148 0 0 0 OA 急性GVHDとTMA

- 著者

- 松本 公一 加藤 剛二

- 出版者

- 特定非営利活動法人 日本小児血液・がん学会

- 雑誌

- 日本小児血液学会雑誌 (ISSN:09138706)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.19, no.2, pp.90-95, 2005-04-30 (Released:2011-03-09)

- 参考文献数

- 18

血栓性微小血管障害 (thrombotic microangiopathy;TMA) は細小動脈を主体とする微小血管内皮障害に基づく虚血性, 出血性の臓器障害である.造血幹細胞移植の現場において, しばしば急性GVHDとTMAは混同され, 鑑別が困難な場合も少なくない.とくに近年, 消化管TMAという概念が導入されて以来, いっそう両者の境界は混沌としている.これは急性GVHDの診断基準が, TMAの存在を抜きにして設定されていることと, TMAの診断基準が明確でないことが影響しているものと考えられる. TMAの危険因子として, FK 506などの免疫抑制剤, 非血縁者間移植, HLA不適合血縁者間移植, ABO不適合移植, VODがあげられる.完成されたTMAの治療は困難であるので, 大腸生検などにより早期にTMAの存在を認識し, 過度の免疫抑制を控えることが移植成績の向上につながると考えられる.

6 0 0 0 OA 地域在住前期高齢者に対する運動プログラムの転倒予防に焦点をあてた費用対効果分析

- 著者

- 加藤 剛平 倉地 洋輔

- 出版者

- 日本理学療法士学会

- 雑誌

- 理学療法学 (ISSN:02893770)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- pp.11734, (Released:2020-08-04)

- 参考文献数

- 45

【目的】本邦における健常な地域在住前期高齢者に対する運動プログラムによる転倒予防の費用対効果を明らかにした。【方法】公的医療・介護の立場から分析した。質調整生存年数(Quality Adjusted Life Years:以下,QALY)を効果,医療費と介護費を費用に設定した。マルコフモデルを構築して,65 歳の女性と男性の各1,000 名を対象に当該プログラムを実施した条件における10 年後の増分費用対効果比(Incremental Cost-Eff ective Ratio:以下,ICER)を シミュレーション分析した。費用対効果が良好とするICER の閾値は5,000,000 円/QALY 未満とした。【結果】女性,男性集団のICER は順に1,550,900 円/QALY,2,277,086 円/QALY であった。【結論】本邦において,当該プログラムの費用対効果は良好である可能性が高いことが示唆された。

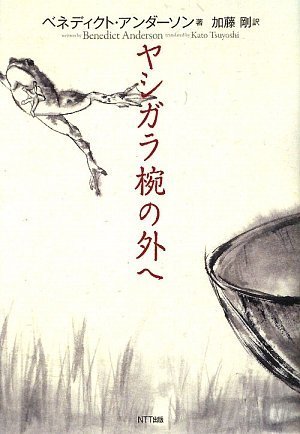

2 0 0 0 ヤシガラ椀の外へ

- 著者

- ベネディクト・アンダーソン著 加藤剛訳

- 出版者

- NTT出版

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 2009

- 著者

- 加藤 剛

- 出版者

- 京都大学東南アジア研究センター

- 雑誌

- 東南アジア研究 (ISSN:05638682)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.35, no.1, pp.77-135, 1997-06

この論文は国立情報学研究所の学術雑誌公開支援事業により電子化されました。

- 著者

- 加藤 剛

- 出版者

- 日本文化人類学会

- 雑誌

- 民族學研究 (ISSN:00215023)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.67, no.4, pp.424-449, 2003-03-30

