased in Kawachi since the Taisho era, and the industry began to develop there. On the other hand urbanization of this type was only faintly progressed in Izumi. The nature of urbanization of these two districts was different. The industrialization and urbanization were more developed in Kawachi than in Izumi. Kawachi economically reversed Izumi at this time.The inversion, in other words the discontinuous urbanization, of Izumi and Kawachi depends on strength of influence of Osaka on the surrounding areas and on the different regional situation in the neighboring districts.

2 0 0 0 OA 北陸地方における都市のイメージとその地域的背景

- 著者

- 伊藤 悟

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.46, no.4, pp.353-371, 1994-08-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 38

- 被引用文献数

- 3 2

The purpose of this study is to clarify the image and its regional background of cities in the Hokuriku District, Central Japan. The methodological framework consists of three preparatory questionnaire surveys, semantic differential (SD) method combined with direct factor analysis, and step-wise multiple regression analysis.Through the preparatory surveys, 18 municipalities (shi) were selected for the analysis as well-known Hokuriku cites in the Niigata, Toyama, Ishikawa and Fukui Prefectures, and 12 pairs of bipolar adjective words were gathered as the rating scales of the image evaluation in the questionnaire of the SD method. Undergraduate students of Kanazawa University located in Kanazawa-shi, Ishikawa Prefecture are the subject for the SD questionnaire, as well as the three preparatory ones.In order to extract the dimension of the city image, the evaluation data derived from the SD questionnaire was subjected to the factor analysis by the direct method, which does not standardize the data and thus starts with the cross-product matrix. Step-wise regression analysis was also utilized for searching the regional characteristics for the backgrounds of the image dimensions in the Hokuriku cities.As a result, three image dimensions were obtained. The first can be interpreted as 'yearning' for city since it is concerned with the adjectives 'urban' and 'lively'. Commercial activity and population size affect this dimension. In the Hokuriku cities, the most desired cities are Niigata-shi and Kanazawa-shi, where commercial activities have been highly concentrated and the population are largest.The second dimension is interpreted as psychological distance, or imaginary 'separation' for city. Real distance to a city increases this separation, and the population size of the city decreases it. The third is 'hesitation', which arises for far distant and industrial or transportation cities. On the other hand, the hesitation is less for Kanazawa-shi, the nearest city for the students, and Wajima-shi and Kaga-shi, which are tourist and spa resort places.

2 0 0 0 変分原理にもとづく富士山登山道の分析

- 著者

- 平野 昌繁

- 出版者

- 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.35, no.5, pp.454-464, 1983

The variation principle is a concept for investigating the spatial pattern of any path on a given curved surface. From this point of view, properties of the Mt. Fuji climbing route are discussed, based on morphometric data. The route goes straight towards the summit on the gentle slope at the foot of the mountain, and shows a zigzag pattern on the steep slope near the summit.The variation principle maintains that the route can be a stationary one which minimizes some quantity. The straight portion of the route near the foot is the geodesic on a conical mountain, which gives the shortest distance to the summit. In order to explain the zigzag pattern near the summit, however, the amount of energy required to climb the mountain has to be taken into account. From this point of view, two types of models, namely, the excess energy model and the total energy model are possible, among which the latter seems better.If the latter model is employed, it is reasonable to assume that the energy required is proportional to the reciprocal of the power function of cosine of the slope. The exponent of the power function here is approximately 12. The zigzag route in this case has been designed so that the route needs 1.6 times as much energy as on a flat surface. The portion of the climbing route higher than 3200m in elevation is less steep, and this may correspond to the lower oxygen content above this level.

- 著者

- 丸山 浩明 仁平 尊明

- 出版者

- 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.59, no.1, pp.30-43, 2007

Buildings are moulded by and reflect order, social relations and ideas. However, how people build not only results from but also exerts influences upon how they think: order, social relations and ideas find expressions in actual buildings.As a message any building has to be decoded by those who use or observe it. But while it is composed of a multiplicity of signs, it also invites a plurality of readings and meanings. It must thus be considered on the basis of whose beliefs or whose view of the world a particular reading and meaning circulated in society is made up.The powerful in society often bring up unintentionaly as well as deliberately a certain reading and meaning of a building. Rather, the dominant are those who manage to present them that may be taken in as unquestioned and thus "natural". Buildings are major arenas where reading and meaning publicly unfold.The material of my discussion is the Taman Mini Indonesia Indah (Beautiful Indonesia in Miniature Park), popularly known as Taman Mini, located in a suburb of Jakarta, the capital city of Indonesia. It is both a recreation park and a cultural theme park containing examples of traditional architecture, museums, religious buildings, movie theaters, gardens, and other cultural and historical exhibitions and facilities alike. It is designed to provide visitors with an overall insight into Indonesia's people, arts, social customs, history and living environment.My purpose is to reveal the use of the Taman Mini by investigating its design, location and way of representing, considering the socio-political setting of which it is a part. Both in the selectivity of its content and in the signs and style of representation the Taman Mini works to support the order favorable to those who have built it.In November, 1971, when the government was shifting to pro-capitalistic development policies, the President's wife first announced an idea to build a museum-park complex aiming at making Indonesia known to international tourists and raising national consciousness. A few years before, the republic saw the most crucial time in its post-colonial history. Late on the evening of 30 September 1965, army units launched a limited coup in Jakarta ostensibly to remove a group of generals said to be plotting against the then (and first) president. They killed six leading generals, the corpses of whom were later discovered in a well near the present site of the Taman Mini. The coup was crushed in twenty-four hours by special forces commanded by Major General Suharto. These events laid basis for a gradual seizure of power by him and the installation of the so-called New Order.Mrs Suharto's idea immediately came under attack by intellectuals and students, for being for her prestige and a waste of domestic funds, and for the compulsory clearing of small-holder farmlands at the site at a low rate of compensation. She insisted on fighting for her project and declared it was of service to the people to deepen their love for the fatherland. At last the President uttered a statement affirming his full back-up to his wife's project. Construction of the vast park began in 1972, and the opening by the President occurred on April 20, 1975.Some facilities and exhibitions of the Taman Mini are precise replicas with more perfection than their originals. Others are drained from immediate functions and actual life by being replanted regardless of the backgrounds on which they should be. They are all signs of"Indonesian-ness", and the Park serves as a sketch map showing in public space how Indonesia is organized.The Taman Mini conveys a set of values. The juxtaposition of provincial architectures, houses of worship, folk ways of life, handicrafts, and performing arts visualize the cultural diversity and relativism of Indonesian society.

