16 0 0 0 OA 水死体をエビス神として祀る信仰 : その意味と解釈

- 著者

- 波平 恵美子

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.42, no.4, pp.334-355, 1978-03-31 (Released:2018-03-27)

This article discusses symbolic meanings of the belief in which a drowned body becomes deified as Ebisu-gami. Japanese fishermen usually are under a prohibition or a taboo that they should not take pollution caused by death into the sea, because they belive the sea is a sacred place and pollution, especially concerning death, might cause dangers to them. Nevertheless, they pick up a drowned body whenever they find it on the sea and deify it as Ebisugami, a luck-bringing deity. In Japanese folk belief Ebisu-gami is worshipped as a luck-bringing deity by fishermen, farmers or merchant and is also a guardian deity of roads and voyages. A remarkable attribute of Ebisu is its deformity. The deity is believed to be one-eyed, deaf, lame or hermaphrodical. It is also believed to be very ugly. People sometimes say that it is too ugly to attend an annual meeting of all gods which is held in Izumo, Simane Prefecture. In Japanese symbolic system deformity and ugliness are classified Into Kegare (pollution) category as I have represented in my articles (NAMIHIRA, E. : 1974 ; 1976). Some manners in Ebisu rituals tell that Ebisu is a polluted or polluting deity, e. g., an offering to the deity is set in the manner like that of a funeral ceremony, and after a ritual the offering should not be eaten by promising young men. Cross-culturally deformity, ugliness or pollution is an indication of symbolic liminality'. In this sense. Ebisu has characteristics of liminality at several levels (1) between two kinds of spaces : A drowned body has been floating on the sea and will be brought to the land and then be deified there. In Japanese culture, the land is recognized 'this world' and the sea is 'the other world'. A drowned body comes to 'this world' from 'the other world'. (2) between one social group and another social group ; In the belief of Japanese fishermen only the drowned persons who had not belonged to their own social group, i. e., only dead strangers could be deified as Ebisu. The drowned person had belonged to one group but now belongs to another group and is worshipped by the members ; (3) between life and death : Japanese people do not perform a funeral ceremony unless they find a dead body. Therefore, a person who drowned and is floating on the sea is not dead in the full sense. That is, the person is between life and death. The liminality of Ebisu-gami is liable to relate to other deities whose attributes are also 'liminal'. Yama-no-kami (mountain deity) or Ta-no-kami (deity of rice fields) and Doso-shin(guardian deity of road) are sometimes regarded in connection with Ebisu. Japanese folk religion is a polytheistic and complex one. Then, it is significant to study such Ebisu-gami that are interrelational among gods and have high variety in different contexts in the Japanese belief system.

15 0 0 0 呪術とは何か : 近代呪術概念の定義と宗教的認識

- 著者

- 髙山 善光

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 文化人類学 = Japanese journal of cultural anthropology (ISSN:13490648)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.83, no.3, pp.358-376, 2018

14 0 0 0 OA 物語の執筆と文化人類学 「連想の火」を熾すもの

- 著者

- 上橋 菜穂子

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 文化人類学 (ISSN:13490648)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.85, no.4, pp.583-601, 2021 (Released:2021-07-06)

- 参考文献数

- 25

本稿は、自らの物語執筆の過程をふり返り、文化人類学を学んできたことが、物語執筆と、どのように関わっているかを明らかにしようと試みたものである。 文化人類学と出会い、学び続けてきたことは、物語執筆に大きな影響を与えているはずだが、私はこれまで、そのことを、きちんと考えてみたことはなかった。学会賞をいただいたことを機に、初めて、真剣に自らの物語執筆と文化人類学の関係を考えてみたのだが、自分の思考の流れを追う作業は、近づくと消える逃げ水を追うようなもので、明らかにできなかった部分も多い。私にとって物語は「生み出すもの」であると同時に「生まれてくる」ものでもあり、執筆の過程には意識して行っている部分だけでなく、「自分の脳がなぜこういう動き方をしているのかわからない」と感じる部分が含まれているからである。 ただ、物語が生まれるきっかけとなる「いきなり頭に浮かぶ映像」が、実際の執筆に結びつくのは、特殊な「連想」が生じたときであり、火がついたように一瞬で広がっていくその「連想」には、私が文化人類学を学び、フィールドワークをしてきたことが深く関わっていることが見えてきた。人間の脳が物語を生み出す、ある意味普遍的な創作の過程に、個人の経験がどのように関わるか、わずかでも明らかにできているようなら幸せである。

