2 0 0 0 OA 吉田知子・初期作品の世界(一) : 『無明長夜』の周辺

- 著者

- 田中 裕之

- 出版者

- 梅花女子大学文化表現学部

- 雑誌

- 梅花女子大学文化表現学部紀要 = Baika Women's University Faculty of Cultural and Expression Studies Bulletin (ISSN:24320420)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- no.17, pp.79-87, 2021-03-20

2 0 0 0 OA 日本版敗血症診療ガイドライン2020

- 著者

- 江⽊ 盛時 ⼩倉 裕司 ⽮⽥部 智昭 安宅 ⼀晃 井上 茂亮 射場 敏明 垣花 泰之 川崎 達也 久志本 成樹 ⿊⽥ 泰弘 ⼩⾕ 穣治 志⾺ 伸朗 ⾕⼝ 巧 鶴⽥ 良介 ⼟井 研⼈ ⼟井 松幸 中⽥ 孝明 中根 正樹 藤島 清太郎 細川 直登 升⽥ 好樹 松嶋 ⿇⼦ 松⽥ 直之 ⼭川 ⼀⾺ 原 嘉孝 ⼤下 慎⼀郎 ⻘⽊ 善孝 稲⽥ ⿇⾐ 梅村 穣 河合 佑亮 近藤 豊 斎藤 浩輝 櫻⾕ 正明 對東 俊介 武⽥ 親宗 寺⼭ 毅郎 東平 ⽇出夫 橋本 英樹 林⽥ 敬 ⼀⼆三 亨 廣瀬 智也 福⽥ ⿓将 藤井 智⼦ 三浦 慎也 安⽥ 英⼈ 阿部 智⼀ 安藤 幸吉 飯⽥ 有輝 ⽯原 唯史 井⼿ 健太郎 伊藤 健太 伊藤 雄介 稲⽥ 雄 宇都宮 明美 卯野⽊ 健 遠藤 功⼆ ⼤内 玲 尾崎 将之 ⼩野 聡 桂 守弘 川⼝ 敦 川村 雄介 ⼯藤 ⼤介 久保 健児 倉橋 清泰 櫻本 秀明 下⼭ 哲 鈴⽊ 武志 関根 秀介 関野 元裕 ⾼橋 希 ⾼橋 世 ⾼橋 弘 ⽥上 隆 ⽥島 吾郎 巽 博⾂ ⾕ 昌憲 ⼟⾕ ⾶⿃ 堤 悠介 内藤 貴基 ⻑江 正晴 ⻑澤 俊郎 中村 謙介 ⻄村 哲郎 布宮 伸 則末 泰博 橋本 悟 ⻑⾕川 ⼤祐 畠⼭ 淳司 原 直⼰ 東別府 直紀 古島 夏奈 古薗 弘隆 松⽯ 雄⼆朗 松⼭ 匡 峰松 佑輔 宮下 亮⼀ 宮武 祐⼠ 森安 恵実 ⼭⽥ 亨 ⼭⽥ 博之 ⼭元 良 吉⽥ 健史 吉⽥ 悠平 吉村 旬平 四本 ⻯⼀ ⽶倉 寛 和⽥ 剛志 渡邉 栄三 ⻘⽊ 誠 浅井 英樹 安部 隆国 五⼗嵐 豊 井⼝ 直也 ⽯川 雅⺒ ⽯丸 剛 磯川 修太郎 板倉 隆太 今⻑⾕ 尚史 井村 春樹 ⼊野⽥ 崇 上原 健司 ⽣塩 典敬 梅垣 岳志 江川 裕⼦ 榎本 有希 太⽥ 浩平 ⼤地 嘉史 ⼤野 孝則 ⼤邉 寛幸 岡 和幸 岡⽥ 信⻑ 岡⽥ 遥平 岡野 弘 岡本 潤 奥⽥ 拓史 ⼩倉 崇以 ⼩野寺 悠 ⼩⼭ 雄太 ⾙沼 関志 加古 英介 柏浦 正広 加藤 弘美 ⾦⾕ 明浩 ⾦⼦ 唯 ⾦畑 圭太 狩野 謙⼀ 河野 浩幸 菊⾕ 知也 菊地 ⻫ 城⼾ 崇裕 ⽊村 翔 ⼩網 博之 ⼩橋 ⼤輔 ⿑⽊ 巌 堺 正仁 坂本 彩⾹ 佐藤 哲哉 志賀 康浩 下⼾ 学 下⼭ 伸哉 庄古 知久 菅原 陽 杉⽥ 篤紀 鈴⽊ 聡 鈴⽊ 祐⼆ 壽原 朋宏 其⽥ 健司 ⾼⽒ 修平 ⾼島 光平 ⾼橋 ⽣ ⾼橋 洋⼦ ⽵下 淳 ⽥中 裕記 丹保 亜希仁 ⾓⼭ 泰⼀朗 鉄原 健⼀ 徳永 健太郎 富岡 義裕 冨⽥ 健太朗 富永 直樹 豊﨑 光信 豊⽥ 幸樹年 内藤 宏道 永⽥ 功 ⻑⾨ 直 中村 嘉 中森 裕毅 名原 功 奈良場 啓 成⽥ 知⼤ ⻄岡 典宏 ⻄村 朋也 ⻄⼭ 慶 野村 智久 芳賀 ⼤樹 萩原 祥弘 橋本 克彦 旗智 武志 浜崎 俊明 林 拓也 林 実 速⽔ 宏樹 原⼝ 剛 平野 洋平 藤井 遼 藤⽥ 基 藤村 直幸 舩越 拓 堀⼝ 真仁 牧 盾 增永 直久 松村 洋輔 真⼸ 卓也 南 啓介 宮崎 裕也 宮本 和幸 村⽥ 哲平 柳井 真知 ⽮野 隆郎 ⼭⽥ 浩平 ⼭⽥ 直樹 ⼭本 朋納 吉廣 尚⼤ ⽥中 裕 ⻄⽥ 修

