1 0 0 0 臺灣高砂族の語にて「臼」と「杵」といふ詞について(二)

1 0 0 0 ポロウィジョの位相

- 著者

- 中島 成久

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:00215023)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.47, no.4, pp.391-400, 1983

1 0 0 0 月と不死 : 沖繩研究の世界的連關性によせて

- 著者

- 石田 英一郎

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:00215023)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.15, no.1, pp.1-10, 1950

N. Nevskii recorded on the islands of Miyako, Okinawa, a folk-tale which explains the dark spots on the moon as the form of a man carrying two water-pails with a pole, as a punishment for his sin of pouring water of rejuvenescence on serpents, and water of death on men, the opposite of what the gods had ordered him to do. Although the present-day Japanese see in the moon-spots a hare pounding rice-cake, we find in the Manyoshu, compiled in the 7-8th centuries, the phrase "water or rejuvenescence in the hands of Tsukiyomi (moon, moon-man)". The above-mentioned Okinawan tale suggests that the Japanese also had at one time a belief that the moon-man carried the water of life. The author traces the distribution of the motif of the humam figure with a water-pail (or pails) in the moon from Northern Europe through Siberia (the Yakuts, the Buryats, the Tungus) and East Asia (the Goldi, the Gilyaks, the Ainu, the Okinawans) to N. W. North America (the Tlingit, the Haida, the Kwakiutl) and New Zealand. He traces the motif of a hare (or a rat) from South Africa through India, the South Seas, Tibet, China, Mongolia, Japan etc. to North America, and finds in some folk-beliefs with the latter motif the same idea of the origin of human death as in Okinawa. Both motifs must have originated in the primitive belief of seeing in the eternal repetition of waxing and waning of the moon its immortal life or rejuvenescence, and the water carried by the moon-man (or moon-woman) must originally have meant the water of life or rejuvenescence, as in the case of the Okinawan folk-tale.

1 0 0 0 OA 障害の文化分析 : 日本文化における『盲目のパラドクス』

- 著者

- 杉野 昭博

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.54, no.4, pp.439-463, 1990-03-30 (Released:2018-03-27)

本論の目的は「障害」についての文化分析の視点を検討することである。まず第一に, この視点の成立経緯をたどることによりその特徴を明らかにし, 次にこの視点から従来の日本の障害研究を批判的に検討することによってこの視点の意義が明らかにされる。さらに縁起や説話を題材としてそこに見出される盲目あるいは盲人の表象形態を日本における盲人文化としてとらえ, これに文化分析を適用する。つづけてこれらの盲人文化を担った日本の伝統的盲人職能集団の社会的性格に考察をすすめ, 「障害」を社会的=文化的コンテクストの中で全体的にとらえることにより「障害」を抱摂する社会の<民俗福祉文化>を明らかにする人類学的アプローチの可能性が検討される。結論としてゴフマンのスティグマ論について批判的検討が加えられる。

1 0 0 0 「老人と子供」について

- 著者

- 宮田 登

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:00215023)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.46, no.4, pp.426-429, 1982

1 0 0 0 OA 「肉の政治学」 : サダン・トラジャの死者祭宴

- 著者

- 山下 晋司

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.44, no.1, pp.1-33, 1979-06-30 (Released:2018-03-27)

