- 著者

- 岩田 文昭

- 出版者

- 日本宗教学会

- 雑誌

- 宗教研究 (ISSN:03873293)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.81, no.4, pp.917-918, 2008-03-30 (Released:2017-07-14)

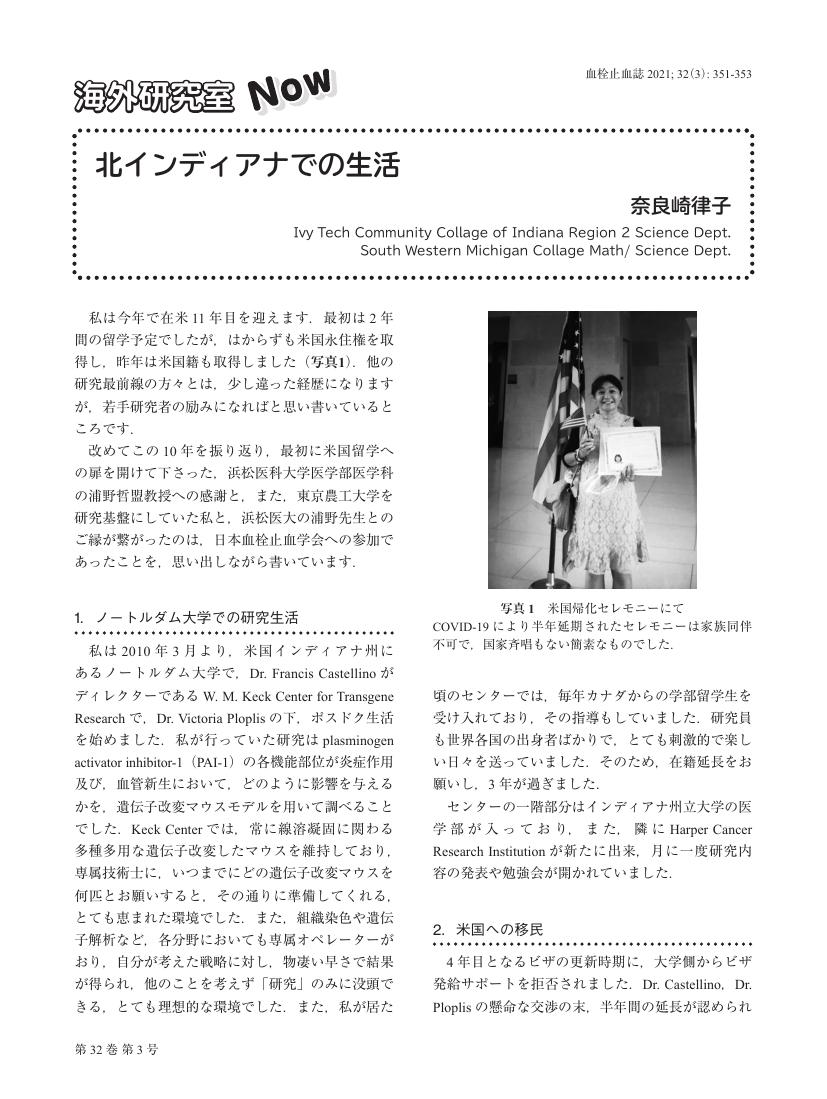

1 0 0 0 OA 北インディアナでの生活

- 著者

- 奈良崎 律子

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 日本血栓止血学会

- 雑誌

- 日本血栓止血学会誌 (ISSN:09157441)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.32, no.3, pp.351-353, 2021 (Released:2021-06-22)

1 0 0 0 OA 中国における後期中等科学教育の特色 ―化学教育課程を中心に―

- 著者

- 高 駿業 磯﨑 哲夫

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 日本理科教育学会

- 雑誌

- 理科教育学研究 (ISSN:13452614)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.62, no.1, pp.61-71, 2021-07-30 (Released:2021-07-30)

