- 著者

- 北野 晃祐 浅川 孝司 上出 直人 寄本 恵輔 米田 正樹 菊地 豊 澤田 誠 小森 哲夫

- 出版者

- 公益社団法人 日本理学療法士協会

- 雑誌

- 理学療法学Supplement Vol.44 Suppl. No.2 (第52回日本理学療法学術大会 抄録集)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- pp.0997, 2017 (Released:2017-04-24)

【目的】筋萎縮性側索硬化症(ALS)患者の運動療法として,筋力トレーニングや全身運動が機能低下を緩和することが示されているが,ホームエクササイズの有効性の検証は皆無である。本研究では,ALS患者に対するホームエクササイズの効果を前向き多施設共同研究により検証した。【方法】国内6施設にて,神経内科医によりALSの診断を受け,ALS機能評価尺度(ALSFRS-R)の総得点が30点以上の軽症ALS患者19例を介入群とした。さらに,ALSFRS-Rの総得点が30点以上で,年齢,性別,初発症状部位,罹病期間,球麻痺症状の有無,非侵襲的陽圧換気療法の有無,ALSFRS-Rの得点,を介入群と統計学的にマッチさせた軽症ALS患者76例を対照群とした。なお,比較対照群は,同じ国内6施設において理学療法を含む通常の診療行為がなされた症例である。介入群には,理学療法士が対象患者に対して通常理学療法に加えて,腕・体幹の筋力トレーニングとストレッチ,足・体幹の筋力トレーニング,日常生活動作運動で構成したホームエクササイズを指導した。追跡期間は6ヶ月間とし,記録用紙を用いて実施頻度を記録した。安全性を確保するため,理学療法士が対象者の状況を1ヶ月ごとに確認した。主要評価項目はALSFRS-Rの得点とし,両群ともにベースラインと6ヶ月後に評価した。さらに介入群には副次評価項目として,Cough peak flow(CPF),ALS Assessment Questionnaire40(ALSAQ40),Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory(MFI)を,ベースラインと6ヶ月後に評価した。両群におけるベースラインと6ヶ月後の主要評価項目および介入群の副次評価項目を統計学的に解析した。なお,統計学的有意水準は5%未満とした。【結果】介入群のうち13名(68%)が介入を完遂した。脱落例は,突然死や転倒に伴う骨折および急激な認知症状悪化によるもので,ホームエクササイズによる有害事象は認められなかった。介入完遂例は全例が週3回以上のホームエクササイズを実施することができた。効果評価として,6ヶ月経過後におけるALSFRS-R総得点には,介入群と対照群に有意差は認められなかった。一方,ALSFRS-Rの下位項目得点では,球機能と四肢機能には両群間で有意差を認めなかったが,呼吸機能では両群間に有意差が認められた(p<0.001)。すなわち,6ヶ月後の介入群の呼吸機能得点は対照群よりも有意に高く,呼吸機能が維持されていた。また,介入群におけるCPF,ALSAQ40,MFIは,介入前後で変化は認められず維持されていた。【結論】障害が軽度なALS患者に対するホームエクササイズの指導は,安全性および実行可能性があり,さらに呼吸機能の維持に有効であることが示された。

1 0 0 0 OA 多様なNrf2活性化剤を活用した生体防御機構の適正な制御

- 著者

- 布施 雄士

- 出版者

- 筑波大学 (University of Tsukuba)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 2018

2017

1 0 0 0 OA バーゼル見本市とモスコーの時計工場

- 著者

- 菅沼 義方

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 日本時計学会

- 雑誌

- 日本時計学会誌 (ISSN:00290416)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.40, pp.67-74, 1966-12-01 (Released:2017-11-09)

1 0 0 0 OA 祝日考

- 著者

- 手塚 和男 Tezuka Kazuo

- 出版者

- 三重大学教育学部

- 雑誌

- 三重大学教育学部研究紀要. 人文・社会科学 (ISSN:03899241)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.46, pp.33-48, 1995-03-30

- 著者

- 飯田 都

- 出版者

- 日本教育心理学会

- 雑誌

- 教育心理学研究 (ISSN:00215015)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.50, no.3, pp.367-376, 2002-09