The people of the Sa'dan Toraja, the southern branch of the mountain people ("Toraja") in Central Sulawesi of Indoncsia, often say, "We live to die." An anthropologist who studies their society would understand that these words carry crucial implications. The ritual of the dead is their central concern and every effort during life is directed toward death. They accumulate wealth to spend it almost all on the occasion of death. The people who live as members of Toraja society cannot abandon this custom, because the obligation to hold a ritual for the deceased and to participate in the rituals for the relatives or neighbours forms an essential part of their own identity. Even the villagers who have been converted to Christianity or received modern education cannot despise these conventions. If they neglect this "old-fashioned and "irrational" practice they will lose their position in the village community. Thus it may not be an exaggeration to say that their society revolves around "death". This paper aims first to describe the death ritual of the Sa'dan Toraja in detail and, second, to discuss several important problems it contains, based on the data collected during my field research from September 1976 unti January 1978. Although the economy is now founded upon wet rice cultivation in the beautifully terraced fields on the mountain slopes at 800 to 1, 600 meters above sea level, the culture of the Sa'dan Toraja shows striking features of the swidden cultivators in Southeast Asia, that is to say, feasts with the sacrifice of cocks, pigs and water buffaloes, the erection of megaliths, head hunting practices, the use of ship motifs and so on. In particular their death ritual has much in common with the "feast of merit" as it is found among the upland peoples of mainland Southeast Asia. This fact leads me to the assumption that the death ritual of the Sa'dan Toraja is a kind of transformation or developed form of "feast of merit" with pompous stage-setting and elaborate arrangement which is attained by the increase of wealth through the introduction of wet rice cultivation. Therefore, it seems to me more relevant to call their ritual of the dead "death feast", the "feast of merit' on the occasion of death. The death feast is strictly ranked, according to their custom. The rank and scale of the feast, measured by the amount of sacrificed water buffaloes and the main feast, which is counted by the day, depends upon the social rank and wealth of the deceased and his family. In the death feast named dirapa'i, the highest rank, scores of water buffaloes and more than one hundred pigs are consumed for the period of the feast that covers in total one or more years. In the "autocratic" southern villages of the regency of Toraja Land it is the threefold division of social classes the nobles or chief class (puang) , commoners (to makaka) and "slaves" (kaunan) that plays an important role in determining which rank of the feast to hold. Thus, the wealthy noble or the man of the chief class hopes, or is required, to hold a great feast of high rank, because the funeral ceremony gives him the opportunity to reaffirm his socio-political status or rather promote his prestige in his village community. In order to give the full picture of the death feast in the Sa'dan Toraja, the argument of this paper is presented through three main stages of discussion. The theme in each stage is as follows: (1) examination of the ritual categories of the Sa'dan Toraja, (2) a case study on a death feast, and (3) the presentation of some important problems which the death feast contains.

1 0 0 0 アイヌ研究の問題点と研究の緊急性(<特集>現代の「狩猟採集民」)

- 著者

- 小谷 凱宣

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:00215023)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.61, no.2, pp.245-262, 1996

- 被引用文献数

- 1

1996年4月の「ウタリ対策に関する有識者懇談会報告書」の提出により,アイヌ研究の推進は,より重要かつ緊急になってきた。有識者懇談会報告書の内容は,ウタリ協会の「アイヌ新法」制定要求に対する具体的措置の第一歩と考えられ,その意味でアラスカ先住民の先住権を全面的に承認したアメリカ連邦政府現地特別委員会報告に対比できる。そして,現地特別委員会報告にもとづいて制定された「アラスカ先住民諸要求解決法」(ANCSA)」は「アイヌ新法」内容のモデルになっていると解釈できる。本稿ではアラスカ先住民の先住権などに対する行政措置を決めた現地特別委員会報告(1968)とANCSA(1971)の内容を紹介する。それらに照らして,有識者懇談会報告書の内容を検討し,アイヌ新法制定要求内容の三本柱のうち,文化振興策のみが触れられただけで,先住権承認とアイヌ民族基金設置要求については触れられていないことを指摘する。ついで,有識者懇談会報告書で強調されているアイヌの総合研究の推進に焦点をおき,アイヌの博物館コレクションを中心に,いままでのアイヌ研究の問題点を指摘する。そのうえで,1980年代前半から実施してきたB・ピウスツキのアイヌ資料研究と在北米アイヌ関係資料の現地調査の結果にもとづき,アイヌの総合研究の必要性を具体的の考慮,提案する。未刊行資料の再発掘やその意義の再検討は,狩猟民文化が世界的に変容しつつある昨今,緊急を要する課題であると考えるからである。

1 0 0 0 OA 第 14 回 日本人類学会・日本民族学協会連合大会

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.23, no.4, pp.343-347, 1959-11-25 (Released:2018-03-27)

1 0 0 0 中国の民間宗教集団 : 構造的特性について

- 著者

- 佐々木 衞

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:00215023)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.53, no.3, pp.280-300, 1988

中国の民間宗教が多様な姿を持つことに, 研究者は多くの関心を払ってきた。本稿ではフリードマン等が提示した中国社会の統一性と多様性に関する命題から, その全体的な姿を理解する手掛を示した。中国の民間宗教には宗族の祖先祭祀や廟の祭祀の他に, 歴代の朝延から弾圧され続けた民間宗教集団のものがある。宗教集団を構成する絆は師弟が結ぶ個人的な関係より他はなく, 宗教集団は師弟の絆を越えた実在を持つことができなかった。この構造においては, 伝統的な宗教権威は継承され難く, 集団の統一は頭目のカリスマ的実力に頼らざるを得ない。中国の民間宗教集団の活動には, 「伝統型」「分派型」「自唱型」の3つの位相がある。教義・組織・活動の範例として大きな影響力を持ったのは, 「伝統型」の位相の集団である。しかしこの位相の集団も教首の法燈を守るのは容易でなく, 幾代もつづいて継承されたのはごく少数であった。その存在は神格化されて広く一般民衆の中に流布した。教派の具体的な姿は, 幾多の「分派型」がくり返し出現する中に新しく更新されていった。中国の民間宗教を全体的に理解するには, 宗族と村廟の祭祀に加えて, こうした宗教集団の活動をも重ね合わせて透視することが必要であろう。中国社会の構造原理を解明する上でも, 欠かすことのできない問題である。

