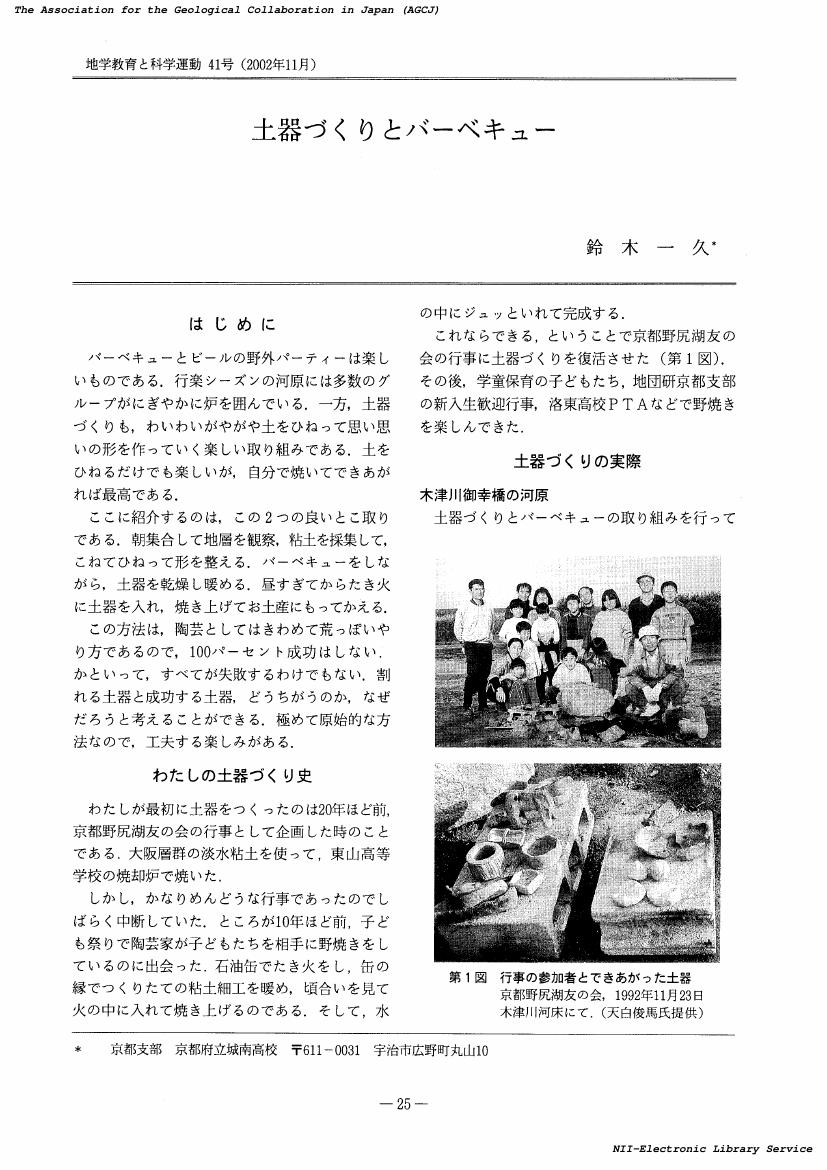

2 0 0 0 OA 土器づくりとバーベキュー

- 著者

- 鈴木 一久

- 出版者

- 地学団体研究会

- 雑誌

- 地学教育と科学運動 (ISSN:03893766)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.41, pp.25-28, 2002-11-05 (Released:2018-03-29)

- 参考文献数

- 8

2 0 0 0 OA 博物館活動に於ける土器作り教室の一事例

- 著者

- 吉川 金利

- 出版者

- 飯田市美術博物館

- 雑誌

- 飯田市美術博物館 研究紀要 (ISSN:13412086)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.17, pp.73-84, 2007 (Released:2017-10-01)