開発の語られ方を、革命の語られ方との対比で検討する。舞台はインドネシアであるが、革命と開発は、第2次世界大戦後50年間のインドネシア現代史を二分するキーワードである。二つの社会的出来事についての語りを、リアウ州のコトダラム村(仮名)における過去20年ほどの定点継続調査の結果と、政府関係文書の記述などから比較・検討する。インドネシアにおける革命は、1945年8月17日の独立宣言から始まり、49年12月末の主権移譲まで、再植民地化を図ったオランダにたいする戦争、すなわち独立戦争を意味している。インドネシア初代大統領スカルノは、「指導される民主主義」時代(1959-65年)に、オランダが依然として支配していた西イリアンの奪回と、インドネシア式社会主義社会の建設を唱え、革命の復活・継続を叫んだ。しかし、1962年から63年にかけて西イリアン解放が実現すると、革命の説得力は色褪せ、経済の破綻や軍の画策もあって、政権は崩壊した。スカルノに代わって大統領となったスハルトは、32年間に渡って開発主義的政策を推し進めた。第1次から第6次まで立案・実施した5カ年開発計画のように、自己の権力も繰り返し更新可能と考えたのであろうが、長期政権下で汚職、癒着、縁故主義が蔓延し、1997年のアジア通貨危機の1年後、政権の座から滑り落ちている。革命と開発を比較するとき、前者は動員、参加・犠牲、体制打倒、記憶、再生(リプレー)と結びつき、開発は選挙、充足・消費、体制維持、計画、更新と結びつく傾向にある。革命は潜在的に危険であるがゆえに、一般に現存政権にとっては記憶されるべき過去であり続けることが望ましい。他方、開発は過去を振り向かない。プロジェクトの立案、すなわち、完成後いずれは自己陳腐化する非日常性を企画する開発には、自己更新の内的性向が組み込まれている。そして、開発プロジェクトとともに、予算、支出、充足、投票、さらにはしばしば汚職も同時に計画されるがゆえに、開発は権力と同じく内部から腐敗しやすい、といえよう。

- 著者

- 加藤 剛

- 出版者

- 京都大学東南アジア研究センター

- 雑誌

- 東南アジア研究 (ISSN:05638682)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.18, no.2, pp.222-256, 1980-09

この論文は国立情報学研究所の学術雑誌公開支援事業により電子化されました。

2 0 0 0 開発言説と公衆衛生:スリランカ,インド,インドネシアの事例研究

本研究の目的は、アジア諸社会において行われてきた公衆衛生に関わる社会開発の客観的・実態的把握に加え、政治的、社会文化的に構成され演出されてきた「清潔さ」「衛生」「健康」の関する語りやイメージを把握し、人々の社会開発をめぐる生活世界を解明することであった。そして、複数の社会での比較研究を通して、「開発現象」の共通性と個別性を明らかにすることを目指した。具体的には、(1)スリランカ、インド、インドネシアにおける公衆衛生プロジェクトの事例研究と、それに付随する様々な「開発現象」の学際的資料の収集、(2)開発言説を軸にした公衆衛生をめぐる新しい開発研究における枠組みの構築の2点であった。その結果、この3年間収集してきた資料は保健衛生に関わる開発プロジェクト、特に村落給水計画事業に関わるものであった。また、それと相前後して、調査のとりまとめに向けた理論的枠組みの再検討(アクター・ネットワーク論、サバルタン研究論)と、このような医療衛生研究の背景となる社会史的な資料の検討も行った。また、オランダに所蔵してあるインドネシアの医療史関係の資料も収集し分析した。ただし、とりまとめの研究成果報告書には、時間の関係で、村落給水事業の分析を十分に行うことは出来なかった。今後、村落給水計画に関する資料の整理を行い、開発言説と公衆衛生との関わりを論じていきたい。

- 著者

- 竹谷 浩介 高橋 正行 加藤 剛志 矢沢 道生

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 日本生物物理学会

- 雑誌

- 生物物理 (ISSN:05824052)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.44, 2004

- 著者

- 薄田 学 坂田 祐輔 山平 征二 春日 繁孝 森 三佳 廣瀬 裕 加藤 剛久 田中 毅

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 映像情報メディア学会

- 雑誌

- 映像情報メディア学会技術報告 40.12 (ISSN:13426893)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- pp.17-20, 2016-03-04 (Released:2017-09-22)

