3 0 0 0 OA 歴史認識をめぐる日本外交 ―日中関係を中心として―

- 著者

- 庄司 潤一郎

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2012, no.170, pp.170_125-170_140, 2012-10-25 (Released:2014-10-26)

- 参考文献数

- 73

It is often the case that when economic ties expand through trade, and the exchange of people expands, diplomacy will also take a favorable turn. However, in terms of the Japan-China relationship, which is symbolized by “cold political relations but hot economical relations,” such progress is not occurring. Because of incidents such as the collision of fishing boats off the coast of the Senkaku Islands, political tensions do not seem to be withering. Both Japan and China admit that the reason for this is the existence of the historical perception issue. However, until the 1970s, the historical perception issue was a domestic Japanese issue rather than a pending problem between Japan and China; but in 1982, with the textbook incident, it became an international issue. During this process, both the Japanese and Chinese governments have made certain political “compromises,” but this has instead stimulated domestic radical claims and both nations strengthening their nationalism, and this has created the structure of a vicious cycle. Furthermore, in the background, a composition was made involving the “politicization” of the historical perceptions of both countries and the “asymmetry” of respecting Chinese claims. Moreover, in recent years, the downturn of Japan and the rise of China have been making the historical perception issue more complex. In other words, the historical situation that Japan and China have never experienced coexistence as great powers, has been promoting a sense of mutual rivalry,which has undeniably led to the historical perception issue becoming more complicated. The historical perception issue has become a complex phenomenon as a result of its expansion in both countries after the textbook incident, such that the issue spans several dimensions of political diplomacy, academic research,and national sentiment; and it is becoming difficult to discuss it only within the framework of each government’s diplomacy. Therefore, it is necessary to work on the historical perception issue not only by considering diplomacy,but also by keeping watch on the achievements of academic research and on public opinion in both countries.

3 0 0 0 OA イギリス外交における文化的プロパガンダの考察、一九〇八―一九五六年

- 著者

- 松本 佐保

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2013, no.173, pp.173_112-173_126, 2013-06-25 (Released:2015-06-09)

- 参考文献数

- 62

Cultural diplomacy and cultural propaganda have been discussed by some scholars of British diplomatic history, but it is not clear what degree of influence these activities had upon the mainstream of diplomacy. This article attempts to explore the importance of cultural diplomacy for Britain in the first half of the twentieth century, including the world wars, by looking at the cases of British policy towards Italy and the United States. It begins by looking at Sir James Rennell Rodd, the British ambassador to Italy between 1908 and1919, who used his cultural diplomacy in order to persuade Italy to join the Allied side during the First World War. He helped to create the British Institute in Florence, which in 1917 came under the Ministry of Information (MOI) as part of the British propaganda effort. Once the war ended the MOI was dissolved, partly because the Foreign Office disliked its aggressive propaganda activities towards foreign countries. However, when it became apparent that Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, which were more advanced in the field of political and cultural propaganda, were using cultural diplomacy to increase their influence in the world, the Foreign Office reluctantly had to organize some form of propaganda to counter their activities. This led to the establishment of the British Council in 1934, which was, in part, loosely modeled upon the British Institute in Florence. It attempted to concentrate upon purely cultural activities, but with another war approaching this line was breached and the Director, Lord Lloyd, increasingly used the Council for political propaganda and intelligence-gathering. The greatest challenge came in the United States where British propaganda had to avoid the excesses of the First World War and yet still promote Britain`s cause. In this environment the Council`s cultural propaganda became useful by emphasizing the common ethnic and cultural roots of the two countries. In addition, the Council proved useful in the post-war period as its activities could be used to promote democratic values and thus encourage other countries, such as Italy and Greece, to move away from both fascism and communism. This article therefore demonstrates the importance of cultural diplomacy and how it contributed to the mainstream of British diplomacy.

