91 0 0 0 OA 花粉飛散時における環境汚染物質の影響とアレルゲン物質の放出挙動

- 著者

- 王 青躍 ゴン 秀民 董 詩洋 関口 和彦 鈴木 美穂 中島 大介 三輪 誠

- 出版者

- 日本エアロゾル学会

- 雑誌

- エアロゾル研究 (ISSN:09122834)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.29, no.S1, pp.s197-s206, 2014-02-20 (Released:2014-04-01)

- 参考文献数

- 29

This paper reports on the absorption of environmental pollutants into various airborne pollen grains, aggravation of allergenicity, damage to the pollen cell walls, and the airborne behavior of fine allergenic particles, especially those released from Cryptomeria japonica (Japanese cedar) pollen, as abundantly determined on sunny days following rainfall. From the result of rainfall sampling and analysis, it was indicated that a great number of pollens were trapped in initial precipitation. At the same time, many burst pollen grains were also observed in the rainwater. Thus, it was possible that fine allergenic particles such as fractions of cell wall and contents of pollen were released from the bursting of pollen grains. On the other hand, elution of allergenic contents was increased when contacted with a weakly basic solution containing Ca2+ ions. Therefore, we think that one important factor contributing to the small-sized allergenic particles was induced by contact with rainfall after long-range transportation events of Asian dust.We succeeded for the first time in detecting fine allergenic contents containing 3-nitrotyrosine in urban atmosphere and clarified that 3-nitrotyrosine induces HeLa cell apoptosis. We summarized the various studies to elucidate the scattering behavior of various pollens, focusing on Cryptomeria japonica pollen and its allergenic particles in the urban atmosphere. This study has the potential for future developments in palynology.

5 0 0 0 OA 境界を内破する ─キャリル・チャーチル『トップ・ガールズ』における身体

- 著者

- 鈴木 美穂

- 出版者

- 西洋比較演劇研究会

- 雑誌

- 西洋比較演劇研究 (ISSN:13472720)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.13, no.2, pp.108-119, 2014-03-31 (Released:2014-04-03)

This paper discusses Caryl Churchill’s Top Girls by focusing on the portrayal of Angie, who is regarded by critics as a comparatively minor character. As symbolically exhibited in the confrontational relationship between Marlene and Joyce, a binary opposition functions as the dominant structure of the play. Marlene, one of the leading characters, is bent on boosting her already successful career and espouses Margaret Thatcher’s monetarist policies. Appearing in almost every scene, she seems to be at the heart of the play, and her presence reinforces various dichotomies, such as winner/loser and centre/margin. Her sister Joyce, a working-class single mother, does not accept Marlene’s point of view. However, Angie, who has been raised by Joyce but is actually Marlene’s sixteen-year-old daughter, has the potential to decentralise Marlene’s position and subvert the rigid binary opposition. First, Angie demonstrates the possibility of fluidising binary relationships at various levels. In Act II scene 2, she and her friend Kit are crammed into a small shelter. Their interdependent relationship is shown through the representation of their bodies, as when Kit shows her menstrual blood to Angie on her finger, and Angie licks it. These representations also symbolize the variable relationship between the inner and outer parts of the body. In that scene, Angie is geographically and socially in the most marginalised position in relation to the centre, London, where Marlene lives. However, Angie decides to visit London because she believes that Marlene is her birth mother. In this manner, Angie is able to break up the rigid relationship between the two. Second, the unrealistic dinner party in the first scene can be thought of as Angie’s dream, which also overthrows Marlene’s centrality within the play. Although the party is held to celebrate Marlene’s promotion, her position is gradually decentralised as guests talk about their painful experiences in childbirth and separation. The separation between mother and child suggests a strong connection to Angie’s search for her biological mother. During the dinner party, verbal language gradually recedes as the characters’ bodies come to the fore. These processes are symbolically represented by the portrayal of the female pope, Joan, whose vomiting in the final scene evokes the story of her horrible childbirth. These images also imply the plasticity of the relationship between the inner and outer parts of the body, as suggested by Angie’s bodily representation in the shelter scene. Thus, Angie implodes the various boundaries and decentralises Marlene’s position in Top Girls.