微弱な光により発生する光電子をアバランシェ増倍して出力する,電荷増倍型のCMOSイメージセンサを開発した.本イメージセンサは,低欠陥のシリコン基板内部に光電変換部と電荷蓄積部を分離して配置し,その間にp-n接合からなるアバランシェ増倍部を設けることで,光電子のみを10^5倍に増倍して読出し回路へ出力する構造を実現している.これにより,照度0.01luxの薄暗い環境下で自然なカラー撮像を実現した.また,印加電圧を制御して増倍率を調整することで,明るい環境でも暗い環境でも撮像を可能にし,ダイナミックレンジ100dBを達成した.本センサは,アバランシェフォトダイオード(APD)とトランジスタとを同一基板内に積層しており,APD搭載で世界最小3.8μm画素サイズのメガピクセルCMOSイメージセンサを実現している.

1 0 0 0 OA 成長期におけるソフトフード摂取がラット顎関節に与える影響

Modern people tends to have soft food . Therefore experimentalstudies have been performed to examine unfavorable influences to growth ofmasticatory muscles and craniofacial bone induced by such a dietary habits.The aim of the present study was to clarify the effects of soft diet on thetemporomandibular joint (TMJ) in growing rats using thehistomorphometrical and immunohistochemical methods. Twenty-four maleWistar rats were weaned at age 21 days and were divided into control andexperimental groups. Control rats were fed a solid food and experimentalones fed a liquid food from 1 to 8 weeks. After injection with5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU), the animals were perfused with 4%paraformaldehyde solution and the whole heads were removed. Serialcoronal sections of TMJ were stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin or withBrdU-immunohistochemistry. Three dimensions and the thickness ofcartilage layer of the TMJ were measured using histological sections, andcell proliferation in the TMJ was examined using immunostained sections.The height and width of the zygomatic process of mandibular fossa inexperimental group were smaller than in control group after 4 weeks. Thewidth and length of the condyle of experimental animals were also smallerthan those of controls after 4 weeks. In the mandibular fossa, articular zone(AZ) and hypertrophic zone (HZ) at 4 weeks and AZ and intermediate zone(IZ) at 8 weeks in the experimental groups were thinner than in the control.All zones at 4 weeks and AZ at 8 weeks of the condyle in the experimentalgroup were also thinner. The labeling indices of BrdU in IZ of themandibular fossa and of the condyle in the experimantal groups were lowerthan in the controls at 4 weeks and at 1 and 4 weeks, respectively. Thesefindings suggest that the soft food-intake inhibits the growth of the TMJ ofrats, due to low proliferative activity of cells in IZ.

1 0 0 0 OA 大理石骨病に伴った大腿骨転子下骨折の1例

- 著者

- 松下 優 前 隆男 佛坂 俊輔 加藤 剛 塚本 伸章 小宮 紀宏 清水 大樹 戸田 慎

- 出版者

- 西日本整形・災害外科学会

- 雑誌

- 整形外科と災害外科 (ISSN:00371033)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.65, no.3, pp.603-606, 2016-09-25 (Released:2016-12-06)

- 参考文献数

- 9

大理石骨病に伴った大腿骨転子下骨折の1例について検討することを目的とした.大理石骨病は骨変性を伴わない骨硬化性疾患で,主に破骨細胞の機能不全が原因とされ,骨硬化と骨脆弱性をきたし,易骨折性・造血障害・脳神経症状等を起こす稀な疾患である.骨折の際は,遷延癒合・偽関節・感染等の合併症を起こしやすく,また術中操作においても,骨質が非常に硬いため難渋する.症例は57歳 女性.自宅の階段で転倒し右大腿部を受傷.20歳頃に大理石骨病を指摘されたことがあり,大理石骨病に伴う病的骨折の診断で観血的骨接合術を施行した.術後15週に遷延癒合が見られ,再度骨接合術を施行した.術後1年間は免荷の方針としたが,骨癒合を確認でき,現在杖歩行でのリハビリ加療中である.