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 日本集中治療医学会

- 雑誌

- 日本集中治療医学会雑誌 (ISSN:13407988)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- pp.27S0001, (Released:2020-09-28)

- 被引用文献数

- 2

日本集中治療医学会と日本救急医学会は,合同の特別委員会を組織し,2016年に発表した日本版敗血症診療ガイドライン(J-SSCG2016)の改訂を行った。本ガイドライン(J-SSCG2020)の目的は,J-SSCG2016と同様に,敗血症・敗血症性ショックの診療において,医療従事者が患者の予後改善のために適切な判断を下す支援を行うことである。改訂に際し,一般臨床家だけでなく多職種医療者にも理解しやすく,かつ質の高いガイドラインとすることによって,広い普及を目指した。J-SSCG2016ではSSCG2016にない新しい領域(ICU-acquiredweakness(ICU-AW)とPost-Intensive Care Syndrome(PICS),体温管理など)を取り上げたが,J-SSCG2020では新たに注目すべき4領域(Patient-and Family-Centered Care,Sepsis Treatment System,神経集中治療,ストレス潰瘍)を追加し,計22 領域とした。重要な117の臨床課題(クリニカルクエスチョン:CQ)をエビデンスの有無にかかわらず抽出した。これらのCQには,日本国内で特に注目されているCQも含まれる。多領域にわたる大規模ガイドラインであることから,委員24名を中心に,多職種(看護師,理学療法士,臨床工学技士,薬剤師)および患者経験者も含めたワーキンググループメンバー,両学会の公募によるシステマティックレビューメンバーによる総勢226名の参加・協力を得た。また,中立的な立場で横断的に活躍するアカデミックガイドライン推進班を2016年版に引き続き組織した。将来への橋渡しとなることを企図して,多くの若手医師をシステマティックレビューチーム・ワーキンググループに登用し,学会や施設の垣根を越えたネットワーク構築も進めた。作成工程においては,質の担保と作業過程の透明化を図るために様々な工夫を行い,パブリックコメント募集は計2回行った。推奨作成にはGRADE方式を取り入れ,修正Delphi法を用いて全委員の投票により推奨を決定した。結果,117CQに対する回答として,79個のGRADEによる推奨,5個のGPS(Good Practice Statement),18個のエキスパートコンセンサス,27個のBQ(Background Question)の解説,および敗血症の定義と診断を示した。新たな試みとして,CQごとに診療フローなど時間軸に沿った視覚的情報を取り入れた。J-SSCG2020は,多職種が関わる国内外の敗血症診療の現場において,ベッドサイドで役立つガイドラインとして広く活用されることが期待される。なお,本ガイドラインは,日本集中治療医学会と日本救急医学会の両機関誌のガイドライン増刊号として同時掲載するものである。

2 0 0 0 特異的言語発達障害の言語学的分析 : 研究者の立場から

- 著者

- 田中 裕美子

- 出版者

- The Japan Society of Logopedics and Phoniatrics

- 雑誌

- 音声言語医学 (ISSN:00302813)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.44, no.3, pp.216-221, 2003-07-20