- 著者

- 福田 武司 船木 那由太 倉林 智和 秋山 真之介 鈴木 美穂

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人電子情報通信学会

- 雑誌

- 電子情報通信学会技術研究報告. OME, 有機エレクトロニクス (ISSN:09135685)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.112, no.333, pp.29-32, 2012-11-28

周囲のpHで発光強度が変化する有機色素と半導体ナノ粒子の蛍光共鳴エネルギー移動を利用したpHセンサーは、次世代の診断材料として幅広い用途での展開が期待される。ここで、半導体ナノ粒子には可視光の発光や低い毒性という特徴を有しているInPを用いることが、今後の用途展開を考える上で重要となってくる。本論文では、高効率で赤色領域での発光を示すInP/ZnSナノ粒子蛍光体を作製するために、高いバンドギャップを有するZnS層のソルボサーマル法を用いたコーティング条件(前駆体溶液のpH)を最適化して、25.1%のフォトルミネッセンス量子効率を得た。また、このInP/ZnSナノ粒子蛍光体の周囲にpHに対してフォトルミネッセンス強度が変化する5-(and-6)-carboxynaphthofluorescein, succinimidyl esterを結合させることで、InPからの蛍光共鳴エネルギー移動による発光を確認した。さらに、InPと有機色素のフォトルミネッセンス強度比はpHによって変化することを確認し、pHセンサーとして機能することを実証した。

2 0 0 0 プロゾーン現象って何ですか?

- 著者

- 鈴木 美穂

- 出版者

- 医学書院

- 雑誌

- 検査と技術 (ISSN:03012611)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.44, no.13, pp.1272-1274, 2016-12-01