14 0 0 0 OA 所謂足半(あしなか)に就いて〔豫報一〕

- 著者

- アチック ミウゼアム

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1, no.4, pp.710-768b, 1935-10-01 (Released:2018-03-27)

13 0 0 0 OA 客家と本地 : 香港新界農村部におけるエスニシティの一側面

- 著者

- 瀬川 昌久

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.51, no.2, pp.111-140, 1986-09-30 (Released:2018-03-27)

13 0 0 0 OA 震災復興とアニメ聖地巡礼者たち

- 著者

- 兼城 糸絵

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 日本文化人類学会研究大会発表要旨集 日本文化人類学会第47回研究大会 (ISSN:21897964)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- pp.88, 2013 (Released:2013-05-27)

本発表では、東日本大震災における津波によって被災した地域社会が復興へと歩みをすすめる過程においてアニメ聖地巡礼者たちが果たしてきた役割について具体的事例とともに考察していく。地縁血縁的枠組みに基づくローカルな組織でも災害復興を目指すアドホックな組織でもない、趣味に基づいて形成された組織が災害復興において重要な役割のひとつを担っていることを震災前後のコンテクストに基づいて明らかにする。

12 0 0 0 OA ケアの再構成を通した韓国の家族再考 : 既婚女性の乳がん患者の事例

- 著者

- 澤野 美智子

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 文化人類学 (ISSN:13490648)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.77, no.4, pp.588-598, 2013-03-31 (Released:2017-04-03)

- 被引用文献数

- 1

Studies on Korean families have discussed the role of Korean women caring for their families from the viewpoints of the patrilineal system, patriarchy and Confucian culture. They have looked at situations in which Korean women must care for their families in an environment of male supremacy situations, and stress the importance of the extended 'sidaek' family (i.e., the husband's parents, siblings and relatives). However, in situations where women become ill-although they once cared for their family, they now need caring themselves-or can or will not answer to the family's demands, the family members must change and reconstruct their respective roles of caring. In my research, I have clarified how women and their families in Korea reconstruct their caring by taking care of each other, as the women, who had been expected to care of their own families, face illness themselves. Women's breasts are symbols of sexuality and motherhood. In Korea, the breast is not only viewed as attractive and full of feelings, but also as the repository for negative feelings. In that country, too, there is a disease called 'hwa-byung,' which is a culture-bound syndrome caused by such accumulated negative feelings as anger or dissatisfaction. Korean people think that diseases, not just 'hwa-byung,' are caused by the accumulation of negative feelings in the body. Connecting those factors, they believe that the cause of breast cancer is an accumulation of negative feelings related to their families. Married female breast cancer patients in Korea, in particular, tend to connect the cause of their illness with the self-sacrifice caused by pressure from their husband or the extended 'sidaek' family. They recognize that the burden of caring they had borne was caused by self-sacrifice, and view it is as related to the cause of their illness. Therefore, they start to place more priority on their own desires, and come to value their own importance in family life, so as to cure their illness or prevent a relapse of the cancer. The women attempt to cure their disease through the act of 'hanpuli' (dispelling), namely, by expressing their feelings or doing acts of self-improvement that could not be carried out while they were busy caring for their families. They begin to involve their families in their 'hanpuli,' which in turn changes the nature of care in the family. The patients deal with their husbands and extended 'sidaek' family members in different ways. While their husbands must strive to help out with household chores and show more understanding, the patients avoid contact with their extended 'sidaek' family so as to reduce their stress. That may lead us to think that the women perhaps do not view their 'sidaek' relatives as part of the family. Such observations differ from the conclusions of past studies on Korean families, which have emphasized the importance of the extended 'sidaek' family. The family is reconstructed in such a way that positive support is given to each member of the family.