- 参考文献数

- 37

本研究では,中国の後期中等教育における2017年版の科学系教科の課程標準,特に化学課程標準の変容を分析し,日本の学習指導要領と比較することを通して,中国の課程標準の特色を明らかにすることを目的とした。まず,中国における「核心素養」を中心とした後期中等教育の教育課程に関する改訂の経緯を素描した。次に,後期中等教育における科学教育課程に関する改訂を概観し,導入された科学系の「教科の核心素養」を分析し,履修形態の変容を明らかにした。そして,2003年版の化学課程標準と比較し,2017年版の課程標準を分析した。最後に,中国と日本の比較を通じて,中国後期中等科学教育の特色を考察した。その結果,次のことが明らかになった。まず,2017年版の化学課程標準では,化学の学習を通じた理想的な生徒像や達成すべき目標が明確にされ,化学の目標がより具体化・深化し,内容もより構造化された。そして,現実の世界における問題状況や文脈,実験や探究活動がより重視されていることが明らかになった。また,日本と比較すると,中国の後期中等科学教育では物理,化学,生物が教科として独立しており,化学教育において,化学と社会や技術との関わりの学習では,積極的に参加する態度といった主に情意的側面が重視され,課程標準には教師の指導上のヒントが多く示されているのが特徴的である,と結論づけた。

1 0 0 0 OA バフンウニの苦味成分に関する研究(平成13年度日本水産学会賞奨励賞受賞)

バフンウニ(Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus)は,日本沿岸に広く分布し,主に福井県以南の日本海沿岸および九州地方で漁獲されている。美味なウニの一種とされ,すでに食用部分である生殖巣の呈味成分組成について明らかにされている。一方,東北地方では,バフンウニはほとんど漁獲対象とされていない。その主な理由は生殖巣にしばしば強い苦味を有するためとされている。本研究では,福島県いわき地方に生息する個体を対象とし,苦味の発現頻度を調べた結果,苦味が成熟した卵巣に特有なものであることに着目し,卵巣から新規含硫アミノ酸pulcherrimine [4S-(2'-carboxy-2'S-hydroxy-ethylthio)-2R-piperidinecarboxylic acid]を単離・構造決定した。さらに,pulcherrimine (Pul)の分析方法を開発し,生殖巣中の含量とその季節変化,さらにPulの味覚生理学的特性について検討した。本稿ではこれらの成果について概説する。

1 0 0 0 OA ヒスイ生成の謎に迫る:ストロンチウム・バリウム含有鉱物の合成実験からのアプローチ

ヒスイ輝石に共生する鉱物の合成実験から、ヒスイの生成条件をさらに絞り込もうというのが当初の目的であったが、試行錯誤を繰り返したあげくに合成実験が成功せず、結局は天然のヒスイの産状から生成環境を考察することに切り替えた。天然試料の観察においては、特に脈状ヒスイに着目して研究を行った。国内外各地からヒスイやその関連岩を切るヒスイ脈が報告されており、ヒスイの熱水起源説の根拠の一つとされている。これらのヒスイ脈では、ヒスイ輝石は脈の壁に対して垂直に伸長していることが共通の特徴であったが、兵庫県大屋地域から、脈に平行に伸長したヒスイ輝石結晶からなる脈状ヒスイを新たに見出し、その詳細な観察を行った。

1 0 0 0 IR 近世後期甲府における江戸相撲集団の興行形態

- 著者

- 齊藤 みのり

- 出版者

- 國學院大學大学院

- 雑誌

- 國學院大學大学院紀要 : 文学研究科 (ISSN:03889629)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.51, pp.85-106, 2020-02

- 著者

- 岸 泰子

- 出版者

- 日本史研究会

- 雑誌

- 日本史研究 = Journal of Japanese history (ISSN:03868850)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.700, pp.45-58, 2020-12

- 著者

- 岩城 卓二

- 出版者

- 兵庫県立歴史博物館ひょうご歴史研究室

- 雑誌

- ひょうご歴史研究室紀要 = Bulletin of the Historical Institute of Hyogo Prefecture (ISSN:24239534)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.5, pp.78-94, 2020-03