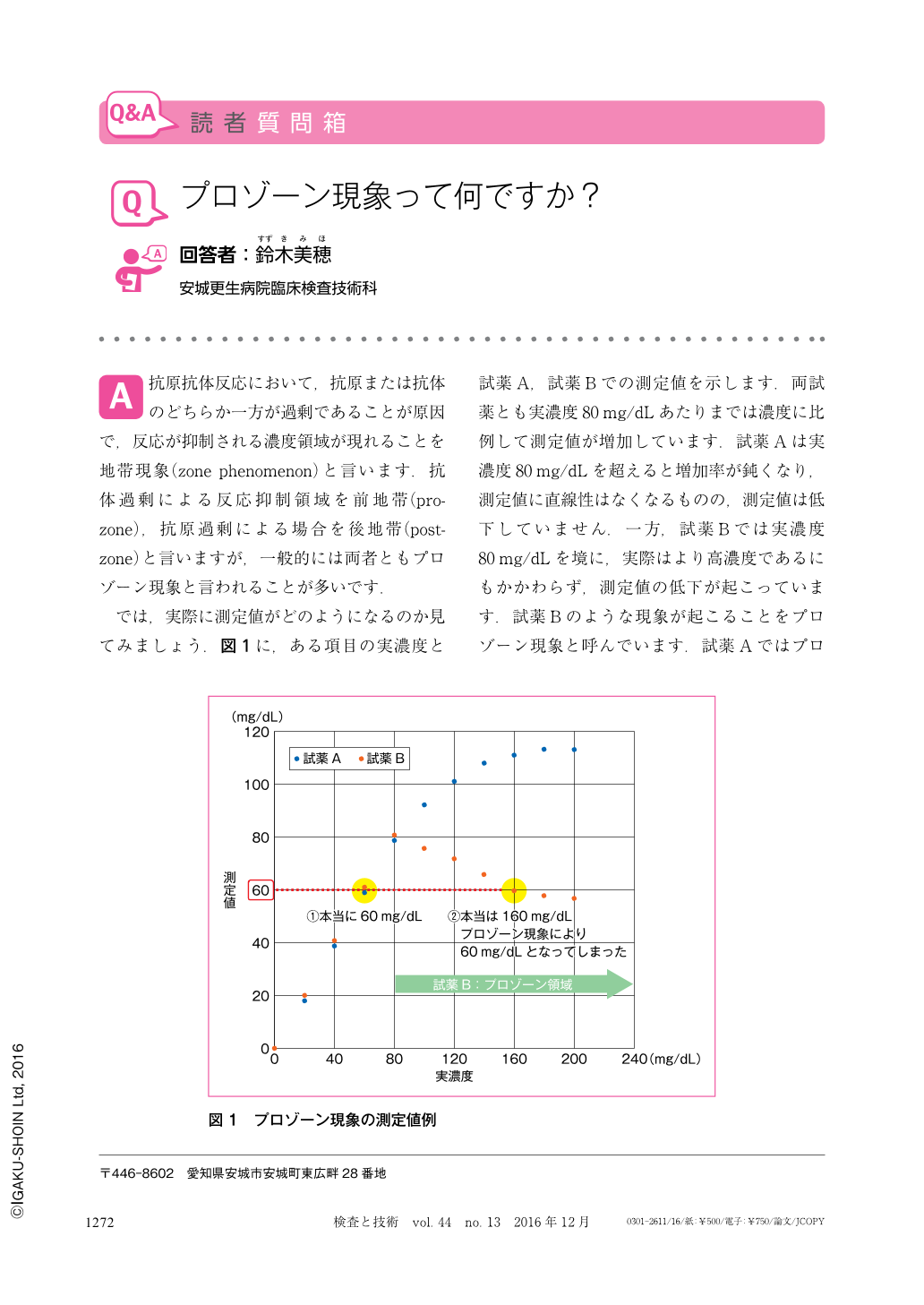

Q プロゾーン現象って何ですか? A 抗原抗体反応において,抗原または抗体のどちらか一方が過剰であることが原因で,反応が抑制される濃度領域が現れることを地帯現象(zone phenomenon)と言います.抗体過剰による反応抑制領域を前地帯(prozone),抗原過剰による場合を後地帯(postzone)と言いますが,一般的には両者ともプロゾーン現象と言われることが多いです.

本研究では、日本において高度実践看護師のひとつであるナースプラクティショナー(NP)を欧米のように活用した医療提供モデルを構築するために、日本におけるNP養成課程修了者の実践の実態を明らかにし、NPの実践による費用対効果等のアウトカムを評価する。医療技術の進歩と医療ニーズの複雑化により医療者がますます不足かつ偏在する中で、欧米諸国では医療の質とアクセスを一定に保つために、NPを活用してきているが、日本ではNPは公式には認められておらず、協議会ベースでの認定であり、公的導入に至るには科学的にも政策的にも支持するエビデンスがほとんどなく、日本での医療保険制度でのエビデンスの生成を目指す。

1 0 0 0 OA 新規多発性筋炎モデルマウスに対するIL-1阻害療法の検討

- 著者

- 杉原 毅彦 沖山 奈緒子 渡部 直人 鈴木 美穂子 宮坂 信之 上阪 等

- 出版者

- 日本臨床免疫学会

- 雑誌

- 日本臨床免疫学会総会抄録集 第36回日本臨床免疫学会総会抄録集 (ISSN:18803296)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- pp.160, 2008 (Released:2008-10-06)

【目的】我々は、新規多発性筋炎(PM)モデルマウスであるC蛋白誘導筋炎(CIM)を確立し、IL-1欠損マウスでは筋炎の発症が抑制されることを示した。そこで、IL-1がPMの治療標的分子として有用であることを検討する。【方法】組換えヒト骨格筋C蛋白フラグメントをC57BL/6マウスに1回免疫し、CIMを誘導した。CIM筋肉中におけるIL-1の発現をリアルタイムPCR法と免疫染色法により検討した。IL-1レセプターアンタゴニスト (IL-1Ra)及び抗IL-1レセプター抗体 (IL-1RAb)で筋炎に対する治療効果を検討した。CIMマウスリンパ球のフラグメントに対する反応性を、フラグメントをパルスした抗原提示細胞で刺激した時の3Hサイミジン取り込みを測定して検討した。【結果】IL-1は免疫して7日目の発症早期からCIM筋肉中で発現が認められた。IL-1Raを免疫と同時に投与したところ、発症抑制効果を認めた。免疫して7日目からIL-1Ra及びIL-1RAbを投与したところ、両者とも用量依存性に組織学的スコアの改善を認めた。IL-1RAbのほうが、より少ない投与量、投与回数で治療効果を得られた。その治療効果の機序についてT細胞の増殖反応を検討したところ、抗原特異的T細胞のプライミングの阻害ではなかった。【結論】今後、IL-1を標的とした治療はPMの新規治療法として期待される。