- 著者

- 間宮 郁子

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 文化人類学 (ISSN:13490648)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.77, no.2, pp.306-318, 2012-09-30

Japan has more in-patient days than any other country, as well as the highest number of beds in mental hospitals as a ratio of the total population. People with mental disorders used to be hidden away under the law, either in the medical or welfare system, and suffered from a social stigma. In recent years, however, mental patients have left such isolated medical institutions and started to live among the general community, not as psychiatric patients but as persons whose will is respected and who can get social-welfare support. As that drastic paradigm shift happened rapidly, Japanese institutions for persons with mental illness have come to design various support systems in response. This paper describes the experiences of several schizophrenic persons who utilize a social welfare facility in Hokkaido: Bethel's House in Urakawa, which has developed unique ideas about dealing with schizophrenic symptoms. The members of Bethel's House diagnose their own symptoms on their own terms, and are able to study their physical conditions, sensuous feelings, and mental worlds through their own experiences of living in the community. They carry out that work studies with friends - the other members of Bethel's House - and develop and train skills for communication with their friends and the rest of the real world. The paper looks at the case of a woman at Bethel's House who had difficulty holding down a job because of voices she heard and hallucinatory delusions she saw. She only realized that the voices and hallucinations might be coming from her own mind after talking with the other members of the house. Although she suffered from the voices, she gradually gained skills to communicate with her "friends." The staff members of Bethel's House did not try to ignore the voices, but instead were told to greet them (the "friends" were just the voices that she had heard). The staff members also urged her to try to experiencing talking with her friends using those greetings. Through such daily communications, schizophrenic persons at Bethel's House, such as this woman, learn to have specific physical experiences using their own words, thereby constructing practical communities. We also found that medical institutions and welfare facilities in Japan have kept away schizophrenic experiences, having removed patients from the community in the context of psychiatric treatment, responsible individuals, and human rights. In contrast, Bethel's House lets schizophrenic persons live with their voices and hallucinations, meaning that they live in a continuous world that includes both the hospital and the outside world. On the other hand, some residents in Urakawa Town wanted to exclude Bethel's House from the community because they felt it was accommodating "irresponsible" or "suspicious" persons, or subsidizing non-working people with public monies from the town budget. Although individual daily contact was maintained between Urakawa residents and the members of Bethel's House, those exclusionary attitudes against social institutions meant that Bethel's House has come to function as an asylum for schizophrenic people in such situations, increasing the feeling of isolation in schizophrenic persons' lives, both internally and externally.

11 0 0 0 OA 戦前の内蒙古におけるドイツと日本の特務機関 モンゴル学者ハイシッヒと岡正雄

- 著者

- 中生 勝美

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 日本文化人類学会研究大会発表要旨集 日本文化人類学会第57回研究大会 (ISSN:21897964)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- pp.B01, 2023 (Released:2023-06-19)

報告者は、1990年代から日本の人類学者の研究と調査の社会的背景を理解するため、関係者へのインタビュー、歴史アーカイブの渉猟、調査地への再訪などを通じて人類学史を研究してきた。今回の発表は内蒙古の特務機関の実態を紹介したうえで、ドイツのモンゴル学者ハイシッヒが、日本の特務機関と協力した罪で戦犯として裁かれた経歴があったこと、そして彼が岡正雄とウィーン大学時代に最も近い関係であったことを報告する。

- 著者

- 久保 明教

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 文化人類学 (ISSN:13490648)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.71, no.4, pp.518-539, 2007-03-31 (Released:2017-08-28)

1999年に販売が開始されたエンターテインメント・ロボット「アイボ」は、生活空間において人々の間近で動作する初めてのロボットとして多くの注目を浴びた。本稿では、アイボの開発と受容の過程を横断的に検討し、テクノロジーにおける科学的側面と文化的側面がいかなる関係を取り結ぶかについて考察する。科学およびテクノロジーを社会的ないし文化的事象として捉える研究は近年盛んになされてきたが、その多次元的な性質ゆえにテクノロジーを包括的に考察することには困難が伴う。本稿では、アイボという技術的人工物が科学的知識、工学的製作、日常的実践等の接点となっていることに注目し、異なる領域に属する諸要素が接続される様々な局面を分析することで、境界横断的なテクノロジーの動態を捉えることを試みる。そこで明らかになるのは、開発と受容の過程において、科学的要素と文化的要素が組み合わされる中でアイボの有様が方向づけられていったことである。開発過程においては、人工知能研究およびロボット工学上の成果である設計手法を基盤にしながらも、ロボットをめぐる人々の想像力に基づいた語りを工学的装置へと翻訳することによってアイボがデザインされていった。一方、受容過程においては、アイボ・オーナーの生活する空間に特有の日常的な事物の有様とアイボの機能システムの作動が結びつくなかで、アイボの動作が様々な形で解釈されるようになり、開発者の想定を超える意味をアイボは獲得していった。筆者は、開発者による工学的デザインとアイボ・オーナーによる解釈が科学的要素と文化的要素を組み合わせることで妥当性を生み出す営為であったと分析した上で、実在と意味を媒介するテクノロジーの働きにおいて科学と文化の相互作用が捉えられることを示した。