本研究の目的は,教師の児童認知だけでなく児童の教師認知を視野に入れ,学級適応感における児童の認知機能の役割に関して,探索的検討を行うことであった。教師-児童の関係性が明確であり,且つ教師の要請に関する認知の仕方の独自性が顕著であった児童4名を対象とし,彼らの教師の要請像の様相を検討した。その結果,(a)教師の要請に関する児童の認知が,自己高揚的であった場合,その児童は不得手とする要請に関しては,教師の否認による要請を過小評価し,一方,得手の要請は過大評価する。また,認知された方向づけは承認が中心である。(b)教師の要請について児童の認知が自己卑下的であった場合,当該児童は不得手な要請に関する否認による方向づけを過大評価し,得手の要請に関しては過小評価する。また,否認による要請の方向づけが強く認知されている,等の認知的特徴に関わる事例が報告された。これらの結果は,教師の要請に対する児童個々の要請認知のあり方が,学級適応感を規定する重要な要因であることを示唆するものであった。児童の学級適応感を理解する上で,教師の対児童認知のみならず,児童の教師認知要因をも考慮する必要性について考察した。

1 0 0 0 OA リハビリテーション科医が知って役立つ身体障害者手帳の診断書・意見書の書き方

- 著者

- 樫本 修

- 出版者

- 公益社団法人 日本リハビリテーション医学会

- 雑誌

- The Japanese Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine (ISSN:18813526)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.50, no.2, pp.130-135, 2013 (Released:2013-03-29)

- 参考文献数

- 10

- 被引用文献数

- 1 1

According to statistics from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare for the last ten years, the number of people with physically disabled persons' certificates increased from about 4,370,000 in 2001 to more than 5 million in 2008 and reached about 5,110,000 in 2010. The incidence of stroke and various internal diseases are increasing following an increase in lifestyle-related diseases and the development of Japan's rapidly aging society. In this social background, the physiatrist has many chances to write a physically disabled persons' medical certificate during the patients' care-planning. The most important point to consider is to understand the reason why the patient wants to get a physically disabled persons' certificate. Patients have several needs in their care-plan requiring a physically disabled persons' certificate such as financial aid for medical bills and travel expenses, and also for the cost or supply for orthosis, prosthesis and other technical aids for the disabled. The degree of invalidity must correlate with the medical findings and impairment in the medical certificate. For example the medical findings are the grade of paralysis, joint range of motion and muscle weakness, etc. Activities of daily living (ADL) provide the evidence of those findings and the degree of invalidity. The best practice when writing a medical certificate for physically disabled is that there must be no discrepancy between the medical opinion for the degree of invalidity and the medical findings, impairment and ADL of the patients.

1 0 0 0 OA 横浜中華街と神戸南京町ー東西チャイナタウン比較への試みー

- 著者

- 池田 和子 Kazuko IKEDA

- 雑誌

- 地域と社会 = Journal of region and society (ISSN:13446002)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.5, pp.123-152, 2002-08-01

- 著者

- 飯田 都

- 出版者

- The Japanese Association of Educational Psychology

- 雑誌

- 教育心理学研究 (ISSN:00215015)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.50, no.3, pp.367-376, 2002

- 被引用文献数

- 1

本研究の目的は, 教師の児童認知だけでなく児童の教師認知を視野に入れ, 学級適応感における児童の認知機能の役割に関して, 探索的検討を行うことであった。教師一児童の関係性が明確であり, 且つ教師の要請に関する認知の仕方の独自性が顕著であった児童4名を対象とし, 彼らの教師の要請像の様相を検討した。その結果,(a) 教師の要請に関する児童の認知が, 自己高揚的であった場合, その児童は不得手とする要請に関しては, 教師の否認による要請を過小評価し, 一方, 得手の要請は過大評価する。また, 認知された方向づけは承認が中心である。(b) 教師の要請について児童の認知が自己卑下的であった場合, 当該児童は不得手な要請に関する否認による方向づけを過大評価し, 得手の要請に関しては過小評価する。また, 否認による要請の方向づけが強く認知されている, 等の認知的特徴に関わる事例が報告された。これらの結果は, 教師の要請に対する児童個々の要請認知のあり方が, 学級適応感を規定する重要な要因であることを示唆するものであった。児童の学級適応感を理解する上で, 教師の対児童認知のみならず, 児童の教師認知要因をも考慮する必要性について考察した。