- 著者

- 市川 玲子 鈴木 美穂 秋冨 穣

- 雑誌

- 日本心理学会第87回大会

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 2023-08-03

1 0 0 0 投下実験により判明した季節によるオニグルミの割れやすさの違い

- 著者

- 鈴木 美穂 斎藤 亜緒衣 三上 修

- 出版者

- 日本鳥学会

- 雑誌

- 日本鳥学会誌 (ISSN:0913400X)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.71, no.2, pp.179-184, 2022-10-24 (Released:2022-10-31)

- 参考文献数

- 18

ハシボソガラスCorvus coroneは,オニグルミの内部の可食部を食べるために,落とすか,車に轢かせて割る行動をとる.どちらの行動をとるかの意思決定において,クルミの割れやすさは重要な要素だろう.これまでクルミの割れやすさを調べた実験はあったが,10月に実施されたものであった.本研究では,10月と12月にクルミの投下実験を行い割れやすさを比較した.その結果,12月のほうが割れやすいことが明らかになった.

1 0 0 0 OA メカニカルセパレータを用いたヘパリン血漿採血管の性能評価

- 著者

- 鈴木 美穂 菊田 まりな 小笠原 知恵 杉山 大輔 蜂須賀 靖宏 濱口 幸司 岡田 元 大澤 幸雄

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 日本臨床衛生検査技師会

- 雑誌

- 医学検査 (ISSN:09158669)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.67, no.1, pp.29-36, 2018-01-25 (Released:2018-01-27)

- 参考文献数

- 4

ゲル分離剤の代わりに新たな技術であるメカニカルセパレータを用いたヘパリン血漿分離用採血管BDバキュティナ®バリコアTM採血管の検討を行った。バリコアの特長は遠心分離時間が最短で4,000 G・3分間であること,血球と血漿の分離能に優れており,従来のゲル入り血漿分離用採血管に比べて保存安定性が改善されていることである。高速凝固管にて採血した血清を基準とし,従来品のゲル分離剤入りヘパリン採血管ならびにバリコアを比較した。血清と血漿2種の測定値の差は診断・治療に支障のない程度であった。保存安定性において血清よりも血漿が劣る項目はALP,中性脂肪であった。カリウム,LDは従来のヘパリン血漿採血管は不安定であったが,バリコアでは血清と同等の安定性であった。日常業務において,フィブリン析出は報告遅延やサンプリング不良に繋がるリスク要因の一つである。遠心時間の短縮とフィブリン析出問題を解消できるバリコアはTAT短縮や業務軽減に繋がる製品であると考える。

1 0 0 0 OA 日本語節内かき混ぜ文の痕跡位置周辺における処理過程の検討

- 著者

- 柴田 寛 杉山 磨哉 鈴木 美穂 金 情浩 行場 次朗 小泉 政利

- 出版者

- 日本認知科学会

- 雑誌

- 認知科学 (ISSN:13417924)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.13, no.3, pp.301-315, 2006 (Released:2008-11-13)

- 参考文献数

- 34

According to a widely held view, the object-subject-verb word order in Japanese is derived from the subject-object-verb word order by shifting the object to the sentence-initial position. This movement of the object, called scrambling, is hypothesized to leave “a trace” in the original object position (Saito, 1985). With regard to this view, during online sentence processing, a fronted object must be associated with its trace (filler-driven parsing). If a human actually processes scrambled sentences by filler-driven parsing, it is assumed that an object is reactivated and the processing load increases at the trace position. Although many psycholinguistic studies have been conducted in order to investigate the processing of a trace at the trace position, few studies have focused on processing around the trace positions. In the present study, by using a cross-modal lexical priming (CMLP) task that is capable of measuring the processing load and the activation level of an object at arbitrary positions, we investigated the processing around the trace positions in Japanese clause-internal scrambled sentences. In this study, in order to correct the problem encountered in the preceding study (Nakano et al., 2002) using the CMLP task, we did not measure the direct priming effect; however, we measured the indirect priming effect as a method of investigating the activation level of an object. When the data of all the participants were analyzed together, the increases in the processing load and the reactivation of an object around the trace position were not revealed. However, because of the difficulty of the CMLP task, the previous study (Nakano et al., 2002) presented the reactivation of an object at the trace position for participants who responded to lexical decisions quickly and possessed a high working memory capacity. Therefore, the participants in this study were divided into fast and slow groups based on their lexical decision latencies during the task. The results that reflect the filler-driven parsing were revealed only for the fast group. In the fast group, the processing load at the trace position was found to exceed the load at the position preceding and following the trace position. Further analyses of the results showed that the activation level of an object increased only at the trace position.