11 0 0 0 OA アイヌの農耕文化の起源

- 著者

- 林 善茂

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.29, no.3, pp.249-262, 1965-01-30 (Released:2018-03-27)

11 0 0 0 水死体をエビス神として祀る信仰 : その意味と解釈

- 著者

- 波平 恵美子

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:00215023)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.42, no.4, pp.334-355, 1978-03-31

This article discusses symbolic meanings of the belief in which a drowned body becomes deified as Ebisu-gami. Japanese fishermen usually are under a prohibition or a taboo that they should not take pollution caused by death into the sea, because they belive the sea is a sacred place and pollution, especially concerning death, might cause dangers to them. Nevertheless, they pick up a drowned body whenever they find it on the sea and deify it as Ebisugami, a luck-bringing deity. In Japanese folk belief Ebisu-gami is worshipped as a luck-bringing deity by fishermen, farmers or merchant and is also a guardian deity of roads and voyages. A remarkable attribute of Ebisu is its deformity. The deity is believed to be one-eyed, deaf, lame or hermaphrodical. It is also believed to be very ugly. People sometimes say that it is too ugly to attend an annual meeting of all gods which is held in Izumo, Simane Prefecture. In Japanese symbolic system deformity and ugliness are classified Into Kegare (pollution) category as I have represented in my articles (NAMIHIRA, E. : 1974 ; 1976). Some manners in Ebisu rituals tell that Ebisu is a polluted or polluting deity, e. g., an offering to the deity is set in the manner like that of a funeral ceremony, and after a ritual the offering should not be eaten by promising young men. Cross-culturally deformity, ugliness or pollution is an indication of symbolic liminality'. In this sense. Ebisu has characteristics of liminality at several levels (1) between two kinds of spaces : A drowned body has been floating on the sea and will be brought to the land and then be deified there. In Japanese culture, the land is recognized 'this world' and the sea is 'the other world'. A drowned body comes to 'this world' from 'the other world'. (2) between one social group and another social group ; In the belief of Japanese fishermen only the drowned persons who had not belonged to their own social group, i. e., only dead strangers could be deified as Ebisu. The drowned person had belonged to one group but now belongs to another group and is worshipped by the members ; (3) between life and death : Japanese people do not perform a funeral ceremony unless they find a dead body. Therefore, a person who drowned and is floating on the sea is not dead in the full sense. That is, the person is between life and death. The liminality of Ebisu-gami is liable to relate to other deities whose attributes are also 'liminal'. Yama-no-kami (mountain deity) or Ta-no-kami (deity of rice fields) and Doso-shin(guardian deity of road) are sometimes regarded in connection with Ebisu. Japanese folk religion is a polytheistic and complex one. Then, it is significant to study such Ebisu-gami that are interrelational among gods and have high variety in different contexts in the Japanese belief system.

11 0 0 0 OA ケニヤ海岸地方後背地における緩やかなイスラーム化 : 改宗の社会・文化的諸条件をめぐって

- 著者

- 菊地 滋夫

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.64, no.3, pp.273-294, 1999-12-30 (Released:2018-03-27)

- 被引用文献数

- 1

東アフリカ海岸地方後背地における緩やかなイスラーム化は, この地域に顕著に見られる憑依霊信仰と密接に関連している。しかし, すべての精霊が, それによって憑依された者にイスラームヘの改宗を要請するというわけではない。ある一群の精霊が他と比較して格段に強力かつ危険と見なされており, これらによって憑依された人々が, 心身の病状の悪化を避けるべく, 多少なりともイスラーム的な生活を送ることを余儀なくされるのである。他方, イスラームヘの改宗者たちのなかには, 病院における病気治療の失敗や, 学校教育からの疎外といった経験に言及する人々がいる。本稿では, カウマ社会における改宗者たちへの聞き取り調査に基づいて, 改宗の意味づけに一定のパターンを認めうることを示すとともに, イスラームヘの改宗が求められる憑依霊と, 病院や学校教育からの疎外という経験が相応する歴史的関係の一端を解きほぐすべく検討を試みる。

11 0 0 0 OA 日本見聞録について

- 著者

- 金 永鍵

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2, no.1, pp.54-69, 1936-01-01 (Released:2018-03-27)

