3 0 0 0 OA <書評論文>アメリカ「帝国」,「ならず者」国家,イスラム主義

- 著者

- 白石 隆

- 出版者

- 京都大学

- 雑誌

- 東南アジア研究 (ISSN:05638682)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.41, no.2, pp.262-266, 2003-09

この論文は国立情報学研究所の学術雑誌公開支援事業により電子化されました。

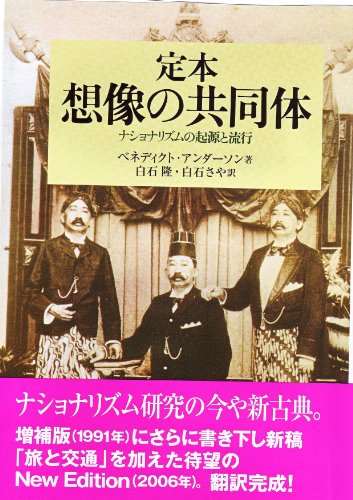

2 0 0 0 定本想像の共同体 : ナショナリズムの起源と流行

- 著者

- ベネディクト・アンダーソン著 白石隆 白石さや訳

- 出版者

- 図書新聞 (発売)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 2007

2 0 0 0 OA 新興国の政治と経済発展の相互パターンの解明

- 著者

- 園部 哲史 戸堂 康之 白石 隆 大塚 啓二郎 佐藤 寛 杉原 薫 恒川 惠市 鬼丸 武士 松本 朋哉 高木 佑輔 本名 純

- 出版者

- 政策研究大学院大学

- 雑誌

- 新学術領域研究(研究領域提案型)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 2013-06-28

研究期間全体を通じて、経済学者、政治学者と歴史学者が協力しながら、現在の新興国の政治と経済についての実証分析を行った。総括班は、各計画研究班の共同研究を行う場を提供し、分野融合マインドを持った若手研究者の育成にも力を入れた。その結果、新興国に独自の発展経路の在り方や、それに基づく新興国の課題の存在が解明された。領域全体の活動成果として、世界的な学術書の出版社であるSpringer Nature社のシリーズEmerging-Economy State and International Policy Studiesを新たに作り出し、本領域の成果を4巻からなる英文書籍として出版することになった。

1 0 0 0 OA 歌詞における言語情報を利用した作曲システム

1 0 0 0 OA 永積 昭著『インドネシア民族意識の形成』

- 著者

- 白石 隆

- 出版者

- 公益財団法人 史学会

- 雑誌

- 史学雑誌 (ISSN:00182478)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.91, no.2, pp.229-237, 1982-02-20 (Released:2017-11-29)

1 0 0 0 OA 上からの国家建設-タイ、インドネシア、フィリピン

- 著者

- 白石 隆

- 出版者

- JAPAN ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- 雑誌

- 国際政治 (ISSN:04542215)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1987, no.84, pp.27-43,L7, 1987-02-20 (Released:2010-09-01)

- 参考文献数

- 16

In the age of the United Nations, the state derives the meaning of its existence from the imagined nation, from the fiction that the executives of the modern state are a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole nation. From this, constitutional democratic thinking draws one conclusion: the key to legitimacy is the mandate of the nation/people, represented through fair and free elections; governmental performance in managing the common affairs of the nation is important, but it is translated into legitimavy only through elections. “Authoritarianism and development” thinking draws another: the legitimacy of a regime and hence regime stability ultimately depend on governmental performance in carrying out the common affairs of the nation, that is, national independence, unity, order and welfare. It is not the mandate of the nation/people represented through elections, but governmental performance itself that is the key to legitimacy. The ruling elite are those who know what the national goals are. The Important thing is to do the job. Legitimacy will come if the job is done well.Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines adopted this “authoritarianism and development” strategy for nation-building in the 1960s and 1970s with different results. Thailand and Indonesia have been successful in the task of state-building and are now trying to cope with the task of expanding political participation in different ways. In Thailand the bureaucratic polity has become a thing of the past and the search for a new form of “power-sharing” is now under way. In Indonesia, in contrast, the bureaucratic polity has been consolidated and the integratin of social forces in the regime is being attempted through functional representation. Only in the Philippines Marcos' “revolution from the center” and “democratic revolution” proved to be a dismal failure. But the argument Marcos made proved to be valid. It was indeed a “reoriented political authority” that initiated the “democratic revolution.”