- 著者

- 今村 豊 池田 次郎

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.14, no.4, pp.311-318, 1950 (Released:2018-03-27)

According to Dr. Kiyono, the modern Japanese are the result of physical change, having developed out of a prehistortc type, through a protohistoric intermediate type, with some Korean admixture. The Ainu, being different from the peoples either of prehistoric or protohistoric periods, had nothing to do with the formation of the modern Japanese. These conclusions are said to be derived, with statistical procedures, from a survey of skeletons of all those periods. Thus, if there were defects in his chronology of skeletons and his anthropometrical methods, his conclusions would be questionable. In the first place, because of insufficient description of the excavations and the relation to other relics excavated, the chronology of skeletons is ambiguous. Furthermore, several errors can be pointed out. In the second place, there are defects in his anthropometric methods. When measurements are compared, the characteristics compared are not always of the same kind, and therefore the basis of comparison fluctuates. The "mittlere Typendifferenz" is calculated only between the most convenient materials, and general conclusions are drawn in spite of the fact that the interrelations between all materials have not been exhaustively worked out. On the basis of Dr. Kiyono's own anthropometrical data, the reviewers have calculated the "Typendiffirenz" between all materials exhaustively, and reached the following results : 1) Though Dr. Kiyono concludes that the difference between the modern Japanese and their adjacent peoples is greater than that between local types of the modern Japanese, his evidence, especially with reference to the relation of the modern Japanese to the Koreans and Northern Chinese, cannot be validated. 2) On the basis of Dr. Kiyono's anthropometrical data, the Ainu, rather than the protohistoric Japanese, would more probably be regarded as the intermediate type between the modern Japanese and the prehistoric people. 3) Statistical evidence as to the mixture with the Koreans is lacking. In short, even provided that the chronology of materials were exact, it would be impossible to draw Dr. Kiyono's own conclusions from his own statistics.

本稿は, インド西ベンガル州のひとつの村落社会を事例に取り上げ, かつてこの地方で強力な覇権を揮っていたヒンドゥー王権と村落社会との関係を考察している。調査地は, インド亜大陸に分布する51の女神の聖地のひとつであり, その村落寺院は中世王権の寄進地を基盤にすることで, 複雑な祭祀体系が今日でも観察可能である。本稿は, 一年半の村落での住み込み調査の資料と, 英領期の土地資料とを統合することで, 村落社会の内部の視点から, 王権が村落の社会生活に深く関与している様子を描き出している。特に, 寺院の祭祀組織が, 王から村落のサーヴィス・カーストに賜与された寄進地と役割配分とに基礎付けられていることが示された。ここでは, 寺院の奉仕者は, 女神祭祀の役割を担うべく王によって任命されたサーヴァントなのであり, 宗教的でかつ政治的なこのような王の役割配分を通して, 王権の正統性が確立されることが論じられた。このような, 南アジア社会に固有の社会的歴史的条件に根ざした政治システムの考察は, 今日の世俗主義(secularism)と宗派主義(communalism)という図式的な対比にも再検討を迫るものとなるだろう。論文は, 8章で構成されている。序論では, 従来の王権論の議論を整理し, 村落社会との関係についての具体的な事例に基づく考察の必要性が論じられる。2章では, 調査村の概況が述べられる。3章では, 女神の聖地の特徴と王の寄進地が検討される。4章と5章は, 女神寺院での実際の儀礼過程が取り上げられる。6章では, 上記の資料に基づいて, 王権の正統性の確立過程が考察される。7章では, 特に, 調査村の独立後の変化に焦点が当てられる。最後に8章で, 結論が述べられている。

- 著者

- 大塚 和夫

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:00215023)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.50, no.3, pp.239-269, 1985