- 参考文献数

- 20

- 被引用文献数

- 3 1

英語圏の特異的言語発達障害 (SLI) は文法形態素獲得の遅れを主症状とする文法障害である.5歳での発現率は7.4%で, 言語障害は青年期まで長期化する.SLI研究法は, 理論をデータから検証するトップダウン方式が中心であり, 異言語間比較が理論追求に寄与するところが大きい.本研究では, 幼稚園でのスクリーニングにより同定したSLI群, 健常群, 知的障害児群とで, 語順や名詞数という言語学的要因を変化させた文理解成績を比較した.その結果, SLI群では健常の言語年齢比較群や知的障害群とは異なる反応パタンが見られ, 言語情報処理能力の欠陥説を支持した.さらに, 臨床家にSLIと診断された3症例に文理解や音韻記憶課題を実施した結果, SLIの評価・診断法としての有用性が示唆された.言語発達の遅れを「ことばを話すか」という現象のみで捉えるのでなく, 「何をどのように話すか」といった言語学的視点などを含め多面的で掘り下げ的な評価法の確立が今後期待される.

2 0 0 0 OA 小児包茎の治療方針と手術適応

- 著者

- 伊藤 泰雄 韮澤 融司 薩摩林 恭子 田中 裕之 長谷川 景子 関 信夫

- 出版者

- Japan Surgical Association

- 雑誌

- 日本臨床外科医学会雑誌 (ISSN:03869776)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.54, no.3, pp.631-635, 1993-03-25 (Released:2009-01-22)

- 参考文献数

- 9

われわれは,小児包茎に対しできるだけ用手的に包皮翻転を行い,手術は必要最小限としている.昭和61年以降,包茎を主訴に当科を受診した527例を対象に,包茎の形態を分類し,病型別に治療成績を検討した.病型の明らかな427例の内訳はI型(短小埋没陰茎)22例, II型(トックリ型)86例, III型(ピンホール型)60例, IV型(中度狭窄型)154例, V型(軽度狭窄型) 101例, VI型(癩痕狭窄型) 4例であった.その結果,翻転不能例はI型の13例, 59.1%, II型の17例, 19.8%, VI型の2例, 50.0%のみであった.ピンホール型は一見高度の狭窄に見えるが,翻転不能例は1例もなかった.最終的に手術を行ったのは全症例中32例, 6.1%と少なかった.外来で積極的に包皮を翻転するわれわれの治療方針は,包茎手術を著しく減少させた.

2 0 0 0 OA 野本将軍塚古墳と東国の前期古墳

2 0 0 0 慢性関節リウマチに対する高濃度炭酸ガス浴の効果

- 著者

- 前田 真治 山北 秀香 佐々木 麗 田中 裕美子 後出 秀聡 木村 広 井上 市郎

- 出版者

- The Japanese Society of Balneology, Climatology and Physical Medicine

- 雑誌

- 日本温泉気候物理医学会雑誌 (ISSN:00290343)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.61, no.4, pp.187-194, 1998-08-01

- 参考文献数

- 13

- 被引用文献数

- 1

慢性関節リウマチ (RA) 患者を対象に組織循環改善作用と新陳代謝亢進による疼痛の軽減を目的に90%以上になる高濃度炭酸ガス浴装置を用い効果を調べた。<br>気体としての炭酸ガス浴は更衣動作の障害されているRA患者にとって, 衣服のまま入浴できる画期的な入浴法である。血圧・脈拍の大きな変化なく, 循環機能の影響の少ない入浴法と考えられた。表面皮膚温も前値に比べ入浴後期に1℃以上の上昇がみられ, 局所の血液循環の改善が示唆され, 老廃物・疼痛物質などの除去・新陳代謝改善の効果が期待できると考えられた。ADL得点 (平均67→75/96), Visual Analogue Pain Scale (5.3→2.7/10), Face Scale (9.4→5.4/20), AIMS変法 (身体的要素28.5→30.1, 社会的25.2→27.3, 精神的26.2→29.9/36) と入浴前に比べ有意に改善しており, 高濃度炭酸ガス浴がRA患者のADL・QOLの改善に効果があると思われた。

2 0 0 0 IR 『琵琶伝』に見る鏡花の恋愛至上主義 : 婚姻制度に対する問題提起

『琵琶伝』は泉鏡花により,尾崎紅葉の『やまと昭君』を先行作品としてかかれた小説である。二年前に『琵琶伝』を扱い「夢・幻想」の観点から鸚鵡の登場による効果を考察し、『琵琶伝』は「観念小説」ではなく「幻想小説」であることを論じようと試みた。今回はその逆で『琵琶伝』は「幻想小説」ではないという論を進めていきたいと思う。「大衆と国家」や「家族と親族」などの観点から、社会の状況、婚姻制度や鏡花の恋愛・結婚観について見ていくことを通して『琵琶伝』における主題とは一体何であるのかを考察したい。