1 0 0 0 IR 明治期のカント

- 著者

- 宮永 孝

- 出版者

- 法政大学社会学部学会

- 雑誌

- 社会志林 = Hosei journal of sociology and social sciences (ISSN:13445952)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.67, no.2, pp.1-166, 2020-09

It was only after the Meiji Restoration (i.e. 1868), the start of a new government following the fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate, that the Japanese commenced to learn Western philosophy properly. But the Study of philosophy in Japan was primitive. Japanese had, however, only a few scholars who knew something about Western philosophy in the closing days of the Tokugawa government. Banri Hoashi (帆足万里, 1778~1851), the Confucian scholar and scientist, owned "Beginsels der Natuurkunde (The Principle of Physics), 1739" by Petrus van Musschenbroek. He could have found words "Wysbegeerte (i.e. philosophy)" or "Philosophie" by reading the preface of the book.Yōan Udagawa (宇田川榕庵, 1798~1846) was a person who studied Western sciences by means of the Dutch language and a researcher at the Bakufu's Institute for Western Learning in Yedo (nowadays Tokyo). He learned about "philosophia" and "metaphysica" by reading a handwritten copy of the "Seigakubon" (「西学凡」) by Giulio Aleni (艾儒略), an Italian Jesuit, in the Ming Dynasty. Rokuzo Shibukawa, (渋川六蔵,1815~51), the apprentice scholar at the Research Institute for Western Learning, translated the Dutch Words "philosofie" or "filosofy" into "費録所家".Amane Nishi (西 周, 1829~97), the apprentice scholar at the "Bansho shirabesho" (i.e. the Research Institute for Western Learning), had slight knowledge of Western philosophy presumably by reading "A Biographical History of Philosophy, 1845-1846) by G. H. Lewis. Prior to his departure for Holland in a bid for studying Western humane studies in the last days of the Tokugawa regime, he sent a letter, desiring to learn Western philosophy, to Prof. J. J. Hoffman at Leiden University, mentioning Descartes, Hegel, Kant etc. In Leiden, Nishi and his fellow student, Mamichi Tsuda (津田真道, 1829~1903), took private lessons under Prof. Vissering, studying mainly politics, economics and international law and so on for 2 years.While working for the new government after the collapse of the Tokugawa regime, Nishi ran a private school named "Ikueisha" (育英社) in Asakusa, Tokyo from 1870 to 1873, teaching his students about some Western philosophers and their theories. In his lecture he referred to kant's critique of cognition and his transcedental Reinen Vernunft as well. The name of Kant was expressed "韓圖" or "坎徳" in Chinese characters at that time.It has been almost 420 years since the Japanese started learning Western philosophy, however, it was suspended for centuries due to the ban on Christianity during the Tokugawa period. Tracing its introduction into Japan, we must go back to the time when Christianity found its way into our country in the 16 century. When Francisco Xavier (1506~53), the Jesuit missionary, and his followers landed in Kagoshima, Satsuma Province in 1549, the Japanese first learned about the ideas of Christianity and later on selected believers in the new religion started to study scholastic philosophy as well as Greek theology.Though we see lots of Portuguese or Latin words such as "Philosopho" or "philosophia" in the early Chiristian literature in Japan, we could not translate them into proper Japanese. Since we had no Japanese equivalent to them, missionaries were forced to use the original words.It was also at the Jesuit College at Kawachinoura (河内浦) in Amakusa-jima (天草島), a group of islands, west of kyūshū in the province of Higo, that Japanese theological students were first officially taught Western philosophy and Christian theology in 1599. The students then used Compendia compiled by the Spanish Jesuit, Petro Goméz in 1593 as their textbooks.Though Japanese Christians came in touch with Western ideas and lots of thinkers through Jesuit activities and books on Christianity, the newly started philosophical education in Japan broke down due to the ban on Christianity and to the national isolation promulgated by the Tokugawa government in the Yedo period (i.e. 17 century). But some of the scholars of Western learners in Japan had little bit of knowledge of Western philosophy in the dark age.Time flies. It was a German merchant named Carl Ernst Boeddinghaus (1834~1914) who brought the work by Kant to Nagasaki, Japan, in the 3rd year of the Bunkyu period (i.e. 1863). He purchased the second edition of "Antholopologie in programatischen Hinsicht abgefaßt von Immanuel Kant, 1797" in Germany, 1856, providing himself with this book on his trip to Japan. The book was found and bought in Nagasaki by Chōzo Muto (武藤長蔵, 1881~1942), a Professor at Nagasaki Higher Commercial School. Probably this was the first Kant book ever brought to Japan. Thus the German merchant played an important role in the propagation of German culture in Japan some 160 years ago.Nishi found not only Kant but called "philosophy" as "Tetsugaku" (i.e. 