3 0 0 0 OA 韓国政治指導者の合理的選択としての対日敵対行動

- 著者

- 籠谷 公司 木村 幹

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2015, no.181, pp.181_103-181_114, 2015-09-30 (Released:2016-06-08)

- 参考文献数

- 33

Since the end of World War II, historical legacy has caused a series of disputes between Japan and South Korea. Scholars attribute these repeated disputes to Japan’s failure to settle the compensation problem, American foreign policy toward Japan in the early period of the Cold War, the unequal distribution of national capabilities between Japan and South Korea during the Cold War, and the particularities of nationalism in both countries. The literature emphasizes the peculiarities in the Japan-South Korea disputes. However, this does not mean that we are not able to explain the Japan-South Korea disputes in a systematic manner. For example, Kagotani, Kimura, and Weber (2014) argue that South Korean leaders are more likely to initiate a political dispute with Japan in order to divert public attention from economic turmoil to Japan-South Korea disputes. What else drives South Korean leaders to start a political dispute with Japan? In this article, we focus on South Korean leaders’ motives and policy alternatives to explain how a trade dispute evolves into a political dispute between Japan and South Korea. We assume that a South Korean president is a policy-oriented actor and prefers to take a soft line toward Japan to manage Japan-South Korea relationships. The president also needs political support from the legislature in order to implement public policy. As the presidential approval rate declines, a candidate for the next president tends to behave as a hard-liner to attract public attention, and the legislature follows the candidate, not the president. To implement good public policy, the president is required to maintain his/her popularity and take a hard line. Given such political constraints, we examine the president’s choice. When the president faces a large trade deficit, he prefers to start a trade negotiation with Japan, not to initiate a political dispute to divert public attention. Only if the negotiation fails, the president initiates a political dispute by addressing historical legacy because issue-linkage can induce mutual concessions, and because even a concession in the political dispute, not the trade dispute, can help the president maintain his/her popularity in order to move back to a soft-line in the subsequent periods. Thus, the president often engages in this diversionary tactic and a trade dispute often evolves into a political dispute. We test whether a trade deficit is more likely to induce more South Korean hostile actions toward Japan. The statistical analysis using the event data confirms that trade imbalance favoring Japan often causes a political dispute regarding historical legacy. The case studies of Presidents Rho Tae-woo and Kim Young-sam reveal political decisions behind the escalation of Japan-South Korean disputes.

3 0 0 0 中華民国の公定歴史認識と政治外交――一九五〇―一九七五年

- 著者

- 深串 徹

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2017, no.187, pp.187_46-187_61, 2017

<p>How to commemorate the Sino-Japanese war is a controversial issue in contemporary Taiwan. The government of the Republic of China (R. O. C.) often commemorates the war from legitimate Chinese government's point of view, whereas some Taiwanese scholars criticize it as ignoring the memories of the majority of Taiwanese people. As a result, scholarly attention in Taiwan has gradually been shifting to explore the memories of "ordinary" Taiwanese people during the war. At the same time, not enough attention is being paid to the concrete contents of the official memory of the war and how it was created. In particular, scholars are holding different images as to whether the official historical narrative of the war during Chiang Kai-shek period (1950–1975) could be recognized as containing "anti-Japanese" sentiment or not. The major factor for these divisions is lack of clear definition and indicators of what constitutes "anti-Japanese" sentiment.</p><p>This article defines the historical narrative that contains "anti-Japanese" sentiment as follows: If, in a certain period of time, a government claims that the reason why she is being cautious of Japan comes from its past adversarial relationship with her, that narrative could be characterized as containing "anti-Japanese" sentiment. As for the indicators, this paper establishes four criteria: 1) Was the war against Japan described as the most important fight in the R. O. C.'s history? 2) How strongly did the R. O. C. government stress its victimhood in the war? 3) Was reconciliation with Japan described as being done sufficiently? 4) When the R.O.C. had diplomatic conflict with Japan, did the government provoke Taiwanese people to remember the memory of war?</p><p>Using these definitions and indicators, this paper examines the R. O. C. government's official historical narrative of Sino-Japanese war during Chiang Kai-shek administration. The author argues that when there was diplomatic relations with Japan, the R. O. C.'s official narrative of war had a conciliatory tone toward Japan. While provoking hostile feeling against the Chinese Communist party in mainland to fight a civil war, the R. O. C. formed and used the memory of the Sino- Japanese war to promote its relations with Japan in order to consolidate anti-communist camp in East Asia. Therefore, during that period, the official historical narrative was hard to estimate as "anti-Japanese".</p><p>However, after the R. O. C. broke off its diplomatic relations with Japan, in response to latter's normalization of relations with the People's Republic of China, the reconciliation with Japan was described as null and void because of destruction of peace treaty between the R. O. C. and Japan. Shortly afterwards, the narrative of victimization in the war grew stronger in the official discourse of the R. O. C., the historical narrative started to contain "anti-Japanese" sentiment.</p>