2 0 0 0 OA 簡易懸濁法に関わる情報提供の迅速化と適正化を支援する データベースの構築

- 著者

- 渡邊 政博 田井 達也 辻 繁子 田中 裕章 元木 貴大 山口 佳津騎 住吉 健太 野崎 孝徒 加地 雅人 朝倉 正登 小坂 信二 芳地 一

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人日本医薬品情報学会

- 雑誌

- 医薬品情報学 (ISSN:13451464)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.17, no.2, pp.69-76, 2015 (Released:2015-10-01)

- 参考文献数

- 22

Objective: Many patients in Kagawa University Hospital are administered medicines prepared by the simple suspension method. Pharmacists in charge of these patients receive inquiries from doctors and nurses regarding the suitability of medicines for the simple suspension method. Answering these inquiries is complicated and time-consuming as multiple data sources need to be searched. In order to simplify these complicated procedures, we herein attempted to develop a novel database to provide valuable information that could contribute to the safe performance of the simple suspension method, and evaluated its usefulness.Method: The specifications of the database were determined by analyzing previously answered inquiries. To evaluate the usefulness of the database, we used test prescriptions and compared the amount of time required to gather information using the database and the conventional method, i.e., using books alone. We also analyzed previous prescriptions with the database in order to determine what kinds of problems could be detected.Results: The investigation of previous prescriptions indicated that some medicines needed to be examined not only for their suitability for the simple suspension method, but also their incompatibility. Therefore, we added a feature regarding the incompatibility of medicines to the database. The time required to gather the information needed to answer the test prescription was shorter with our database than with the conventional method. Furthermore, the database improved the detection of medicines that require particular attention for their properties including incompatibility. An analysis of previous prescriptions using our database indicated the possibility of incompatibility in half of the previous prescriptions examined.Conclusion: Our database could rapidly provide information related to the simple suspension method, including the incompatibility of medicines.

2 0 0 0 OA 好奇心と物欲の系譜-教養文化とは何であったか?

本研究プロジェクトでは,「消費文化史研究会」開催を通じて,この新領域に関する共通認識を培いつつ,構成員をそれぞれ単独執筆者とする著作シリーズ発刊の準備を進めてきた.成果の一部は, 2009年社会経済史学会のパネル報告「消費社会における教養を考える」で公表された.また, 2011年度末に開催された国際シンポジウムでは,国内外の研究者25名の講演・発表を通じて,研究成果を集約するとともに,今後の学問的課題を確認した.

2 0 0 0 概念レベルにおける電子化辞書の情報構造

- 著者

- 横井 俊夫 仲尾 由雄 荻野 孝野 田中 裕一

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人情報処理学会

- 雑誌

- 情報処理学会論文誌 (ISSN:18827764)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.38, no.1, pp.32-43, 1997-01-15

- 被引用文献数

- 8

大規模な電子化辞書(その情報内容である言語知識)が概念レベルで持つべき情報構造を明らかにする.ここでいう電子化辞書とは 通常の辞書ばかりではなく シソーラス コーパス テキストベースなどを含む統合的な言語情報(言語知識)のことである.概念レベルは意味を扱う深層レベルの中で基準となる役割を果たす.表層レベルに最も近く それに沿う情報構造を持つ.なお この情報構造はEDR電子化辞書の成果を再整理することにより得られたものである.実現事例としてEDR電子化辞書の概念対応部分を仕様と統計データの両面から説明する.大規模知識ベースなどの議論に見られるように 大規模な情報や知識の構造を解明していく研究の重要性が指摘され始めている.本稿の内容は 本格的な実現事例を持つ初めての試みとなっている.This paper describes a model of the information structure of large-scale electronic dictionaries at the concept level that contain wide-ranging linguistic knowledge. The term electronic dictionary in this paper means an integrated body of linguistic information and knowledge that includes the information provided by thesauri, tagged corpora, and raw corpora as well as ordinary dictionaries. The concept level plays an important role for deep levels containing the information of semantic processing. It is the nearest to the surface level and its structure is similar. This information structure is obtained by rearranging the structure of the EDR Electronic Dictionary. An example of actual realization of the information structure is described in view of both the specifications and numeristic data of the EDR Dictionary at the concept level. Recently, the importance of the research on the structure of large-scale information and knowledge has become a focus of interest, as shown in the discussions for large-scale knowledge bases, etc. This paper introduces the results of the first trial including full-scale example of actual realization.

