- 著者

- 一ノ瀬 俊也

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.123, no.2, pp.281-289, 2014

- 著者

- 大久保 桂子

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.95, no.11, pp.1795-1796, 1986

2 0 0 0 OA 岸信介と護国同志会

- 著者

- 東中野 多聞

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.108, no.9, pp.1619-1638,1713-, 1999-09-20 (Released:2017-11-30)

In 1960, Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke revised the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty. He was a well known politician, having been Minister of Commerce and Industry in the Tojo wartime cabinet. When Tojo requested Kishi to resign in order to reshuffle the Cabinet, Kishi declined, causing Tojo to yield and dissolve his Cabinet on July 18,1944. After the war, Kishi explained that his anti-Tojo actions were aimed at avoiding accusation as a war criminal after the War. There are only a few studies about his wartime politics. Kishi said that he spent his days in idleness after the resignation of the Tojo Cabinet and every study so far acccepts this explanation. The author of the present article doubts this point. After resignation of the Tojo Cabinet, Kishi and 32 others organized a political club called the "Gokoku Doshikai" within the House of Representatives. It consisted of socialists, generals, admirals, and nationalists. They adopted a committee system, established an office, and held study group once a week. Kishi was the virtual leader of this club. They carried out a nationwide campaign called the "National Defence Movement". Kishi also established an ultranationalist association, the "Bocho Sonjo Doshikai", in his hometown of Yamaguchi city. Author also investigates this group, and concludes that both Kishi and the Bocho Sonjo Doshikai were opposed to the end of war. The Gokoku Doshikai was based on one concept of national defence, a "productive Army", (seisan-gun), which aimed at strengthen the economic control. By unifying the munitions industries, Japan could use the materials more efficiently, in preparation for the decisive battle of the Japanese mainland through self-sufficiency. The Gokoku Doshikai was opposed to the Japanese government, because then Prime Minister Suzuki was aiming at ending the war, they denounced the government's policy vehemently; and when Suzuki decided to surrender, the Gokoku Doshikai and the Japanese army resisted. The author concludes that while Kishi contributed to the anti-Tojo movement, he was opposed to surrender. We can see the root of the Kishi's postwar faction in the "Gokoku Doshikai". After the war, two of its members entered the Kishi Cabinet, and five socialist members became the leaders of the Socialist Party. Here we see another point of continuity and discontinuity between prewar and postwar politics.

2 0 0 0 OA 紀元前五世紀後半のアテナイにおける宗教と民衆 : アスクレピオス祭儀の導入を中心に

- 著者

- 齋藤 貴弘

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.106, no.12, pp.2101-2125, 1997-12-20 (Released:2017-11-30)

The cult of the healing god Asklepios was a very popular one in the Greco-Roman world. The so-called Telemachos monument (SEG. XXV. 226) tells a story about the introduction of this god in Athens in 420 B.C. We already have many studies about Asklepios, but very few of these studies present an appropriate view concerning the significance which the introduction of Asklepios had on politics and religious activities in Athens in the last half of the fifth century. In conclusion, the author argues that the introduction of Asklepios in Athens was a religious policy to reconstruct the Athenian religious piety which had been squashed by the great plague. The new festival for Asklepios involved the following major themes. The Epidauria, the new festival for Asklepios, was an attempt to link the god Asklepios with the Eleusinian goddesses. Such an association would strengthen the Eleusinian cults by providing the Greek people, especially the Delian League, a concept they could easily identify with. In turn, this plan was supposed to provide Athens with a revival from the plague, and to encourage her allies to dispatch offerings of "first fruits" to Eleusis. The introduction of the festival and the construction of a shrine were carried out in cooperation with the Epidaurian priests, Eleusinian priests and Telemachos, all according to a detailed plan. But conflict arose between the Kerykes and Telemachos. The problem involved the enlargement of the Asklepieion, the sanctuary of Asklepios in the city. Telemachos' motive for an enlargement of this site would have concerned the establishment of the healing cult. Finally, this incident clearly identifies the religious changes that were occurring at this time. Furthermore, the multiplicity of values held by the people of Athens during this period can also be identified.