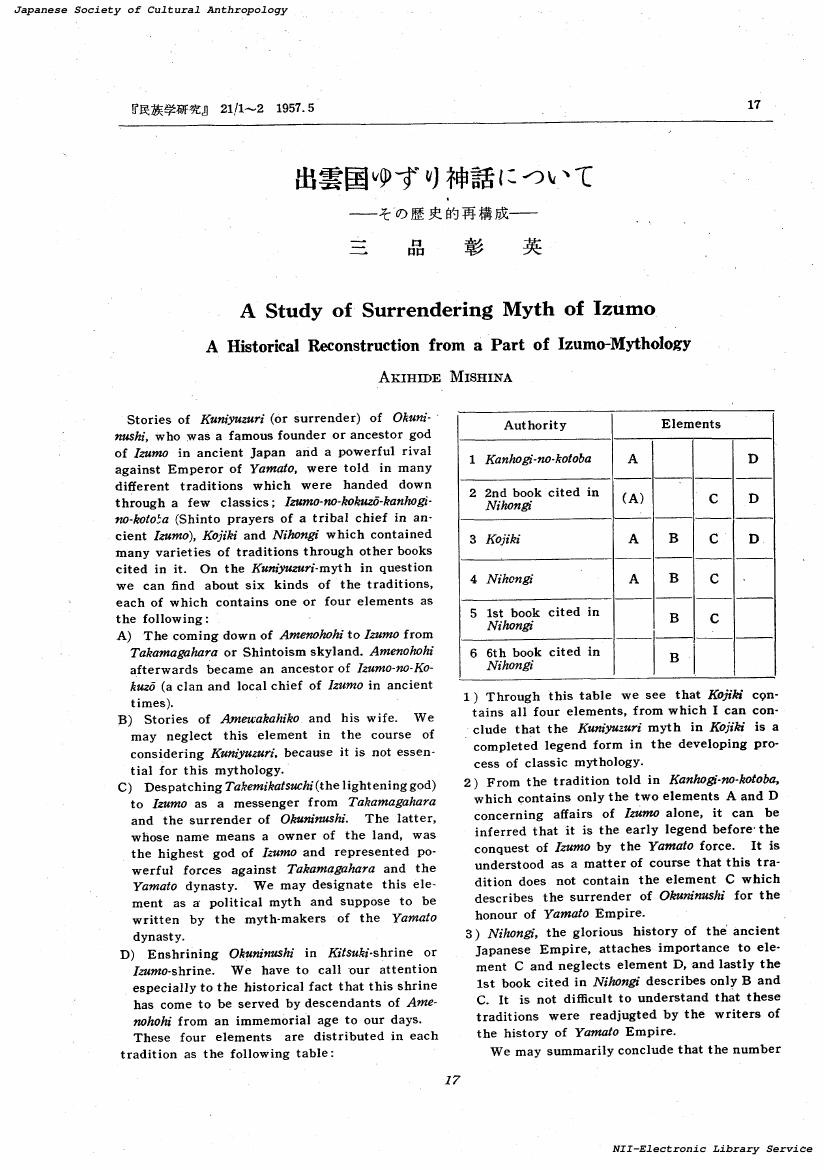

1 0 0 0 OA 出雲国ゆずり神話について : その歴史的再構成

- 著者

- 三品 彰英

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.21, no.1-2, pp.17-23, 1957-05-30 (Released:2018-03-27)

1 0 0 0 沖繩研究史 : 沖繩研究の人とその業績

- 著者

- 金城 朝永

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:00215023)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.15, no.2, pp.88-100, 1950