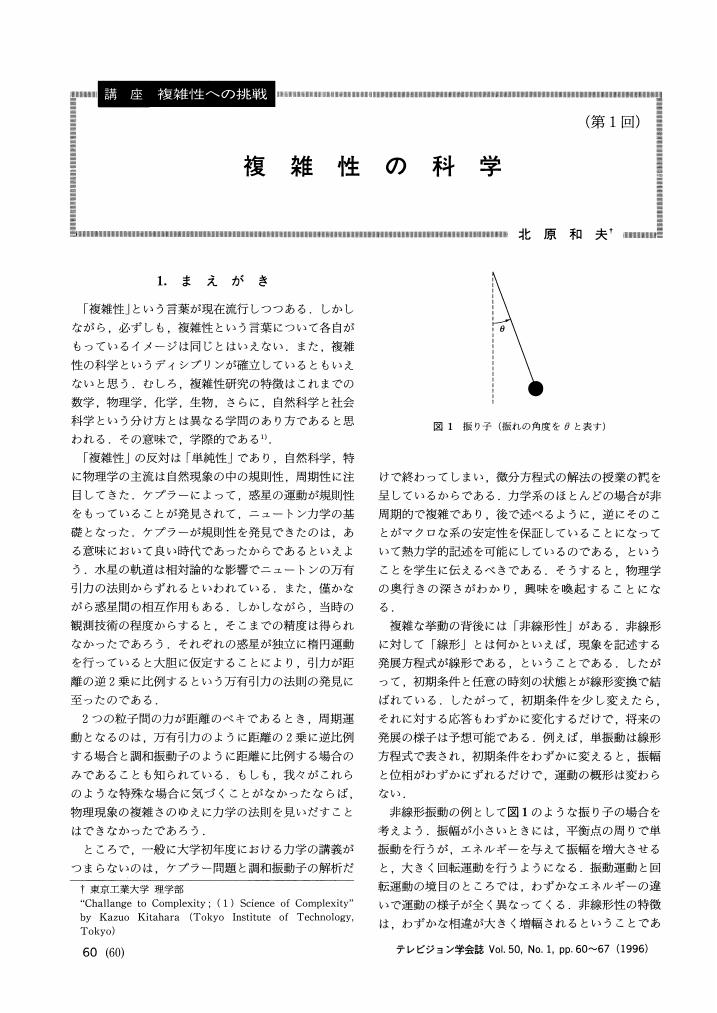

2 0 0 0 OA 複雑性への挑戦 (第1回) 複雑性の科学

- 著者

- 北原 和夫

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 映像情報メディア学会

- 雑誌

- テレビジョン学会誌 (ISSN:03866831)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.50, no.1, pp.60-67, 1996-01-20 (Released:2011-03-14)

- 参考文献数

- 21

2 0 0 0 OA U・ベックの「無知」の社会学 「戦略的無知」論に向けての展開可能性

- 著者

- 小松 丈晃

- 出版者

- 東北社会学研究会

- 雑誌

- 社会学研究 (ISSN:05597099)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.98, pp.91-114, 2016-05-30 (Released:2021-12-29)

- 参考文献数

- 34

何か否定的な含みを感じさせる「無知」は、これまで長らく研究テーマの中心に据えられてこなかったが、近年社会学でも、「環境」や「科学・技術」などを主題する論考の中に、(リスクや不確実性に加えて)「無知」や「ネガティブな知識」といった概念を軸にするものが増加してきている。本稿では、ベックのリスク社会論が、もともとこの「無知(Nichtwissen, non-knowledge)」を中心的な鍵概念にしていたところに着目し、このような近年の「無知の社会学」の展開に対するベックの貢献を確認し、「戦略的無知」論を展開していくための視点を模索する。まず無知の社会学の近年の広がりを確認したあと(一)、無知概念が多様な内実を有している点を指摘する(二)。ついで、同じ再帰的近代化論とはいっても、ベックとギデンズがいかに異なるかを検討し(三)、ベックによる無知論に立ち入って、「知ることができない」と「知るつもりがない」の対立を軸にした考察から、無知の三つの次元への整理にいたる議論の展開過程を追尾する(四)。最後に、ベック以後の無知論の展開可能性の一つとして、「戦略的無知」という観点のもつ意味について述べる(五)。