- 著者

- 田束 優 奥崎 智道 藤澤 彰

- 出版者

- 日本建築学会

- 雑誌

- 日本建築学会計画系論文集 (ISSN:13404210)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.768, pp.405-412, 2020-02

<p> This subject discussed reconstruction of the main shrine of "KATORI-Shrine" in Hananoi Kashiwa-city Chiba. The purpose of this subject is explaing about the professional ability of the master carpenter ''MASATOSHI MIMURA'' and the carver ''TSUNEHACHI ISHIHARA'' in construction of shrine and temple architecture used many decorations of building.</p><p> The main shrine of "KATORI-Shrine" was reconstructed in the fifth year of KAEI. It was needed a vast sum of money for the reconstruction and accomplished it forty year later including the years for fund-raising.</p><p> "MASATOSHI MIMURA" took the master carpenter and "TSUNEHACHI ISHIHARA" took the master carver, they participated in the construction with their clan. They decided the extent of contract work and worked in cooperation with each other. "MASATOSHI MIMURA" contracted to construct until the foundation of roof and the ground pattern of carving. "TSUNEHACHI ISHIHARA" contracted to carve lumber and make the carving for decorate wall board.</p>

1 0 0 0 寛文・延宝期における江戸の大工頭

- 著者

- 川村 由紀子

- 出版者

- 國學院大學

- 雑誌

- 國學院雜誌 = The Journal of Kokugakuin University (ISSN:02882051)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.121, no.8, pp.31-49, 2020-08

1 0 0 0 秀吉政権と東山大仏殿の造営 (小特集 東山大仏と豊臣政権)

- 著者

- 登谷 伸宏

- 出版者

- 日本史研究会

- 雑誌

- 日本史研究 = Journal of Japanese history (ISSN:03868850)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.698, pp.3-35, 2020-10

1 0 0 0 大仏瓦師福田加賀の柊原移転について

- 著者

- 中西 大輔

- 出版者

- 日本建築学会

- 雑誌

- 日本建築学会計画系論文集 (ISSN:13404210)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.777, pp.2419-2425, 2020-11

<p> The aim of this paper is to follow the tile craftsmen's relocation in Kyoto by researching documents in order to acquire historical data, track the technological lineage and reveal the contemporary social circumstances. This paper concentrates on a tile craftsman 'Fukuda Kaga' describing what his relocation in 1739 meant for the provision of roof tiles in Kyoto.</p><p> Several generations called Fukuda Kaga worked in the Daibutsu district, which was known as a major production area of roof tiles for temples and shrines. The term 'the tile craftsman in the Daibutsu district' can be found on many roof tiles and ridge tags.</p><p> It is known that the Fukuda Kaga were active from 1590 to 1735. They worked in Myoshinji-temple, Kyoougokoku1i-temple, Daitokuji-temple, and Kiyomizudera-temple. After 1735, their activities decreased significantly, and their course is unknown except for the last work in 1775.</p><p> Investigating <i>Hinamiki</i>, the diaries kept at Kamowakeikazuchi Shrine, I found records about his working activities m the Hiiragibara district in 1739. Being part of the Kamigamo district, t he Hiiragibara district was under the control of Kamowakeikazuchi Shrine. Therefore, Fukuda Kaga had to apply to the shrine for his work, and the shrine recorded his application in <i>Hinamiki</i>.</p><p> The following three points were revealed as a conclusion by deciphering:</p><p> 1. Fukuda Kaga moved to the Hiiragibara district in 1739, after he surveyed the geology of the area and selected a site for his workshop in 1738. Mentioning of Fukuda Kaga's name could be found before 1731 at Myoshinji-temple, and before 1735 at Daitokuji-temple. At Myoshinji-temple, a new tile craftsman applied to the temple for permission to open business in 1739, which was the same year Fukuda Kaga applied to Kamowakeikazuchi Shrine. At Daitokuji-temple, the name of a different new tile craftsman from another district could be found in 1780.</p><p> 2. A merchant named Yorozuya Kan'uemon at the Daitokuji-temple town mediated between Fukuda Kaga and Kamowakeikazuchi Shrine. At first, Yorozuya Kan'uemon applied for permission to open a tile shop to the shrine. After the permission was granted, Fukuda Kaga became the applicant, and Yorozuya Kan'uemon stood as a guarantor for Fukuda Kaga. It has to be noted that the application forms were prepared by Kamowakeikazuchi Shrine.</p><p> 3. The relocation of Fukuda Kaga was due to an agreement between himself and Kamowakeikazuchi Shrine. The main motivation for Fukuda Kaga to work in the Hiiragibara district was the great demand for a tile craftsman in the area, and the little competition. Contrary to this, the Daibutsu district was abundant in tile craftsmen in the same period consuming a great amount of the local clay. Furthermore, Kamowakeikazuchi Shrine needed him in order to overcome financial difficulties, because at the time, the shrine was indebted, and some of the priests were too poor to fix their own houses. They expected the tax revenues from Fukuda Kaga to solve these problems, and also to stabilize the lives of local farmers by giving them work.</p><p> In conclusion, Fukuda Kaga didn't close his workshop by An'ei era. Fukuda Kaga moved to the Hiiragibara district legally and based on his own intentions. After his relocation, new tile craftsmen started to work at the temples, where Fukuda Kaga had worked before. His move indicated the end of an epoch in the provision of roof tiles for temples and shrines in Kyoto.</p>