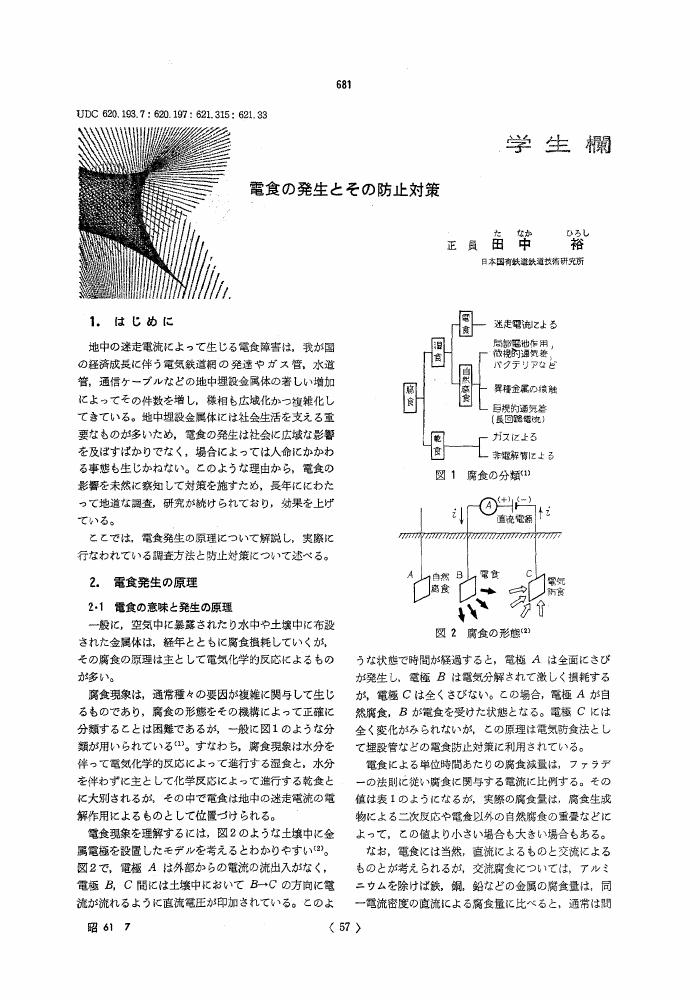

1 0 0 0 OA 電食の発生とその防止対策

- 著者

- 田中 裕

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 電気学会

- 雑誌

- 電氣學會雜誌 (ISSN:00202878)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.106, no.7, pp.681-684, 1986-07-20 (Released:2008-04-17)

- 参考文献数

- 3

1 0 0 0 OA 侵襲時の補体活性化からみた多臓器不全の病態解明に関する研究

多臓器不全は大きな侵襲や重篤な感染症が契機となることが多く、治療に難渋しその死亡率も未だ高い。生体侵襲時には補体活性化が生じ、TMAが引き起こされる。TMAは全身臓器の微小血管の血栓形成と、血管内皮細胞障害を呈する。しかし生体侵襲時の補体活性化による多臓器不全の機序については明らかでない。本研究目的は侵襲時の多臓器不全の病態を補体活性化によるTMAという新たなる視点から解明することである。侵襲時における、(1)補体活性の定量評価、(2)TMAとの関連、(3)補体活性化と白血球・血小板連関、(4)補体活性の制御による多臓器不全抑制の検討を行う。

1 0 0 0 OA 早期に再発した十二指腸未分化多形肉腫の1例

- 著者

- 田中 裕也 坂本 龍之介 矢野 由香 佐野 史歩 井口 智浩 久我 貴之

- 出版者

- 日本臨床外科学会

- 雑誌

- 日本臨床外科学会雑誌 (ISSN:13452843)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.80, no.9, pp.1652-1657, 2019 (Released:2020-03-31)

- 参考文献数

- 16

- 被引用文献数

- 1 1

症例は69歳,男性.心窩部痛と食欲不振を主訴に受診.上部消化管内視鏡検査で十二指腸下行脚に全周性の隆起性病変を認め,生検にて未分化多形肉腫と診断された.明らかな遠隔転移はなく,亜全胃温存膵頭十二指腸切除術を施行した.術後2.5カ月で施行したCT検査にて,肝転移と局所再発を指摘された.Doxorubicin投与を開始したが,病状が悪化し術後5.5カ月で永眠した.未分化多形肉腫の好発部位は四肢や後腹膜であり,十二指腸原発の報告例はこれまでに6例のみである.文献的考察を加えて報告する.