哲学) in Japanese. He enjoyed being named as an introducer of Western learning as well as Shigeki Nishimura (西村茂樹, 1828~1902), a bureaucratic scholar, in the early days of Meiji.Though Nishi sowed the field of German philosophy at his private school, the formal philosophical education in Japan began at Tokyo University founded in the 10th year of the Meiji period (i.e. 1877). Among "The Yatoi gaikokujin" (i.e. foreign employees) were found, Edward W. Style (1817~1870), an American Episcopolian, who first taught history and philosophy there.After him Ernest F. Fenollosa came and taught economics, politics, philosophy and sociology and so on the next year. He stayed in Japan for 8 years from the 11th year of the Meiji period (i.e. 1878) until the 19th year of the same. Fenollosa taught the philosophy of Kant in the second or third year class at the University. In succession to him, Charles J. Cooper (his age at birth and death is unknown), George W. Knox (1853~1912), Ludwig Busse (1862~1907) and Raphael von Koeber (1848~1923) taught German philosophy.Busse primarily used Kant's "Pure Reason" (Kritik der Reinen Vernunft, 1781) as a textbook whereas Koeber utilized "Critique of Judgement" (Kritik der Urteitskraft, 1790) and "Pure Reason" as texts.No essays or treatises on Kant were ever published from the early years of the Meiji period until about the 20th year of the same (i.e. 1868~1887) though, the periodicals and the public lectures contain only a slight mention of Kant. Books were silent on the philosophy of Kant.In November of the 17th year of the Meiji period (i.e. 1884), however a rare book titled "Doitsu Tetsugaku Eika" (『独逸 哲学英華』) written by Yosaburo Takekoshi (1865~1950), a historian and politician, was published by Hōkokudo in Tokyo. The author described the life of Kant and his theories using the German literature in the chapter of "Inmanyu Kantoshi" (「員蟆郵留韓圖子」) which extends over some 6o pages. This book is truly hard to read and a jargon though, it is the first essay on Kant in Japan.The first scientific essays or lectures on Kant began to appear from the start of the 20th year of the Meiji period (i.e. 1887) when the learned journal titled "Tetsugakukaizasshi" (『哲学会雑誌』) was published. From this time on the journal rendered great services in the philosophical world in Japan. It was in the mid-20th year of the Meiji period that scholars began studying Kant consulting the original texts. But their products were full of imitative nature wanting in originality. "T. T." an anonymous critic, commented on imitative tendency of Japanese academics.Rikizo Nakajima (中島力造, 1858~1918), a professor at Tokyo University, Enryo Inoue (井上円了, 1858~1919), the founder of the Tetsugakukan (nowadays Toyo University), Umaji Kaneko (金子馬治,1870~1937), a professor at Tokyo Senmongakko (nowadays Waseda University) began publishing their papers on Kant in the periodicals in the mid-20th year of the Meiji period (i.e. 1892-1896).In June of the 29th year of the Meiji period (i.e. 1896), Tsutomu Kiyono's "Hyochu Kanto Junrihihan kaisetsu" (『標註 韓圖純理批判解説』), commentary on Kant's "Kritik der Reinen Vernunft", was published by Tetsugakushoin in Tokyo. This was the first book on Kant published in the Meiji period. However it was criticized unfavorably saying it was merely refashioning of " Kant's Critical Philosophy for English Readers, 1889" by John P. Maffy D. D. and John H. Bernard B. D..From the 30th year of the Meiji period until the end of it (i.e. 1897 -1912), such scholars as Yoshimaru Kanie (蟹江義丸, 1872~1904), a professor at Tokyo Kotoshihan Gakko, Seiichi Hatano (波多野精一, 1877~1950), a lecturer at Tokyo Senmongakko, Masayoshi Marutomi (丸富正義, his age at birth and death is unknown), von Koeber (1848~1923), a professor at Tokyo University, Hajime Minami (三並良, 1867~1976), Takejiro Haraguchi (原口竹次郎,1882~1951), Wakichi Miyamoto (宮本和吉, 1883~1972), Yujiro Motora (元良勇次郎, 1858~1912) published their essays in different magazines. Remarkable research activities on Kant at the Tetsugakukan (哲学館) are worthy of notice because of the offering of correspondence courses.During the Meiji era (i.e. 45 years) only 20-plus essays and a commentary on Kantianism were published, though, the next Taisho period (i.e. 1912~1926), saw an explosive increase of publication on Kant in view of the Neo-Kantianism. Scholars took Kantianism as their own philosophy. At this point their studies on Kant deepened, however, they still showed a tendency to mimic habit. Some say that the Japanese are supposed to be naturalistic as well as positivistic by nature.German metaphysics does not suit their temperament. The slow advance of philosophy in Japan was due to the uncongeniality of disposition.Critics in the mid-30th of the Meiji period also pointed out our academical tendency of studying philosophy by imitation:scholars feel comfortable in receiving instruction from Germany. They always turn to others for assistance.

