1 0 0 0 OA 第一次大戦後の北炭の労働運動対策

- 著者

- 市原 博

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.19, no.2, pp.38-64,iii, 1984-07-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

The subject of this paper is what kind of policy the management took to counter the labour union movement at the Hokkaido Coal and Shipping Company, called Hokutan, after the First World War, and how industrial relations at Hokutan was reformed.Hokutan became a affiliated enterprise of Mitsui Zaibatsu in 1913, and then the paternalistic policies were enforced there. The labour union was organized at Hokutan in 1919, the peak of the post-war boom. It was based on the consciousness as producer of mine workers. To control the mine workers against the labour union, the management organized the organization of employees, Issinkai, which fulfilled the function of the roundtable conference of labour and management and mutual aid association according to the idea of corporation of labour and management.The management carried out the wage cuts because of the damage due to the post-war crise in 1921. So the labour union went on strike in opposition to the wage cuts. At last the issue of this dispute was whether the management approved the labour union as a bargaining body or not. After this strike, the labour union was ruined, and the authority of negotiation about labour conditions was given to Issinkai. And the management succeed to make use of Issinkai to control the mine workers according to the idea of corporation of labour and management.

1 0 0 0 OA シュネーデル社の成長行動と経営組織 (一九一三年)

- 著者

- 藤村 大時郎

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.19, no.2, pp.1-37,i, 1984-07-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

Schneider and Company, a leading industrial enterprise in France, instituted the Rules to establish principles of its internal organization in 1913. Based on these Rules, I attempt to suggest an explanation for its administrative structure on the eve of the World War I, focusing on its operating units.Schneider, like other French industrial enterprises in those days, made little use of mass-production techniques, providing nonstand-ardized goods for producers and governments. However, Schneider had a high reputation as a maker of large, precision products which required a highest level of technology at that time to be fabricated, such as locomotives, marine engines, artillery, armorplates, bridges. As most of its products were made by order and small-batch, Schneider had grown, since its establishment in 1836, by continuously diversifying its products, and by diversifying in a number of industries. According to the Rules, Schneider made industry the basis of the organization of its production units : iron mines, coal mines, pig iron and steel producing, rolling mill, machine construction, electric machine construction, field artillery, naval artillery, forging and armorplate finishing, shipbuilding, mine making, bridge and building. Each of these units had its manager as well as its accountant's and engineer's offices, and formed a separate unit of accounts. Therefore each formed the “operating unit”, to use the term of professor Chandler, Jr., though many of them were in the same site, Le Creusot. Organizational imperatives at Schneider, however, showed clear differences to those at the American “modern business enterprise”.As most of its products required several months or more to be accomplished, and were made by order and small batch, Schneider organized its operating units to administer individual orders from the acceptance to the deliery. Thus the unit's accounts were organized to perform estimating and recording costs of separate orders. The controller's office was also formed to apparaise the unit's performance by order. Since each of these orders formed an autonomous administrative unit, the operating units which administered them remained autonomous. Though large enterprise with more than 10, 000 employees, Schneider was composed of numerous administrative units of orders, and of autonomous operating units.Schneider did form, in Paris, headquarters and a central office headed by salaried managers, but by different ways from those at United States firms which integrated mass production with mass distribution. As Schneider's growth behavior was different from that of the American big business, its organizational growth pattern also different.

1 0 0 0 OA 三井両替店一巻の会計組織

- 著者

- 西川 登

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.19, no.3, pp.28-57,ii, 1984-10-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

Early in the 18th century the House of Mitsui created a divisionalized administrative structure with a general office known as Omotokata in order to control many operating shops. By 1729, Mtsui's divisional structure came to consist of two major operating divisions-Hon-dana Ichimaki (the chain of silk fabric shops and a cotton fabric shop) and Ryogae-dana Ichimaki (the chain of exchange houses and silk commission houses). This paper focuses on the accounting systems in Ryogae-dana Ichimaki from 1729 through 1870.The research for this paper is based on many accounting reports that have survived and are preserved in the House of Mitsui Archives Collection at the Mitsui Research Institute for Social and Economic History (Mitsui Bunko), Tokyo.The structure of Mitsui under Omotokata resembled a divisional system as a whole, while Ryogae-dana Ichimaki may be characterized as a scaled down divisional structure. Each shop in Ryogae-dana Ichimaki had an independent accounting system, although Kyoto Ryogae-dana (Kyoto Exchange House) collected and distrubuted the residual profit of its affiliated shops.A part of the semiannual net income of the affiliates was set aside as reserves for their bad debts and building repairs. The residual profit of the affiliates was transferred to Kyoto Ryogaedana and added to its net income. A part of its total profit was set aside as reseves for its own bad debts and building repairs and reserves for employees' bonuses and retirement allowances of both its own and its affiliates.Although Omotokata was divided in a way like a spin-off of today in 1774, and reconsolidated in 1797, the accounting systems in Ryogae-dana Ichimaki were virtually unchanged till 1870.