1 0 0 0 OA 大学初年次生への読書指導法の探究 ―会話の分析を中心に―

- 著者

- 篠崎 祐介 鈴木 美穂 冨士池 優美 北原 博雄 中田 幸司

- 出版者

- 日本リメディアル教育学会

- 雑誌

- リメディアル教育研究 (ISSN:18810470)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- pp.2021.07.20.03, (Released:2021-09-01)

- 参考文献数

- 11

主体的・対話的に批評を行わせる学修活動を取り入れた授業実践を実施し,批評文の変化を分析するとともに,批評文の変化が大きかったグループの学修活動の分析を会話を中心に行った。その結果,取り出した情報と解釈を結びつける理由づけが記述される等の批評文の変化が見られた。また,分析対象となったグループでは,散発的で単調な会話から相手の発言に関連づいた会話に展開していた。作品がただ面白いという感想から,作品の内容や表現に着目しつつ,他者にも捉えられる理由を求めようとする意識が共有されるようになっていった。一方で,批評においてどのような理由を持ち出すとよいのかという点をメタ的・批判的に意識化させることができなかったという実践上の課題が見出された。

1 0 0 0 地産地消講座の実践と消費者の意識変化

- 著者

- 鈴木 美穂子

- 出版者

- 関東東山東海農業経営研究会

- 雑誌

- 関東東海農業経営研究 (ISSN:13423118)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.101, pp.51-55, 2011-02

神奈川県では、新鮮で安全・安心な食料等の供給と農業の有する多面的機能の発揮により、都市農業を持続的に発展させ、県民の健康で豊かな生活の確保を図るため、都市農業推進条例を平成18年4月1日より施行し、この条例に基づいた地産地消推進施策が行われている。神奈川県農業技術センターでは、都市農業の有利性を活かした販売促進手法として、地産地消に関心の高い消費者層を対象としたグループインタビューやホームユーステストを実施し、消費者ニーズの把握や商品化のための情報抽出を行っている。この調査対象者に野菜ソムリエ有資格者がおり、調査後に継続して情報交換する中で、県産農産物の積極的な利用と地域農業の情報発信に積極的な姿勢が確認された。そこで本報告では、地産地消に関心の高い消費者として、神奈川県内の野菜ソムリエの団体「野菜ソムリエコミュニティかながわ」を取り上げ、この団体が開催した消費者向けのセミナーを通じて県農業の情報を提供することにより、講座に参加した消費者の地産地消への関心や青果物の購買行動等へ与える影響を明らかにし、都市農業において県民と協働で進める地産地消の関心促進方策の可能性を検討した。

