4 0 0 0 OA ライプニッツにおける「慈愛」(caritas)の概念

- 著者

- 酒井 潔

- 出版者

- 学習院大学

- 雑誌

- 人文 (ISSN:18817920)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.8, pp.7-20, 2009-03

ライプニッツのcaritas 概念は、一方で伝統的なキリスト教の立場に、他方で十七世紀の啓蒙主義の時代思潮にそれぞれ連続する面を有する。「正義とは賢者の慈愛である」(Justitia est caritassapientis)、そして「慈愛とは普遍的善意(benevolentia universalis)である」というライプニッツの定義には、キリスト教的な「善き意志」のモチーフとともに、(プラトニズム起源のものだけではない)近代の合理主義的性格が見出される。ライプニッツは彼の政治学、ないし政治哲学の中心にこのcaritas 概念をすえている。それは彼の「社会」(societas)概念とも密接にリンクしつつ、今日の社会福祉論への射程を示唆する。ライプニッツの「慈愛」、「幸福」、「福祉」(Wohlfahrt)という一連の概念のもつ広がりは、アカデミー版第四系列第一巻に収載されている、マインツ期の覚書や計画書に記載された具体的な福祉政策(貧困対策、孤児・浮浪者救済、授産施設、福利厚生など)に見ることができる。しかしcaritas 概念の内包を改めて検討するならば、caritas 概念の普遍性と必然性は、その最も根底においては、ライプニッツの「個体的実体(モナド)」の形而上学に基礎づけられている、ということが明らかになるであろう。In Leibniz' philosophy we find the very basic notion that philosophers, who recognize or are able to recognize that this world has been created by God, should try to bring about "the happiness of human beings, the benefit of society and the honor of God". This is precisely where the concept of "charity" as the "justice of the wise" is being conceived("Justitia est caritas sapientis"). Leibniz thinks that caritas can be equated neither with mere compassion nor with a particular religious virtue. For a rational human being, caritas belongs to the universal duties of practical life. Such a science - one that is called "politica" by Leibniz - is a discipline of practical philosophy. Leibniz' concept of caritas has two principal aspects: on one hand it has a traditional aspect deriving from Christian Antiquity and the Middle Ages; on the other hand it has a rational character derived from the idea that caritas must be based on reason and its proven knowledge. In this sense we can confirm that Leibniz belonged to that early idealistic period of the Enlightenment in the 17th century.

3 0 0 0 OA 三宅剛一差出・下村寅太郎宛書簡(下)

- 著者

- 酒井 潔 加瀬 宜子

- 出版者

- 学習院大学

- 雑誌

- 人文 (ISSN:18817920)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.7, pp.137-231, 2008

In the fi rst volume of Jinbun (2002) I published the fi rst 23 letters from Gouichi Miyake to Torataro Shimomura, with a further plan to publish the remaining 33 letters in the second volume. However, after that first publication, one of the pupils closest to Shimomura, Professor Atsushi Takeda, discovered many more letters as he continued his search. Therefore, I thought it better to wait until all of these letters were discovered. The letters from Miyake to Shimomura had reached 106 when Professor Takeda died from cancer unexpectedly in 2005. This meant the loss of the sole person in charge of Shimomura's study and opus postumum. So I have decided to publish these remaining 83 letters in this number of Jinbun (Nr.7), though we cannot exclude absolutely the possibility that further letters may be found. While most of the fi rst letters published were written before or during the war, most of this second batch of 83 letters were written after the war, and the last one can be dated approximately from the end of the 1950s to before 1964. We can see from the texts of these very valuable documents how the philosophers of the so-called "Kyoto School", the pupils of Kitaro Nishida (1870-1945), tried to promote their studies and to help each other during that diffi cult, catastrophic period; especially, how Miyake and Shimomura, pupils of Nishida, made great eff orts to reconstruct Japanese philosophical society and to lead incoming scholars to the principle of academic philosophy and of "systematic thinking". As for the development of the philosophy of Miyake, one can notice that he already mentioned in that period his turn toward an empiricist standpoint after engaging with the philosophy of mathematics, the phenomenology of Husserl and Heidegger, and the history of philosophy from Greek to Kant and German idealism. This fact demonstrates Miyake's "Humanontology" (Ningensonzairon) which is presented and thematised in his second main work Human Ontology (Tokyo, 1966), makes its appearance much earlier than one had once supposed. (Kiyoshi Sakai)

3 0 0 0 OA 西田幾多郎と三宅剛一

- 著者

- 酒井 潔

- 出版者

- 西田哲学会

- 雑誌

- 西田哲学会年報 (ISSN:21881995)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.5, pp.21-43, 2008 (Released:2020-03-24)