1 0 0 0 OA 電力統制と五大電力経営者

- 著者

- 橘川 武郎

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.19, no.3, pp.1-27,i, 1984-10-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

The purpose of this paper is to examine several plans for regulating the electric power industry which were proposed by managers of five big electric power companies, Toho Electric Power Co., Tokyo Electric Light Co., Ujigawa Electric Power Co., Great Consolidated Electric Power Co. and Nippon Electric Power Co., in the 1920's and the 1930's. The managers mentioned in this paper are Yasuzaemon Matsunaga, Shohachi Wakao, Seinosuke Go, Ichizo Kobayashi, Yasushige Hayashi, Senzaburo Kageyama, Momosuke Fukuzawa, Jiro Masuda, Shinnosuke Arimura, Yoshizo Ikeo, Sataro Fukunaka, Kumaki Naito and Yoshijiro Ishikawa.The commonly accepted theory asserts that the managers of five big electric power companies devoted themselves to gain maximum profits at the expense of the public interests in those days, and that therefore the electric power industry was inevitably to be put under government control in 1938. The conclusion of this paper is, however, fairly different from those assertions. In reality the managers of five big electric power companies were relatively aware of the responsibility of public utility enterprises, and made efforts to supply plenty and lowpriced electricity. To give an example Yasuzaemon Matsunaga who was the vice-president of Toho Electric Power Co. announced Denryoku Tosei Shiken (the Private Opinion for Regulating the Electric Power Industry) in May, 1928, in which he emphasized the necessity of improving electricity service through introducing a new system. The so-called Denryoku Saihensei (the Reorganization of the Electric Power Industry) in 1950 was enforced according to this Matsunaga's opinion.

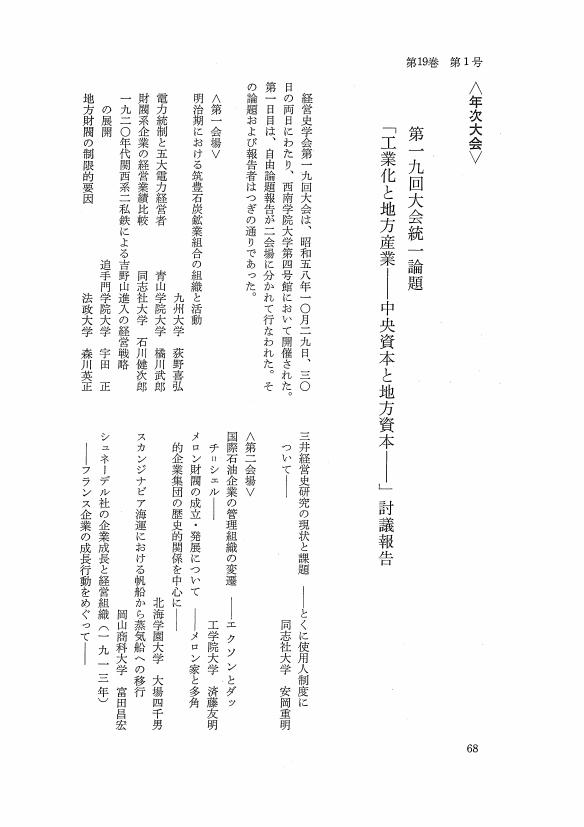

1 0 0 0 OA 第一九回大会統一論題「工業化と地方産業-中央資本と地方資本-」討議報告

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.19, no.1, pp.68-78, 1984-04-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

1 0 0 0 OA 明治期鉄道会社の経営紛争と株主の動向 -「九州鉄道改革運動」をめぐって-

- 著者

- 東條 正

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.19, no.4, pp.1-35,i, 1985-01-30 (Released:2010-11-18)