2 0 0 0 OA 割符に関する考察 : 日本中世における為替手形の性格をめぐって

- 著者

- 桜井 英治

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.104, no.7, pp.1211-1246,1360, 1995-07-20 (Released:2017-11-30)

Bills of exchange in medieval Japan, which were called saifu, are understood to have been a means of remittance useable only once. However, in the late medieval age new types appeared which were able to pass from hand to hand as valuable means of exchange. They worked as a means of not only remittance, but also payment and exchange, that is to say, as money. This can be proven by the fact that their face value was fixed at 10 kanmon, that between a drawer and a remitter merchants often stood as intermediaries, and that people in those days did not discriminate between saifu and zeni (coins). According to the extant copies of saifu, all of them bore a fixed face value of 10 kanmon, and were payable to bearers on sight or several days thereafter. Being payable to bearers made them suitable for passing from hand to hand, and being payable on sight or several days thereafter made their long negotiation possible. When their fixed face value is included, all the conditions on which they could be negotiated were satisfied. There were two important premises which allowed negotiable saifu to come into existence. One was that they stood neutral in terms of economic relations: they did not involve interest charges or commissions. The other was that all proper nouns except the name of the drawer (and the payer), were omitted from the face of the bills, which made it as simple as possible. What kind of idea maintained the system of saifu is difficult to attribute to one thing: the strange system by which a piece of paper bearing a large value no less than 10 kanmon could be negotiated without state intervention, but basically it must be, the author believes, the common illusion of a "fetishism for documents" (which also had a large influence on the world of legal thought) that supported the credit of Saifu.

- 著者

- 佐藤 真紀

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.107, no.7, pp.1296-1319,1408-, 1998

2 0 0 0 フェリペ四世期ペルー副王領における献金

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.126, no.1, pp.1-35, 2017

フェリペ四世統治下のスペイン帝国は対外戦費の増大に伴う深刻な財政難に苦しんだ。王とその寵臣オリバーレス伯公爵は財政改革によって状況の打開を図ったものの、各地で暴動を招き、帝国の衰勢は決定的となる。このような状況下で、スペインの宮廷からは遠く離れ、かつ他の領土と同じく重い負担を求められながらも平穏を保ったのがペルー副王領である。この地でなぜ暴動が起きなかったのかを知るためには、導入された様々な財政策の実践過程と、植民地社会の反応を究明する必要がある。その財政策の中でも、歳入の増加に有効だったと評価されてきたのが、民から王に供された献金である。しかし、これまでの研究ではその額ばかりが注目され、実態が検討されてこなかった。そこで本稿では、ペルー副王領における献金について、その実現過程と植民地支配に及ぼした影響について考察を試みた。<br>本稿では、ペルー副王領において一貫して巨額の献金を集めていたクスコとポトシの二都市について事例分析を行った。そして、献金はその扱いが司教や行政官など在地の権力者の裁量に任されており、彼らの配慮がなければ実現不可能であったことを論じた。金銭負担に対する民の不満を和らげたのは権力者が彼らとの間に培った紐帯である。この権力者たちは多くの場合、王の任命を受けて新たに地域社会の外部からやってきた人々だったが、民に協力を求める過程で地域に根を張ってゆく。しかしこの繋がりは多額の献金を実現させて帝国の財政に利する一方、癒着に転じ巨大な損失を引き起こすこともあった。植民地社会の諸権力が地方で領袖化することの危険性を王室は認識していたが、それを促進する側面を献金という制度は持っていたと言える。かくして、スペイン王室にとって献金は諸刃の剣のようなものであったことが明らかになるだろう。