The name of Ryukyu (Luchu) first appeared in the Sui-shu (History of the Sui Dynasty). Some scholars considered that the Ryukyu mentioned here was another name for Okinawa, while others insisted that it was Formosa. Tan Shidehara, ex-President of Formosa University, criticized these ideas and concluded that it might be a colony of the old Ryukyuans in the southern part of Formosa, explored by the Chinese in early times. If his assumption is true, we may be able to reconstruct the culture and customs of old Okinawa through their colonial phase in Formosa. A no less interesting problem is raised by the legend of the Japanese hero and archer, Tametomo, who is said to have sired King Shunten, the first ruler (1187-1237 A.D.) of Okinawa according to the authorized history of Okinawa. This legend indicates the existence of a close connection between medieval Okinawa and Japan. The Yumiharizuki, a novel adapted from the legend, by Bakin Takizawa in the later years of the Tokugawa Shogunate, exerted a powerful influence upon the Japanese. There were not a few who having read the novel while young, made a visit to the legendary land. Another work on Okinawa of note during the Tokugawa period was the Nantoshi (Notes on Southern Islands), published in 1719, by Hakuseki Arai, a statesman and noted scholar of Chinese classics. After the Restoration of Meiji (1867), the Ryukyus were formally annexed to Japan in spite of Chinese protest, many Japanese came to Okinawa and wrote historical and geographical reports on the islands. As most of them were concerned with Japanizing the Okinawans, they stressed the concept of similar racial and cultural origins of the Okinawans and the Japanese, as well as the existence of close connections between them from early times. It was about half a century until the Okinawans themselves participated in research on their country. Among them, three of the most famous are Fuyu Ifa who devoted his life to the study of the Omorososhi (Collection of old songs of Okinawa), Anko Majikina, author of the History of Okinawa for IO centuries, and Kwanjun Higaonna, editor of the Nanto-Fudoki (Geographical Dictionary of Okinawa). Among the Japanese scholars who were interested in things Okinawan and not only supported but also instructed students in the field of Okinawan studies, are Kunio Yanagita, founder of Japanese Volkskunde, and Shinobu Orikuchi, noted poet and excellent folklorist. Both of thein visited Okinawa about 1920 for the research in folk religion and old customs, and made many contributions to the study of similarity between Japan and Okinawa. Yanagita organized the "Nanto-Danwa-kai." (Southern Islands Coversazione) and edited the "Rohen-sosho" (Fireside Series) in which are contained several works on Okinawa. With the moving of Ifa from Okinawa to Tokyo, the "Nanto-Danwa-kai" was reorganized by the Okinawans in Tokyo and named "Nanto-Bunka-kyokai" (Southern Islands Culture Association) which was the predecessor of the present "Okinawa-Bunka-Kyokai" (Okinawa Culture Association), now the only organ for studies on Okinawa in Japan. Before the war, in Okinawa, the "Okinawa-Kyodo-Kyokai" (Association for Studies on Okinawa) was established centering around Majikina, then President of the Okinawa Library, where there existed a collection of more than three thousand books on Okinawa. All of them were destroyed in air-raids. Since the end of the war, the Okinawans at home have been too preoccupied with their daily livelihoods and with the reconstruction of their war-devastated islands to resume studies on their own country. Members of the "Okinawa-Bunka-Kyokai", conscious of their mission to foster research on their culture, hold lecture meetings once a month and publish a bimonthly mimeographed organ.

- 著者

- 池田 不二男

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.31, no.4, pp.292-293, 1967-03-31 (Released:2018-03-27)

- 著者

- 松園 万亀雄

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.32, no.3, pp.243-245, 1967-12-31 (Released:2018-03-27)

1 0 0 0 OA 北海道アイヌの葬制 : 沙流アイヌを中心として

- 著者

- 久保寺 逸彦

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.20, no.1-2, pp.1-35, 1956-08-10 (Released:2018-03-27)

- 著者

- 中山 紀子

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:00215023)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.59, no.4, pp.453-463, 1995

- 被引用文献数

- 1

1 0 0 0 OA 日本における育児様式の研究 : 長野県村の育児様式に就いて(修士・博士論文要約)

- 著者

- 須江 ひろ子

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.24, no.3, pp.267-274, 1960-09-05 (Released:2018-03-27)

1 0 0 0 所有と分配の力学 : エチオピア西南部・農村社会の事例から

- 著者

- 松村 圭一郎

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:13490648)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.72, no.2, pp.141-164, 2007

本稿は、エチオピア西南部の多様な民族が居住する農村社会を対象に、土地から生み出される作物などの富がどのような手続きをへて、誰の手に渡っていくのか、富の所有と分配という問いを考察する。とくに「分け与えること」と「与えずに自分のものにすること」をめぐる人びとの相互行為から、所有や分配を支えている力学を浮き彫りにしたい。IIでは、農作物の分配行動に注目する。作物が収穫されたとき、雨季で食糧が不足するとき、持つ者は持たざる者から乞われたり、自発的に与えたりしている。じっさいに農民たちが誰にどのようなものを与えているか、具体的事例を分析することで、身近な親族から見知らぬ物乞いまで、さまざまな相手に対して富が分配されている実態を明らかにする。IIIでは、与える相手ごとの分配行動の差異に注目する。相手との社会関係が違うことで、分け与える背景にどのような違いがでるのか。「親族」と「よそ者」という対照的な相手に対する分配の事例から、それぞれに異なる動機が分配を促すきっかけとなっている可能性を示す。IVでは、人びとの分配をめぐる意識や葛藤について分析する。分配を定める宗教的な規律がある一方で、人びとは与えすぎると自分が困るというジレンマを抱えている。貧しい者が分配を受けるために行う働きかけのあり方と、与え手が分配を回避する事例から、与え手と受け手との相互行為において「分け与えること」と「与えずに自分のものにすること」が交渉されている点を指摘する。そして、Vで互酬性の議論を再検討しながら、「分け与える」という行為を支える相互的な「働きかけ」の重要性を提起する。