- 著者

- 三谷 英範 望月 俊明 大谷 典生 三上 哲 田中 裕之 今野 健一郎 石松 伸一

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 日本救急医学会

- 雑誌

- 日本救急医学会雑誌 (ISSN:0915924X)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.25, no.11, pp.833-838, 2014-11-15 (Released:2015-03-12)

- 参考文献数

- 9

- 被引用文献数

- 1

はじめに:尿素サイクル異常症であるornithine transcarbamylase(OTC)欠損症の頻度は日本で14,000人に1人とされ,18歳以降での発症例は稀であるが,発症すると重症化しうる疾患である。我々は,19歳発症のOTC欠損症により高アンモニア血症・痙攣重積発作を来し,救命し得なかった1例を経験した。症例:19歳の男性。来院前日,嘔吐・下痢・全身倦怠感を主訴に救急要請した。前医に搬送され,血液検査や頭部CTでは異常を認めないものの,全身倦怠感が強く入院加療を行うこととなった。入院後,不穏状態に続いて強直性痙攣が出現した。ジアゼパム静注で痙攣は消失したが,その後意識レベル改善なく当院へ紹介転院となった。当院来院時,頭部CTで全般性に浮腫性変化認め,血中アンモニア濃度は500µg/dL以上であった。当院入院後,痙攣再燃したため鎮静薬・抗てんかん薬を増量しつつ管理するも,痙攣は出現と消失を繰り返した。血中アンモニア濃度は低下傾向であったため透析の導入は見送った。第2病日に瞳孔散大,第4病日に脳波はほぼ平坦となり,脳幹反射は消失した。その後も高アンモニア血症は持続し,代謝異常による痙攣も疑われたため,各種検査を施行しつつ全身管理に努めたが,第11病日に血圧維持困難となり死亡した。後日,血中・尿中アミノ酸分画やオロト酸の結果からOTC欠損症と診断された。考察:尿素サイクル異常症は稀であるが,高アンモニア血症を来している場合には迅速に対応しなければ不可逆的な神経障害を来す。治療には透析が考慮されるが,本症例では痙攣が軽減した後血中アンモニア濃度は低下傾向であったため透析は施行しなかった。結語:血糖正常,アニオンギャップ正常の高アンモニア血症では尿素サイクル異常症を鑑別に挙げ,透析を早期に検討する必要がある。

- 著者

- 松岡 友実 五十嵐 公嘉 齋藤 智之 高田 希望 橋本 玲奈 一條 聖美 小林 悠 田中 裕也 川本 俊輔 宮里 紘太 秋谷 友里恵 小林 洋輝 堀越 周 馬場 晴志郎 高島 弘至 逸見 聖一朗 功力 未夢 岡本 裕美 阿部 雅紀

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 日本透析医学会

- 雑誌

- 日本透析医学会雑誌 (ISSN:13403451)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.56, no.1, pp.1-6, 2023 (Released:2023-01-28)

- 参考文献数

- 8

新型コロナウイルス感染症(COVID-19)において透析患者は重症化リスクが高く,COVID-19流行初期は,原則として全例入院加療で対応していた.しかし,東京都においては受け入れ可能な入院施設は限定され,新規陽性患者数の急増により,入院調整が困難な状況に陥っていた.そのため,東京都は2021年12月中旬に透析患者の受け入れが可能なCOVID-19透析患者の収容施設として,旧赤羽中央総合病院跡地を活用した酸素・医療提供ステーション(東京都酸素ステーション)を開設した.2022年1月1日~8月31日まで,酸素ステーションで受け入れたCOVID-19透析患者の現況を報告する.入所患者は211人,平均年齢は65歳,転帰は,自宅退院194例(92%),転院16例(7.5%)(そのうち肺炎の疑い13例(6.1%)),死亡1例(0.5%)であった.当施設は東京都のCOVID-19透析患者の入院待機者数の減少および病床ひっ迫の緩和の機能を果たし,また,治療の介入により重症化や入院を予防しており,施設の運用は有効であった.