1 0 0 0 OA 103. 肩挙上におよぼす上腕骨外旋の影響について

- 著者

- 沢田 豊秋 立花 孝 稲垣 かず子 河野 礼治 白石 隆司 稲垣 稔

- 出版者

- 公益社団法人 日本理学療法士協会

- 雑誌

- 理学療法学Supplement Vol.11 Suppl. (第19回日本理学療法士学会誌 第11巻学会特別号)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- pp.103, 1984-04-01 (Released:2017-06-29)

1 0 0 0 土屋健治会員のご逝去を悼む

- 著者

- 白石 隆

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 アジア政経学会

- 雑誌

- アジア研究 (ISSN:00449237)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.41, no.4, pp.119-120, 1995

1 0 0 0 OA 水圧緩衝式鋼製防玄材 : 高性能岸壁用

- 著者

- 白石 隆義

- 出版者

- 公益社団法人日本船舶海洋工学会

- 雑誌

- 日本造船学会論文集 (ISSN:05148499)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.125, pp.437-445, 1969-06

Japanese National Reilways has developed a new type berth fender for railway ferry berth, The fender is mainly composed of a box shaped steel slab whose front surface is smooth, and several water pressure shock absorbers which are made or rubber bags and attached to the back surface of the slab. The shock absorbing and damping properties of the absorber were proved excellent by half scale model tests. The results of the tests were compared with the results of approximate calculation.A trially constructed fender of this type (size=8 m×4 m) was fitted on a railway ferry berth in Uno port. Full size shock tests were carried out on this fender, and the results indicated the allowable breth touching speed might be doubled.

1 0 0 0 OA 土屋健治『インドネシア民族主義研究―タマン・シスワの成立と展開』

- 著者

- 白石 隆

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 アジア政経学会

- 雑誌

- アジア研究 (ISSN:00449237)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.31, no.1, pp.95-108, 1984 (Released:2014-09-15)

1 0 0 0 OA オーラルヒストリーの手法によるフィリピン開発主義体制の研究

2007年4月から2010年3月の3年間に及ぶ海外学術調査であり、フィリピンにおいてマルコス政権の独裁体制に参加したテクノクラートへの聴き取り調査と、当時の資料を発掘・データベース化を行った。インタビューは、合計16名を対象に、延べ36回にわたって実施された。インタビューは映像・音声・文書の形で、デジタル化された発掘資料(シックスト・ロハス文書、アーマンド・ファベリア文書)とともにフィリピン大学付属図書館で保管され、しかるべき時期に一般に公開される。

1 0 0 0 民主化・分権化後のインドネシアにおける地方政治経済構造の変容

インドネシアでは1998年のスハルト体制崩壊以降、民主化と分権化の進展によって、政治経済構造が大きく変容している。本研究はこうした地殻変動の実態を、特に地方政治に焦点を合わせて分析することを目的とした。地方政治を理解するにあたり、各研究者が各地の地方政治の特徴を分析するのみならず、インドネシア科学院(LIPI)政治学研究所との協力のもと、地方議会議員の社会学的プロフィールの収集にも努めた。2008年3月末までに、1州95県・市の地方議会議員合計3455人のデータ収集に成功した。2007年末時点でインドネシアには33州464県・市の自治体があることから、県・市については総議員数のうち約20.5%のデータを集めることができた。加えて、2004年から、地方議会議員が首長を選出する制度から直接公選制になり、候補者たちの社会学的プロフィールにも変化が見られている可能性があるとの判断から、地方首長選に出馬した正副首長候補者たちのプロフィール収集も行った。2008年初頭までに行われた297の首長選のうち、64の首長選に出馬した正副首長候補者のデータ収集に成功した。一つ明らかに言えることは、民主化後、都市部の若手中間層を基盤として台頭してきたイスラーム政党・福祉正義党が躍進していることである。ジャカルタ地方議会で第1党に躍り出たことに象徴されるように、イスラーム的倫理に基づく清廉潔白さを売りにして地方議会において着実に勢力を拡張し始めただけでなく、地方首長選では他政党同様に、選挙で勝てる俳優・女優などを擁立して「普通の政党」の様相をも見せ始めつつ、高い割合で正副首長の推薦候補を当選させることに成功している。