3 0 0 0 OA 白豪政策の成立と日本の対応 -近代オーストラリアの対日基本政策-

- 著者

- 竹田 いさみ

- 出版者

- JAPAN ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1981, no.68, pp.23-43,L2, 1981-08-30 (Released:2010-09-01)

- 参考文献数

- 133

The Barton government, the first federal government in Australia in 1901, refused to meet the Japanese demands that Japan should be exempted from the White Australia Policy. There was a vicious circle that the Japanese protest made the policy more anti-Japanese and this upset Japan immensely, since it put the prestige of Japan at stake. For Australia, there were several reasons not to negotiate with Japan over the immigration questions. Firstly, the New South Wales colonial legislation of immigration restriction, fundamentally the same as the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act, was approved by Takaaki Kato, Japan's minister in London; hence, the Japanese protest in 1901 was contradictory to Kato's approval. Secondly, the Barton government finally passed the act after adjusting the different interests of the political parties and the British Colonial Office so that they would be in harmony with each other. To complete the legislation, Barton found Japan's demands difficult to meet. Thirdly, Barton found Great Britain as a lever to solve the Japanese questions.From 1894 to 1901, the Australian attitude toward Japan was primarily to promote trade but not to allow Japanese migrants to Australia. The Queensland's Nelson government's adhesion to the 1894 Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Commerce and Navigation promising the freedom of entry into the contracting parties, caused the federalist government to legislate the Unified Federal Act which excluded Asians. Nippon Yusen Kaisha's steamship service between Japan and Australia, even though contributing to increased trade, was regarded cautiously since it encouraged Japanese migrants to Australia. There was mainly no military consideration on the Japanese immigration questions. It was after the Russo-Japanese War that Australia considered Japan as a military threat.

3 0 0 0 OA 「引き留められた帝国」としての英国

- 著者

- 篠崎 正郎

- 出版者

- JAPAN ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2011, no.164, pp.164_29-42, 2011-02-20 (Released:2013-05-22)

- 参考文献数

- 85

It is widely believed that the United Kingdom had decided to retreat from “East of Suez” in January 1968. It planned to withdraw all its forces stationed in South-Eastern Asia and Middle East by the end of 1971. However, the next Heath government made a small change in this policy, left some forces in the area and maintained military commitment beyond 1971. These forces were finally withdrawn by Harold Wilson who was back in power in March 1974. Few studies, however, mention the British forces in the “East of Suez” after 1968. This thesis clarifies the detail and the logic through the policy of retrenchment from 1974 to 1975.The Conservative government decided to maintain military commitment in the “East of Suez.” First, there were still lots of British bases in South-Eastern Asia, Indian Ocean and Middle East though the force level was reduced. Second, the United Kingdom retained the general capability which would be available to be deployed outside Europe. Finally, there were regional organisations like CENTO or FPDA (Five Power Defence Arrangements) which enabled the United Kingdom to cooperate with the local countries.However, the British economy in the 1970s could not support these commitments. Roy Mason, the Secretary of State for Defence in the Labour government, began the Defence Review as soon as he entered office. The principal object of the Review was to reduce defence budget from 5.5% to 4.5% of GNP in the next 10 years. The non-NATO commitments were preferred to be cut since the British government tried to concentrate its defence efforts in the NATO area. In addition, he also decided to abandon the reinforcement capabilities outside NATO.The Defence Review was so drastic that it needed consultation with allies. However, the negotiations were not easy. Most countries tried to keep the British forces in the “East of Suez” because they recognised the importance of the British presence. The United States was concerned about the abandonment of intervention capability outside NATO and desired the British presence in the Mediterranean. As a result, the British government compromised with some of these demands and decided to stay in some areas. Apart from this concession, the British government could carry out the withdrawal as it originally planned.This study indicates the British aspect as an “Empire detained”. British departure was regretted not only by the United States but also by the Commonwealth countries. Britain's retreat from the Commonwealth marks the transformation of British external policy from the world to the Atlantic community.