The kyushu tetsudo kaikaku undo (the Movement for the Reform in the Kyushu Railroad Company) was believed to have resulted from the dispute between Mitsubishi and Mitsui over the hegemony of the Kyushu Railroad Company. Both Mitsubishi and Mitsui were seeking control over the coal industry of the Chikuho region, and to obtain hegemony of the Kyushu Railroad Company was important, for it was the leading company in the transportation of coal in the northern Kyushu region. By examining the kyushu tetsudo kaikaku undo in detail, this paper illustrates that the primary cause of this movement was not the dispute between Mitsubishi and Mitsui but was far more complex. Also, this paper shows the problems in management of the privately owned railroad companies after the Sino-Japanese War.The aggressive policy of the Kyushu Railroad Company played an important role in the formation of the kyushu tetsudo kaikaku undo. The company was forced to take this aggressive policy because of two main reasons. First, the company was established on limited capital; and second, the industrial growth after the Sino-Japanese War placed a great demand on transportation. These forced the railroad companies to upgrade their facilities. This upgrading was supported by various companies involved in the coal industry that held stocks in the Kyushu Railroad Company, while other stockholders were not so eager to support such upgrading because of the decreasing profits. Particularly, it was the stockholders who hoped for the nationalization of the Kyushu Railroad Company and the bankers who held stocks in this company that became the main opponents for the executives of the Kyushu Railroad Company.

1 0 0 0 OA フランス企業者の対外活動 -第一次大戦前南ロシアにおける鉄鋼企業経営-

- 著者

- 堀田 隆司

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.18, no.3, pp.29-49, 1983-10-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

1 0 0 0 OA アメリカ精肉業における技術革新と企業構造

- 著者

- 塩見 治人

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.19, no.1, pp.1-26,i, 1984-04-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

The modern business enterprise resulted from the integration of mass production with mass distribution within a single business firm. The American meat-packing industry created the typical type of enterprise exemplified by the “Big Five” at the beginning of the 20th century. However, the dominant status of the “Big Five” has ceased today. The industry clearly represents the category of slight to negligible barriers to entry, and might be labeled as “low moderate” concentration. This paper focuses on the resolution process of “Big Five” business structure under long-term technological trends. Section II and III argue that differences in entrepreneurial response to the refrigeration age brought forth three types of business structure. Section IV raises and attempts to answer the question of the decline of the “Big Five.”

1 0 0 0 OA 大阪商船の労務対策と経営者

- 著者

- 小林 正彬

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.18, no.4, pp.1-36,i, 1984-01-30 (Released:2010-11-18)

O.S.K. (Osaka Shosen Kaisha), a small shipping company covering only the Inland Sea of Japan, was established in 1884. And it has been one of the two large shipping companies (O.S.K. and N.Y.K.) having the regular ocean routes since 1909.As compared with N.Y.K. (Nihon Yusen Kaisha), O.S.K. has achieved a great expansion under the good labor management and active strategies of leading executives.This article tries to clarify why O.S.K. could catch up with N.Y.K.. From the viewpoint of the labor management, there are four reasons : First, after Tokugoro Nakahashi took office as the fourth president of the company in 1898, he employed many talented college graduates as staff members. Second, the employees were well treated even in extreme depression. Third, this company had a more adequate system of Yobiin (the seamen reserved for sailing the regular ocean routes) than N.Y.K. did. Fourth, since captains and engineers of superior ability were promoted to executives, the labor and the management cooperated well with each other.This article emphasizes the last two of them : one is Yobiin system, the other is the good labor-management relations in O.S.K..

1 0 0 0 OA 一九世紀前半のイギリスにおける減価償却 -カヴァースヴァ製鉄所の事例-

- 著者

- 安部 悦生

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.19, no.1, pp.27-44,ii, 1984-04-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

From the viewpoint of accounting history, it is one of the great issues when and how systematic depreciation began. At the present time, an influential understanding on this matter might be that of A.C. Littleton, a renowned accounting historian. He maintained that systematic depreciation did not originate until the mid-nineteenth century when railway came up. By contrast, there is a different view that during the Industrial Revolution systematic depreciation already started. In this controversy, it is noteworthy that depreciation must be systematic and regular, not haphazard is assumed. Accordingly, depreciation by the inventory method is excluded from the discussion because it is not planned depreciation.The author tries to give some evidence to this problem by dint of looking into the accounts of the Cyfarthfa Ironworks which was the largest ironworks in Britain during the early nineteenth century. As a result of analysing these accounts, the following facts were found.In the Cyfarthfa ironworks, broadly speaking, the straight line method was adopted as a means of writing off “Premises”, from 1819 on. Although the way to write off “Premises” was rather complicated, it is obvious that they used the system so as to recover their invested fixed capital just when the lease contract regarding raw materials would expire. For that purpose, they set the length of 45 years to write off “Premises” in 1819. The process to discover this mechanism was kind of mysterious. In the long run, this fact-finding gives weight to the view that systematic depreciation started before the railway age by offering a fresh exemplification.