2 0 0 0 OA 地図化能力の発達に関する一考察

- 著者

- 鈴木 晃志郎

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 人文地理学会

- 雑誌

- 人文地理 (ISSN:00187216)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.52, no.4, pp.385-399, 2000-08-28 (Released:2009-04-28)

- 参考文献数

- 80

- 被引用文献数

- 1 2

This paper summarizes the debate between Blaut and Downs (and his collaborator, Liben) concerning the development of mapping abilities of young children.Jean Piaget's theory of cognitive development has been one of the most influential theories in the field of cognitive mapping research. Two essential elements of Piaget's theory regarding the developmental sequence of spatial abilities with age are nativism and constructivism. A forum in the Annals of the Association of American Geographers journal in 1997 on the mapping abilities of young children helped to distinguish the intrinsic duality of Piaget's developmental theory and its influence on the debate between Blaut and Downs/Liben.Both Blaut and Downs/Liben studied young children's ontogenetic development of mapping abilities, but they examined different aspects of Piaget's theory. On the basis of nativism, Blaut recognized that children can perform various mapping tasks regardless of age, and he insisted that children naturally possess mapping abilities, whereas Piaget implied that they could not. In contrast, on the basis of constructivism, Downs and his colleagues emphasized that children's mapping abilities are the effect of both direct and indirect learning experience, and they pointed out some deficiencies in Blaut's testing method.In spite of their contrasting standpoints, both researchers were influenced by Piaget's theories, but emphasized different aspects of the complex process of cognitive mapping development.

2 0 0 0 神戸における白系ロシア人社会の生成と衰退

More than two million Russian refugees resulted from the Russian Revolution in 1917. These refugees were termed "White Russians" ("Hakkei-Roshiajin" in Japanese) and did not accept the Soviet regime. For this reason, they escaped from their motherland and spread to many countries similar to a diaspora.The purpose of this paper is to discuss the way of life and the functions of White Russian society who chose Kobe, a former central city of White Russians living in Japan, as their domicile. This study is based on documents from the Diplomatic Record Office of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and oral data gained through fact-finding visits and interviews in the area.Most White Russians in Japan lived in Tokyo and Yokohama before the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923. However, a large number of them migrated from the Tokyo area to Kobe, which provided shelter from the disaster. Thereafter, Kobe became one of the central settlements of White Russians in Japan, along with the Tokyo metropolitan area. In those days, many White Russians, more than 400 people at its highest point, settled in Kobe, particularly in the former Fukiai and Ikuta wards.The term "White Russians" refers to all people from the territory of the Russian Empire, including Christians, Jews, and Muslim Tatars. Therefore, White Russians are a group that is diverse in terms of culture, ethnicity and religion. Consequently, their organizations were based on their religious affiliations in Kobe.In the period after 1925, White Russians were categorized as stateless in Japan. They had the right to obtain a "Nansen Passport", issued by the League of Nations as identification cards, but their status was very uncertain. Moreover, many White Russians were peddlers and frequently travelled around. As a result, the Japanese authorities watched them closely as they were suspicious that White Russians were spies sent from foreign countries, especially from the Soviet Union. In fact, some White Russians were expelled from Japan in the 1920s. However, in the 1930s, chauvinistic nationalism arose among White Russians themselves, and some of them even provided donations to the Japanese government and army. This indicates that the White Russian society was subsumed within Japanese society in those days. In addition, there was some conflict over the attitude toward the Soviet Union in White Russian society.After W. W. II, the number of White Russians in Japan suddenly decreased. This is because many people went abroad in order to avoid chaos after the war. In Kobe, there was also a rapid decrease in the population of White Russians, and their organizations gradually declined and eventually dissolved. Today, only "The Kobe Eastern Orthodox Church Assumption of the Blessed Virgin", "The Kobe Muslim Mosque", and "The Kobe Foreign Cemetery" remain in Kobe as remnants of former White Russian society.These cases illustrate the disappearance of the ethnicity of White Russians in Kobe. There is a tendency for refugees to remigrate or for their families to disperse. Many White Russians were no exception, and this tendency is one of the reasons why White Russians disappeared from Kobe. In addition, the negative attitude of the Japanese state towards the inflow and settlement of foreigners is one of the major factors explaining their disappearance.