1 0 0 0 近世木地師の存在形態と地域社会

- 著者

- 斎藤 一

- 出版者

- 日本史研究会

- 雑誌

- 日本史研究 = Journal of Japanese history (ISSN:03868850)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.699, pp.31-47, 2020-11

- 著者

- 西坂 靖

- 出版者

- 三井文庫

- 雑誌

- 三井文庫論叢 = The journal of Mitsui Research Institute for Social and Economic History (ISSN:03898261)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.53, pp.263-297, 2019

1 0 0 0 三井同族の家業見習いに関する基礎的研究

- 著者

- 下向井 紀彦

- 出版者

- 三井文庫

- 雑誌

- 三井文庫論叢 = The journal of Mitsui Research Institute for Social and Economic History (ISSN:03898261)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.53, pp.187-245, 2019

- 著者

- 沢野 十蔵 池田 章 足利 正典 高野 健正

- 出版者

- 国際組織細胞学会

- 雑誌

- Archivum histologicum japonicum (ISSN:00040681)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.24, no.4, pp.369-386, 1964

In an investigation of the incidence of the sex chromatin of intermitotic nuclei in the various tissues (skin, stomach and muscle) of 37 human embryos (crown-rump length 7.9-318mm) and the ventral abdominal skin of 20 patients (10-80 years old), the following results were established.<br>1. In the early stages of 7.9-35.6mm crown-rump length (4-9 weeks), the sex can not be determined from the form of external genitals, without error, but it is possible to distinguish it from the incidence of the sex chromatin of intermitotic nuclei.<br>In the female embryos, the sex chromatin was identified in a comparatively high percentage of nuclei, and there are no marked differences of these percentages between the various tissues, as follows.<br>In the epidermis of skin: adj. (adjacent to nuclear membrane) 55.9%, free (free from nuclear membrane) 35.4%:<br>In the derma of skin: adj. 61.1%, free 18.6%.<br>In the gastric epithelium: adj. 55.5%.<br>In the gastric submucosa: adj. 57.1%.<br>In the striated muscle (premuscular cell): adj. 65.3%.<br>In the cardiac muscle (premuscular cell): 60.0%.<br>In the smooth muscle (premuscular cell): adj. 64.8%.<br>In the male embryos, the sex chromatin was identified in a comparatively low percentage of nuclei in each case, averaging 2.8% (0-7.6%).<br>2. The changes of incidence of the sex chromatin adjacent to the nuclear membrane with development are classified into the following three types.<br>Type 1. The incidence of sex chromatin scarcely changes during the prenatal and postnatal stages and is constantly about 50%, as seen in the epidermis of skin (cf. Fig. 1).<br>Type 2. The incidence of sex chromatin falls into a low percentage (to about 30%) at the middle of the fetal stage but afterward it does not change until the last stage, as seen in the gastric epithelium (cf. Fig. 2).<br>Type 3. The incidence of sex chromatin is about 50% at the middle of the fetal stage. Afterward, at the about 250mm stage (of 29-30 weeks) it falls into 30% or to a much lower percentage and then it does not change until the last stage, as seen in muscles (cf. Fig. 3).<br>3. In the germinal layer of skin in female embryos, the incidence of the sex chromatin free from the nuclear membrane is about 38.6% at the primary fetal stage, but afterward in the time of the middle or the last fetal sfage, it falls into a remarkably lower percentage (to 10.2-19.4%).<br>In the infant and adult stages, the incidence changes from 4.6% to 27.6%, but it has no correlation with the age factor. The incidence of this type gives some additional increases or decreases with the incidence of the sex chromatin adjacent to the nuclear membrane and so the particularly low samples of the incidence can not be found in the average (cf. Fig. 1).<br>4. It seems that, in each tissue, the period of declining of the incidence of sex chromatin has a correlation with that of the functional differentiation.<br>5. In the male, the incidence of sex chromatin is always in low percentage, and so it is possible to distinguish the sexual dimorphism from the incidence of sex chromatin. However, in the derma of skin and the gastric submucosa in the last fetal stage it becomes very difficult to distinguish the sexual dimorphism, because the incidence of sex chromatin in the female falls into a low percentage like the male (cf. Fig. 1).