1 0 0 0 OA 日本紡績業における寡占体制の確立と後発紡績企業の成長戦略 -内外綿会社の事例-

- 著者

- 桑原 哲也

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.18, no.4, pp.64-92,iii, 1984-01-30 (Released:2010-11-18)

- 被引用文献数

- 1 1

The Naigaiwata Co. began the construction of a cotton spinning mill in Shanghai, China, in 1909. Operations began in 1911 as the first mill overseas of the Japanese cotton spinning industry.Naigaiwata entered into the Japanese spinning industry on a full scale in 1905, when it was in the final stage of forming oligopolistic structure. While Naigaiwata sold only a limited volume of cotton yarns in the oligopolistic domestic market, it relied heavily on export. This market strategy was successful during the booming era after the Russo-Japanese War.In 1908 the Chinese cotton yarn market tempoalily shrank under the depression and the devaluation of silver currency. Then Naigaiwata had to shift the main outlets from China to domestic markets. But this move resulted only in a poor financial situation.Facing this crisis Naigaiwata reconfirmed that it could not grow based on a domestic market alone. It was only overseas markets that Naigaiwata was given opportunities to penetrateintre.But the export strategy was not effective enough to establish a reliable status there. Naigaiwata then planned local production in China. It had a good position to accomplish this project as it not only had had business experiences in China but owned strong leadership in executing it. The local mill was so efficiently equipped to be competitive vis-à-vis the imported yarns from India and Japan.The overseas strategy of Naigaiwata was formulated as a creative response to the various constraints to the growth of those late comers under oligopolistic structure of the cotton spinning industry in Japan.

1 0 0 0 OA 両大戦間期日本不定期船業経営の一特質 -三井物産会社船舶部の定航問題-

- 著者

- 後藤 伸

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.18, no.4, pp.37-63,ii, 1984-01-30 (Released:2010-11-18)

In the Inter-War period, while “tramp shipping” was declining world-wide, Japanese tramp shipping developed remarkably well. This development was due to diversification in operating services, that was the development of “tramp linerization”.This is an analysis paper of the start of liner services and its development by tramp shipping enterprises-examining under what managerial environmental and cooperate strategies, this progress was made and maintained-through a case study of “MBK's Senpakubu” (Mitsui Trading Co's Shipping Div.) as a representative of the general merchant operator. The conclusions of this analysis are as follows : First the liner services by Senpakubu made a good start under circumstances in which there was suitable world-wide information and a trading network provided by the Bussan Co. But secondly, being an auxiliary unit of MBK's business, Senpakubu was requested to act on the whole organization's agreement in decision making, which sometimes reduced the strategic time horizon of Senpakubu's business. Thirdly, however, Senpakubu's strategy changed into soliciting a various or a wide range of different cargoes, loading more “Shagaini” (other shipper's cargoes) than “Shanaini” (its own cargoes) by steadily building a superior fleet, with which Senpakubu succeeded in new developments from an auxiliary unit into an autonomous functional operating unit within MBK's trades.

1 0 0 0 OA 相互銀行史の一考察 -無尽会社時代を中心として-

- 著者

- 麻島 昭一

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.19, no.1, pp.45-67, 1984-04-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

1 0 0 0 OA 大河内正敏における経営理念の形成 -貴族院議員としての活動を中心に-

- 著者

- 斎藤 憲

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.18, no.3, pp.50-68, 1983-10-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

1 0 0 0 OA 日本経営史における最大工業企業二〇〇社

- 著者

- 由井 常彦 マーク フルーエン

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.18, no.1, pp.29-57,ii, 1983-04-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

- 被引用文献数

- 1

The lists presented here are the data showing the financial records of the 200 largest enterprises in the development of Japanese business. These lists rank large industrial enterprises in the order of the size of the firm and also provide information on the amount of assets, paid-up capital and revenue of each of the enterprises.As the main purpose of this survey is a comparative study among industrialized countries, the lists are devised to the extent possible to be adaptable to international standards. (1) The enterprises listed are the 200 largest industrial enterprises, in accordance with the list of the United States and United Kingdom. (2) The authors researched the year 1918, 1930 and 1954. Although the data for the U.S. and the U.K. includes a list for 1949, marking the beginning of the post World War II period, the authors analyzing Japanese enterprises listed the 200 industrial firms of 1954 instead of 1949, because in 1949 Japanese large enterprises had not yet recovered from the war damage. (3) The standard for ranking enterprises in the lists is the sum of assets in real terms, mainly because most of the Japanese companies before World War II had not published their sales figures. (4) The definition and classification of “industry” is based on the SIC (Standard Classification of Industry) in the U.S.