1 0 0 0 OA アルコールと軽油からなる混合溶液の密度挙動

- 著者

- 加藤 昌弘 村松 輝昭 田中 裕之 森谷 信次 柳沼 福夫 一色 尚次

- 出版者

- The Japan Petroleum Institute

- 雑誌

- 石油学会誌 (ISSN:05824664)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.34, no.2, pp.186-190, 1991-03-01 (Released:2008-10-15)

- 参考文献数

- 3

- 被引用文献数

- 1 2

私達は, 先にアルコール-軽油混合液の沸点挙動について報告した1)。今回, アルコール-軽油混合溶液の液密度について検討した。使用した6種類のアルコールは, メタノール, エタノール, 1-プロパノール, 2-プロパノール, 1-ブタノール, 2-メチル-1-プロパノールである。さらに, 軽油の代表成分としてセタンを選び, メタノール-セタン, エタノール-セタン系についても検討した。密度測定には Anton-Paar 社製のデジタル密度計を用いた。Table 1に使用したアルコール, セタン, 軽油の物性値を示す。Figs. 1~3とTables 2~6に今回298.15Kで得られた密度データを示す。298.15Kにおいてメタノール-軽油, メタノール-セタン, エタノール-軽油, エタノール-セタン系で不均一領域が得られた。Tables 3~6に不均一となった4種の系について得られた密度データを示す。2液相領域では上相, 下相をそれぞれ取り出し密度を測定した。密度データの交点から相互溶解度を求めた。精度は軽油系で約±0.01, セタン系で約±0.001重量分率である。Table 7に今回求めた相互溶解度をそれぞれ示す。次に, メタノールあるいはエタノール10gと軽油10gからなる不均一混合溶液に第三成分として水を加え, 密度挙動を測定した。Tables 8, 9とFigs. 4, 5に測定結果を示す。Figs. 4, 5における実線の交点でアルコール相と軽油相が等密度となる。等密度エマルション混合溶液は相分離に時間がかかり, 自動車用エンジンにほぼ均一な供給が可能になる。