1 0 0 0 OA 中国及び韓国の市場品「神麹」における菌叢と含有成分の実態調査

- 著者

- 奥津 果優 門岡 千尋 小城 章裕 吉﨑 由美子 二神 泰基 玉置 尚徳 髙峯 和則

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 日本生薬学会

- 雑誌

- 生薬学雑誌 (ISSN:13499114)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.71, no.1, pp.41-48, 2017-02-20 (Released:2018-08-21)

- 参考文献数

- 20

“Shinkiku” is a traditional digestive drug prepared by the fermentation of wheat and some herbs with fermentative microbes. Shinkiku is manufactured in China and Korea, and also used in Japanese Kampo medicine as a component of Hangebyakujutsutemmato. However, there are currently no quality standards for shinkiku, and thus, the quality of shinkiku has considerable variation depending on its manufacturer. Although these variations would be partially derived from the differences in fermentative microbes, there are no studies about microbial diversities or chemical constituents in commercial shinkiku. Thus, we investigated the microbial diversity and chemical constituents of 15 commercial shinkiku samples to standardize its quality. PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of 16S rDNA and ITS1 sequences revealed that different microbes such as Lactobacillus sp. and Candida sp. were present in each shinkiku sample. On the other hand, most shinkiku samples showed amylase (12/15 samples) and lipase activities (9/15 samples) that behave as digestants. In addition, all samples commonly contained ferulic acid (>10 nmol/g), which has anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant activities. Thus, enzyme activities and ferulic acid were suggested to be one of the candidates for use as reference standards for the quality control of shinkiku. Exceptional shinkiku samples without enzyme activities showed a baked brown color, and ferulic acid content was inversely related with the brightness color of shinkiku (R2=0.47). Therefore, it seems that color indices would be effective to predict the quality of shinkiku such as enzyme activities and ferulic acid.