3 0 0 0 OA イラク政治におけるジェンダー-国家、草命、イスラーム-

- 著者

- 酒井 啓子

- 出版者

- JAPAN ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2007, no.149, pp.30-45,L7, 2007-11-28 (Released:2010-09-01)

- 参考文献数

- 39

- 被引用文献数

- 1

Women in Iraq have been always at the “periphery” of the multi-layered centre/periphery structures. They were located at the periphery of the traditional Muslim/Arab society in a Western/modernist sense. Iraq itself, on the other hand, is located at the periphery of the colonial and global economic system. Consequently, Iraqi women have found themselves in a double peripheral position, both at the international as well as the domestic level.The leftist political elites who became dominant in Iraq after 1958 understood the liberation of women as evidence of the progressiveness of modern society, as they opposed both feudalism and Western colonialism. The state under the Ba'thist regime in the 1970s controlled women's organizations and included them in the system of revolutionary mobilization. State control was strengthened during the war period in the 1980s as a means to mobilise women into the labour force.The leftist regimes in Iraq pursued this secular and de-Islamisation policy until after the Gulf war, but in the 1990s Saddam Hussein introduced a re-tribalisation and re-Islamisation policy as a means to compensate for the state's lack of ability to govern local society. This revival of traditional Muslim and tribal social systems drove women again to the periphery.The US invasion of Iraq and the removal of Saddam's regime has led to a change in the previous central/peripheral relationship. Iraq was placed at the periphery of the world political system under US/UK control. At the same time, the new Iraq regime, established following the general election in 2005, is led by Islamist political parties, which were in a peripheral/outlaw position in Iraq before 2003. Under this new situation, women have been divided into three categories. First, there is a group who utilise the US/Western support to “liberate/democratise” Iraq and demand the introduction of a Western legal and social system to protect women's rights. A second group accepts the newly introduced Western electoral system but not the Western-type equal political rights for women. The third are women members of Islamist political parties, who act as a part of the revolutionary forces pursuing the establishment of an Islamic state.Under both the leftist and Islamist regimes, revolutionaries have consistently pursued their own goal of “liberating” their nation from the rule of the “centre” of world politics, which is led by the Western system; sometimes they play up the nominal status of women to the state elites, but in other cases pursue their own aims at the expense of women's rights.

3 0 0 0 対比賠償交渉の立役者たち:日本外交の非正式チャンネル

- 著者

- 吉川 洋子

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1983, no.75, pp.130-149,L13, 1983

Japanese-Philippine negotiations on war reparations lasted from 1951 through 1956, often interrupted by disagreements on the terms of payment. Significantly, the diplomatic deadlocks were often broken by informal channels of communications and secret talks. A host of political and business leaders who had varying degrees of interests in each other's country participated.<br>A most important breakthrough in deadlocked talks was made in New York and Washington in November 1954 by Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru and Senator Jose P. Laurel, whose secret meetings were arranged by the Premier's confidants on Philippine affairs, Nagano Mamoru and Shiohara Tamotsu. Nagano, a leading steel industrialist, had business interests in the Philippine iron mines and other resources, and had his own proposal on a variety of development projects to be financed by reparation funds. Shiohara, Executive Director of the Philippine Society of Japan, had been a personal friend of Senator Laurel since the Japanese occupation period when Laurel was President of the Republic and Shiohara served his government as an advisor on internal affairs.<br>Nagano played several other roles during the whole process, including one as a member of the Japanese delegation for reparations talks. So did many other leaders such as former Ambassador Murata Shozo, Minister Takasaki Tatsunosuke, Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke, Foreign Minister Fujiyama Aiichiro, and businessmen like Furukawa Yoshizo who had lived in the Philippines before the war and claimed to be experts about the country.<br>Another diplomatic breakthrough was achieved in May 1955 by Ferino Neri, chief Philippine reparations negotiator, who ran a series of secret meetings in Tokyo with political and business influentials regarding the terms of payment. He finally obtained Prime Minister Hatoyama's confidential endorsement of his proposed terms. This success was made with the skillful help of Hatoyama's Deputy Cabinet Secretary Matsumoto Takizo, who apparently had many Philippine acquaintances primarily through the Free Masonry whose members pointedly included Hatoyama, Senator Camilo Osias, and most probably Senator Laurel.<br>The long negotiations demonstrated the significant roles played by informal contact-makers on both sides. Many of them were those with official capacity seeking secret contacts, but some without official capacity also volunteered secretly to help the talks. Both Japanese and Philippine political cultures weigh personal ties, particularly, ties based on clientelism, in political dealings. The interaction of the two cultures over such difficult negotiations multiplied the effectiveness of informal contact-makers.