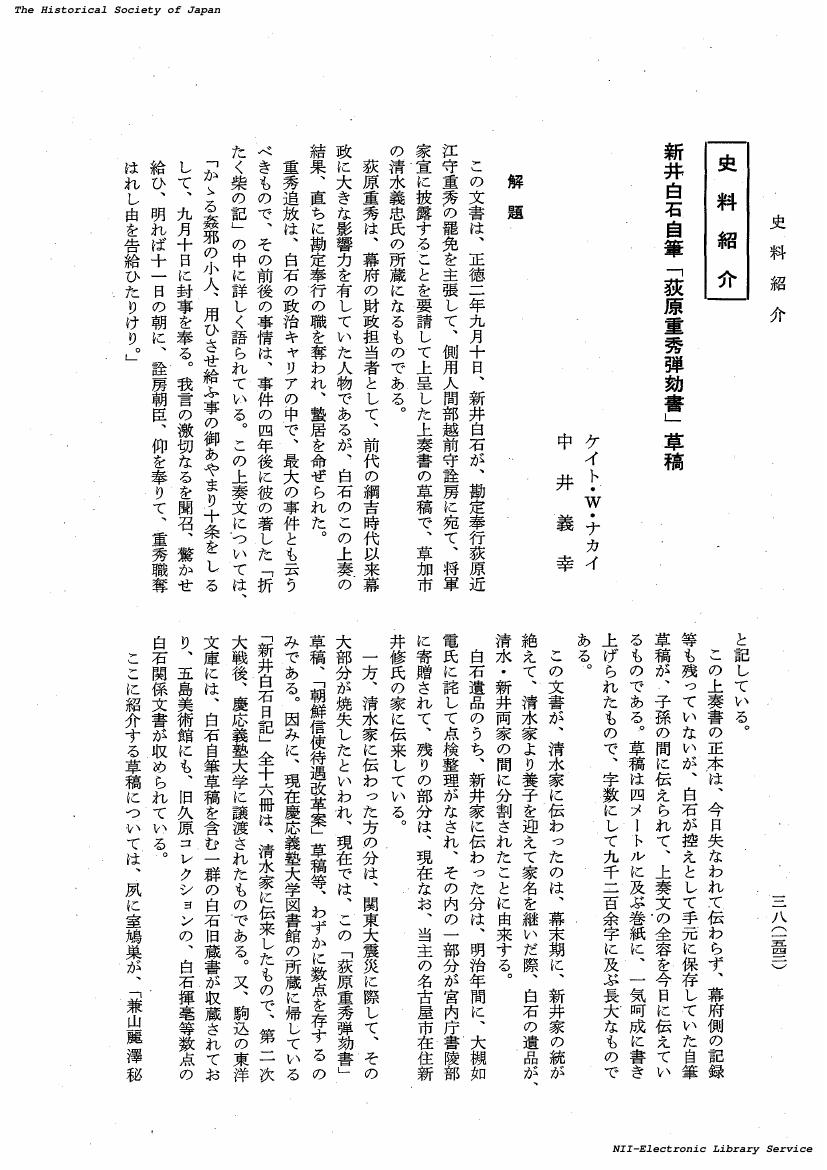

2 0 0 0 OA 新井白石自筆「荻原重秀弾劾書」草稿

- 著者

- ナカイ ケイト W. 中井 義幸

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.89, no.10, pp.1542-1553, 1980-10-20 (Released:2017-10-05)

2 0 0 0 日本 : 中世 六 (一九九一年の歴史学界 : 回顧と展望)

- 著者

- 久保 健一郎

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.101, no.5, pp.747-751, 1992

2 0 0 0 OA 日本 : 中世 五(一九八九年の歴史学界 : 回顧と展望)

- 著者

- 山室 恭子

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.99, no.5, pp.702-708, 1990-05-20 (Released:2017-11-29)

2 0 0 0 一 総論(近世,日本,二〇〇八年の歴史学界-回顧と展望-)

- 著者

- 大藤 修

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.118, no.5, pp.795-797, 2009

2 0 0 0 OA 摂関期における左右近衛府の内裏夜行と宿直

- 著者

- 鈴木 裕之

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.125, no.6, pp.37-62, 2016 (Released:2018-10-05)