1 0 0 0 幕末経済史再考:――手形取引の発展

- 著者

- 石井 寛治

- 出版者

- 日本学士院

- 雑誌

- 日本學士院紀要 (ISSN:03880036)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.74, no.2, 2019

The industrial revolution in Japan in the latter half of the 19th century, the first industrial revolution in Asia, did not depend on foreign capital until 1899, when the Japanese government called off the prohibition on foreign capital investment. This change was a result of Japanese law courts beginning to consider the crimes of foreigners in Japan.<br> Even after 1899, the amount of foreign capital used in private enterprises within Japan was unexpectedly small. In 1914, only 7% of all stocks and debentures of private enterprises were foreign-owned. How did Japanese entrepreneurs then raise money for industrialization?<br> Big enterprises raised money domestically through joint-stock companies. The stockholders invested not only their own money but also money borrowed from banks using their stocks as security. Most stockholders were merchants and financiers, including those who started their businesses in the Edo era. Although the loan business with the merchants set up by the biggest moneychangers, such as Mitsui and Kounoike, was said to be declining toward the end of the Edo era, it is notable that the draft business, which promoted modernization of the economy, was growing.<br> In Japan, payment to distant clients by bills of exchange began in the 13th century, and payment to nearby clients by such bills began in the 17th century. However, Japanese moneychangers did not develop a business around discounting bills because Japanese merchants did not use terminable promissory notes.<br> In this paper, I first discuss cases of settlement of transactions involving cotton goods and fertilizers between Owari (present-day western Aichi Prefecture) and Edo (present-day Tokyo) by bills of exchange. I also discuss cases of settlement for trade of cotton goods and tea between Yokohama and Kamigata (present-day Osaka and Kyoto) by bills of exchange. The latter cases were important in keeping foreign merchants from making inroads into Japan's market. It also led to Japanese merchants accumulating capital via cash payments with foreign merchants in Yokohama.<br> I then discuss cases of settlement among merchants by bills of exchange in Kamigata in the late Edo era. Such settlements became common in Osaka as well as its suburbs, thereby reducing the loan interest rate to approximately 6%, which was almost half of that in Edo.<br> In Osaka, bills of exchange could be settled by many moneychangers who were further controlled by the biggest moneychangers, particularly Kounoike, Mitsui, and Kajimaya. Contrary to popular belief that Mitsui was in financial straits by the end of the Edo era, the real situation of Mitsui was promising when the draft business was taken into account.<br> Although many moneychangers went bankrupt during the Meiji Reform, a considerable number of them survived the phase. Additionally, many powerful newcomers such as Chojiya, Nunoya, and Yasuda began operating during this period. Some of these moneychangers even established modern banks. The most important suppliers of capital for the industrialization in Japan were the merchants, both old and new, headed by moneychangers.