3 0 0 0 OA 核実験問題と日米関係-「教育」過程の生成と崩壊を中心に-

- 著者

- 樋口 敏広

- 出版者

- JAPAN ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2003, no.134, pp.103-120,L14, 2003-11-29 (Released:2010-09-01)

- 参考文献数

- 66

The Bikini incident of 1954, ushering in a new era of atomic plenty, aggravated nuclear fear and a danger of neutralism among the Japanese public. This article examines how the Japanese and U. S. governments tackled a problem of antinuclear sentiment which emerged as a hotbed for neutralism in 1954-1957. Focusing on a unique nature of Japanese antinuclear sentiment as a form of nationalism, this article sheds light upon a role of diplomacy as a communication tool to address antinuclear sentiment and nationalism.This study argues that the Yoshida administration succeeded in settling an immediate problem of the Bikini incident but failed to address the question of nationalism deeply rooted in spreading antinuclear sentiment among the public. Worried about a weak leadership of the Japanese conservative government, the Eisenhower administration could not simply overlook this failure. Then it tried to directly confront the growing antinuclear sentiment through a coordinated public relations diplomacy it regarded as “education.” With “education, ” it intended to lead Japan to embrace continued nuclear-testing. This “education” failed, however, when Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi embarked upon anti-nuclear-testing diplomacy. By positively responding to the growing nationalism embedded in the antinuclear sentiment, Kishi thought, he could win popularity for pro-American conservative LDP and therefore contain a danger of neutralism. Containment of neutralism was, ironically, exactly what the Eisenhower administration had envisaged. Kishi's diplomacy, therefore, shared the goal with U. S. educational efforts, but adopted a different approach. His diplomacy finally nullified “education, ” which raised a voice inside the Eisenhower administration calling for changing U .S. policy on nuclear testing rather than changing Japan through “education.” The eventual course of antinuclear nationalism in U. S. -Japan relations once again remained to be seen.

3 0 0 0 OA 国際関係論と地域研究の狭間

- 著者

- 浅羽 祐樹

- 出版者

- JAPAN ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2008, no.151, pp.156-169, 2008-03-15 (Released:2010-09-01)

- 参考文献数

- 41

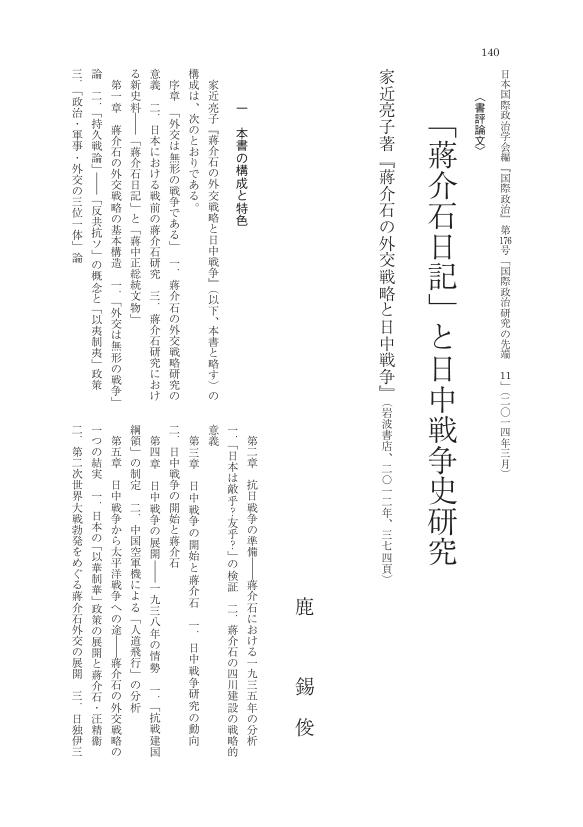

3 0 0 0 OA 「蔣介石日記」と日中戦争史研究

- 著者

- 鹿 錫俊

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2014, no.176, pp.176_140-176_151, 2014-03-31 (Released:2015-10-20)