本稿の目的は、内裏の夜間警備(夜行・宿直)の分析から、摂関期における左右近衛府の機能を検討することである。律令制以来、衛府は内裏警備を主たる職掌とした。夜間の警備も同じく規定されていた。延喜式段階でも、その職掌は継承された。本稿の問題意識は、このような内裏の夜間警備が摂関期(一一世紀)に機能していたか、あるいは貴族に認識されていたかという点にある。従来の研究で否定的に理解されてきた摂関期の左右近衛府の治安維持機能について、内裏夜行・宿直の観点から再検討した。 まず、延喜式の夜行・宿衛規定の分析を起点とした。夜行に関する諸規定から、六衛府すべてが内裏・大内裏の夜行に関与していることを指摘した。内裏夜行の検討が、摂関期の左右近衛府の性格を知るうえで有効であると判断した。また、宿衛は考第・昇進の条件として考えられていた。内裏夜行・宿衛の実態史料の分析から、その日常性が確認できた。 次に、一一世紀の左右近衛府の内裏夜行・宿直を考えるため、行事書・儀式書から次第を確認し、古記録から実態を検討した。その結果、摂関期における左右近衛府の内裏夜行・宿直の日常性が明らかとなり、貴族が治安維持組織たる左右近衛府を認識していたことを指摘した。 最後に、内裏夜行・宿直の有効性を補足する論点として、内裏火災における左右近衛府の活動に着目した。摂関期の内裏火災において、消火活動と予防組織としての左右近衛府の姿がみられた。消火・予防という活動の背景には、内裏夜行・宿直の有効性とそれに付随する貴族認識があると考えた。 従来の研究で否定的に理解されてきた左右近衛府の治安維持機能を、内裏の夜間警備を通じてみることで、肯定的に捉えようとしたのが本稿である。儀式関与・芸能・摂関家への奉仕など、様々な存在形態が認められる左右近衛府であるが、本来的な治安維持組織としての姿もその一つとして認めるべきであると結論づけた。

2 0 0 0 若松隆著『内戦への道 : スペイン第二共和国政治史研究』

- 著者

- 深澤 安博

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.96, no.7, pp.1186-1191, 1987

2 0 0 0 OA 歴史理論(2006年の歴史学界-回顧と展望-)

- 著者

- 佐藤 正幸

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.116, no.5, pp.614-618, 2007-05-20 (Released:2017-12-01)

2 0 0 0 官僚任用制度展開期における文部省

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.126, no.1, pp.39-66, 2017

本稿の目的は、1887年に制定された近代日本最初の官僚任用制度である試補及見習規則期における文部省の官僚任用と文部官僚に要求された専門性・専門知識について明らかにすることである。従来、文部省・文部官僚への言及は、主に教育史領域からなされてきたが、そこでは政策過程を解明することが主眼であり、文部省・文部官僚自体がいかなる組織・集団で、官僚制度の進展とどのように関連したのかといった視角は希薄であった。本稿では、多数の帝国大学法科出身者が各省へ入省する契機となった試補規則期に焦点を当て、文部省による官僚任用の実態を明らかにした。そのうえで、雑誌『教育時論』を用いることで、文部官僚が同時代的に要求された教育行政の専門性・専門知識に関する議論を浮き彫りにした。<br> 本稿の成果は以下の三点である。<br>(1)試補規則期の文部省の試補の採用は、多数を占める帝国大学法科出身者の任用は各省中最少であり、対照的に文科出身の試補全員を任用するという点で、各省の中でも独自の人事任用を行っていた。そして、省内多数を占めた省直轄学校長兼任者・経験者とともに、文科出身者は教育行政を担うに足る専門性・専門知識を持っていると考えられていた。<br>(2)文科出身者とは異なり、井上毅文相期の省幹部が「法律的頭脳」と批判されたように、法科出身者は教育行政官としての資質において批判を受ける可能性を持った。根底には、教育とは「一科の専門」であり、法学領域の能力とは別のものであるという見解があった。<br>(3)「法律的頭脳」と批判された木場貞長は、「行政」を主として教育行政を考える自身を「異分子」と認識した。そして、木場は文部省直轄の学校長などから学校の実情を理解しないと批判されに至った。木場のような思考を持つ文部官僚が主流となるのは、文官高等試験を経て、内務省の官僚が文部省へ異動し、局長などの省内幹部を占める明治末期まで待たなければならなかった。

2 0 0 0 OA 弁官の変質と律令太政官制

- 著者

- 大隅 清陽

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.100, no.11, pp.1831-1832,2004-, 1991-11-20 (Released:2017-11-29)