神経細胞網の発火,心拍,降雨,地震,金融商品の取引発生,店への客の来店など,さまざまな点過程データに共通に適用可能なデータオリエンテッドなモデル構築手法を開発するとともに,ひとつのモデルライブラリーとして蓄積した.また,適切なデータ取得に必要な実験計画,データ解析をトータルにサポートするソフトウエア環境の構築,時系列モデルとの関連性の研究も並行して進めた.本研究は,現象と数理モデルを結びつける道筋を明らかにし,その道筋つまりメタデータを蓄積し,支援環境として実現する一般的な研究計画の一環であり,特に点過程データに焦点を絞ったものである.ライブラリーは,クラスタリングのある点過程に対する汎用なモデル,隠れマルコフ点過程モデル,隠れ準マルコフ点過程モデル,混合点過程モデル,多変量点過程モデル,ゼロにリセットされたのち単調に増加する強度関数モデル,モデルそれぞれに関する最尤解探索離散化アルゴリズムなどからなり,その適用事例は,神経細胞の膜電位,心拍,降雨,地震発生,美容院来店,金融商品取引発生など多岐に渡る.また,モデル構築を容易にするための統合環境も構築した。本環境はDandDに基づくものであり,Textile Plotをはじめとするさまざまなデータヴィジュアリゼーション手法の充実が一つの特徴である.

1 0 0 0 7次対称方陣の数え上げ

- 著者

- 加藤 剛 湊 真一

- 雑誌

- 研究報告アルゴリズム(AL) (ISSN:21888566)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2019-AL-171, no.7, pp.1-7, 2019-01-22

7 次対称方陣とは,中心に関して対称な位置にある 2 マスの和が常に一定であるような 7 × 7 の魔方陣である.現在知られている 6 次の半魔方陣 (斜めの和の条件を持たない魔方陣) の数え上げの方法を参考にして,方陣を 2 つに分割して数え上げる手法を用いて計算した結果,7 次対称方陣の解の総数は,回転や鏡像で同じ形になるものを除いて,1,125,154,039,419,854,784 通りであることを初めて明らかにした.本稿ではその計算方法について述べる.

1 0 0 0 OA ジャカルタ都市圏の都市開発史に関する時系列可視化の手法および体系化

本研究は、世界で最大級のメガ都市の一つ、ジャカルタ都市圏(ジャカルタ、ボゴール、デポック、タンゲラン、ブカシ)を対象に、その形成過程において人為的な開発計画の変遷と具体的な土地利用の変化がどのように関係してきたかを明らかにする。また、世界中に分散するインドネシア・ジャカルタ都市圏の古地図や都市開発計画関連文献、写真・図表資料を収集・精査した上で、それを地理情報システム(GIS)によってデータとして比較可能な形式で統合化する。具体的には、1)開発動向の史的データの整備およびGIS化、2)インドネシアにおける「開発」概念の変遷、3)住宅地域開発の実態把握および都市政策の開発動向を明らかにした。

1 0 0 0 OA オランダ領東インド植民地都市の心象風景

- 著者

- 加藤 剛

- 出版者

- 京都大学東南アジア地域研究研究所

- 雑誌

- 東南アジア研究 (ISSN:05638682)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.35, no.1, pp.77-135, 1997-06-30 (Released:2018-01-31)