- 参考文献数

- 17

3 0 0 0 OA 徳永昌弘著『二〇世紀ロシアの開発と環境』(北海道大学出版会、二〇一四年、三三八頁)

- 著者

- 臼井 陽一郎

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2015, no.179, pp.179_163-179_166, 2015-02-15 (Released:2016-01-23)

3 0 0 0 OA フランスにおけるアルジェリアに関わる「記憶関連法」

- 著者

- 大嶋 えり子

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2016, no.184, pp.184_103-184_116, 2016-03-30 (Released:2016-11-22)

- 参考文献数

- 66

Recognising memories of past perpetrations or not is often an issue connected with responsibility and reconciliation between victims and perpetrators. This has been for a long time an issue vexing French authorities.In the 1990’s, French government and parliament began to recognise memories related to the colonisation and the independence war of Algeria. Although French authorities had kept silent on those dark events to which many fell victim on both sides of the Mediterranean Sea, they started to recognise memories related to Algeria by erecting memorials, opening museums and making laws.This article aims at elucidating why the French parliament made laws recognising memories related to Algeria. Making memory-related laws, called “memory laws (lois mémorielles)”, is a particular way to France to recognise certain perceptions of the past, and is different from other memory recognitions as it has a binding force.I thus considered two laws, made in respectively 1999 and 2005. The law passed in 1999, that I will call the “Algerian war law”, replaces the term “the operations in North Africa” with “the Algerian war or the battles in Tunisia and Morocco” in the French legislative lexicon. It officially recognises that the conflict in Algeria from 1954 to 1962 was a war, whereas it has been long reckoned to be a domestic operation aiming at maintaining order. The law enacted in 2005, that I will call the “repatriate law”, pays homage to former French settlers in Algeria for their achievements and emphasises the “positive role of the French presence abroad”.This study shows that those two laws were made in order to reinforce national cohesion among French people, instead of fostering dialogue between Algerians and French. By examining the wording and the law making processes of the two acts in question, especially the debates conducted at the National Assembly, it sheds light on how French elected representatives tried not to acknowledge France’s responsibility for the damages caused during the colonisation and the independence war and how they attached little importance to reconciliation with Algeria. Both laws indeed do not contain memories of Algerian people harmed under French rule, except some parts of the memory of Harkis, who fought with the French army during the war.The recognition of memories by official authorities of former perpetrators has significant repercussions and can encourage reconciliation between antagonists. It however tends to avert eyes from victims’memories in France when the past related to Algeria is in question. Issues connected with memory do not only concern relations between France and Algeria, but also involve the larger question of how to remember perpetrations caused by discriminatory policies and how to overcome them to accede to reconciliation between victims and perpetrators.

- 著者

- 山下 光

- 出版者

- JAPAN ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2014, no.175, pp.175_144-175_157, 2014

This article examines new/neo humanitarianism in a wider context of post-Cold War international relations and argues that its emergence corresponds to an important shift in the meaning of the political in today's international relations. It describes the shift in terms of the contrast between two logics of politics: the conventional "logic of distinction," whereby political processes take place between territorially separated, sovereign entities, and the newer "logic of translucency" in which new values (and risks) are generated by the actor's ability and will to extend beyond its material and ideational boundaries. The logic of translucency has been adopted by many actors who thereby aim to generate new values and extend the reach of their own activities. From this perspective, new humanitarianism, which seeks linkage to the activities that were once off limits to traditional humanitarianism (military intervention, development and governance), can be seen as another example of the ideational and practical socialization to a new political landscape. However, as political actors acting on the logic of translucency each try to extend themselves beyond their traditional realms, dilemmas, contradictions, clashes and conundrums tend to occur: the logic of translucency ironically thus generates diverse forms of "murkiness," creating in turn a new desire for translucency.<br>The current crisis in humanitarian assistance (kidnappings, killings and obstructions against humanitarian personnel) can be seen as part of the murky consequences of new humanitarianism and politics and, as such, cannot be blamed solely on the post-911 tendency of the humanitarianization of politics, i.e., the utilization by state authorities and militaries of humanitarian arguments and programs to serve their ends. This article also suggests that new humanitarianism as well as its murky consequences cannot be wished away by insisting that humanitarianism should go back to the basics, because the changing nature of humanitarianism has deeper roots in the changing nature of politics in general.