1 0 0 0 ウイルス的戦略を用いた生体高分子の適応設計

1.進化分子工学において、ウイルス粒子は、遺伝子型と表現型が一つの結合体になっているので、表現型の評価が即遺伝子型の選択に結びつくため、クローニング操作なしに人為淘汰が行える。これを模擬する試験管無いプロセスとして、無細胞翻訳系でmRNAと新生タンパク分子が結合体となるような系(これを以下in vitroウイルスと呼ぶ)を開発しつつある。in vitroウイルスは、逆転写、PCR増幅、転写という、レトロウイルス様のライフサイクルで増殖する。mRNAと新生蛋白の結合法として、2つの方法を試みた。一つは、その蛋白に組み込まれたビオチン様ペプチドと、mRNAに付加されたアビジンとの結合による。もう一つは、mRNAをtRNAとみなすことができるように改変する方法である。このmRNAの3'末端CCAにシンテターゼを用いて、アミノ酸をチャージする事には成功した。2.進化分子工学は生命の起源のモデルと表裏一体をなす。われわれは、進化分子工学において、遺伝子型と表現型を対応づける戦略としてのウイルス型戦略が、細胞型戦略よりも進化速度の点で有利であることに着目した。RNAワールドから、蛋白質合成系が進化してくる機構として、in vitroウイルス様の生命体があったとするモデルを構築することに成功した。すなわち、RNAワールドに登場する最初のコード化された蛋白質はRNAレプリカーゼ(当然リボザイムである)の補因子に違いないが、その蛋白質補因子はそれがコードされているリボザイムRNAに結合していたとする。すると、RNA複製系と翻訳系が、速やかに安定に漸進的に共進化してくることが、コンピュータシミュレーションで明らかにされた。それは、ウイルス型メンバーを持つハイパーサイクルである。

1 0 0 0 OA 訪問介護サービスを利用する高齢者のコンビニエンスストア利用の実態

- 著者

- 五十嵐 歩 松本 博成 鈴木 美穂 濵田 貴之 青木 伸吾 油山 敬子 村田 聡 鈴木 守 安井 英人 山本 則子

- 出版者

- 日本老年社会科学会

- 雑誌

- 老年社会科学 (ISSN:03882446)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.40, no.3, pp.283-291, 2018-10-20 (Released:2019-11-15)

- 参考文献数

- 7

本研究は,訪問介護を利用する在宅高齢者におけるコンビニ利用の実態を把握することを目的とした.東京都A区において調査協力への同意が得られた訪問介護事業所および小規模多機能型居宅介護事業所の管理者(n = 28)を対象とし,コンビニが生活支援の役割を果たしている利用者の事例に関して,利用者特性やコンビニの利用状況を問う質問紙への回答を依頼した.対象事業所より64事例について回答があった.事例の利用者は,平均年齢77.8±11.4歳,男性30人(47%)であり,要介護1(31%)と要介護2(30%)が多かった.1人で来店する者が68%であり,徒歩での来店が75%を占め,購入品は弁当・パン・惣菜がもっとも多かった(91%).ADL障害のある者はない者と比較して,サービス提供者の同行が多く(p = 0.001),車いす等徒歩以外の来店割合が高かった(p = 0.018).サービス提供者は,日中1人で過ごす者(p = 0.064)とADL障害がある者(p = 0.013)に対して,コンビニの存在をより重要と評価していた.

1 0 0 0 OA Go言語を使ったGAEアプリケーションの開発

- 著者

- 石井涼 鈴木美穂 大谷真

- 雑誌

- 第74回全国大会講演論文集

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.2012, no.1, pp.499-500, 2012-03-06

2011年5月に発表されたGoogleAppEngine1.5.0において、実験的ではあるが、新たにプログラミング言語「Go」のサポートが始まった。既に対応しているPythonとJavaに比べてどのようなメリットやデメリットがあるのかをGo言語自体の評価も含めて、ブログアプリケーション開発を通じて研究した。

1 0 0 0 OA マイクロフルイディックエンジニアリングの深化と生体分子高感度定量計測への展開

- 著者

- 庄子 習一 竹山 春子 水野 潤 関口 哲志 細川 正人 尹 棟鉉 鈴木 美穂 福田 武司 船津 高志 武田 直也 モリ テツシ 枝川 義邦

- 出版者

- 早稲田大学

- 雑誌

- 基盤研究(S)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- 2011-04-01

本研究では、微小発光サンプルの光学的超高感度定量計測を可能とすべく、以下の新規マイクロ流体デバイス要素技術を開発した。1)自由なサイズの液滴作製技術の構築,2) 自由な流れのコントロール技術の構築,3) 液滴のパッシブソーティング技術の構築。次に要素技術をシステム化することにより、微小発光サンプルの計測を実現した。1)液滴に生体サンプルを個別に抱合して環境微生物個々の遺伝子を解析,2) 個別に抱合された細胞の成長を観察して酵素反応活性を評価。本研究の遂行により、従来定性的観察のみ可能であった光学信号が高感度な定量的計測結果を得るのに十分なレベルに増幅され、光学的定量計測が実現された。