1 0 0 0 OA 不況期の二大造船企業 -大正後期の三菱造船と川崎造船所-

- 著者

- 柴 孝夫

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.18, no.3, pp.1-28,i, 1983-10-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

After World War I, Japanese shipbuilding industry was visited by severe depression. At that time, most of shipbuilding firms in Japan were hard hit in their management by this depression. Mitsubishi Shipbuilding company and Kawasaki Dockyard Co., Ltd. were biggest ones in this industry at that time. But managements of these firms changed for the worse with the advance of the depression. Especially the condition of Kawasaki was severe. This company collapsed as early as the middle of this depression, 1927. On the other hand Mitsubishi was not so severe. Because, it was superior to Kawasaki in building of merchant vesseles. And it selected moderated policy for the depression.This company cut off unprofitable depertments and endeavored to accumulate internal funds. As a result, it could hold huge funds at the end of Taisho era. Policy of Kawasaki was very extreme compared of Mitsubishi's. This company tried to find a way out by extending to new fields one after another. But such policy imposed a big burden on the finance of this company.

1 0 0 0 OA 戦間期における企業の自主性と郵商提携問題

- 著者

- レイ ウィリアム D

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.18, no.2, pp.1-22,i, 1983-07-30 (Released:2010-05-07)

This paper deals with the plans for a merger between the N.Y.K. and the O.S.K. and the effects that the failure of the negotiations had on N.Y.K. management. Japan's large shipping companies were relatively independent of the zaibatsu to which they belonged. However, in the late 1920s and early 1930s several forces prompted Mitsubishi to take a more ieterventionist policy toward the N.Y.K. These forces included N.Y.K. managerial dissension and the financial problems of the depression. In particular Mitsubishi favored N.Y.K.-O.S.K. cooperation because it had developed close financial ties with the O.S.K., which had become a major market for its ships. Kagami Kenkichi, the leading financial executive within the Mitsubishi zaibatsu, tried to implement cooperation and merger with the O.S.K. during the early years of his tenure as N.Y.K. president. The principal focus of this paper is Kagami's attempt to negotiate this merger and the opposition that arose against it from “mainstream” N.Y.K. executives, that is, managers who had spent their whole careers with the company. These managers were more concerned with obtaining government subsidies and preserving the identity of their firm than with negotiations for the merger. Their successful opposition strengthened the forces of company autonomy.

1 0 0 0 OA オーストラリア経営古文書協会とメルボルン大学古文書館

- 著者

- 山中 雅夫

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.18, no.2, pp.66-72, 1983-07-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

1 0 0 0 OA 第一八回大会統一論題「両大戦間の日本海事産業」討議報告

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.18, no.1, pp.58-68, 1983-04-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

1 0 0 0 OA 第一次大戦前イギリスにおける大規模兼営保険企業の出現

- 著者

- 米山 高生

- 出版者

- 経営史学会

- 雑誌

- 経営史学 (ISSN:03869113)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.18, no.1, pp.1-28,i, 1983-04-30 (Released:2009-11-06)

- 被引用文献数

- 1 1

When we study the history of British insurance offices, especially in terms of comparative business history, it is paramount to consider 'composite' offices which handle various types of insurance -life, fire, marine and accident. There are no such insurance offices in the US, Germany, Japan and most other countries, but in Britain all major insurance offices, except a few, are large-scale composite offices.Composite offices, in the strict sense of the word, did not emerge until the turn of the century. During the years of 1904-14, some major insurance offices expanded their business by handling 'new-type' of insurance-personal accident, employers, liability, and so on-in addition to tranditional insurance. In other words, it was at this time that the British insurance offices undertook diversification of business.The purpose of this article is twofold. One is showing the process of the emergence of composite offices, and two, more importantly, presenting a picture of the historical character of British insurance business against the background of the maturity of the British economy. References used were the Board of Trade Returns and some insurance journals and yearbooks.The following are the conclusions of this article. Firstly, large-scale composite offices did not derive from life offices (e.g. Equitable, Standard Life), but from fire-life offices (e.g. Royal, North British and Mercantile) or fire-life-marine offices (e.g. Royal Exchange, Liverpool and London and Globe). Secondly, diversification, strictly speaking diversification to 'related business' according to R.P. Rumelt, was the result of amalgamations rather than internal growth. Furthermore, it was around this time that the post, of 'General Manager' emerged, bringing an 'Age of General Managers' to the British insurance business. Thirdly, traditional London based offices (e.g. London Assurance) and specialist life offices (e.g. Scottish Widows' Fund) continued to lose their shares in the insurance market. To the contrary, some active non-London insurance offices, which had a comparatively short history, gradually became of increasing importance.