3 0 0 0 OA 権威主義体制下の単一政党優位と選挙前連合の形成

- 著者

- 今井 真士

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2013, no.172, pp.172_44-172_57, 2013-02-25 (Released:2015-03-05)

- 参考文献数

- 28

It is often assumed that, even if opposition parties can participate in electoral politics, they are fragmented, insufficient and insignificant under authoritarian regimes in which the ruling elites have maintained their political power for the long term. Recently, however, there have been not a few pre-electoral coalitions in various countries in Southeast Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, the Post-Communist World and the Middle East that opposition parties have formed with each other during the parliamentary elections. Under what conditions do opposition parties form pre-electoral coalitions in multiparty authoritarian regimes? There are still a few studies on pre-electoral coalitions under authoritarian regimes, though even such arguments have not consider a possibility that opposition parties could form them not only in competitive context but also in hegemonic one: In other words, these studies have treated a degree of party competitiveness as a given condition and dismissed a question of how it affects coalition formation among opposition parties. Therefore, this article focuses on party competition and electoral institutions, and attempts to testify their effects on the pre-electoral coalitions formed by the leading opposition parties by using an original data of the parliamentary elections from 1961 to 2008 in multiparty authoritarian regimes in which ruling elites have maintained their political power for more than a decade. The first section outlines it as a background of pre-electoral coalition formation of opposition parties that the number of authoritarian regimes which adopted a multiparty system has dramatically increased since the 1990s. Although compelling to adopt a multiparty system as a part of political liberalization, ruling parties have still tended to maintain their economic, social and political dominance and the opposition parties have tended to be in a disadvantageous position: It is authoritarian single-party dominance. The second section provides four hypotheses of pre-electoral coalitions focused on the party competition and the electoral institutions on the basis of two contrasting logics derived from the analyses of authoritarian regimes:One is that multiparty elections can facilitate their political liberalization, and another is that they can foster their political stability. The third section testifies several models with a large-N logistic regression with a sample of 248 parliamentary elections in 54 countries in the period 1961-2008. These models show that the leading opposition party is more likely to form pre-electoral coalitions with other parties when (1) the opposition parties as a whole have more seat share and when (2) the Effective Number of Opposition Parties (ENOP) increase, but that it is less likely to do it when (3) the numbers of the interaction term of seat share and ENOP increase and when (4) the plurality voting system is adopted. Finally, this article concludes by emphasizing that political institutions matter in authoritarian regimes.

3 0 0 0 岡義武『山県有朋』

- 著者

- 大山 梓

- 出版者

- JAPAN ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.6, pp.149-151, 1958

3 0 0 0 「国際貢献」に見る日本の国際関係認識:―国際関係理論再考―

- 著者

- 大山 貴稔

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2015, no.180, pp.180_1-180_16, 2015

"International contribution", diffused in the wake of Gulf War, is a peculiar idea in Japan. Western International Relations Theory (IRT) talks about "international coordination" and/or "international cooperation", but never deals with "international contribution". I'm going to focus on the idea of "international contribution", which enables me to discuss Japanese perception of international relations and encourages me to reconsider so-called IRT.How does the idea of "international contribution" rise up to the surface? The historical overview of this question is presented in the first section. Through the rapid economic growth, the prime ministers of Japan such as Eisaku Sato, Yasuhiro Nakasone and Noboru Takeshita came to feel the enhanced international status as one of big powers, which was unaccompanied by Japan's actual performance. This gap between the expectation from "international society" and the reality in "international society" provided the setting for the idea of "international contribution". The emergence of this idea was nothing more than contingent use initially. Notwithstanding this genesis, "international contribution" precisely captured something like the flavor of the time and got into circulation.Then, how was "international contribution" mentioned? The structural outline, which is visible in the use of "international contribution", is inductively extracted in the second section. The perception that Japan had taken "free ride" on "public goods" arousing international criticism keenly made Japanese realize the necessity of "international contribution". Furthermore, "international society" is hypostatized in the background of "international contribution", dredged through the comparison with "international coordination" and "international cooperation". These understanding denote that at least for most of the Japanese the realm of international relations is not "anarchy".Besides, how was "international contribution" as practice put into? Alongside of this question, transition of subject positions, especially pertaining to the Self Defense Force (SDF) and the Non-Governmental Organization (NGO), is reviewed in the third section. Although dispatching SDF which evokes the shade of military forces had long been regarded as taboo in the postwar period, the SDF brought about recognition as an actor of "international contribution" together with growing necessity of "international contribution". NGO, on the other hand, came to accumulate fund and human material due to escalating interest in "international contribution". Then the governmental awareness of NGO has gradually changed and the government has got to utilize NGOs.Various aspects of "international contribution" are sketched through the analysis of these chapters. Based on these aspects, I wonder if "international contribution" is a certain type of IRT. It functioned historically as a "lens" which gave us some "answers" at that time. If that's the case, we ought to consider what the "academic" theory is and what it should be.