Goichi Miyake(1895‐1982)war zweifellos einer der bedeutendsten Schüler, die sich Kitaro Nishid(a 1870‐1945) durch seine Lehrtätigkeit in Kyoto erworben hat. Nachdem Miyake an der kaiserlichen Universität Kyoto sein Studium(1916‐19)abgeschlossen hatte, war er über zwanzig Jahre Assistenzprofessor für Wissenschaftslehre an der Kaiserlichen Universität Tohoku(Sendai). Nach dem zweiten Weltkrieg lehrte er in Sendai, Kyoto und Gakushuin(Tokyo)jeweils als Ordinarius für Philosophie. Im Vergleich zu anderen Philosophen, die zur “Kyoto Schule”gehörten, wie etwa Iwao Kouyama, Keiji Nishitani, ist Miyake nicht ganz so bekannt. Denn er schrieb fast keine Essais und er nahm nicht am Motiv des “absoluten Nichts”teil. Zudem lag sein Arbeitsplatz Sendai ungefähr 700 Kilometer von Kyoto, dem damaligen Philosophenzentrum entfernt. Aber Miyakes Hochachtung für Nishida hat sich durch sein Leben hindurch nie verändert. Auch Nishida fragte Miyake oft nach seiner Meinung oder seinem Urteil. Beide diskutierten über die philosophischen Kernfragen, die im Mittelpunkt von Nishidas System stehen. Vor allem sprachen sie über die “Geschichte”. Hier entwickelte sich ein ernsthafter und kritischer Dialog. Was ist die Geschichte? Nishida und Miyake stimmen zwar darin überein, dass die Geschichte nicht als eine bloss metaphysische Konstruktion zu behandeln ist, vielmehr soll sie im Selbstbewusstsein des Einzelnen aufgewiesen werden. Aber Nishida geht weiter als Miyake, so dass alles Wirkliche in “absolut widersprüchlicher Selbstidentität”zu finden ist, d.h. idealistisch in der “Geschichte”im Nishidaschen Sinne enthalten ist. Dagegen definiert Miyake die Geschichte als einen “kontextlosen Zusammnehang der sozial funktionierenden Wirkungen”, d.h. nach Miyake soll die Identifizierung der ganzen Wirklichkeit mit der Geschichte, als eine“unrichtige Verganzheitlichung der Geschichte”, wie dies bei Nishida, Hegel, Marx u.a.der Fall ist, kritisiert werden, An diesem Dialog ist für uns heute sehr lehrreich, ja sogar überaus beeindrückend zu sehen, wie und aus welchem Grund Miyake Nishidas “Geschichts”begriff als “absolute widersprechende Selbstidentität”zu kritisieren versucht, ohne dass Miyake seinen tiefen Respekt sowohl vor der Person wie auch vor der Philosophie seines Lehrers verliert.

2 0 0 0 IR 『華厳経』と『モナドロジー』 : 村上俊江におけるライプニッツ受容

- 著者

- 酒井 潔

- 出版者

- 学習院大学

- 雑誌

- 東洋文化研究 (ISSN:13449850)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.16, pp.326-356, 2014-03

Literature on Philosophy or the history of religion sometimes suggests that Leibniz's Monadology (1714) and Kegon-Gyô - also known as the Buddhist philosophical tradition introduced into Japan from China in the eighth century - present almost the same content in many respects. However, no text-orientated precise analysis of the theme was made until Toshie Murakami (1871-1957) wrote Raibunittsu-shi to Kegon-shû (Mr. Leibniz and Kegon\Buddhism) as his graduation thesis, originally presented to the Imperial University of Tokyo in 1896. The first and only contribution to the topic by Murakami, however, remained unknown until his paper was collected in Kegon Shiso (The Thought of Kegon), edited by Hajime Nakamura in 1960. At that point, for the first time, one realized the solid contribution Murakami had made not only to Leibniz Studies but also to Philosophy of East-West Dialog. Murakami concludes in his article that there is no difference between Leibniz's concept of "monad" and the Buddhistic idea of "Jijimuge"(事々無礙) or the doctrine of the Kegon school that every individual already comes out from itself and that, at the same time, it goes into each other without any barrier.