Under the Ritsuryo 律令 regime of Japan, the Benkan 弁官 formed a part of the Daijokan 太政官 system. It was an independent department of the Daijokan, and had original offices named the Benkan-cho 弁官庁 and the Benkan-soshi 弁官曹司. The Daijokan in a narrow sense was composed of only the Kugyo 公卿, the Shonagon 少納言 and the Geki 外記 and did not include the Benkan. The function of the Benkan was controlling central and local government offices organized under the Daijokan system, such as Hassho 八省 and Kokushi 国司. These offices informed the Benkan of state affairs by making oral reports as well as documentary ones. The Benkan also orally inquired of the officials about state affairs, and gave them proper instructions. In this way, the Benkan could completely control any government office. But this means that the Daijokan system of Japan was an undeveloped bureaucracy in contrast with the government system of the Tang dynasty In the Tang, every government office divided its affairs between the officials, the chief chang-guan 長官, the vice chief tong-pan-guan 通判官 and the pan-guan 判官. The directions of these officials were recorded in the documents, and the inspector jian-gou-guan 検勾官 of every office supervised their management and took delivery of documents sent by other offices. In Japan, however, there was no such system; only the Benkan controlled and supervised the management of every office as thoroughly as possible. This is the reason why the Benkan was a department separated from the Daijokan in a narrow sense, a cabinet formulating policies. In the ninth century, as the government offices established by the Ritsuryo code declined in their function and new administrative organs came into existence in the Imperial Palace Dairi 内裏, the Benkan also changed in substance. In the begining of the ninth century, the Daijokan in a narrow sense began to perform its duty in the Dairi, not in its original offices, but the Benkan continued to use its own offices. During this century, the Ritsuryo government offices further declined, so the Benkan lost its ability to control them. In the end of the century, the Benkan only sorted out the documents presented by many offices in the Katanashi-dokoro 結政所, the new office of the Benkan located on the east side of the Dairi. At the almost same time, the new administrative organs Tokoro 所 were established in the Dairi, and some Ritsuryo government offices; which had close relations with the Dairi, were reorganized under the Dairi's direct control. Later, the Benkan was appointed chief of the Tokoro and the government offices with the Kugyo and Tenjobito 殿上人, and was called Betto 別当. The establishment of the Katanashi-dokoro means that the Benkan also began to perform its duty in the Dairi. Moreover, the Benkan formed the original format of command, Benkan-ni-kudasu-senji 下弁官宣旨, imitating the Geki-ni-kudasu-senji 下外記宣旨, the way by which the Daijokan in a narrow sense had given the offices commands in the Dairi since the begining of the ninth century. In this way the Benkan's independence from the Daijokan in a narrow sense was diminished. On the contrary, the Benkan became the secretary directly responsible to the Daijokan, carrying out various affairs under the command of the Shokei 上卿, the person in charge of daily affairs in the Daijokan. This is the original form of the Benkan during the Sekkan 摂関 period, that was born at the end of the ninth century. The history of the Benkan under the Ritsuryo regime shows us how the Daijokan system changed and was reorganized.

- 著者

- 鈴木 董

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.123, no.1, pp.35-37, 2014-01-20 (Released:2017-07-31)

2 0 0 0 OA 二〇世紀インドのアーンドラ地方における言語州要求運動

- 著者

- 山田 桂子

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.98, no.12, pp.1938-1960,2049-, 1989-12-20 (Released:2017-11-29)