3 0 0 0 OA トラウトマン工作の性格と史料 -日中戦争とドイツ外交-

- 著者

- 三宅 正樹

- 出版者

- 財団法人 日本国際政治学会

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1972, no.47, pp.33-74, 1972-12-25 (Released:2010-09-01)

- 参考文献数

- 81

- 著者

- 酒井 哲哉

- 出版者

- JAPAN ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.117, pp.121-139,L12, 1998

This essay intends to analyse the formative process of discourses on international politics in post-war Japan, and by doing so shed light on the hitherto neglected aspects of Japanese political thought. Most of previous studies have understood discourses on international politics in post-war Japan as a simple dichotomy, realism/idealism, and paid little attention to the intellectual contexts in which these discourses had their own roots; While "idealists" have searched for their identity in that Japan was reborn as a "peace-loving" nation after the end of the Pacific War, "realists" have acused the "idealists" of being naive. Both of them, however, seem to have overlooked or possibly masked from what kind of historical background discourses on international politics in post-war Japan had emerged and to what extent post-war discourses had been influenced by pre-war ones. Therefore, this essay will uncover the complicated relationship of political thought between post-war and pre-war Japan.<br>Chapter I "Morality, Power and Peace" treats how relationship between morality and power in international politics was argued during the early post-war era. Dogi-Kokka-Ron (Nation Based on Morality), the dominant discourse on peace immediately after Japan's surrender, insisted that Japan search for morality rather than power and by doing so exceed the principle of sovereignty, characterestic of modern states. In spite of its appearance, however, Dogi-Kokka-Ron contained echoes of philosophical argument of the Kyoto School which had advocated morality of Japan's wartime foreign policies vis-à-vis Western imperialism. Thus Maruyama Masao and other leading intellectuals, who belonged to the school known as Shimin-Shakai-Ha (Civil Society School), tried to differentiate their arguments from Dogi-Kokka-Ron and create another discourse on morality, power and peace. Since the Kyoto School had criticised harshly the modernity and nationalism during the Pacific War, Shimin-Shakai-Ha's undertakings resulted in reestimation of the modern nation-state. This chapter further elucidates Shimin-Shakai-Ha's ambivalent attitudes toward power and norm in international politics with special reference to its understandings of the concept of the equality of states.<br>Chapter II "Regionalism and Nationalism" focuses on Royama Masamichi's argument on regionalism. Regionalism was a difficult topic to handle during the early post-war era because it could bring to mind the idea of the Great East-Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere during the Pacific War. Royama, founder of the study on International Politics in Japan, was one of the rare figures who continued to advocate the significance of regionalism. This chapter surveys Royama's argument on regionalism from the mid-1920's to the mid-1950's and investigates how his concern about development and nationalism of Asian countries appeared within the framework of regionalism. Royama's argument is also suggestive for better understanding of the context in which the "Rostow-Reischauer line" surfaced in the early 1960's.<br>Chapter III "Collective Security and Neutralism" elucidates several aspects of this issue which have not been hitherto fully investigated. Whether positively or negatively, neutralism in post-war Japan has been understood as a typically "idealistic" attitude toward international politics. However, the context in which the concept of neutrality was understood and argued in the early post-war Japan was more complicated. Discourses on neutralism at that time had still echoes of the controversies over collective security during the inter-war years. The Yokota-Taoka Controversy which took place in the late-1940's witnessed the continuity of pre-war and post-war arguments on this issue. This chapter, therefore, focuses on the Yokota-Taoka Controversy and analyses its impact on the following arguments of

- 著者

- 柳田 陽子

- 出版者

- JAPAN ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.35, pp.91-110, 1968