2 0 0 0 OA <論説>『華厳経』と『モナドロジー』 : 村上俊江におけるライプニッツ受容

- 著者

- 酒井 潔

- 雑誌

- 東洋文化研究 (ISSN:13449850)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.16, pp.356-326, 2014-03-01

Literature on Philosophy or the history of religion sometimes suggests that Leibniz's Monadology (1714) and Kegon-Gyô - also known as the Buddhist philosophical tradition introduced into Japan from China in the eighth century - present almost the same content in many respects. However, no text-orientated precise analysis of the theme was made until Toshie Murakami (1871-1957) wrote Raibunittsu-shi to Kegon-shû (Mr. Leibniz and Kegon\Buddhism) as his graduation thesis, originally presented to the Imperial University of Tokyo in 1896. The first and only contribution to the topic by Murakami, however, remained unknown until his paper was collected in Kegon Shiso (The Thought of Kegon), edited by Hajime Nakamura in 1960. At that point, for the first time, one realized the solid contribution Murakami had made not only to Leibniz Studies but also to Philosophy of East-West Dialog. Murakami concludes in his article that there is no difference between Leibniz's concept of "monad" and the Buddhistic idea of "Jijimuge"(事々無礙) or the doctrine of the Kegon school that every individual already comes out from itself and that, at the same time, it goes into each other without any barrier.

- 著者

- 酒井 潔

- 出版者

- 滋賀大学

- 雑誌

- 彦根論叢 (ISSN:03875989)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.287, pp.79-94, 1994-01-31

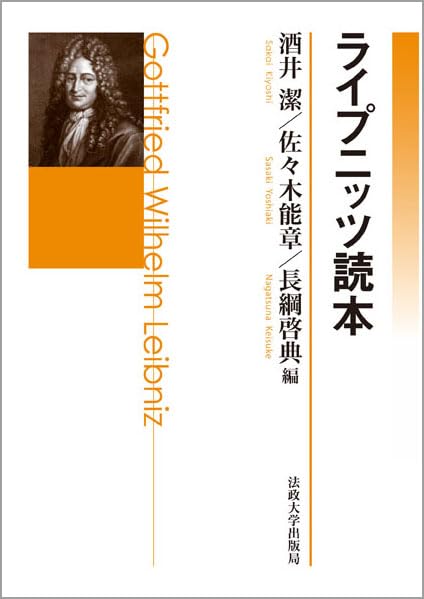

2 0 0 0 ライプニッツ読本

- 著者

- 酒井潔 佐々木能章 長綱啓典編

- 出版者

- 法政大学出版局

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 2012

- 著者

- 酒井 潔

- 出版者

- 日本ライプニッツ協会

- 雑誌

- ライプニッツ研究 (ISSN:21857288)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.7, pp.75-77, 2022-12-20 (Released:2023-11-14)

- 著者

- 酒井 潔

- 出版者

- 日本ライプニッツ協会

- 雑誌

- ライプニッツ研究 (ISSN:21857288)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.7, pp.1-25, 2022-12-20 (Released:2023-11-14)

1 0 0 0 OA ライプニッツにおける 「慈愛」 (caritas) の概念

- 著者

- 酒井 潔 Kiyoshi Sakai

- 出版者

- 学習院大学人文科学研究所

- 雑誌

- 人文 (ISSN:18817920)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.8, pp.7-20, 2010-03-28

"ライプニッツのcaritas 概念は、一方で伝統的なキリスト教の立場に、他方で十七世紀の啓蒙主義の時代思潮にそれぞれ連続する面を有する。「正義とは賢者の慈愛である」(Justitia est caritassapientis)、そして「慈愛とは普遍的善意(benevolentia universalis)である」というライプニッツの定義には、キリスト教的な「善き意志」のモチーフとともに、(プラトニズム起源のものだけではない)近代の合理主義的性格が見出される。ライプニッツは彼の政治学、ないし政治哲学の中心にこのcaritas 概念をすえている。それは彼の「社会」(societas)概念とも密接にリンクしつつ、今日の社会福祉論への射程を示唆する。ライプニッツの「慈愛」、「幸福」、「福祉」(Wohlfahrt)という一連の概念のもつ広がりは、アカデミー版第四系列第一巻に収載されている、マインツ期の覚書や計画書に記載された具体的な福祉政策(貧困対策、孤児・浮浪者救済、授産施設、福利厚生など)に見ることができる。しかしcaritas 概念の内包を改めて検討するならば、caritas 概念の普遍性と必然性は、その最も根底においては、ライプニッツの「個体的実体(モナド)」の形而上学に基礎づけられている、ということが明らかになるであろう。

1 0 0 0 OA シキミ有毒成分の分離,含有量並に毒性の検討

1 0 0 0 シキミ有毒成分の分離,含有量並に毒性の検討

1 0 0 0 ライプニッツの政治哲学--社会福祉論を手引きとして

- 著者

- 酒井 潔

- 出版者

- 理想社

- 雑誌

- 理想 (ISSN:03873250)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.680, pp.156-172, 2008

1 0 0 0 OA 初期ライプニッツの「正義」概念 ―「衡平」aequitasを中心に―

- 著者

- 酒井 潔

- 出版者

- 日本イギリス哲学会

- 雑誌

- イギリス哲学研究 (ISSN:03877450)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.40, pp.5-17, 2017-03-20 (Released:2018-07-25)