The federal system of India today is composed of linguistic states, corresponding to a linguistic division of the population, which emerged through general states reorganization in 1956. The idea of state reorganization on a linguistic basis in the preindependence era had been embodied from the 1920's through the "divide and ruie" policy adopted by the British government, and was taken up by the Indian National Congress out of the practical necessity to activate a national movement and to placate the muslim population. After independence, the INC shelved the issue on the grounds that linguistic states would pose a menace to national integration. The reorganization of the linguistic states in 1956, however, materialized because of the emergence of the state of Andhra in 1953, which had come into existence only after the fast and ensuing death of an agitator, and out of economic convenience to accomplish the 5 years' plan effectively. Andhra state, which led the states reorganization on a linguistic basis, was the consequence of the Andhra movement, which had been rising since the beginning of the 20th century in Andhra region, a part of the Madras Precidency, where Telugh language was spoken. The Telugu area was divided into Madras Precidency and Hyderabad Princery state. The Telugus were in the minority compared with the Tamils in Madras Precidency, and remained underdeveloped under the Muslim rulers in Hyderabad. In 1953 the Andhra region seceded from Madras state and named their territory Andhra state. Then Andhra Pradesh was formed in 1956, a united Telugu state annexing the Telugu area in Telangana. However, there emerged a strong demand for a separate Telangana state in 1968 led by people discontented with the economic imbalance. Why did such separatism have to take place in Andhra Pradesh, which was considered as the pioneer and model linguistic state in free India? The consistent phenomenon through Andhra Movement was the ascent of the castes on the political scene. The Andhra Movement was started by Telugu Brahman, and the largest landed non-Brahman caste groups, the Reddy and Kamma, participated in the movement during late 20's and 30's. In particular, the Reddy, widely spread throughout the Telugu area, came to power, which enable surpass the Brahmans, because they were reorganized and united by the emergence of a united Telugu state. Moreover, after Andhra Pradesh was formed, the people who belonged to the minor castes and factions gained influence in state politics and led a movement to agitate for a separate Telangana state. In short, the Andhra Movement was represented the ascent of the Reddy carried out around the symbol of Telugu language ; and the Telangana Separatists Movement was represented the ascent of the minor castes caused by economic imbalance. Thus, the inconsistent tendency to form and disunite the linguistic state can be seen in the consistent one of the steady ascent of castes.

- 著者

- 田崎 哲郎

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.92, no.12, pp.1952-1953, 1983

2 0 0 0 室町期鶴岡八幡宮寺における別当と供僧

- 著者

- 小池 勝也

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.124, no.10, pp.1699-1735, 2015

The aim of the present article is to examine the historical development of the Tsuruoka Hachiman Shrine (present day Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture) during the Muromachi period, a subject that has not been given serious attention from the time of the compilation of the History of Metropolitan Kamakura: Temples and Shrines in 1967. This article focuses on the Buddhist abbots (betto 別当) and monks (guso 供僧) who served the Shrine during its period of Shinto-Buddhist syncretism, while keeping in mind the presence of Muromachi Bakufu appointed governors (kubo 公方) of Kamakura. The line of betto who managed the Shrine's Buddhist affairs during the period have been described in the sources as strictly disciplining the Shrine's monks, replacing those they accused of misconduct, in the process of continuously and freely exercising their powers of appointment and thus expanding their sphere of personal influence over the monks under their jurisdiction. On the other hand, we also see a rise in incidences of monks resisting the authority of their betto, to an extent that during the last years of the Muromachi Bakufu, betto were altogether prevented from replacing their subordinates. Concerning the case of Koken, who served as the Shrine's 20th betto between 1355 and 1410, issuing directives to his subordinate monks using the seal of the Kamakura Kubo in Oei 7 (1400), the research to date has interpreted this act as a surrender of betto authority to the governor ; however, a rereading of the related primary sources reveals that such a general conclusion can not be reached from one isolated incident. Although there is no record of Koken's successor Sonken replacing any of his monks, there is the incident in Oei 22 (1415) in which the prestigious mountain ascetic title of "In" was bestowed on the Shrine's monks, but excluded any one not belonging to the Shingon (Toji Temple) Faction of esoteric Buddhism, indicating a discriminatory attitude towards those monks not under the betto's personal influence. Then a struggle arose over the appointment of Sonken's successor, which reverberated into secular politics, leaving Son'un as betto by virtue of the mass replacement of the Shrine's monks. Son'un's term of office was marked by further worsening of relations between the Shrine's betto and his monks, which developed into a situation of such turbulence that the Kamakura Kubo showed signs of possible intervention in the Shrine's personnel affairs, and ended up replacing Son'un. Incidentally, Sonchu, the Kubo's replacement, was executed for collusion with Ashikaga Mochiuji in the Shogun's younger brother's "rebellion" of 1438-39. The process by which the Buddhist sector of Tsuruoka Hachiman Shrine was transformed from an non-sectarian center of learning to a predominately Shingon Faction dominated institution, beginning in the mid-14th century, was by no means a peaceful one, as indicated by the rise of serious tension during that time between the Shrine's betto and the monks under their jurisdiction.