1 0 0 0 近世畿内の金融仲立人

- 著者

- 萬代 悠

- 出版者

- 吉川弘文館

- 雑誌

- 日本歴史 (ISSN:03869164)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.863, pp.20-38, 2020-04

- 著者

- 伊藤 裕久 濱 定史 小見山 慧子 山崎 美樹

- 出版者

- 日本建築学会

- 雑誌

- 日本建築学会計画系論文集 (ISSN:13404210)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.774, pp.1829-1839, 2020-08

<p> This paper seeks to clarify the transition of the townscape and the dwelling pattern of Shake-machi (Shinto priest town) of the Kasuga Taisha Shinto Shrine in the pre-modern times through the analyses of the Toma family's house which was built in the late 18th century and the existent archival materials from Toma family archives. We especially examined the formative process of the dwelling pattern of Negi (the lower-class Shinto priest) in Shake-machi during the Edo era, while paying attention to the difference before and after the Great Fire of Takabatake in 1717. The contents are as follows.</p><p> Introduction.</p><p> 1. Spatial composition and the dwelling pattern of Shake-machi at the beginning of the Meiji era.</p><p> The organization of the Kasuga Taisha Shinto shrine was constructed by the two hierarchies of the Shinto priest called Shake (the upper-class) and Negi(the lower-class). They lived in the north and south settlements separately. The north (Noda) declined, and the south (Takabatake) developed in the Edo era and 21 Shake and 93 Negi families lived in Takabatake in 1872. The houses of Negi were aligned along both sides of the main street there. Their dwelling lots of Tanzakugata-jiwari (Strip shaped land allotment) were divided into three types of the frontage dimensions (Narrow3ken/Middle5ken /Wide7-10ken). Middle and wide types accounted for most of their dwelling lots.</p><p> 2. Changing process of Shake-machi in the pre-modern times and its dwelling pattern.</p><p> In 1698, 30 Shake and 205 Negi families (double in 1872) lived in Takabatake and more over there were many Negi families which did not own their dwellings but were the tenants. Negi families did not only conduct exclusively religious services but also worked as actors, craftsmen and merchants like common people of the city. Therefore, the dwelling pattern of Negi was similar to Machiya (traditional town house of common people) style. Half of the Shake-machi was burned down in the Great Fire of Takabatake in 1717. Small Negi families without possessions or wealth were overwhelmed, and it was estimated that the new dwelling lots of a large frontage size increased by integrating their narrow dwelling lots after the Great Fire in 1717 and the new townscape with the dignity as Shake-machi was reconstructed by the sequence of the large frontage of mud walls and front gates along the street.</p><p> 3. Architectural characteristics of the house of Toma Family who was the Negi and its reconstructive study.</p><p> Toma family's house is surrounded by Tsuijibei (mud wall with a roof) with Yakui-mon Gate on its north side, and the main building has the large gable roof and Shikidai (the formal entrance). These features show the high formality of an influential Negi family. According to the reconstructive study, it was revealed that Toma family's house had been built in the late 18th century and the 2rows×3rooms plan with the earthen floor passage was originally the1row×3rooms plan connecting the lower ridge style Zashiki (2rooms). It resembles to the old Machiya of Nara-machi in the late 18th century. In this way, it is worthy of notice that Negi family's house had been developed from Machiya style by the reduction of small Negi families and the integration of their dwelling lots after the Great Fire of Takabatake in 1717.</p><p> Conclusion.</p>

1 0 0 0 江戸の音曲文化 (近世の一枚摺文化の受容と都市社会の研究)

- 著者

- 神田 由築

- 出版者

- 国立歴史民俗博物館

- 雑誌

- 国立歴史民俗博物館研究報告 = Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History (ISSN:02867400)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.222, pp.157-177, 2020-11