11 0 0 0 日本民族学会研究倫理委員会(第 2 期)についての報告

- 著者

- 祖父江 孝男

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:00215023)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.57, no.1, pp.70-91, 1992-06-30

- 被引用文献数

- 1

10 0 0 0 OA パプアニューギニア・トーライ社会における自生通貨と法定通貨の共存の様態

- 著者

- 深田 淳太郎

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 文化人類学 (ISSN:13490648)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.71, no.3, pp.391-404, 2006-12-31 (Released:2017-08-28)

The Tolai people in the province of East New Britain, Papua New Guinea, have long used a form of shell money called tabu. They use that indigenous currency for various purposes: as "bride price," as a valuable shown and distributed in rituals, and as a medium of commercial exchange. These days, the provincial government is planning to recognize the tabu as the second legal tender in the province alongside the kina, which is the legal tender for all of Papua New Guinea. In this article, I will consider how these two currencies coexist and relate to each other, especially as media of exchange. Analyzing several practical cases of transactions, I will show that the relation between the two currencies falls into three patterns, as follows: (1) The two currencies are used for discrete transactions that differ in terms of the goods exchanged, as well as the situation, and so on. For example, only the tabu can be used as payment for initiation ceremonies into a secret society, and only the kina can be used in stores in town. They form different spheres of exchange that are exclusive to each other and have their own intrinsic value. (2) Either of the two currencies may be used for transactions that deal with the same goods in the same situation. In such transaction, both the tabu and the kina form a common standard of value via a fixed exchange rate. For example, in small village stores, various goods are valued under this single standard and are sold in both currencies. And these days, one can pay taxes, court fines and other fees at the government office using either of the currencies. (3) Besides pattern (2), this pattern involves the use of both currencies for the same kind of transactions, without necessarily maintaining a common value standard between the two. The use of both currencies takes place in an incoherent fashion for the exchange of exactly the same goods in the same situation. Transactions of this kind are typically seen by small vendors who deal in snacks and small goods used after a funeral. Patterns (1) and (2) can be understood as a single model, in which the tabu and kina keep their own separate spheres of exchange while maintaining an overlapping common area in each of their peripheries. In that common area, the two currencies are used together for various transactions under a fixed standard of value. But, at the same time, transactions according to those patterns keep the clear distinction between the two spheres of exchange. Meanwhile, this single model does not include the other pattern, pattern (3), in which the tabu and kina are used for similar transactions without having a common standard of value. That means that the two currencies can coexist and be used together, albeit incoherently, without adjusting the value through an exchange rate. As described above, the model that integrates patterns (1) and (2) is not consistent with pattern (3). But that is never an either-or situation. The relation between the tabu and kina in Tolai society is what allows these three inconsistent patterns to exist simultaneously.

- 著者

- 木村 秀雄

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 文化人類学 (ISSN:13490648)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.72, no.3, pp.383-401, 2007-12-31 (Released:2017-08-21)

- 被引用文献数

- 4

人類学は非常に厳しい環境の中にある。厳しい批評を受けて、民族誌という作品を書く力が減衰してしまっている。そのような状況の中で、批評が新しい民族誌の新しい方向性を切り開き、そこから生まれた新たな民族誌が再び新たな批評を生み出すという循環が成り立たなくなっているのだ。現在の世界を取り巻く状況を、世界無形文化遺産、特にボリビアの先住民であるカリャワヤを題材にして論じていく。そこから引き出せることは、世界無形文化遺産の制定は、危機にさらされた文化の保護を目的にしていて、そこで行われる活動は国際協力と似た性格を持つこと、職業的人類学者の書く民族誌は著作権を手放さない限り、究極的には人類学者の商売の道具であること、現地社会に調査の成果を還元するためには、無名の民族誌制作者として働くボランティアという立場もあるということである。そして最後に、複雑さをます世界の中で、民族誌の作成にも批評にも画一的な指針は存在しなくなっているが、そのことが逆に民族誌の自由度をますことにつながり、古いタイプの愚直な民族誌をも含め、民族誌の可能性は広がっていることが論じられる。