2 0 0 0 OA 『日本昆虫目録 第8巻 双翅目』の出版と日本産双翅目相の解明度について

- 著者

- 中村 剛之

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 日本昆虫学会

- 雑誌

- 昆蟲.ニューシリーズ (ISSN:13438794)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.19, no.1, pp.22-30, 2016-01-05 (Released:2019-04-25)

- 参考文献数

- 8

2 0 0 0 OA 札幌紳士録

- 著者

- 鈴木源十郎, 戸石北陽 編

- 出版者

- 札幌紳士録編纂会

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 1912

2 0 0 0 IR 法然の『往生要集』釈書の研究 : 『合』解釈と良忠の姿勢に注目して

- 出版者

- Elsevier

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 2019

2 0 0 0 IR 日本の牛肉輸出の現状と課題

2 0 0 0 IR モロッコにおける国民統合の土壌 -独立にいたる社会の変容とベルベル人

- 著者

- 岡田 洋平 大久保 優 高取 克彦 梛野 浩司 徳久 謙太郎 生野 公貴 庄本 康治

- 出版者

- 理学療法科学学会

- 雑誌

- 理学療法科学 (ISSN:13411667)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.24, no.1, pp.49-52, 2009 (Released:2009-04-01)

- 参考文献数

- 14

- 被引用文献数

- 1 1

〔目的〕本研究の目的は,Hoehn & Yahr(H&Y)3度以上のパーキンソン病患者において,pull testと過去1年間の転倒の有無との関係について検討することとした。〔対象〕本研究の対象は,H&Y 3度以上のパーキンソン病患者24名であった。〔方法〕評価項目はpull testと転倒歴とした。pull testと転倒との関連性について分析し,また,ROC曲線から転倒者を識別する上で最適なカットオフ値を設定した。〔結果〕転倒群は非転倒群と比較して、pull testのスコアは有意に高かった。pull testのスコアの1をカットオフ値にした際,転倒の有無を最も良好に識別可能であった(感度:94.7%,特異:60.0%)。〔結語〕pull testは,そのスコアの1をカットオフ値にすることにより,H&Y 3度以上のパーキンソン病患者の中から転倒の危険性が特に高いものを識別する上で有用な指標の1つとなる可能性が示唆された。

2 0 0 0 ジェネラリスト型行政職員像の再検討:学歴・ジェンダー・専門性

本研究の目的は、学歴やジェンダーが個人の職務経験(専門性)に及ぼす影響を解明することを通じて、ジェネラリスト型公務員像を再検討することにある。学術的独自性としては、30年間を超える長期間のデータセットを利用し、日本型雇用の転換期における公務員人事の変容を解明する点が挙げられる。長期間データによる人事分析は、民間部門にはトヨタを対象とする辻(2011)が存在するが、公共部門に関しては行われていない。画期的な大規模データセットを用いることで、大学進学率の向上や女性の社会進出などの日本社会の変動が、公共部門に与えたインパクトを分析可能となる。

2 0 0 0 OA 明治・大正期の演歌における洋楽受容

- 著者

- 権藤 敦子

- 出版者

- The Society for Research in Asiatic Music (Toyo Ongaku Gakkai, TOG)

- 雑誌

- 東洋音楽研究 (ISSN:00393851)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1989, no.53, pp.1-27,L4, 1988-12-31 (Released:2010-02-25)