1 0 0 0 OA 日本版敗血症診療ガイドライン2016 CQ8 敗血症性ショックに対するステロイド療法

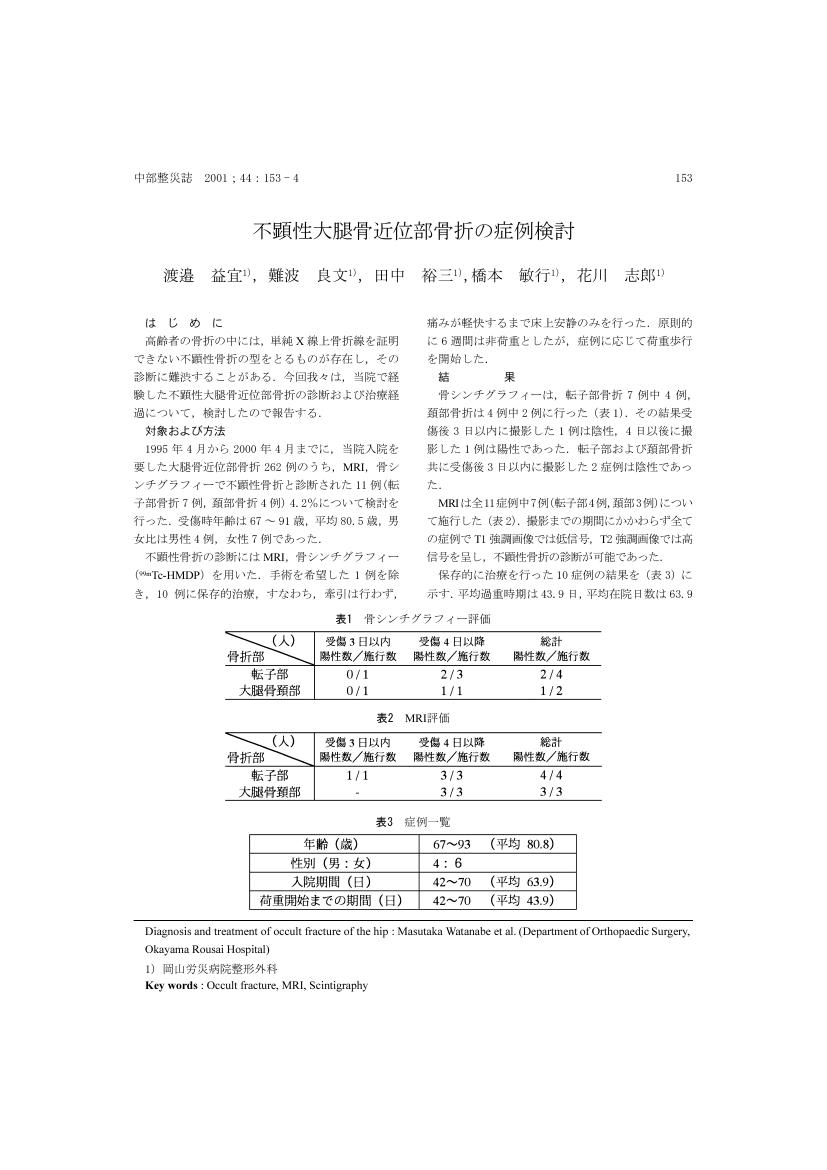

1 0 0 0 不顕性大腿骨近位部骨折の症例検討

- 著者

- 渡邉 益宜 難波 良文 田中 裕三 橋本 敏行 花川 志郎

- 出版者

- 中部日本整形外科災害外科学会

- 雑誌

- 中部日本整形外科災害外科学会雑誌 (ISSN:00089443)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.44, no.1, pp.153-154, 2001 (Released:2001-11-07)

- 参考文献数

- 4

- 被引用文献数

- 1

1 0 0 0 OA 地震時の人体被災度計測手法の開発 ―胸部圧迫実験用ダミーの作製―

- 著者

- 宮野 道雄 生田 英輔 長嶋 文雄 田中 裕 梶原 浩一 奥野 倫子

- 出版者

- 一般社団法人 地域安全学会

- 雑誌

- 地域安全学会論文集 (ISSN:13452088)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.10, pp.49-54, 2008-11-14 (Released:2019-04-18)

- 参考文献数

- 18

The immediate victims of the 1995 Hyogo-ken Nanbu Earthquake included 5,502 dead and 41,527 wounded. The death rate among victims in collapsed buildings was purported to be as high as 90%. However, we have no way to examine how the victim got dead or wounded, except for autopsy and interview with the bereaved. We need knowledge in detail about what part of building or furniture caused casualty and how it was occurred. Therfore, we aimed to make a dummy to measure human body damage due to collapsed buildings or toppled furniture. This dummy will be used in large-scale fracture tests of buildings to evaluate human body damage due to earthquakes.

1 0 0 0 OA 文化の偶像崇拝 : マシュー・アーノルドの批評体系(関東英文学研究)

- 著者

- 田中 裕介

- 出版者

- 一般財団法人 日本英文学会

- 雑誌

- 英文学研究 支部統合号 (ISSN:18837115)

- 巻号頁・発行日

- vol.1, pp.127-144, 2009-01-10 (Released:2017-06-16)

It seems strange that Matthew Arnold, who could be regarded as a realistic relativist, devoted himself to the belief that 'culture' is an abstract and absolute idea, in his most famous work, Culture and Anarchy. In this paper, I will recount the how (not the why) of his thoughts by examining the transition of his use of critical terms such as 'culture' and 'state.' Through his early prose works, Arnold struggled to abandon the romantic sentiments that overwhelmed him as a young poet and confirm his own view of poetry by idealising the verbal reproduction of the 'actions' described in ancient Greek plays. In On Translating Homer, a creative activity based on 'models' was generalised as a form of recognition 'to see the object as in itself it really is', which he called 'criticism.' In 'Function of Criticism at the Present Time,' he defined 'criticism' as a mediating art to diffuse normative knowledge to a whole society; in his educational reports, he considered 'state' as an 'art' of creating or maintaining national unity. 'State' became a normative idea in Culture and Anarchy, where 'culture' was considered to function as a medium through which the English could attain the ideal. However, in his critical terminology, the word 'culture' has diverse meanings. In his early politico-historical essay, 'Democracy,' there is a strong indication of the general mode of the lives of the English aristocracy. Originally, it was a concrete noun that suggests a particular national life, though it gradually became an abstract concept that referred to general humanity. In 'Function of Criticism at the Present Time,' he stressed the social instrumentality of 'criticism' while restraining himself from pushing 'culture' to the forefront. Prior to Culture and Anarchy, he appeared to hesitate to use the word 'culture' extensively, especially in his literary criticism, since it is a term that implies nationality and is closely associated with romanticism, which he negated in his earlier writings. Thus, how did he manage to employ 'culture' as a normative concept in Culture and Anarchy? Paradoxically, he achieved this by defining it as an art. Based on the parallelism with the concept of the state, it follows the process by which 'state' changes from an instrumental framework to a normative idea. In this work, Arnold not only absolutised but also personalised the term 'culture', which appeared to be a medium or an image of God. Arnold claimed that the English adored 'culture' as it could function as a medium for their intellectual perfection. Absolute diction enabled him to use the word with a kind of transcendent significance. For this reason, we can consider the quasi-religious language of Culture and Anarchy as the discourse of idolatry.