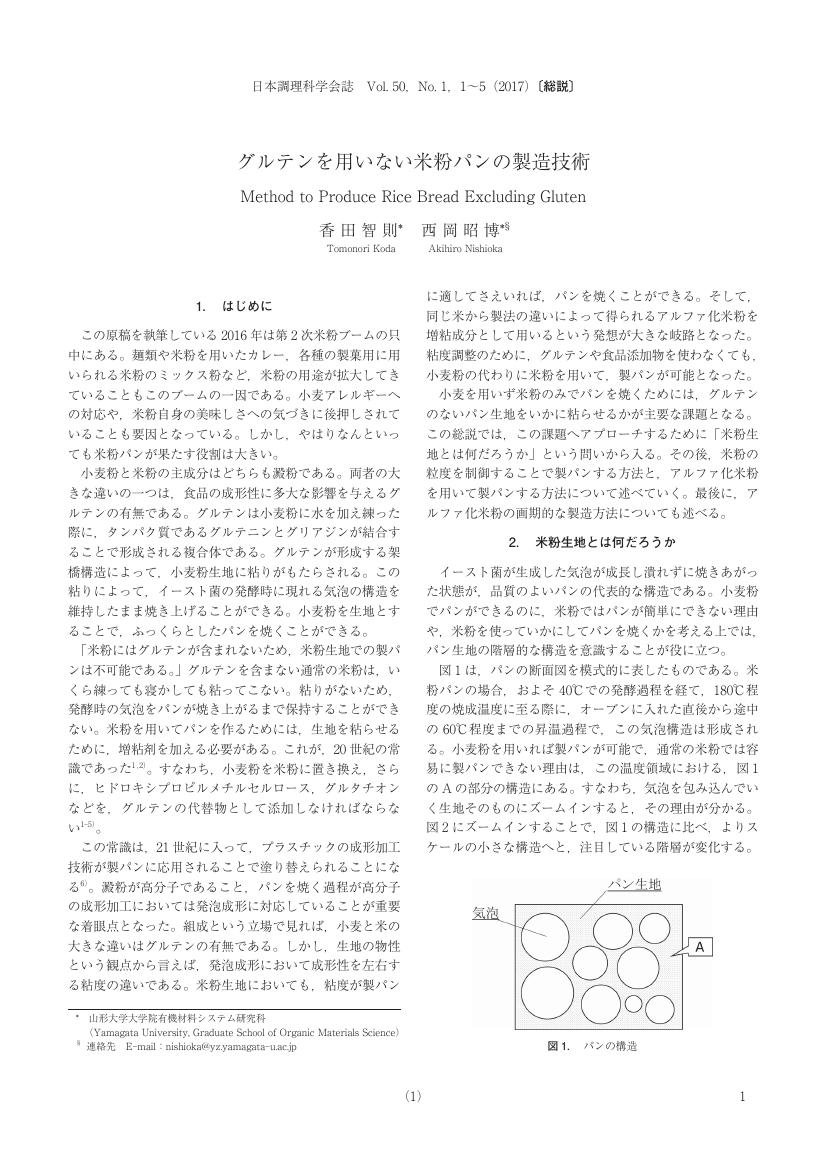

1 0 0 0 OA グルテンを用いない米粉パンの製造技術

- 著者

- 香田 智則 西岡 昭博

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 日本調理科学会

- 雑誌

- 日本調理科学会誌 (ISSN:13411535)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.50, no.1, pp.1-5, 2017 (Released:2017-02-20)

- 参考文献数

- 13

- 被引用文献数

- 2

1 0 0 0 コロナ禍の東京におけるオフィスの現状と今後の展望

- 著者

- 坪本 裕之

- 出版者

- 公益社団法人 日本地理学会

- 雑誌

- 日本地理学会発表要旨集

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2020, 2020

<p>2020年4月7日に,新型コロナウイルス感染症(Covid-19)の感染拡大防止を目的とした緊急事態宣言が政府より発せられ,全事業者への通勤者7割削減が要請された.多くの企業ではオフィスへの出勤制限とともに在宅勤務に切り替えられた.しかし5月の宣言解除以降,7割を超える企業が出社を前提とする体制に戻った.さらに再度の全国的な感染拡大を受けて,7月には再び出社抑制および時差出勤の推進が企業に対して要請された.今回のコロナ禍の特異性として,強制的な在宅勤務要請の期間の長さとともに,感染収束やワクチン開発の時期が想定できず,先行きに対する不透明さがある.東京のオフィスを取り巻く状況は非常に流動的である.</p><p></p><p> 2020年6月に企業のオフィスファシリティ担当者に対して,緊急事態宣言前後における働く場所についてのwebアンケート調査を行った.自社オフィスを中心として,自宅やサテライトオフィス,カフェなど働く場所の複数の選択肢があった宣言前に対して,宣言以降は感染防止のため,在宅勤務と時差出勤を含めたオフィス勤務に制約されている.</p><p></p><p> コスト削減を目的として,オフィス内でのモバイルワークを前提とするフリーアドレスの導入を検討している企業が増加し,加えて数年後には「ジョブ型」人事制度に切り替える企業事例が報道されている.しかし,このような就労環境を構築できるのは,ファシリティとICT,人事制度に精通した人材の存在と推進体制を組むことのできる企業である.加えて,成果主義を前提とした人事制度の策定にも,施策を進める時間が必要だ.</p><p></p><p> 対面接触によるコミュニケーションの強い制約も今回のコロナ禍の大きな特徴だ.多くの企業における現状の取り組みは,コミュニケーションの維持と出社比率のコントロールの間にあり手一杯の状況だ.在宅勤務が長い期間継続すれば,単純なオフィスワークの場としての意義を包含するオフィスを,対面接触の場に絞り再定義する可能性があり,住環境を補完するシェアオフィスも広域的に展開すると予測できるが,そもそも対面コミュニケーションの制約のもとでは,オフィスの意義やそれに伴う立地の変化が起こるとは考えにくい.</p>