This article examines the way in which the music imported from the West during the Meiji (1868-1912) and Taisho (1912-1926) periods, as well as music that was formed in Japan under its influence, was incorporated into the enka of those periods. By viewing the change in this music during this long period of almost fifty years, it also seeks to clarify one aspect of the reception of Western music by the general populace of Japan.The introduction of Western music, which began around the end of the Tokugawa and beginning of the Meiji periods, has since exerted a substantial influence on the musical culture of Japan. However, although considerable research has been undertaken with regard to the reception of Western music by official bodies such as the Ongaku Torishirabegakari (‘Institute for musical investigation’, affiliated to the Ministry of Education), the question of how the general public received this music is one that has gained little attention. Among reasons for this are, firstly, that there are limits in terms of research material since data of relevance are unlikely to be found in official records, and secondly, that the term “general populace” includes a variety of peoples of differing cultural and social backgrounds, thus making it difficult to deal with the reception of music by the general populace as a single category.Accordingly, to bring about a detailed understanding of the various modes of reception of Western music, it is necessary to clarify each of them in turn by approaching it from a variety of angles. An attempt has been made in this article to survey one aspect of the reception of Western music by the general populace by means of examining changes in the music of the enka sung by enkashi (enka performers) during the Meiji and Taisho periods, which met with wide popularity at the time.In its present usage, the word “enka” refers in general terms to popular songs of the kayokyoku genre that are said to have “Japanese” musical and spiritual characteristics. Originally, however, enka were used along with kodan (narrative) and shibai (theatre) as a means of transmitting the message of the Meiji-period democratic movement to the general populace in a readily understandable form. Songs sung by the proponents of this movement were known as “soshi-bushi”. Later, they were taken over by street performers who sang the songs while selling copies of their texts. This article takes as its subject popular songs beginning with soshi-bushi and continuing through to the beginning of the Showa period (late 1920's to early 1930's), when recordings of these songs began to be made commercially.At first, enka played an extra-musical role in catching the attention of the populace to transmit to them the message of the democratic movement. For this reason it lacked any fixed musical form. It possessed, rather, a musical transcience and topicality, in that it freely set texts about any event that captured common attention to music that happened to be popular at the time, such as minshingaku (Chinese music of the Ming and Qing dynasties), shoka (songs in Western style used in education), Asakusa Opera and the like. Anticipating the preferences of the masses, enka reflected their contemporary attitudes towards music, and were widely appreciated by them.In this research, 280 songs verified from among those actually identified as enka have been listed according to the chronological order in which they were popular, and each song has been transcribed and analysed. As a result, it has become possible to divide the period from 1888 to 1932 into three sections. These are: a) the first period, 1888-1903, centring on a group of related pieces using traditional techniques, based on “Dainamaitobushi”

2 0 0 0 OA 華厳思想と即身成仏(智山教学大会特別講演)

- 著者

- 竹村 牧男

- 出版者

- 智山勧学会

- 雑誌

- 智山学報 (ISSN:02865661)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.48, pp.1-25, 1999-03-31 (Released:2017-08-31)

2 0 0 0 OA 高崎直道先生を偲ぶ

- 著者

- 斎藤 明

- 出版者

- 日本印度学仏教学会

- 雑誌

- 印度學佛教學研究 (ISSN:00194344)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.62, no.2, pp.777-782, 2014-03-20 (Released:2017-09-01)

- 著者

- 宮武 賴夫

- 出版者

- 橿原市昆虫館

- 雑誌

- 橿原市昆虫館研究報告 (ISSN:24370029)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2, pp.1-9, 2023 (Released:2023-10-07)

2 0 0 0 OA 柳田国男の学問における方法について

- 著者

- 中嶋 昌彌

- 出版者

- 社会学研究会

- 雑誌

- ソシオロジ (ISSN:05841380)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.21, no.2, pp.74-84, 1976-06-30 (Released:2017-02-28)

2 0 0 0 OA 令和3 年度 飛鳥地域における昆虫相調査

- 著者

- 木村 史明 池田 大

- 出版者

- 橿原市昆虫館

- 雑誌

- 橿原市昆虫館研究報告 (ISSN:24370029)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2, pp.16-36, 2023 (Released:2023-10-07)

- 著者

- 真野 倫平

- 出版者

- 南山大学ヨーロッパ研究センター

- 雑誌

- 南山大学 ヨーロッパ研究センター報 = Bulletin of the Nanzan Center for European Studies

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.28, pp.1-11, 2022-03-31