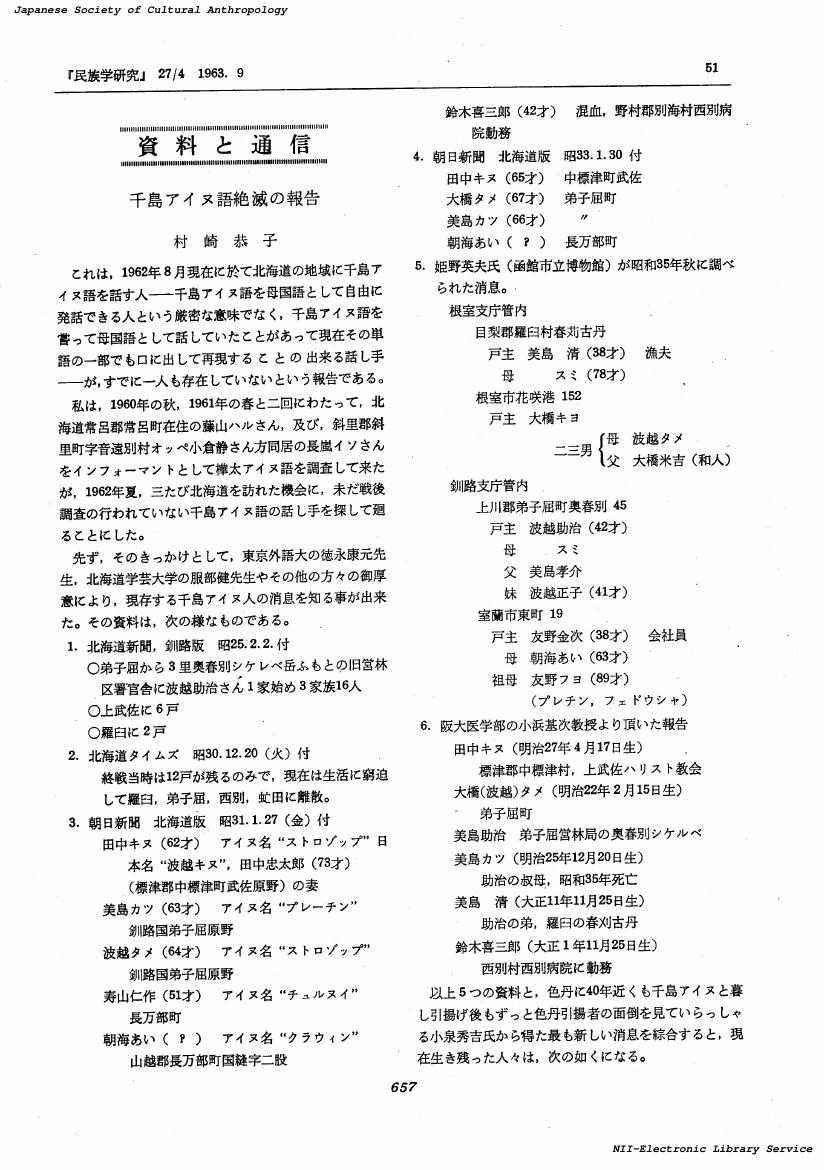

9 0 0 0 OA 千島アイヌ語絶滅の報告

- 著者

- 村崎 恭子

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:24240508)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.27, no.4, pp.657-661, 1963 (Released:2018-03-27)

- 著者

- 中野 惟文

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 日本文化人類学会研究大会発表要旨集

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2021, 2021

本発表では、現代カンボジア社会の呪術的実践の場において、呪術師の言葉や行為だけでなく、その場を囲んで実践を見守っているクライエントや見物人同士のコミュニケーションにも注目しながら、呪術のリアリティがどのように形成されるのかを明らかにする。

- 著者

- 内山田 康

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 文化人類学 (ISSN:13490648)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.73, no.2, pp.158-179, 2008-09-30 (Released:2017-08-21)

- 被引用文献数

- 1

アルフレッド・ジェルは、美学的な芸術の人類学の方法は行き止まりに突き当たると言った。それはどのような行き止まりだったのか。この行き止まりを超えることはどのようにして可能だとジェルは考えていたのか。このような疑問に突き動かされて本稿は書かれている。ジェルのArt&Agency(以下AA)を批判したロバート・レイトンは、ジェルが芸術の人類学を議論する時、文化や視覚コミュニケーションを重要視しない点を批判した。もしも見直す時間が残っていたら、ジェルは、このような点を書き改めたに違いないとレイトンは言う。レイトンはジェルの作品全体の中にAAを位置づけなかったから、このような仮定が立てられたのだろう。私はAAをジェルのより大きな作品群の中に位置づけなおして、ジェルの芸術の人類学が前提とした認識論へ接近しつつ、その芸術の人類学で重要な役割を果たした再帰的経路の働きと、図式の転移について考察する。