- 参考文献数

- 22

1 0 0 0 OA 2-エチル-1-ヘキサノールによる室内空気汚染 室内濃度,発生源,自覚症状について

- 著者

- 上島 通浩 柴田 英治 酒井 潔 大野 浩之 石原 伸哉 山田 哲也 竹内 康浩 那須 民江

- 出版者

- 日本公衆衛生学会

- 雑誌

- 日本公衆衛生雑誌 (ISSN:05461766)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.52, no.12, pp.1021-1031, 2005 (Released:2014-08-06)

- 参考文献数

- 36

目的 2-エチル-1-ヘキサノール(以下,2E1H)は,我が国で室内空気汚染物質として注目されることがほとんどなかった揮発性有機化学物質(以下,VOC)である。本研究では,2E1H による著しい室内空気汚染がみられた大学建物において,濃度の推移,発生源,学生の自覚症状を調査した。方法 1998年に竣工した A ビルの VOC 濃度を2001年 3 月から2002年 9 月にかけて測定した。対照建物として,築後30年以上経過したBビルの VOC 濃度を2002年 9 月に調査した。空気中カルボニル化合物13種類はパッシブサンプラー捕集・高速液体クロマトグラフ法で,その他の VOC41 種類は活性炭管捕集・ガスクロマトグラフ-質量分析(GC-MS)法で測定した。2002年 8 月に床からの VOC 放散量を二重管式チャンバー法で,空気中フタル酸エステル濃度をろ過捕集・GC-MS 法で測定した。講義室内での自覚症状は,2002年 7 月に A ビル315名および B ビル275名の学生を対象として無記名質問票を用いて調査した。結果 2E1H だけで総揮発性有機化学物質濃度の暫定目標値(400 μg/m3)を超える場合があった A ビルの 2E1H 濃度は冬季に低く,夏季に高い傾向があったが,経年的な低下傾向はみられなかった。フタル酸エステル濃度には 2E1H 濃度との関連はなかった。2E1H 濃度は部屋によって大きく異なり,床からの 2E1H 放散量の多少に対応していた。床からの放散量が多かった部屋では床材がコンクリート下地に接していたが,放散量が少なかった部屋では接していなかった。講義室内での自覚症状に関して,2E1H 濃度が低かった B ビル在室学生に対する A ビル在室学生のオッズ比の有意な上昇は認められなかったが,鼻・のど・下気道の症状を有する学生は A ビルのみにみられた。結論 2E1H 発生の機序として,床材の裏打ち材中などの 2-エチル-1-ヘキシル基を持つ化合物とコンクリートとの接触による加水分解反応が推定された。両ビル間で学生の自覚症状に有意差はなかったが,標本が小さく検出力が十分でなかった可能性もあった。2E1H 発生源対策とともに,高感受性者に注目した量反応関係の調査が必要である。

1 0 0 0 子宮摘出後婦人の性反応

- 著者

- 酒井 潔 山本 哲三 神谷 博文

- 出版者

- 日本産科婦人科学会

- 雑誌

- 日本産科婦人科学会雑誌 (ISSN:03009165)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.35, no.6, pp.p757-763, 1983-06

斗南病院で4年間に子宮全摘除術を受けた632例の患者に手紙を出し,アンケート調査に対する協力を依頼した.応募数は214例で回収率は38.4%であった.このうちから両側卵巣摘除群,無配偶者群,およびMPIテストにおけるL-スコア高値群を除く171例が調査の対象となった.手術後性反応の変化についてみると,性的欲求は減退67例(39.2%),不変89例(52.0%)また性交時分泌物では減退79例(46.2%)が不変68例(39.8%)を上まわった.年齢との関係でみると,高年で手術をうけるほど術後の減退は著明で30代では7例(24.1%)が術後性的欲求が減退したのに対して50代では13例(72.2%)に減退がおこった.術後,子宮喪失感を自覚する女性が77例(52.0%)ありこの群で術後性交時分泌物が減退したものは54例(70.1%)におよんだ.それに反して子宮喪失感を自覚しない群では性交時分泌物の減退を訴えるものは25例(35.2%)にとどまった.子宮摘出後,性交時に子宮からえられる感覚がなくなったと自覚する女性が39例(27.1%)あった.このなかで性感の獲得が困難となったと訴えたものは27例(69.2%)におよんだ.一方,性交時子宮感覚を自覚しない群では術後性感の獲得が困難となったものは19例(18.1%)にすぎなかった.一般に性交時子宮からえられる感覚を自覚しない群では子宮摘出後性反応の低下は軽微であるのに反して,性交時子宮感覚を自覚する群が子宮摘除術を受けた場合,術後性反応の低下が著明におこることがあきらかにされた.