1 0 0 0 OA 藤原定家による『百人一首』再解釈論:英訳を通して見る定家の解釈

- 著者

- オルショヤ カーロイ

- 出版者

- 同志社女子大学

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 2019-03-18

2018

1 0 0 0 OA 現行神社祭式

- 著者

- 進藤譲 編

- 出版者

- 愛治国学院学友会[ほか]

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 1924

1 0 0 0 OA 北アルプスにおける氷河・雪渓の環境条件

- 著者

- 山本 遼平 奈良間 千之 福井 幸太郎

- 出版者

- The Association of Japanese Geographers

- 雑誌

- 日本地理学会発表要旨集

- 巻号頁・発行日

- pp.100275, 2016 (Released:2016-04-08)

北アルプスの北部に位置する立山連峰は日本で唯一の氷河が存在する地域であるが,氷河の年間質量収支や形態,環境条件などは明らかにされておらず,例えば北アルプスの局所的に氷河が維持されている要因なども不明である.そこで本研究では,立山連峰における氷河の年間質量収支および,局所的に氷河と越年性雪渓が発達する環境条件を明らかにすることを目的として,現地調査や解析をおこなった.以下に研究方法と結果を示す. 1),立山三山に存在する御前沢氷河に対し,融雪期末期の氷河上および氷河周辺の位置情報を高精度GNSS測量により取得した.また,冠雪の2日前の2015年10月9日に北アルプス北部で小型セスナ機からの空撮を実施した.現地調査により得たGNSS測量データと空撮画像からSfMで氷河表面の25cm解像度のDEMを作成した.作成したDEMから算出した融雪期末期の御前沢氷河の平均表面高度は2637.7m,末端高度は2502.0mであり,面積は0.112km2であった.また,作成したDEMの精度検証のために現地のキネマティックGNSS測量データと比較をした結果,氷河全体の平均鉛直誤差が0.55mであった. 2),衛星画像と国土地理院の解像度10mDEMを用いて,北アルプス全域において主稜線から一定の距離にある点を流出点とする集水域を作成し,雪の涵養・消耗に関連する地形的要素を集水域ごとに比較した.解析の結果,北アルプスに現存する氷河はその周辺の谷地形よりも涵養に関わる要素の値が大きい結果が得られた.

- 著者

- 庄司 拓也

- 出版者

- 千葉・関東地域社会福祉史研究会

- 雑誌

- 千葉・関東地域社会福祉史研究 (ISSN:18821804)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.35, pp.9-25, 2010-12

- 著者

- 庄司 拓也

- 出版者

- 千葉・関東地域社会福祉史研究会

- 雑誌

- 千葉・関東地域社会福祉史研究 (ISSN:18821804)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.36, pp.1-17, 2011-12

- 著者

- 庄司 拓也

- 出版者

- 淑徳大学長谷川仏教文化研究所

- 雑誌

- 淑徳大学長谷川仏教文化研究所年報 (ISSN:09165827)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.35, pp.119-136, 2010

1 0 0 0 明治前期の東京感化院の家族制度 (特集 感化教育史研究の現在)

- 著者

- 庄司 拓也

- 出版者

- 淑徳大学長谷川仏教文化研究所

- 雑誌

- 淑徳大学長谷川仏教文化研究所年報 (ISSN:09165827)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.36, pp.59-84, 2011