Many of the cities in Southeast Asia were created by colonial powers or transformed from forts, port towns or even villages to modern cities during the colonial period. From around the turn of the century they exuded a strong European atmosphere as attested by a comment and a drawing (Fig. 1) made by Osano Sase-o, a Japanese cartoonist who accompanied the Japanese troops invading Batavia in March 1942. How did the indigenous people perceive colonial cities, which were exogenous to Southeast Asia? This is the question I shall address here. In order to answer this question, specifically in relation to the Netherlands Indies, I review six novels, four published by Balai Poestaka and two by others, and try to glean common themes, topics, and expressions related to colonial cities. The six novels are Sitti Noerbaja—Kasih Ta'Sampai (1922) by Mh. Roesli, Salah Asoehan (1928) by Abdoel Moeis, Kalau Ta' Oentoeng (1933) by Selasi, Roesmala Dewi (Pertemoean Djawa dan Andalas) (1932) by S. Hardjosoemarto and A. Dt. Madjoindo, Student Hidjo (1919) by Marco Kartodikromo, and Rasa Merdika—Hikajat Soedjanmo (1924) by Soemantri. One reason why I chose these novels was that I had first editions at my disposal. As is exemplified by Sitti Noerbaja, there are sometimes marked differences between the first editions and the post-World-War-Two editions with respect to the usage or non-usage of terms and expressions evocative of the colonial period. Results of the review show that the six novels have few passages directly describing the characteristics of colonial cities. However, it is remarkable that they more or less exclusively use the same term kota to refer to cities and towns. In contrast, most writings in the nineteenth century use the term negeri or negri for this purpose, which means “country” and “region” as well as “city” and “town.” This shows, it is suggested, that indigenous people already shared the same term and similar ideas about cities and towns by the time these novels were written. Four themes or topics are gleaned from the six novels pertaining to images of colonial cities: love and “freedom”; the question of “I” or “saja”; modern education and administration; and clock time and western calendrical dates. The central theme of the novels revolves around love in the face of social convention and tradition. The hidden theme in this connection is freedom or merdeka. The story about the person who craves for the fulfillment of love, that is, freedom from social convention, is narrated in terms of “saja.” Other than Sitti Noerbaja, which generally uses “hamba” to describe “I,” the novels on the whole prefer “saja” to “hamba” or “akoe” in referring to “I.” It is argued that “saja” began to be used in the meaning of “I” by Europeans in translating European writings and stories into Malay and talking to the indigenous population in Malay. However, the Europeans tended to use “saja” only in talking to their equals or superiors; to their inferiors they tended to use “akoe.” The meaning of “saja” became more “democratized” as its usage spread among the indigenous population through schools, newspapers, political gatherings, meleséng (lectures and sermons) after Islamic Friday prayers, and so on. Behind freedom and “I” at the center stage of the novels, there stand two themes seemingly constituting the background of the novels' stories. (View PDF for the rest of the abstract.)

1 0 0 0 OA 精神科通院患者のカフェインに対する認識調査

- 著者

- 出川 えりか 安藤 崇仁 安藤 正純 加藤 剛 嶋村 寿 永田 あかね 村野 哲雄 林 広紹 馬場 寛子 齋藤 百枝美

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 日本医薬品情報学会

- 雑誌

- 医薬品情報学 (ISSN:13451464)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.20, no.3, pp.189-199, 2018-11-30 (Released:2018-12-08)

- 参考文献数

- 10

Objective: Caffeine may cause dependence and sleep disturbance, and interact with psychotropic drugs. Therefore, the caffeine intake of patients with mental disorders should be monitored. However, in Japan, there is no report on the effects of caffeine in mental disease patients or on their caffeine intake. Therefore, we conducted a questionnaire survey to clarify the perception of caffeine for psychiatric outpatients.Methods: We conducted an anonymous survey on caffeine recognition for outpatients at 8 medical institutions that advocate psychiatry.Results: We collected questionnaires from 180 people. The knowledge of foods containing caffeine tended to be high in those who had a positive attitude toward caffeine. More than 90% of those surveyed knew that coffee contains caffeine, but cocoa and jasmine tea were recognized by less than 25%. Of those surveyed, 39.4% consumed caffeine‐containing beverages at night. In addition, the rate of consumption of caffeine‐containing beverages tended to be higher at night because they had a positive attitude toward caffeine.Conclusion: The knowledge and intake situation of caffeine by patients with mental disorders differed depending on their interests and way of thinking about caffeine. As caffeine intake may influence psychiatric treatment, correct knowledge regarding caffeine is important.

1 0 0 0 OA 3D偏光フィルタ方式55インチ8K-3D IPS液晶ディスプレイ

- 著者

- 丸山 純一 桶 隆太郎 村社 智宏 石井 正宏 檜山 郁夫 加藤 剛久 梅澤 康昭 佐藤 達弥 高橋 通 山下 紘正 谷岡 健吉 千葉 敏雄

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 映像情報メディア学会

- 雑誌

- 映像情報メディア学会誌 (ISSN:13426907)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.72, no.10, pp.J136-J141, 2018 (Released:2018-09-26)

- 参考文献数

- 7

- 被引用文献数

- 1 1

3D偏光フィルタ方式を採用した8K-3D IPS液晶ディスプレイを開発した.近年,医療分野では,カメラとディスプレイにより医師の目をサポートする技術の開発が進んでいる.今回われわれは,立体視による奥行感の把握が可能な,内視鏡/顕微鏡手術向け「3D対応8K手術システム」の実現を目的に,3D偏光フィルタ方式8K-3D液晶ディスプレイの開発に取り組んだ.55インチ8K IPS液晶パネルの採用により,高精細,高画質な立体視を可能とした.手術室のレイアウトを考慮し,視距離1.0~1.5 mの範囲で使用することを目標に3D偏光フィルタを設計した結果,3D視野角8.6゜の範囲で3Dクロストークのない立体視を可能とした.本論文では,同ディスプレイの開発におけるポイントについて報告する.

1 0 0 0 OA 細菌性腸炎関連性腸重積症の1例

- 著者

- 前田 将宏 三浦 昭順 宮本 昌武 加藤 剛 出江 洋介 中野 夏子 比島 恒和

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 日本消化器外科学会

- 雑誌

- 日本消化器外科学会雑誌 (ISSN:03869768)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.43, no.5, pp.565-571, 2010-05-01 (Released:2011-12-27)

- 参考文献数

- 24

症例は23歳の男性で,インド旅行帰国後の下痢・腹痛・嘔吐を主訴に受診,CTにて回盲部腸重積症と診断し,同日緊急手術を施行した.術中所見では回盲部腸重積症を認め,用手的に整復が可能であった.しかし,盲腸は腫大し腫瘤様に触知され,周囲の腸間膜リンパ節の腫大も認められたため悪性病変も否定できず回盲部切除術を施行した.病理組織学的診断では,パイエル板の著明な肥厚と盲腸の鬱血・浮腫性変化を認め,非特異的腸炎の診断であった.後日,便培養からカンピロバクター(Campylobacter jejuni)および赤痢菌(Shigella flexneri)が検出され,細菌性腸炎関連性腸重積症と診断した.発生機序は回盲部の解剖学的要因に加え,急激な回盲部粘膜の炎症性変化に伴う先進部形成に腸管蠕動異常亢進が契機となったと考えられた.保存的治療の報告例もあり,細菌性腸炎が腸重積症の一因となることを認識し治療にあたることが肝要である.

1 0 0 0 OA レーザ光を用いた新しい顕微鏡

- 著者

- 小嶋 秀夫 多和田 昌弘 下山 宏 原田 匡也 加藤 剛

- 出版者

- 特定非営利活動法人 日本レーザー医学会

- 雑誌

- 日本レーザー医学会誌 (ISSN:02886200)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.20, no.4, pp.357-366, 1999 (Released:2012-09-24)

- 参考文献数

- 24

- 被引用文献数

- 1 1

通常の光学顕微鏡にはない特徴を備えた顕微鏡として,レーザ光を用いた新しい顕微鏡が各方面で注目されるようになってきた.本論文では,共焦点走査型レーザ顕微鏡走査型近接場光学顕微鏡光音響顕微鏡にっいて,それぞれの顕微鏡の動作原理,特徴ならびにいくっかの応用例を紹介する.同一試料を異なる測定法により同時に計測し,多方面から分析可能な複合装置の開発が,今後重要になるであろう.